Andrew and Jamie Wyeth: An Artistic Dialogue

Messy Painting and Fleeting Moments

The artistic dialogue between Andrew and Jamie Wyeth was never overt, but exist it did, even if their artistic results diverged (Fig. 1). Andrew said that he wanted to be known as the father of his famous artist son, Jamie; his son remarked that “my father was a great inspiration, and there was a bit of competition between us.” 1

Consider their similarities. Both worked in Pennsylvania and Maine in relative isolation from the mainstream art world. Although both were child prodigies, they spent thousands of hours mastering their craft, seeking and finding the universe they sought to show. Both trained as if they were apprentices, Andrew to his father, N. C. Wyeth, the well-known illustrator, and Jamie to both his father and his aunt Carolyn. They learned the fundamentals through progressive exercises that consisted of mastering chiaroscuro by drawing cubes, spheres, and pyramids; studying the elements of composition; and learning how to work with color. These lessons taught them the rewards of discipline and hard work in their efforts to turn technical proficiency into art. Both would acknowledge that the latter is rarely achieved without mastering the former.

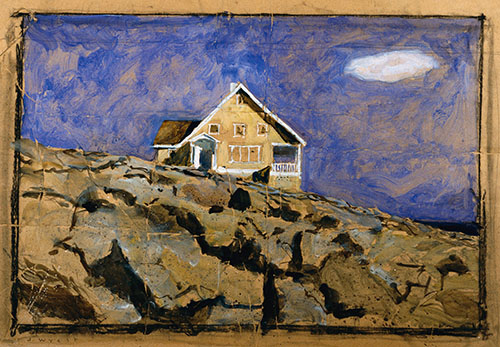

Neither father nor son treated drawings and finished works with any sort of formal hierarchy. Andrew allowed paint to drip on sheets of paper on the floor, and he and his dogs left footprints and paw prints on them (Fig. 2). “These things aren’t intended as paintings,” Andrew pronounced about his drawings or preliminary watercolors. “They were just put down in excitement. I don’t want them to be careful. To me a drawing that’s done to be nice is usually lousy. I only keep them because they’re useful.” 2 Jamie drew and painted on unprimed cardboard and plywood (Figs. 3 and 4 ).

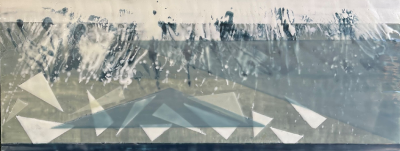

Both used media in a highly unorthodox manner. Even early in his career, Andrew might blot washes to produce inimitable effects for his pen and ink drawings or score through washes of ink with steel-wire brushes, blunt instruments, or his fingernails—all in addition to laying in more washes with brushes and other marks with ink-laden nibs (Fig. 5).3 Being in the moment allowed Andrew to work with media interchangeably and in unorthodox ways. Referring to Spring Beauty (Fig. 6), one of his early drybrush watercolors that incorporated ink, he said: “This is important for the development of my way of seeing reality. Here is a time I used pooled Higgins’ ink, too, to make the silver gray of the bark, for the texture of that bark was fascinating to me.” 4

Similarly, Jamie often paints in mixed media, sometimes, for example, with watercolors worked and applied almost like oil but without the greasiness of oil. “With mixed mediums I’m able to—with watercolor and wash—have it completely flat and then varnish one section with oils, which thrilled the hell out of me. I thought I had made a great discovery.” 5 Like his father, he doesn’t want to paint under any fixed method or system, and instead treats each work individually as its images demand, which helps explain his obsessive search for new and interesting materials to experiment with.

By allowing himself full rein with a multitude of media applied any which way, Jamie ultimately began to distinguish himself from Andrew, and thereby repeated his father’s success in finding his way independent of N. C. And yet, as Andrew and Jamie emerged as their own artistic personalities, they nonetheless were deeply entrenched in the lessons of N. C.’s studio exercises. Andrew used his formal means for introspection, while Jamie defaulted to extroversion, finding great satisfaction in lush chromatics, enigmatic subjects, and intentionally stilted compositions. He learned to trust in his own peculiarity.

In interviews, Andrew seemed to want people to know that he improvised his techniques instead of thinking that he was a “tight” painter (Fig. 7). “My father was a messy painter,” Jamie claims, “and that’s what the world doesn’t necessarily know about him.”

