Winthrop Chandler: The First American Painter of American Landscapes

This is an archive article from Antiques & Fine Art magazine.

Winthrop Chandler (1747–1790) is the first known American artist to paint American landscapes that have survived. The artists who painted American landscapes prior to Chandler are either unknown, were not born in America, or if they were, did not paint American scenes.1 An American, Sibyl Huntington May, painted an overmantel with people, animals, and her husband’s church, for his parsonage in Haddam, Connecticut, sometime after its completion in 1758.2 However, she only painted a single work.

Winthrop Chandler was the great-grandson of Deacon John Chandler (1610–1703), one of the founders, in 1686, along with the Gore and the Ruggles families, of Woodstock, Connecticut. His father, Captain William Chandler (1698–1754), was a surveyor and farmer, and his mother, Jemima Bradbury Chandler (1703–1779), was a descendant of Massachusetts Governors Winthrop and Dudley. Winthrop Chandler was born in 1747 on Chandler Hill on the Woodstock and Thompson line in Connecticut. He was the youngest of ten children and seven years old when his father died. At the age of fourteen, he applied to the court for a guardian—required for an apprenticeship—to study painting, and selected his sister Jemima’s husband, Samuel McClellan, of South Woodstock. A history of Worcester states that Chandler studied the art of painting in Boston, but there are no records to indicate where or with whom he studied.3 Nina Fletcher Little proposed that he studied with John Gore, a portrait painter in Boston, since the Gores were neighbors of the Chandlers in Woodstock for generations. She also conjectured that he knew John Singleton Copley (1738–1815), who painted Chandler’s first cousin, Lucretia Chandler, in 1763.4 Chandler lived all his life in Woodstock, except for his last five years, which he spent in Worcester, Massachusetts. He married Mary Gleason of Dudley, Massachusetts, in 1772, and they had five sons and two daughters.

Chandler’s two earliest landscapes, done before his apprenticeship, were painted on plaster, circa 1758–1761, in his guardian, Samuel McClellan’s, house (Fig. 1). McClellan bought the house in 1757, and added a new wing, where the landscapes were located. Only one of these landscapes is still visible. It shows an aerial view of houses on the South Woodstock Green. McClellan’s house is the ochre yellow house at the top of the scene. McClellan is depicted in a red coat astride a horse. McClellan served as a lieutenant in the French and Indian War and led his troops in the Battles of Lexington and Concord. To his right, his wife and daughter stand next to a well with a sweep. An 1859 photograph shows the town green with the well and sweep (Fig. 7).

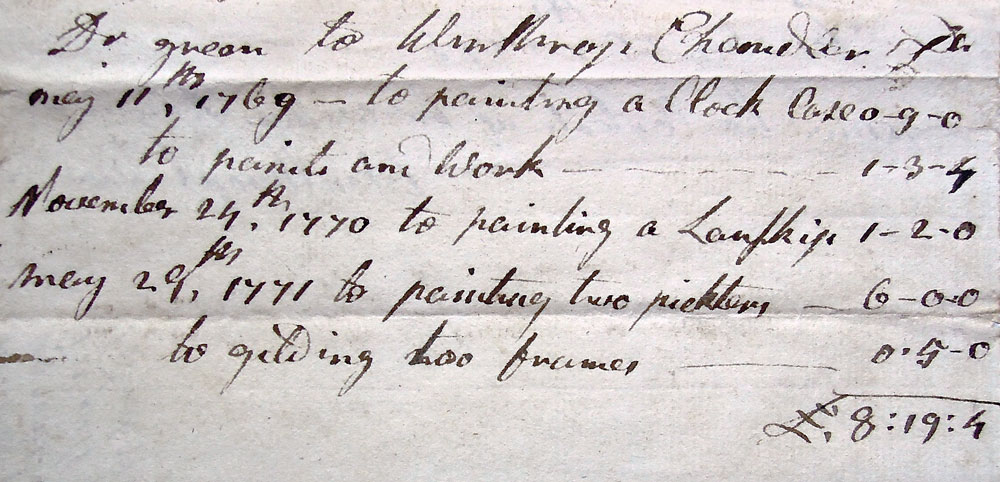

- Fig. 3a: Winthrop Chandler’s receipt for transactions with Dr. John Green. Signed and dated on verso December 25, 1773. Chandler’s first transaction, on May 11, 1769, “to painting of a Clock Case – 9 shillings,” is the only record of Chandler painting furniture. For the same date, Chandler also records “to paints and Work – 1 pound, 3 shillings, 4 pence” for additional unspecified painting. Ink on paper, 5-3/4 x 3-1/2 inches. Private collection.

