The Instruction of Young Ladies: Arts from Private Girls’ Schools and Academies in Early America

This archive article was originally published in the Winter 2016 issue of Antiques & Fine Art magazine

From colonial days into the nineteenth century, most girls were taught the essential practical skills needed to manage and maintain a household from their mothers and other older female relatives. While girls from well-to-do families had access to more sophisticated schooling and could develop refined tastes and accomplishments, their expected roles differed little from those of the less fortunate.

The curriculum for young ladies of means who attended private boarding schools and female academies in early America included a wide range of artistic endeavors in addition to the reading, writing, and arithmetic emphasized in public schools of the time. Students were taught pictorial needlework, weaving, rug hooking, drawing, and painting in multiple media. This decorative “fancy” work tested young women’s skill and also offered a socially acceptable artistic outlet.

While some of these efforts were inevitably pedestrian or rote, a surprising number form a body of work that is significant in the history of American art. Equally important are the key roles that women educators played in the development of America’s education system and in the opening of higher learning to women in the decades before and after the Civil War. Art was a distinguishing element of young women’s education in America from the late seventeenth century on, and both the artwork produced in private schools and the teaching later carried on by women who attended them had major and lasting impacts on American society and culture.

This is one of the few extant seventeenth-century American needlework pictures. Sarah Phillips (1656–1707) was the daughter of an English-born, Harvard-educated minister, the Reverend Samuel Phillips, whose parents brought him to Massachusetts in 1630, when he was five. Sarah is believed to have studied at a private school in Boston, where she probably acquired her skills in fancy needlework and stitched her picture around 1670.

While Philips’ picture is made up of elements commonly found in seventeenth-century English pattern books and needlework—elegantly dressed upright figures, a central tree of life, a depiction of the prodigal son, and an array of animals, birds, insects, and flowers—it is worked in wool on a wool ground rather than the silk on satin typical of English embroideries. In addition, the colorful, imaginative, and playful freedom of Phillips’ well-balanced composition sets it apart from comparatively stiff English work.

This sampler, which is signed by Lydia Hart and dated 1744, belongs to the earliest known group of related American samplers. Like the other very similar pieces in the group, which were made in Boston between 1724 and 1754, Lydia’s sampler depicts Adam and Eve in the Garden of Eden, surrounded by “every beast of the field, and every fowl of the air” while standing on either side of the tree of knowledge of good and evil, whose fruit God had admonished them not to eat lest they “surely die.” Each of them holds an apple, but the snake that is wrapped around the central tree faces Adam rather than Eve, whom both Adam and God later blamed for the Fall. Hart’s sampler is also unusual because she framed the central image with a subtle floral border, an innovation that would become standard in later needle works.

Ann Grant was a daughter of a prominent East Windsor, Connecticut, family. In the summer of 1767, when she was nearly twenty years old, she traveled to Boston to study embroidery with Jannette Day, a Scottish woman who had emigrated to the city and opened a school

there in 1756. Mrs. Day, who went by both Jannette and Jane, advertised her business in a number of regional newspapers, which is likely how Ann Grant and her parents learned of it.

After three months of study, Day presented Grant with a bill for forty-one pounds, more than thirty-one of which were for embroidery supplies, including 100 skeins of silk, sixty-one yards of “silver gold,” and nineteen yards of “Gold Flatt.” Day returned to the British Isles in 1768, but the following year, Grant continued her study with the Misses Ann and Elizabeth Cummings, who had taken over Day’s school. She spent seventeen weeks at the Cummings’ school with the Cummings sisters, during which time she completed this family coat of arms worked in silk with gold and silver threads and metallic raised work.

Pictures that combined needlework and watercolor became increasingly popular in the early decades of the nineteenth century as skills in painting gained social ascendency over handwork. Among the influences on this transition were increased literacy and the wider availability of prints in books. This silk embroidery and watercolor on satin of the lovers Palemon and Lavinia created by Sophia Burpee (1788–1814) in about 1806 demonstrates all these influences. Sophia Burpee’s source was a print illustrating the Scottish poet James Thomson’s poem Autumn, from The Seasons, a long, descriptive poem first published between 1726 and 1730 that remained immensely popular well into the nineteenth century. Thompson’s tale of Palemon and Lavinia, which he freely adapted from the Biblical story of Ruth and Boaz, was printed separately in the late 1700s and became the subject of numerous paintings, prints, and needlework.