“I honestly consider myself an abstractionist,” Andrew said. “There’s another core—an excitement that’s definitely abstract.” He made other statements along these lines: “You know, sometimes I kind of exalt in the fact that a page will be partly dirty before I start. I like that because it keeps me somehow flexible. If you have too beautiful a sheet of paper and you preserve that with great care, you dare not paint it that way. You get very picky and finicky and particular.” In the same lengthy exchange with Metropolitan Museum director Thomas Hoving, he revealed, “I do not like to be held in by a line when I am working in watercolor or putting down a color note because that freezes me.” 6

Jamie describes pigments as “edible,” and he prefers to keep them in a gel-like state for as long as he can, sometimes adding in clove oil to retard their dehydration. He uses a range of manufacturers’ oil paints—from Golden to Rembrandt to Gamblin—and even seeks out fluorescent paints used by lobstermen for their buoys, as he did for Inferno, Monhegan (Fig. 8) He came to this way of working, he says, through Andy Warhol. “The guy who did his paint still helps me with paint, and he found a paint that has honey in it. The problem with watercolor is that if you build up impasto, it has no elasticity. It will just crack and break. Oil you can just bend and it won’t crack. So this stuff seems to have worked pretty well. The honey is clear and honey, of course, lasts forever. The honey is in the pigment itself.” 7

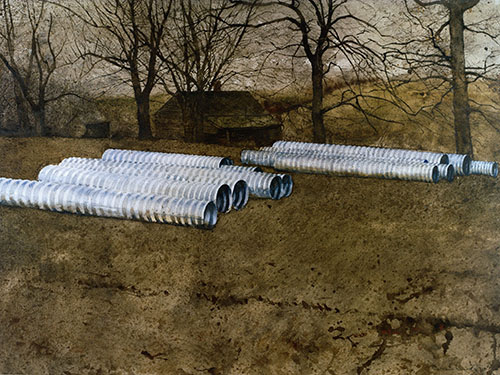

Similar to his father’s knack for capturing a fleeting moment, Jamie’s ideas come from a personal wellspring and response to his experiences as a member of a dynasty of artists, which informs how he sees the world. Jamie has observed that when viewers see the name “Wyeth” on a label next to a work by his father or him, they stop looking. Although Jamie’s settings may look like the Brandywine Valley or Midcoast Maine of his father’s works, they are more a scenic backdrop for his quirky sensibility, which seeks out overlooked or peculiar objects such as docking posts, plow blades, buzz saws, storage tanks, or sewer pipes. One analogy—imperfect but perhaps helpful—is to look at his compositions as if they were repurposed accidental photographs; unintended compositions fraught with meaning. We are sometimes blind to this effect, because Jamie also imbues these mundane objects with scintillating surfaces through dazzlingly unorthodox approaches to painting.

Had he taken his cue from his father, say, in subject matter? “No, not really. In fact it was just the opposite.” Jamie told a story about Tom Clark’s house, seen in the distance of the broad landscape in his painting The Big Inch (Fig. 9). Jamie knew that Andrew was inside—“I saw his Jeep Wagoneer parked there”—working on any number of works, such as Garret Room (Fig. 10), which shows Tom reclining on a patchwork bedcover. “I wanted to paint a composition with subject matter such as the massive sewer pipes that countered the exquisite and precise finish of my father’s paintings,” Jamie said about that time. But Jamie also remarked that there were coincidences, such as in 1997, when unbeknownst to each other, both worked on paintings that included the Hale-Bopp comet that passed over Earth that year.

And, like his father, Jamie developed his own way of talking about his art early in his career, perhaps as further testimony to his own push toward independence. He frequently substitutes anecdotes for explanation when he talks about his working methods and where his images and narratives may have come from. He enjoys telling stories about his paintings because the works are so intensely personal, as with the story behind Winter Pig (Fig. 11). Jamie took an interest in painting a pig that hated snow. He brought a heater into the beast’s sty and, crouching down inside, began painting its portrait. Jamie was called away by the farmer who owned the pig (named Den-Den, the 600-pounder later became Jamie’s pet), and upon returning, discovered that the pig had scarfed down all of his pigments—some of them quite toxic. For the rest of the week, the pig produced rainbow-colored droppings, amazing both the farmer and the artist. Another is his background story for Pigeons (Fig. 12): he would wind up a mechanical toy pigeon on wheels, let it loose, and scare the living hell out of real pigeons.

This article is adapted from Wyeth: Andrew and Jamie in the Studio, published in October 2015, by the Denver Art Museum in association with Yale University Press, and accompanying an exhibition of the same name at the Denver Art Museum, November 8, 2015–February 7, 2016, and Museo Thyssen-Bornemisza, Madrid, March 1–June 19, 2016. Used by permission. For further information, visit www.denverartmuseum.org or call 720.865.5000.

Timothy J. Standring is Gates Foundation Curator of Painting & Sculpture at the Denver Art Museum and curator ofWyeth: Andrew and Jamie in the Studio.

This article was originally published in the Winter 2015 issue of Antiques & Fine Art magazine, a digitized version of which is available on afamag.com. Antiques & Fine Art and AFAmag are affiliated with InCollect.com.

2. Quoted in Richard Meryman, Andrew Wyeth: A Secret Life (New York: HarperCollins, 1996), 245.

3. Andrew Wyeth and Thomas Hoving, Andrew Wyeth: Autobiography (Boston: Little, Brown and Company, 1995), 11.

4. Ibid., 23.

5. Jamie Wyeth, Farm Work (Chadds Ford, Pa.: Brandywine River Museum, 2011), 86.

6. Thomas Hoving, Two Worlds of Andrew Wyeth: A Conversation with Andrew Wyeth (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1976), 110.

7. Wyeth, Farm Work, 88.

-copy1.jpg)