Classical Elegance for Lafayette’s Visit to Boston, 1824

|

| Fig. 1: Grecian couch made by Isaac Vose & Son and carved by Thomas Wightman for Lafayette’s visit to Boston in August 1824, and sold at auction a week after his departure. H. 35¼, W. 85, D. 24⅜ in. Birch, mahogany, rosewood graining, oil gilding, brass, original underupholstery, modern stamped wool plush fabric and trims. The purchaser was hardware merchant John Odin, whose 1854 probate inventory listed a “couch from Lafayette’s visit,” and whose step-grandson, Day Otis Kellogg, donated it to the Massachusetts Historical Society in 1859. The couch has been reupholstered based on a large remaining fragment of original stamped red plush. Historic New England; Gift of the Massachusetts Historical Society (1923.507). Photo by David Bohl. |

| |

| Fig. 2: Jean Marie Leroux after Ary Scheffer, Lafayette, Paris, 1824. Engraving, H. 32, W. 25 inches. Lafayette considered this the best image of him and brought several copies with him to give to friends during his grand tour of the United States. Copies were also sold in Boston and other cities the French hero visited. This print, in its original frame, bears the label of Xenophon H. Shaw, “Looking Glass & Picture Frame Manufacturer” of Salem, Mass. The Colonial Society of Massachusetts (3.30). Photo by David Bohl. |

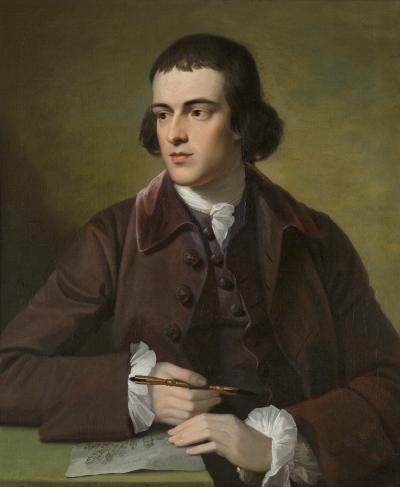

Research into the history of a stylish rosewood-grained couch attributed to Isaac Vose & Son (1819–1825), a centerpiece of a new exhibit at the Massachusetts Historical Society (Fig. 1), revealed hitherto unknown details of General Lafayette’s visit to Boston in 1824 (Fig. 2) and led to the discovery of a cache of documents related to some of Boston’s best craftsmen at the time.

At the outset, it was unclear if the couch in question could be the “couch, made for General Lafayette when he visited Boston,” which was donated in 1859 to the Massachusetts Historical Society and recorded that year in their Proceedings.1 The couch had subsequently been given by the MHS to Historic New England (then Society for the Preservation of New England Antiquities) in 1923 with no provenance. Historic New England’s accession file contains only correspondence about its transfer, some later letters, and fragments of its original red plush upholstery fabric and trim tape. Its association with Lafayette had been forgotten by that time.