At the bottom left of the overmantel in figure 1 is the Deacon John Chandler house, the earliest painted image of a multi-gabled seventeenth-century house.5 This landscape was discovered after a painted overmantel depicting a shelf with bound books, now in the Shelburne Museum, Vermont, was removed. Elizabeth and Charles Wood restored the McClellan house from 1968-1976 and discovered a second painting on plaster in an adjoining room, painted by Chandler, of two children playing in front of a house framed by a huge tree. They also discovered a wall painting beneath a chair rail of an almost life-sized fragmentary fox and lions. Both are now covered over with paneled woodwork.6

In around 1767–1769, after his apprenticeship was completed, Chandler painted a landscape overmantel for Elisha Hurlbut, in Scotland, Connecticut (Fig. 2). Nina Fletcher Little believed it to be his first overmantel and maintained it was painted before Hurlbut died in 1769 and not after, because his house was in the estate settlement process until 1775; the heirs, however, gradually sold their separate shares until 1790.7

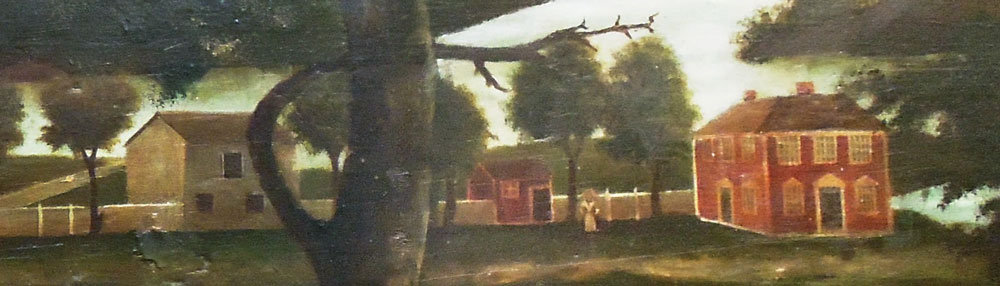

In 1770, Chandler painted a landscape on canvas of the homestead of General Timothy Ruggles of Hardwick, Massachusetts, for Dr. John Green of Worcester (Fig. 3). This is the first American landscape by a known American-born painter with a documented date. A recently discovered receipt written by Chandler on December 25, 1773, summarizes his transactions with Dr. Green over the course of the previous four years (Fig. 3a). The second recorded transaction, on November 24, 1770, is for “painting a Landskip – 1 pound, 2 shillings,” presumably the Ruggles homestead landscape. The third transaction, on May 29, 1771, was for “painting two pickters – 6 pounds” and “gilding too frames – 5 shillings.” These are the portraits of Dr. John Green and his wife, Mary Green. Dr. Green’s wife, Mary Ruggles Green, was the daughter of General Timothy and Bathsheba Ruggles.8 The 1770 landscape depicts her childhood home—the gray house on the left, according to Little. An early drawing of the Ruggles’ house shows that it had five bays, not three as shown in the landscape, an instance where Chandler used artistic license.9

In about 1776–1777, Chandler painted a fireboard showing the “Battle of Bunker Hill” for his cousin Peter Chandler, of Pomfret, Connecticut—the first American landscape of a historical event painted by an American (Fig. 4). The date is based on the Grand Union flags flying over the American forts. Chandler was not present at the battle.10 His brother-in-law, Samuel McClellan, most likely told Chandler about the event. He was made a brigadier general for his service in the Revolution.11 The viewer looks down over Charleston from Breeds Hill, where the battle actually took place.