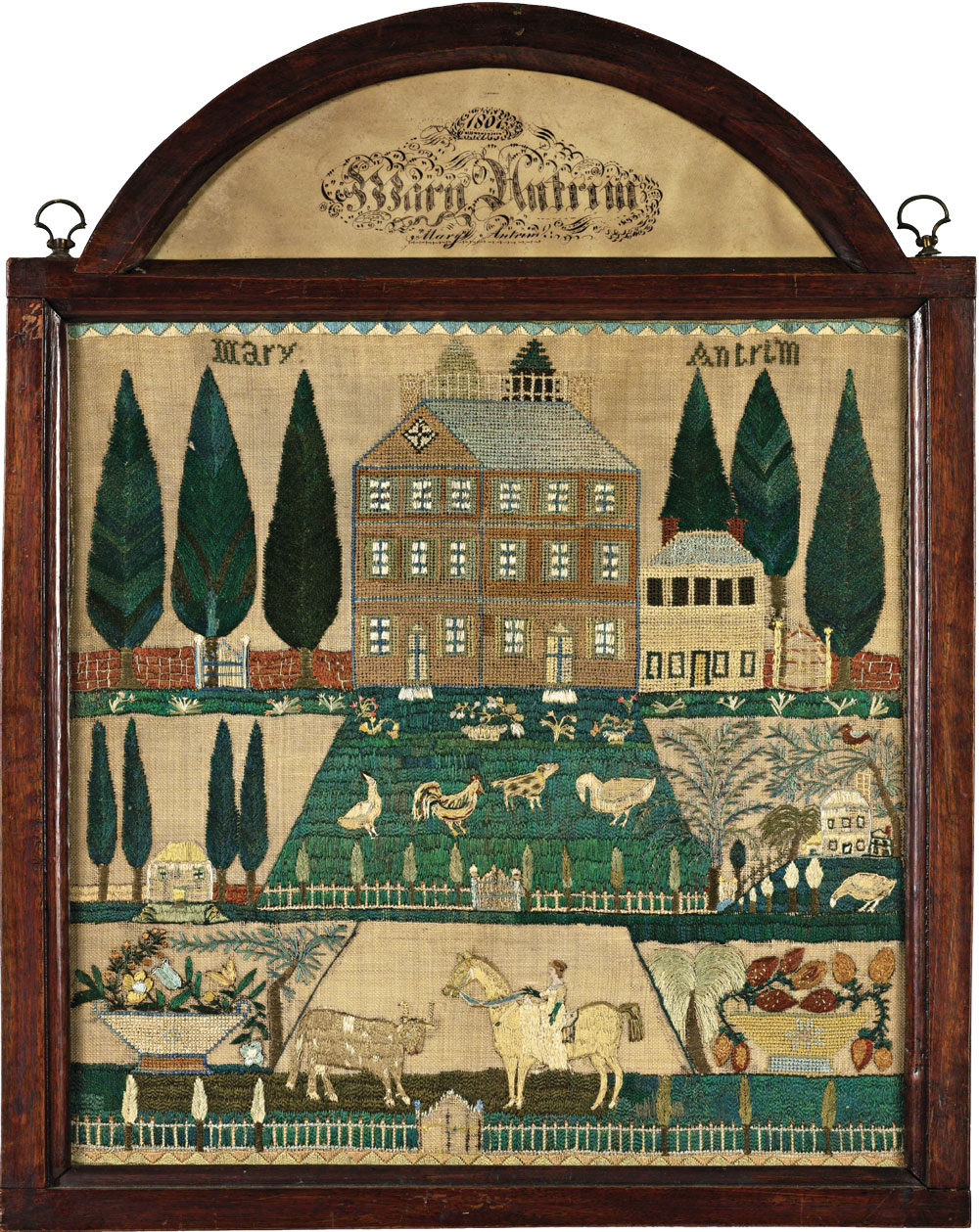

Mary Antrim was one of eight children born to John Antrim (1766–1849), who was a weaver, and his wife Sarah Rogers (1772–1815). Her sampler belongs to a recently recognized group of six closely related pieces worked by girls in Burlington County, New Jersey. Mary’s is dated 1807, while all the others are dated 1804. However, Mary’s date appears only in calligraphy on paper at the top of her fancy frame, so it is likely that she too stitched her piece in 1804 and framed it later. All the samplers are organized in three bands of pictorial work and share a central figure of a young woman with a paper face and bonnet who is sitting sidesaddle on a horse in the bottom band. All six are believed to have been made under the instruction of a single teacher, most likely at the Society of Friends’ School in Upper Springfield, New Jersey.