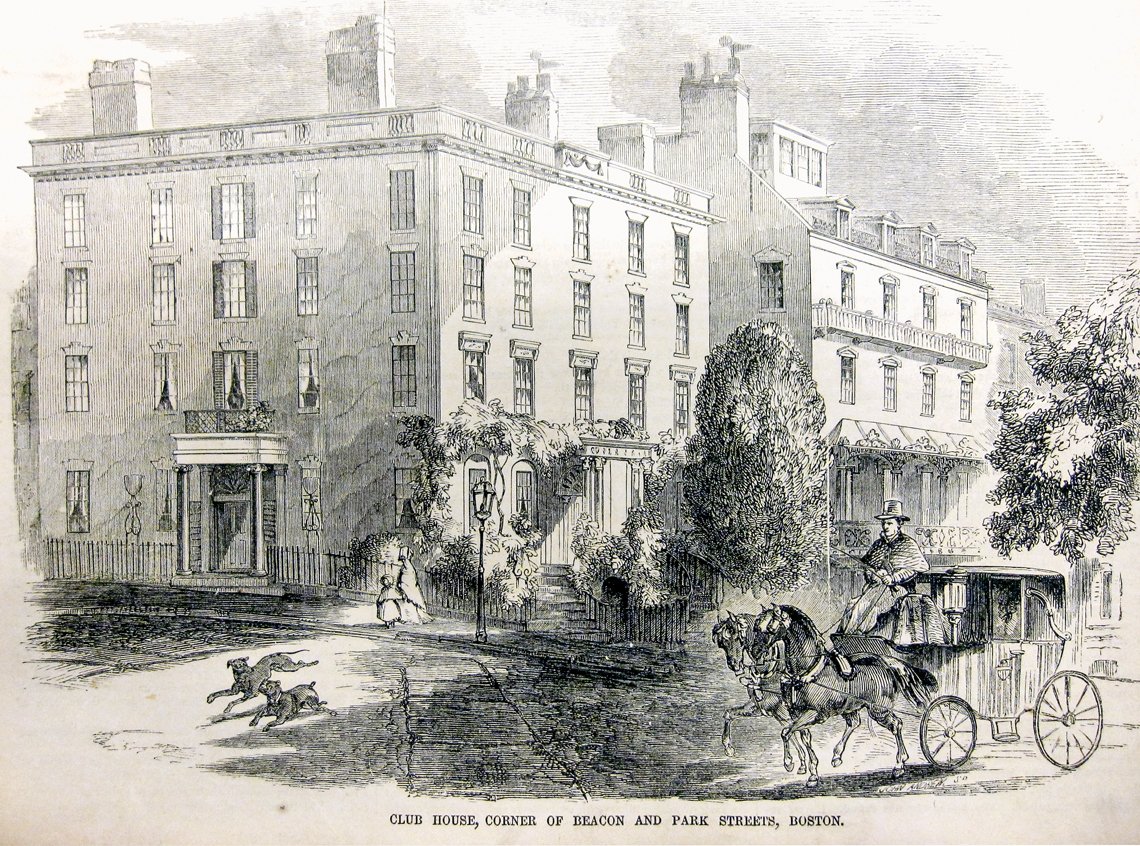

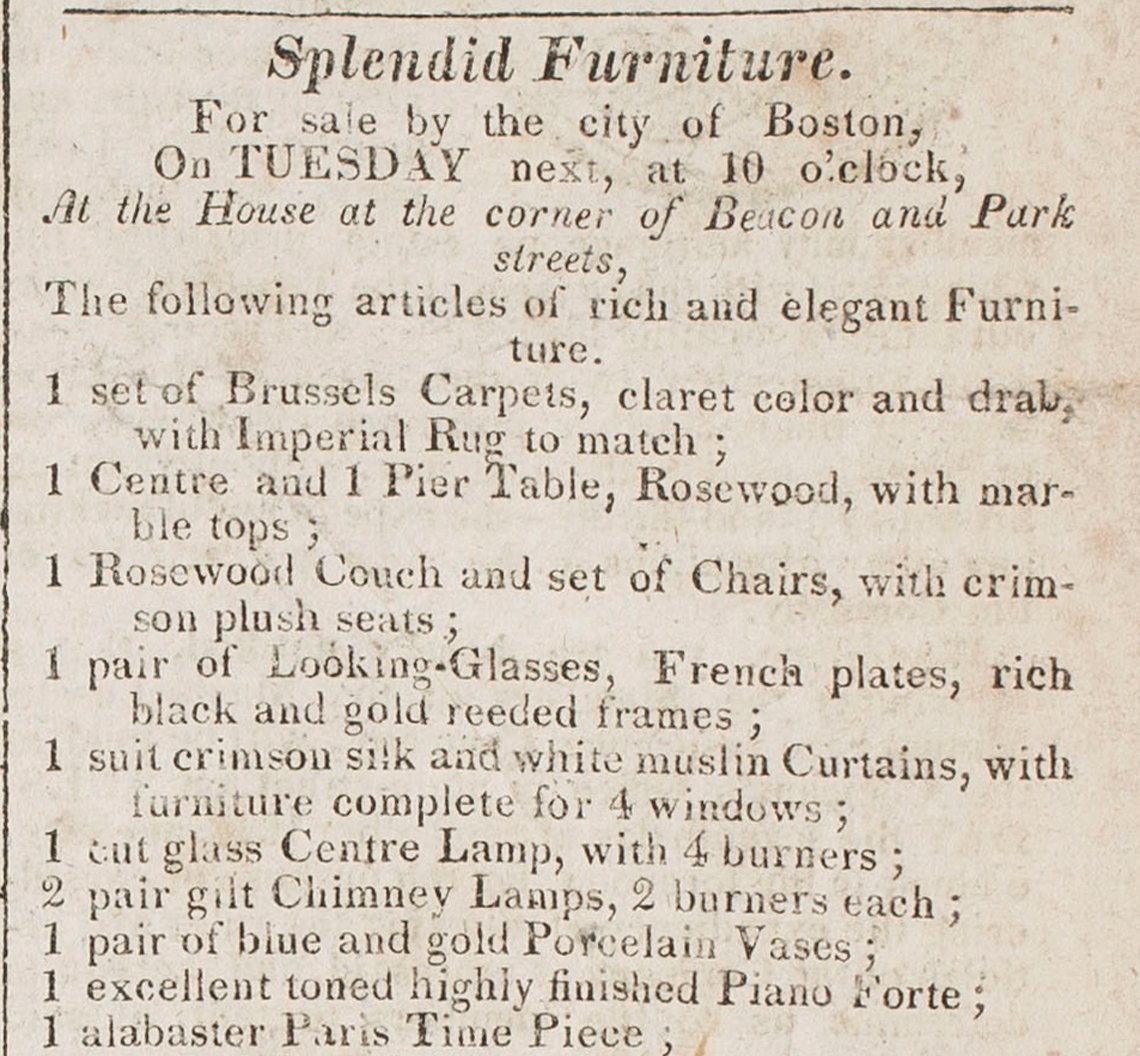

Lafayette stayed at what is now known as the Amory-Ticknor House directly opposite the Massachusetts State House (Fig. 3). A subsequent auction of “SPLENDID FURNITURE” held on behalf of the city of Boston “At the house at the corner of Beacon and Park streets,” the exact location of the Amory-Ticknor House, occurred only a week after General Lafayette left Boston to continue his grand tour of the United States to commemorate the start of the American Revolution (Fig. 4). Although the auction notice did not explicitly state a Lafayette association, the listings match detailed descriptions in several craftsmen’s invoices to the city, including two from Isaac Vose & Son.

Boston’s Board of Aldermen’s Papers for 1824 include extensive records of the city’s preparations for the visit.2 Boston had just incorporated as a city in 1822, with aldermen now serving as the top ranking administrative body. Two thick folders of documents include copies of the formal invitation of Mayor Josiah Quincy to Lafayette and the general’s florid acceptance; correspondence of the aldermen with a “club” of Boston gentlemen offering their so-called “Subscription House” to the city for Lafayette’s lodgings, and the city’s acceptance;3 complaints from citizens that the city’s offer to host Lafayette should be paid for by the entire citizenry, not just by an elite group of leading men; and dozens of receipts from local vendors supplying tents, food and drink, the tolling of bells, the firing of canon, and the furnishings for the accommodations of the general and his entourage.

| |

| Fig. 3: Club House, woodcut, in Ballou’s Pictorial, May 26, 1855 (Vol. VIII, no. 21). The house built by Thomas Amory in 1804 and rented by the city of Boston for use as Lafayette’s lodgings was noted in one newspaper as the “most suitable abode which could be selected for the Guest of the nation.” It was strategically chosen for its location opposite the State House and Boston Common, which could accommodate the throngs of people who attended the numerous public events, parades, and addresses. http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ |

The more than 100,000 visitors who attended the week’s festivities and events held between August 24 and 30, 1824, far exceeded Boston’s entire population of 55,000. For the grand entrance procession, Lafayette was seated in an open barouche drawn by four white horses and accompanied by Governor William Eustis and Mayor Josiah Quincy. When they reached Boston Common, twenty-five hundred schoolchildren stood in well-ordered ranks, each with a white sash imprinted with a miniature portrait of the hero (Fig. 5). Local merchants rushed to cash in on the fervor by producing souvenirs, including ribbons and women’s gloves printed with the general’s portrait (Fig. 6). Formal speeches at the State House lasted until late in the day when Lafayette finally retired to his appointed lodgings across the street.