In circa-1777, Chandler painted a landscape overmantel for Reverend Aaron Putnam’s parsonage, which was built between 1758 and 1762. Putnam was the minister from 1755 to 1813 of the Congregational Church of Pomfret (Fig. 5).12 In 1760 he married Rebekah Hall, who died after being thrown from a carriage in 1773. He married Elizabeth Avery in 1777, and this was the likely reason for commissioning the overmantel.13 In 1871 the parsonage was incorporated into the Ben Grosvenor Inn built by Benjamin Hutchins Grosvenor who lived in the adjacent Esther Grosvenor house.

The McClellan and Putnam overmantels depict a number of houses that still stand today. A comparison between an enlarged view of Chandler’s McClellan house (Fig. 6) and the 1859 photograph already mentioned (Fig. 7), shows that it is an unskilled but faithful representation. The McClellan house, evident by its window configuration, is also shown in the Putnam overmantel in an enlarged view (Fig.8), but here, Chandler removes the porch on the left side of the main house and attaches the small building to it. He also adds another chimney on the right side of the house.

- Fig. 7: Photograph of McClellan Elms, South Woodstock, Conn. This 1859 photograph shows the memorial elms planted by McClellan’s second wife, Rachael Abbe, in commemoration of her husband’s leaving for the Battle of Lexington. The house became known as the McClellan Elms. Between the elms is the public well with its sweep. Courtesy Woodstock Historical Society.

After the 1750s it became fashionable to paint houses inside and out, and in both the McClellan and Putnam overmantels Chandler painted the McClellan house its original ochre yellow color. The color was established by a paint analysis and the discovery of a chip of original paint under a window sill. Chandler was also a house painter and, according to Nina Fletcher Little, Chandler “used his house-painters knowledge” to depict the correct architectural details of his houses.14

Another house in the Putnam overmantel that still stands today is the red hipped-roof house in the center (Fig. 9). This house is likely the Esther Grosvenor house in Pomfret, built in 1725. It is the only hipped-roof house and the oldest house in the town and only 0.3 miles west of the site of Rev. Putnam’s parsonage and is 1.5 miles south of the McClellan house.

A photograph from circa 1890 (Fig.10) shows the Grosvenor house with five bays instead of three as in the overmantel. An architectural survey indicates that it was enlarged in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. Triangular pediments over the windows and doors are missing today and were probably removed during the enlargements. The barns and shed shown in the overmantel are no longer standing. However, the base of a stone wall still remains, indicating a wall once extended to the left of the house as shown in the overmantel. Old photographs confirm the presence of the barn and shed and a written record describes their removal in the 1930s. A paint analysis showed the house was originally red as Chandler depicted in the overmantel.

When the Putnam overmantel was painted, the house was owned by Amos Grosvenor, Esther Grosvenor’s grandson. He owned most of the land in the town center and was one of Rev. Putnam’s most important parishioners. Chandler’s great grandparents, Deacon John and Elizabeth Chandler, and Amos Grosvenor’s grandparents, John and Esther Grosvenor, were all originally from Roxbury, Massachusetts. The Chandlers were among the founders of Woodstock and Pomfret, and the Grosvenors were among the founders of Pomfret. Also, Chandler’s nephew, William Chandler (1754–1844), married Amos Grosvenor’s oldest daughter, Mary, in February 1777, and three months later, Putnam married, which are reasons Chandler included the two houses in the overmantel.

- Fig. 9: Enlarged view of the Esther Grosvenor House from the Putnan overmantel in figure 5. Esther Grosvenor’s husband, John Grosvenor, died in 1691 and she and her six sons moved to Pomfret in 1702. She built three houses, tended the sick of the town, and fought off an Indian attack single handedly. She died in 1738. The house has been owned by the Grosvenor family for nearly three hundred years.

- Fig. 10: Photograph ca. 1890 of Col. Horace Sabin (1810–1894) in front of the Esther Grosvenor house, Pomfret, Connecticut. Col. Horace Sabin was a descendant of William Sabin, a founder of Woodstock and Pomfret. Horace married Emily Grosvenor and stands in front of his father-in-law’s house, the Esther Grosvenor house. Private collection.

