Working Like a Dog

The superb sporting art collection of John L. Wehle, founder of the Genesee Country Village and Museum in Mumford, New York, forms the core of an exhibition at the Pebble Hill Plantation in Thomasville, Georgia. The loan exhibition incorporates important pieces from Pebble Hill’s permanent collection and historical archives that explore the unique partnership between humans and canines over time. It is the second exhibition and collaboration between these two museums that house the best collections of sporting paintings of their kind.

|

Francis Barlow (England, 1626–1704), The Game Larder, 1672. Oil on canvas, 43 x 54 ½ inches. |

In 1672, English artist Francis Barlow painted this canvas, perhaps a commissioned portrait of an aristocrat’s favorite hunting dogs, and definitely a compelling work, both artistically and historically. The artist shows us the interior of a game larder, enlivened with a diagonal swath of golden light streaming from left to right, dividing the composition in half. At center, united by color and light, hangs a hare, nuzzled by the very greyhound that brought it to is current state.

At upper right hangs a mallard duck and a bustard, a large land bird so popular in England in the seventeenth century that it was almost hunted to extinction. Punctuating this composition with a splash of scarlet is a live squawking cockerel not best pleased with his situation. On the table lie woodcock and pigeons, probably retrieved by the spaniels whose softly rendered forms form one side of the work’s triangular composition. Barlow was well acquainted with Dutch still life and incorporated the classical stone table and wheat stalks that were stock motifs of that genre. There is a Baroque sense of balance to this work that portrays birds that inhabit the earth (bustard and cockerel), birds that inhabit the water (mallard and woodcock), and those that inhabit the air (pigeons).

Barlow painted this work one year after the Game Act of 1671 was passed, prohibiting persons from hunting game unless they owned a freehold on land with a yearly value of one hundred pounds or held a ninety-nine-year lease on land that had a yearly value of 150 pounds. The Game Act also prohibited all but the landed gentry from owning guns — and hunting dogs, specifically greyhounds, “setting dogs,” “retrieving dogs,” or dogs that might be used for poaching. Not surprisingly, a well-bred retriever was relatively expensive, costing about five pounds, the equivalent of the wages a skilled carpenter would have earned in four-and-a-half months.

With its hunting dogs and abundance of game, this painting was an unabashed statement of wealth and entitlement. Implied in this work is the rich fare that such game provided. Cookbooks of the time, generally limited to the wealthy, specify receipts for hare pie, spiced with nutmegs, mallards stuffed with dates, sauced with wine and spices, and served up on platters rimmed with sugar — all expensive imported items. Less distinguished folk purchased game and meat from markets or raised domesticated ducks, geese, and rabbits. At the time this painting was created, letters from America, intent on luring settlers to the New World, repeat a common theme: that the American woods and fields teamed with game and that everyone there ate game and meat in abundance.

|

Nelson Cook (1809–1892), An American Sportsman, Millard Powers Fillmore, 1850. Oil on bed ticking, 79 x 56 ½ inches. |

Nelson Cook, a Canadian-born artist who traveled between Buffalo and Saratoga Springs, New York, created this full-length likeness of Millard Powers Fillmore, known as “Powers.” The son of Millard Fillmore, the thirteenth President of the United States, he studied law at Harvard and then served as his father’s secretary during his presidential administration.

The sheer size of the work was meant to impress, particularly at a time when the prosperous usually commissioned only a half-portrait that showed the subject from waist to crown. One of only three life-sized portraits by Cook, the Fillmore portrait was designed to occupy a significant spot in an equally significant house.

With its background landscape that depicts Dunkirk, New York, and Lake Erie, this work emulates the grand manner of European and British portraiture. The figure of Powers glances to the viewer’s right and is placed high, so he literally looks down and away from the viewer, creating both a deliberate physical and physiological distance from the viewer.