The furnishings supplied for seven rooms in the four-story brick house must have been among the finest ever assembled in Boston. Among the receipts for purchases by the city are two signed and receipted invoices from Isaac Vose & Son, both dated just days before Lafayette’s arrival, and only six weeks after the date of the visit was finalized. One two-page bill lists seventy-eight pieces of furniture and indicates the rooms they were to furnish. Also listed by room are other items Vose supplied: two large mirrors, candle branches and eighteen fancy lamps, most with “ground moon shades” (Fig. 7).4 A second receipt to the city from the firm details three “French Bedsteads” and four wall brackets to support some of the lamps (Fig. 8). No other receipts for furniture are included in the folders, so Vose apparently had the exclusive contract. All would have been made in the Vose shop while the leading Boston cabinetmaker Thomas Seymour was foreman of the workshop. The short six-week period the workmen had to make these suites of furniture suggests much of it was probably supplied from the firm’s existing inventory but with the upholstery and gilding added to enhance the treatment of each room.

|  | |

| Fig. 4: Detail of the auction notice for “SPLENDID FURNITURE,” in The Evening Gazette (Boston, Mass.), Sept. 4, 1824. The week after Lafayette’s visit, the city sold the curtains, carpets, lighting devices, linen, silver and furniture at public auction on September 7, 1824. The advertisement does not include Vose & Son’s name. It concludes: “The above Furniture is all of the most superior workmanship and materials, and presents the richest assortment that has ever been offered at public Sale in this city.” American Antiquarian Society (catalog # 2399). | Fig. 5: Silk sash with engraving. The tens of thousands of people who swarmed Boston to get a glimpse of the Revolutionary War hero all wanted souvenirs. Local merchants produced these in huge quantities, including sashes imprinted with portraits of Lafayette. This sash was worn by Lucy Lincoln, a teacher of some of the twenty-five hundred schoolchildren who assembled in Boston Common to greet the General. Alan R. Hoffman collection; photo courtesy of the Massachusetts Historical Society. |

|  | |

| Fig. 6: Leather glove with engraving. Women’s gloves imprinted with Lafayette’s portrait were also popular souvenirs. Lafayette reportedly politely declined the honor of kissing the hands of women wearing such gloves, not wanting to salute an image of himself and appear vain. Collection of the Massachusetts Historical Society, removed from Anna Cabot Lodge Scrapbook, vol. 22, Henry Cabot Lodge Papers (Ms. N-1592). | Fig. 8: Wall bracket (one of a pair), attributed to Thomas Seymour, carving attributed to Thomas Wightman, possibly for Isaac Vose & Son. Boston, 1815-1824. This lighting bracket in the English Regency style may be similar to the four listed on the receipt to the city of Boston from Vose & Son. Wall brackets like these are depicted holding lighting devices in Henry Sargent’s well-known painting The Tea Party (Museum of Fine Arts, Boston). Isaac Vose & Son also supplied lamps and candle branches to the city for the occasion. The Winterthur Museum; Bequest of Henry Francis du Pont (1957.0701.001). |

| |

| Fig. 7: Detail of page 1 of Vose & Son’s invoice to the city of Boston for “use of Furniture & Lamps for Rooms furnished for Genl La Fayette & Family,” 1824. Vose’s invoice lists the seventy-eight pieces of furniture he supplied for Lafayette’s lodgings and includes in the “Lower Drawing Room . . . 1 [Rose Wood] Couch coverd [sic] with Crimson plush” (illustrated in figure 1). Sixteen chairs of similar rosewood grained finish and upholstery were supplied en suite. Board of Aldermen’s Papers, 1824, City of Boston Archives. |