Hannah Pearson Cogswell, who was twenty when she painted this watercolor of herself and her older sister Julia teaching a class of girls at Atkinson Academy, offers a rare contemporary look inside an active classroom.

The Academy, which was founded in 1787 as an all-boys school and began its first term in 1789, started admitting girls after it was incorporated in 1791, the year of Hannah’s birth. The sisters’ father, Dr. William Cogswell, was one of three founders of the school and president of its board, and their older brother, also named William (1788–1850), attended the Academy along with his sisters and other siblings before graduating from Dartmouth College in 1811. Like his sisters, William also taught at the Academy when he was young, and served briefly as its principal.

This unusual table is a late example of a memorial to George Washington. The octagonal top of the table carries a detailed view of Mount Vernon. Like other images of America mourning Washington, the source of this image can be traced to England, in this case to an aquatint published by Francis Jukes in 1800. As is the case with examples from other New England schools, this table’s decorations extend to its legs, which are entwined with vines. It differs from other known schoolgirl tables, however, in that it is made entirely of white pine rather than more typical birch or maple and was painted white before being decorated.

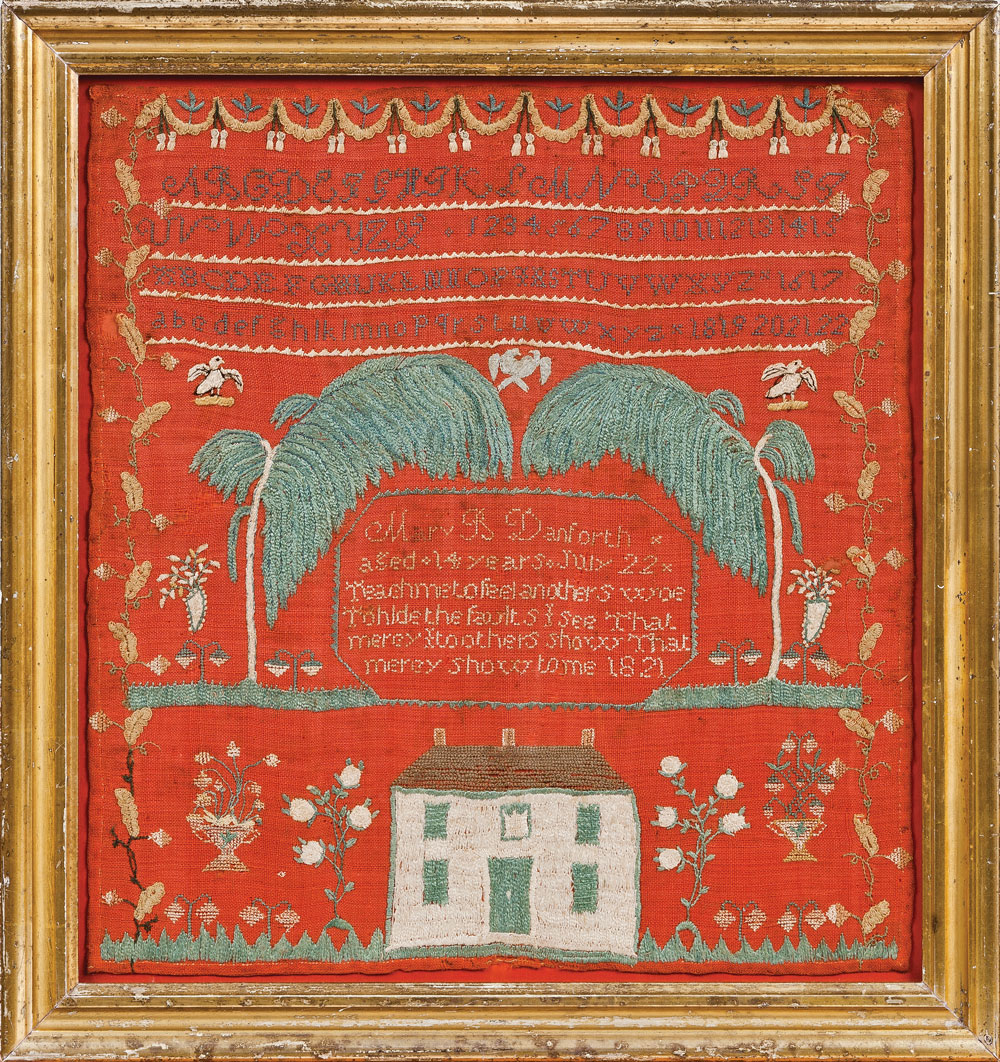

Two years before she made the mourning picture that is also included in this exhibition, Mary Danforth created this equally distinctive and imaginative sampler worked in silk on linen that had been dyed a deep rich red.