Powers leans on his double-barreled percussion cap shotgun in a casual, proprietorial pose, flanked by his trusty gun dog. He wears what was then known as “genteel undress,” meaning informal wear. This included an unbuttoned tartan frock coat popularized by Prince Albert, husband of Queen Victoria, himself an avid hunter, and the button fly trousers that became fashionable in the mid-1840s. Contributing to his more casual attire, Powers wears a loosely knotted neckerchief and a broad brimmed Panama straw hat. The subject also sports a glass powder horn to keep his gun powder dry, perhaps made in the Pittsburg, Pennsylvania, glasshouse, and a bandolier shot holder. To contemporary viewers, the portrait presented an ideal image of American manhood; the man who has a successful professional career but who yet retains the skills of the hunter.

|

Maud Earl (England, 1864–1943), Old Benchers, 1885. Oil on canvas, 50 x 71 inches. |

Born in England in 1864, Maud Earl first exhibited at London’s Royal Academy at the age of twenty. A year later, she painted Old Benchers, depicting foxhounds resting on their kennel bench. The title is a tongue-in-cheek reference to Britain’s senior barristers, called “the benchers,” who governed the Inns of Court.

Maud Earl was the daughter of notable sporting artist George Earl, who taught his daughter how to paint. This was typically the way women became professional artists at the time — by learning their art in the studios of their fathers, husbands, or brothers. Among other things, George Earl taught his daughter to draw skeletons of humans, horses, and dogs, to better understand anatomy. Maud Earl later reportedly claimed she became a successful canine artist because she could paint a dog from the inside out. Earl liked dogs and was able to capture the true character of her canine subjects because she made a point of spending time with them to learn their “little likes and dislikes” before she began painting them. Earl’s approach to her subjects reflected a more humane view of animals, particularly dogs, brought about by the founding of humane societies.

Consequently, her paintings were portraits that captured the naturalism, vitality, and spontaneity of her subjects.

Her first commissions came from the world of purebred dog shows, but as her reputation grew, she became a favorite of Queen Victoria, King Edward VIII, and other British notables. After World War I, Earl moved to New York, where she continued to paint until her death.