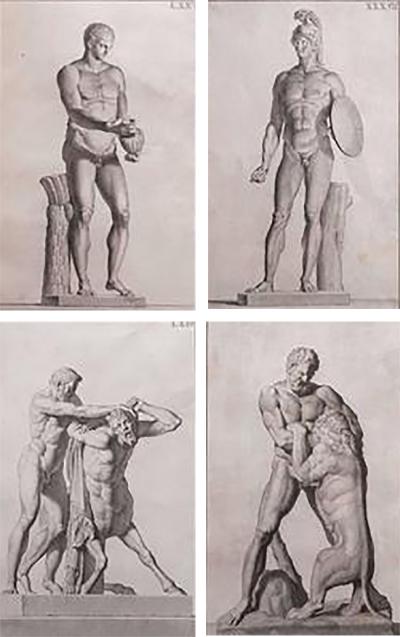

Vose’s superb “Rose Wood Couch coverd [sic] with Crimson plush,” “14 Rose Wood Chairs,” and two armchairs “covered with do [ditto]” were in the French style. Among all known Vose-made furniture, the couch is one of only three pieces with gilt carvings. This was clearly designed to appeal to the perceived taste of the Frenchman, as were the “French beds,” “French Secretary Glass Doors,” and probably the pairs of rosewood and mahogany pier and center tables in the lower and upper drawing rooms. The superb carvings with immaculately carved scrolling details on the couch are firmly attributable to Thomas Wightman, Vose’s London-trained contract woodcarver, whose name is inscribed in ink on the underside of the front rail. The perfection of the long, scrolling curves and classical leafage is typical of the work of Boston’s finest carver.

Vose’s charge for the luxury furnishings on the principal receipt was $3554.50 and $110 for the beds. Surprisingly, his actual bill to the city was for $355.45, only 10 percent of the actual value, with the 90 percent balance to be paid later. This probably allowed the aldermen to avoid accusations by the citizenry of wasting taxpayers’ money on what were obviously luxury furnishings for short-term use. The city’s sale at auction of the entire group just after Lafayette’s departure presumably would have covered Vose’s remaining balance and earned a substantial additional premium for the association with the famous Revolutionary War hero.5

No detailed descriptions of the rooms furnished for the occasion survive, but the invoices, combined with the auction notice, help paint a picture of how elegant and colorful they must have been. Accompanying Vose’s bills were equally detailed bills from leading Boston upholsterer Thomas Hedges, prominent gilder and looking glass maker John Doggett, carpet vendors Ballard & Prince and Joseph Bacon, and an offer by John Mackay of the loan of “a Piano Forte, of American manufacture made in Boston, that will do credit to the manufacturers of our Country” (Fig. 9). The instrument was actually made by his financial partner Alpheus Babcock.

|

| Fig. 9: Pianoforte, marked “Made by A. [Alpheus] Babcock for G. D. Mackay” on the nameboard, ca. 1823; piano stool by unknown maker. Dr. Benjamin Shurtleff purchased this pianoforte and the stool, which retains its original upholstery, for his daughter, Sally Shurtleff Freeman, at the 1824 auction. She took it to Hillsboro, Illinois, when she moved there with her husband in 1841. The piano never lost its association with Lafayette and remained in the same house until it was donated to Historic New England in 2005. Courtesy of Historic New England; Gift of Evelyn Sawyer Tobias (2005.23.1A, B). |