Samplers like Danforth’s that were produced in the female academies founded after the Revolutionary War turned from religious to domestic themes, and many depicted the school buildings in which they were made.

Scenes like this were often painted as aides to the study of American history. The central image was probably taken from a print source, which the student surmounted with a pair of American flags and the Great Seal of the United States. The front of the seal, which was adopted in 1782, features a spread-winged bald eagle holding an olive branch in its proper right or dexter talon, thirteen arrows in its sinister (proper left) talon, and a scroll bearing the motto E pluribus unum in its beak.

- Dome-Top Box with inset watercolor panels, ca. 1823–1824 (on cube), attributed to Emeline M. Robinson Kelley School, Portsmouth, New Hampshire. White pine, leather borders, brass-headed upholstery tacks, watercolor and ink on paper under original glass panels, 3-7/8 x 7-7/8 x 4-1/8 in. Collection of Jane and Gerald Katcher.

This is one of five distinctive wooden boxes with inset watercolor panels that are attributed to a Portsmouth, New Hampshire, school operated by Emeline M. Robinson Kelley between about 1824 and 1833. Although two of the boxes have dome-shaped lids and the three others are flat-topped, their similar construction details suggest that all were made by the same craftsman. The watercolors portray well-dressed young men and women and naval officers in a variety of combinations with decorative floral frames and borders. This example and one of the flat-topped boxes carry the highest quality watercolor inserts and are believed to have been painted by Emeline M. Robinson Kelley herself, while the similar but less detailed watercolors on the other three were likely executed by her students.

This octagonal trinket box was made of pasteboard rather than wood. As the name suggests, pasteboard was made by pasting layers of paper together to form more substantial “boards” that could be cut and assembled into boxes. While not nearly as sturdy as wood, pasteboard boxes were inexpensive and easily made and were widely used for storage of small items in early nineteenth-century homes. The top of this box carries a watercolor painting of a classic New England church, while the other seven sides are decorated with a variety of fruit and floral motifs.

This unusual and evocative mourning picture was executed by Mary B. Danforth of Manchester, Massachusetts. Her Memorial to Enoch H. Long, which is dated 1823, depicts a line of twelve children and adults in formal mourning attire beneath a pair of bending weeping willow trees. The mourners ascend in height, from youngest to oldest, as they approach the urn-shaped memorial, which reads: “Sacred to the memory of Enoch H. Long/who departed/this life June 28, 1823/Aged 6 years, 6 m.”

The composition is further enriched by its combination of silk embroidery and watercolor, floral borders that include a row of miniature willows beneath the main scene, and inked paper inserts on the monument and in the bottom border. Enoch was the brother of Mary Danforth’s future husband, Rufus Long, whom she married in 1826.

Mary Hollister, who was just eleven years old when she painted her masterpiece, drew the hemispheres of the world on two large sheets of paper. Her work includes fanciful outlines of various countries filled in with vibrant strokes of watercolor and embellished with calligraphic inscriptions. She topped the Western Hemisphere with a patriotic American eagle and shield and put a hot air balloon above the Eastern Hemisphere, perhaps as a symbol of adventure in far-off lands. The entire work is covered with minute penwork marking everything from the waves in the oceans to well-executed mariner’s compass motifs. She also included her instructor’s name, S. Cole, although we do not know who she or he was.

Mary Hollister was born in Burnt Hills, New York, a hamlet within the town of Ballston, on May 8, 1820, and her inscription indicates that she completed this work on March 24, 1832.

A theorem-painted face screen, which women used to shield their faces from the heat of a fireplace fire, is seen in this portrait of Helen Vreeland painted by an unknown New Jersey artist in 1841. On the reverse of the painting, a family member wrote, “She is painted in a bridesmaid’s dress at the age of eighteen. She made the fan.”

An exhibit at the Fenimore Art Museum, Cooperstown, New York, The Instruction of Young Ladies: Arts from Private Girls’ Schools and Academies in Early America, curated by Robert Shaw, focused on such works created during this time, while exploring the history of private female education in the United States and the key role of women educators in the growth of this country’s educational system. The exhibition was on view from September 24 through December 31, 2016. For information call 888.547.1450 or visit www.fenimoreartmuseum.org.

-----

Robert Shaw is an independent scholar and curator specializing in folk art and studio crafts.

This article was originally published in the Winter 2016 issue of Antiques & Fine Art magazine, a digitized version of which is available at afamag.com. AFA is affiliated with Incollect.

_.jpg)