|

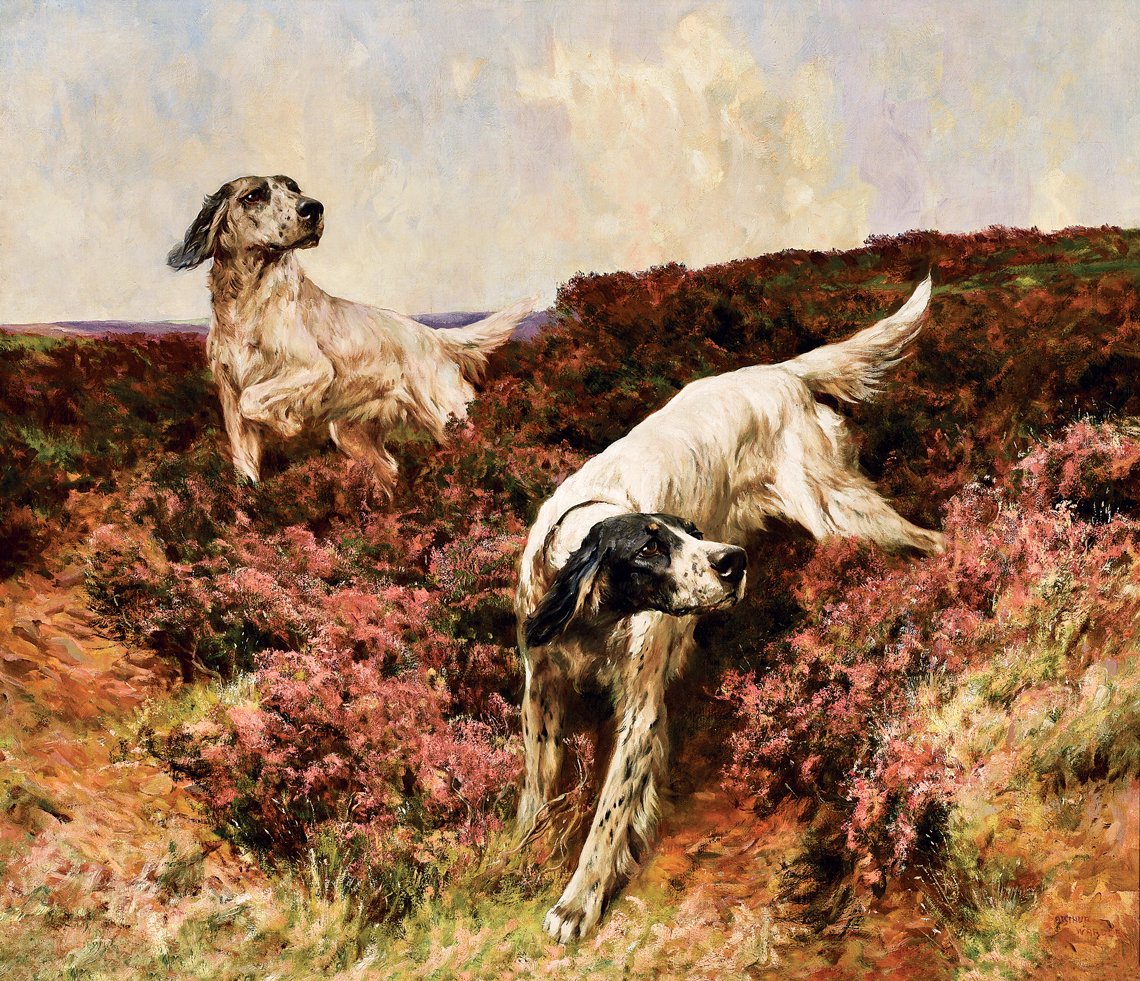

Arthur Wardle (England, 1860–1949), Setters on a Heather Covered Heath, ca. 1895. Oil on canvas, 32 ½ x 38 ½ inches. |

Arthur Wardle was one of the most renowned English dog painters, although he also painted other animals. Largely self-taught, at an early age he became an accomplished artist and a member of the Royal British Colonial Society of Artists, the Pastel Society, and the Royal Institute for Painters in Watercolor. His works were so popular that they were reproduced in his time on postcards, calendars, biscuit tins, and chocolate boxes.

To the untrained eye, this painting may appear to present two setters scampering through heather. The experienced sportsman, however, recognizes exactly what’s taking place. Long and lean, the setters silently track for game birds whose scent is borne on the air. Once they scent the game, the setters freeze, with head oriented in the direction of the game and tail level with their back; they assume the “set.” To clearly portray the dogs’ athletic qualities, as well as a sense of motion, Wardle used diagonal lines throughout his composition. A true portraitist, Wardle has captured the individual expressions of the dogs.

|

Arthur Wardle (England, 1864–1949), A Jack Russell Terrier, ca. 1900. Oil on canvas, 26 x 26 inches. |

In this painting, Wardle poses the dog to show off its specific breed characteristics and conformation. The Jack Russell Terrier originated in England, from dogs bred by the Reverend John Russell in the early nineteenth century. It has similar origins to the modern fox terrier, originally bred for foxhunting, although the Jack Russell, with its long straight front legs, tended to be larger than the terriers that more easily burrowed into fox holes. The dog’s wiry coat comes through the brushstroke, beautifully set against the autumnal tones of the undergrowth.