|

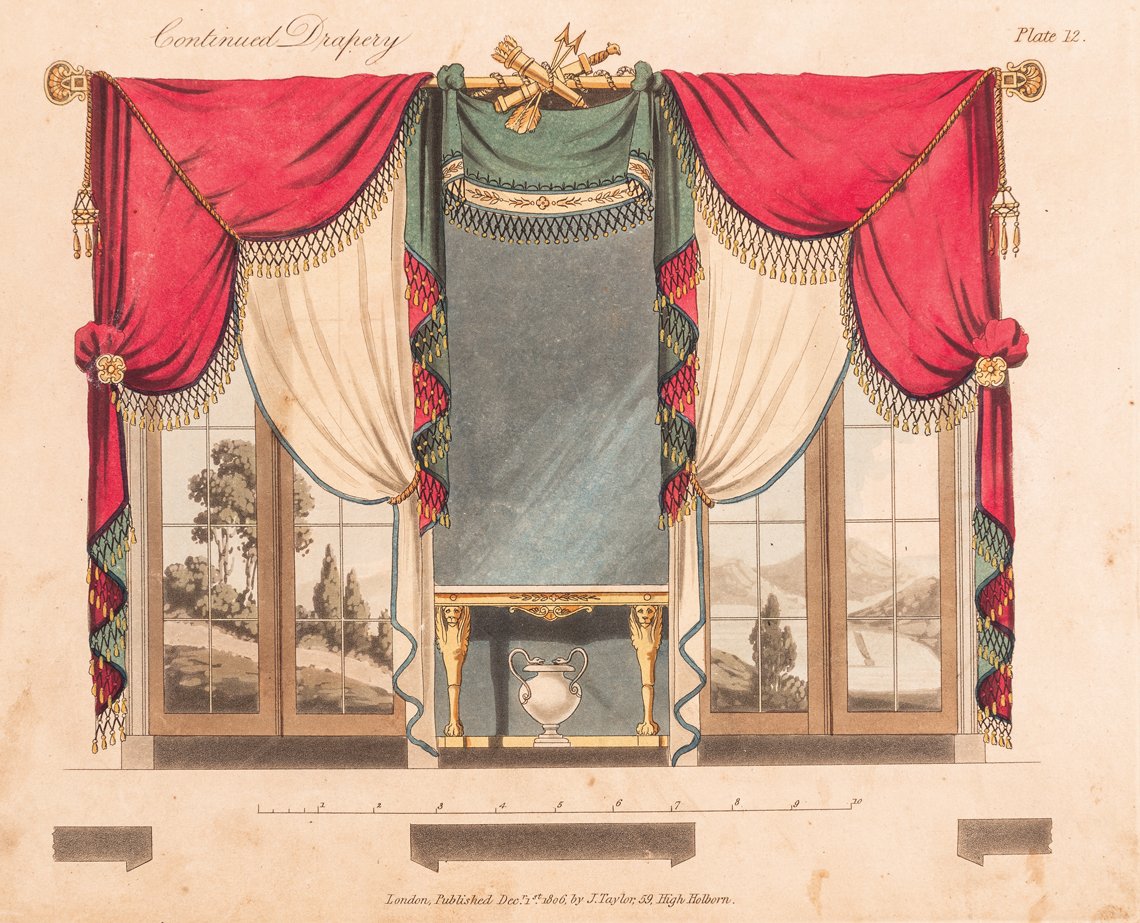

| Fig. 10: Continued Drapery, plate 12, in George Smith’s A Collection of Designs for Household Furniture and Interior Decoration (London, 1808). The wording in Thomas Hedges’ bill suggests that he created a treatment in this style for two of the windows in the main reception room of Lafayette’s lodgings. Hedges substituted a carved and gilded wreath for the center trophy seen here. Courtesy of the Winterthur Library, Printed Books and Manuscripts Collection (NK2542 S64c). |

Thomas Hedges, another English emigré, worked with Vose as a limited partner until mid-1823; beginning in 1824, he advertised himself as an “Interior Decorator of Fashionable Apartments and General Upholsterer.” 6 As such, he was responsible for a major part of the decoration of the rooms. His invoice, also listed by room, itemizes the seaming of 456 yards of carpeting, hemming the enormous quantity of bed and table linen supplied by Bacon, and fashioning muslin curtains and silk drapery for sixteen windows, as well as curtains, mattresses, and pillows for the beds, for a total of $2286.89. Hedges’ workshop, too, must have worked nonstop.