The Hurlbut overmantel, the Battle of Bunker Hill fireboard, and the Putnam overmantel show that Chandler employed the traditional compositional approach to landscape painting which had evolved from Claude Lorrain’s (circa 1605–1682) pastoral landscapes, then so admired in America. In these three landscapes, Chandler creates an illusion of space and depth via water (or the land, in the case of the fireboard) weaving into the background and via an aerial perspective.15

Chandler’s training taught him to modify nature to enhance the drama in the landscape. While European painters used Gothic ruins to increase the perception of antiquity, in the Putnam overmantel Chandler showed antiquity and mortality by inserting a large, twisted dead tree (Fig. 11). To increase the sense of tension and ruthlessness in nature, Chandler contrasts a golden eagle at the top of the dead tree, which hunts ducks, one of which is flying away, to the swans preening peacefully. He also contrasts a hound chasing a red fox toward a rabbit frozen in fear, against a peaceful farm scene in the background (Fig. 12).

Chandler knew the people who lived in the houses shown in the Putnam overmantel. He painted a black female servant standing at the doorway of the McClellan house (fig. 8). In the 1790 Federal Census of Woodstock Samuel McClellan had four black slaves. A Caucasian female stands near the Grosvenor house (fig. 9). In the 1790 Federal Census of Pomfret, Amos Grosvenor owned no slaves.

Unfortunately, Chandler’s most active period, 1769–1789, coincided with an economic depression that spanned the American Revolution and its immediate aftermath. His financial difficulties began in 1775, with the start of the war, and continued for the rest of his life. He was not an entrepreneur and relied mainly on a network of family and friends, who commissioned about thirty-five portraits and about a dozen landscapes. He supplemented his meager income by painting houses and furniture, gilding frames and at least one weathervane, and carving a British coat of arms.16

In addition, Chandler had several personal hardships. In 1786 his son Charles died. In 1789, his wife, Mary, went back to live with her parents. Six months later she died of consumption at age thirty-six. Chandler’s remaining five children were sent to live with various relatives. He had been selling his land to relatives for years. In 1790, he left Worcester and moved back to Woodstock, and deeded all of his remaining land to the Township of Thompson in order to pay for his care and funeral expenses. On July 29, 1790, he died of consumption at the age of forty-three, a financial failure, though artistically successful.

-----

Leslie and Peter Warwick are independent researchers and collectors of eighteenth- and nineteenth-century American folk art paintings, furniture, textiles, and stoneware.

This article was originally published in the Summer 2013 issue of Antiques & Fine Art magazine. AFA is affiliated with Incollect.

2. Connecticut Historical Society, Hartford, Connecticut.

3. Nina Fletcher Little, “Winthrop Chandler,” Art in America, 35, no. 2 (April 1947): 78.

4. Ibid, 79.

5. Cheryl R. Wakely, From the Roxbury Fells to the Eastern Vale, A Journey Through Woodstock 1686-2011 (Woodstock Historical Society, Woodstock, CT, 2011), 173, 177.

6. Elizabeth Wood, “A Brief History of the Samuel McClellan House.” Typed notes, undated, in the library of the Woodstock Historical Society, Connecticut.

7. Nina Fletcher Little, “Recently Discovered Paintings by Winthrop Chandler.” Art in America, vol. 36, no. 2, (April 1948): 96–97.

8. Little, “Winthrop Chandler,” 140–142.

9. Ibid., 149.

10. Gerald W. R. Ward, et al, “American Folk” (MFA Publications, 2001), 103.

11. Wakeley, op. cit, 176.

12. “Town of Pomfret…Commemorative Issue” (Pomfret, Conn: Self published, 1963), available at the Pomfret Town Library.

13. A. L. Allen, A Brief History of the Family of Nathan Allen and Mary Putnam…and of the Families of Rev. Aaron Putnam, of Pomfret, Conn… (Poughkeepsie, N.Y. Self published 1895), 41.

14. Little, “Winthrop Chandler,” 153.

15. The water in the Putnam overmantel may be the mile-long Wappaquasset Pond located between the McClellan and Grosvenor houses.

16. Little, “Winthrop Chandler, 84 and 86.