The most elaborate room was the twenty by twenty-four foot drawing room on the first floor, where Lafayette greeted the public on the last full day of his visit. It was in this room that the couch, chairs, and the piano were placed along with a rosewood pier table and rosewood center table, both with marble tops. The crimson plush upholstery of the couch was complemented by Hedges’ crimson silk drapery and the “claret color” of the Brussels carpet. The drapery hung from cornices of “Burnishd Gold with rich Brass Ends,” and was trimmed with silk fringe, binding, and yellow “rope” or cord. A single muslin curtain at each of the ten-foot high windows was drawn to one side and held in place by a “Drapery Pin.” Hedges’ description that the drapery and curtains were “For four windows and pier” suggests that the cornice and drapery valance spanned two windows and the space between them (the pier) in a style called “continued drapery,” similar to the treatment illustrated in a plate of George Smith’s A Collection of Designs for Household Furniture and Interior Decoration (1808) and one that was popular in Boston at the time (Fig. 10).

|  | |

| Fig. 11: Gilbert Stuart (1755–1828), Portrait of James Monroe, 1822. Oil on canvas, H. 40¼ x W. 32 inches. Looking glass and frame maker John Doggett loaned the city portraits of the first five presidents that he commissioned from Gilbert Stuart, which included this image of Monroe, the fifth president. They hung on the walls of the main reception room in Lafayette’s lodgings where the couch and piano were located. After the event, Doggett charged the city for regilding the frames as well as repairing the looking glasses he had also loaned. Metropolitan Museum of Art (29.89). Image © the Metropolitan Museum of Art. | Fig. 12: Lit a Couronne (bed with wreath), plate 614, in Pierre de la Mésangère’s Collection de Meubles et Objets de Goût (Paris: Au Bureau du Journal des Dames et des Modes,1802–1831). The wreath supporting drapery seen in this plate is probably similar to the one supplied by upholsterer Thomas Hedges for the “French bed” made by Vose for Lafayette’s bed chamber. Several of de la Mésangère’s widely circulated designs were adapted by Vose for furniture he made in Boston. Courtesy of the Winterthur Library, Printed Books and Manuscripts Collection (NK2386 L22 F). |

|

| Fig. 13: French bed. Mahogany, Honduras mahogany, birch, ebonized maple (prob.), brass, steel, modern fabric. H. 47⅜, L. 84¾, D. 51¼ in. Isaac Vose & Son. The three French beds provided by Vose & Son for Lafayette’s lodgings probably resembled this example made for Rev. Francis Parkman in 1823 or 1824, after the birth of his first son, Francis Parkman Jr., who later became the noted Boston historian. Colonial Society of Massachusetts (17.1), gift of the great-grandchildren of Rev. Francis Parkman. Photo by David Bohl. |

The room was lit by the hanging cut-glass center lamp and two pairs of gilt argand lamps “lent” by Vose, and further appointed with white and gold porcelain vases with landscape views and an “alabaster Paris Time Piece.” Eliza Susan Quincy, who served as a kind of secretary for her father, the mayor, and kept a journal detailing the week’s events, wrote that the walls were “ornamented with the portraits of the five Presidents by Stuart.” 7 These were the set that John Doggett had commissioned from Gilbert Stuart in 1822 and which later served as the source for his lithographic series “The American Kings.” 8 What more appropriate to display in this room than images of the men who led the new nation whose freedom Lafayette helped secure, many of whom he knew well and would visit later on his journey (Fig. 11). John Doggett also provided, with a minimal down payment, two pairs of looking glasses, the most expensive of which, valued at $425, was probably used in this room. One would have been placed between the windows on the wall with the continued drapery and the other used as a chimney glass above the mantel. They are further described in the auction notice as “1 pair of Looking Glasses, French plates, rich black and gold reeded frames.”

| |

| Fig. 14: Abel Bowen and William Hoogland, engraving of Lafayette inscribed, “Honor to the Brave/ LAFAYETTE,” 1824. Eliza Susan Quincy pasted this dinner party souvenir into the journal she kept of Lafayette’s visit to Boston. Collection of the Massachusetts Historical Society (Ms. N-764, QP-44, p. 42). |

Doggett’s second pair of looking glasses was used in the drawing room directly above on the second floor. In this room, Hedges used yellow silk drapery for the windows, providing a stylish contrast with the black horsehair upholstery of the two mahogany sofas and twelve chairs. Here the silk was draped over large carved and gilded wreaths and corner ornaments at each window. Hedges provided the same treatment for the window in the bedchamber across the hall, presumably the one used by Lafayette, and no doubt where Vose’s expensive “French Bedstead with Gilt Ornaments” was installed. The bed was probably similar to the one illustrated in Pierre de la Mésangère’s published plate “Lit à Couronne,” (bed with wreath) (Fig. 12). The gilt and carved wreath used to suspend the principal drapery depicted in the print corresponds to Thomas Hedges’ charge for a “Large Carved Reath [sic] in Burnishd Gold.” At least five surviving beds similar to this French design are attributable to the Vose & Son shop, including those owned by Boston merchant Charles Russell Codman, Daniel Webster, Nathan Appleton, and Rev. Francis Parkman (Fig. 13), and a fifth with no family history. None of these survives with an accompanying carved wreath. Two less expensive French beds, draped with blue silk to match the window curtains, were in the rooms on the third floor that were intended for Lafayette’s son, George Washington Lafayette, and his secretary Auguste Levasseur.

Eliza Susan Quincy recorded in detail the public events and speeches, as well as more intimate details of Lafayette’s private visits with friends and conversations at parties and dinners. At one dinner given by George Ticknor, a likeness of Lafayette printed on red paper was placed under a glass at each place at the table (Fig. 14), which the guests later pinned to their clothing. Lafayette then bowed to them and said, “You are all very good to me. I am very much obliged to you.” 9 Being the documentarian that she was, Eliza pasted hers into her journal, thus preserving a small but unique souvenir of a grand event in Boston’s history.

Isaac Vose & Son’s furniture formed an integral part of the episode that Eliza rhapsodized about in her diary, “The whole of the scene, was the height of the moral sublime, such a country, such a people, such a man, and such a reception, are unparalleled in the history of the world.” 10

Entrepreneurship and Classical Design in Boston’s South End: The Furniture of Isaac Vose and Thomas Seymour, 1815 to 1825, the first exhibit dedicated to Vose’s furniture, will be on view at Massachusetts Historical Society, 1154 Boylston Street, Boston, Mass., May 11–Sept. 15, 2018. A catalogue titled Rather Elegant Than Showy: The Classical Furniture of Isaac Vose, with 340 illustrations, accompanies the exhibit.

Robert D. Mussey, Jr. is an independent furniture scholar and a retired furniture conservator in Milton, Mass. He is author of The Furniture Masterworks of John & Thomas Seymour. Richard C. Nylander is curator emeritus, Historic New England.

This article was originally published in the Summer 2018 issue of Antiques & Fine Art magazine, a fully digitized edition of which is available at afamag.com. AFA is affiliated with Incollect.

2. City of Boston Archives, West Roxbury, Mass.

3. The house was occupied by a group of Boston gentlemen who comprised the Bunker Hill Monument Association founded in 1823 to raise money to build a lasting memorial to the famous early battle of the Revolution. Membership required “subscribing” a donation of money, thus the name, “Subscription House.” Members saw Lafayette’s visit as an ideal opportunity to solicit additional donations for their cause, hence their offer of the house for his lodging there.

4. Vose & Son also imported lighting from England and France, as well as gilt looking glasses, furniture hardware “ornaments,” furnishing textiles, and drapery patterns.

5. No parallel furniture rental for any other Boston event is known to the authors. According to furniture scholar Peter Kenny, the city of New York rented from various New York makers and furnishing suppliers for the 1834 visit of President Andrew Jackson and Vice President Martin Van Buren in June 1833. See the subsequent auction advertisement in New York Commercial Advertiser, June 17, 1833.

6. Boston Daily Advertiser, March 20, 1824, and numerous later dates.

7. Eliza Susan Quincy, “Journal of Lafayette’s Visit, 1824-1825,” 42. Quincy Family Papers, Ms. N-764, QP-44, Massachusetts Historical Society.

8. Doggett announced in an ad in the November 16, 1825, issue of Boston’s Columbian Centinel, the arrival in Boston from France of the lithographic plates for the “Portraits of the Presidents,” and that they had “adorned the residence of the Nation’s Guest during his visit to this city.”

9. Quincy, “Journal,” 42.

10. Quincy, “Journal,” 34.