|

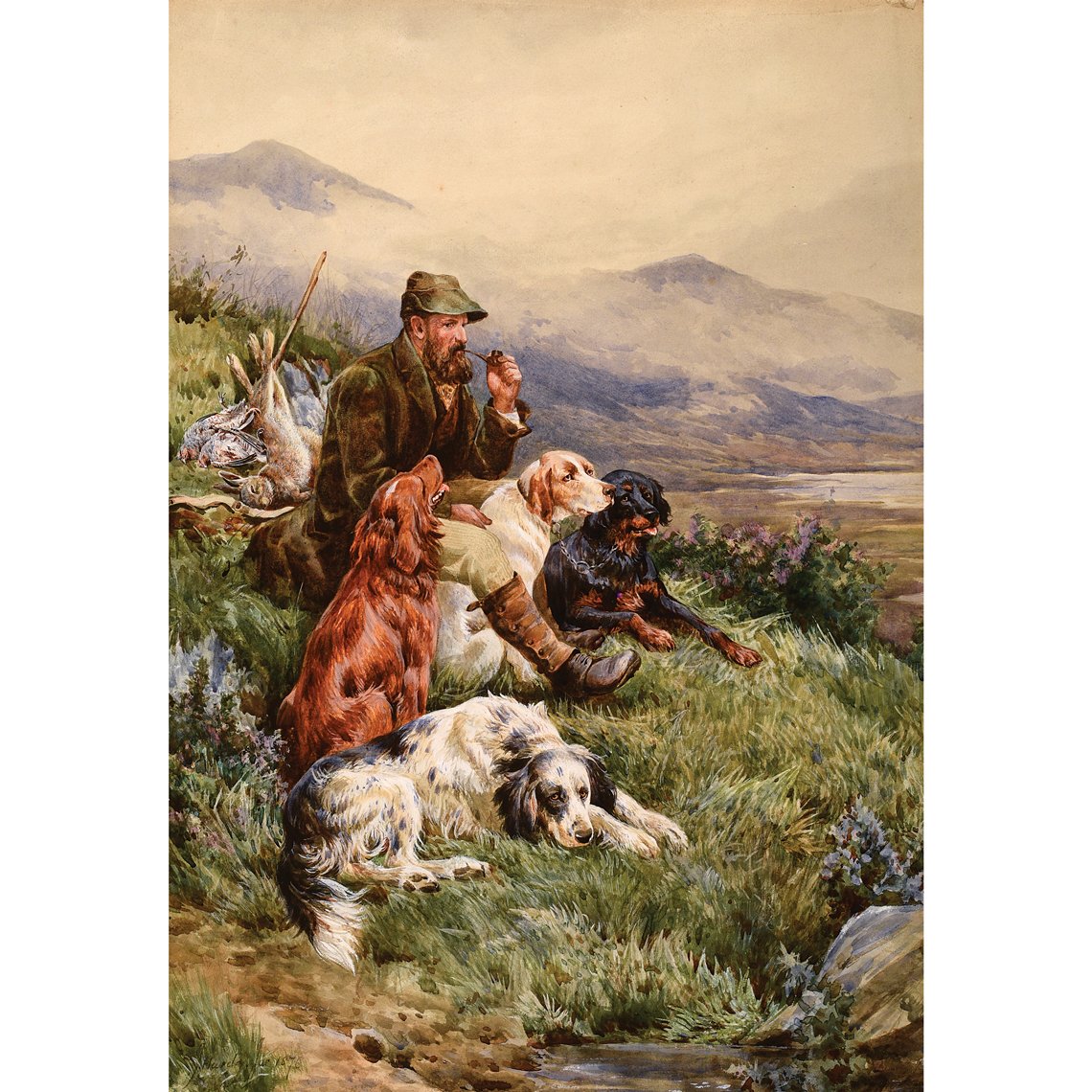

James Hardy Jr. (1832–1889), English, The End of a Day’s Sport, 1876. Watercolor on paper, 37 x 28 inches. |

Born in 1832, James Hardy Jr. came from a family of painters. His father specialized in landscape, and that influence can be seen in the sensitive handling of the Scottish hills in this work. James Hardy Jr. frequently depicted the Scottish highlands made so popular by Queen Victoria and Prince Albert, who prized its wilderness and game, much the way the Adirondacks were celebrated in the U.S.

Hardy usually painted in oil, but was adept at watercolors, as shown by this highly detailed work. This work provides a glimpse into the bond between hunter and hunting dogs, resting after a long day in the field. Arranged from bottom to top are an English Setter, a Red Irish Setter, an English Pointer, and a dark brown Gordon Setter. Hardy often included Gordon Setters in his paintings, perhaps because the dark color makes a pleasing contrast to the other dogs. These breeds became great favorites as general hunting dogs, and were used for hunting various game birds throughout the British Isles. The Kennel Club applied the name Gordon Setter to the breed in 1924. Before that they were known as Black and Tan Setters and were found in many kennels besides those of Alexander Gordon (1743–1827), fourth Duke of Gordon, for whom they were named.

|

Percival Rosseau (1859–1937), Setter in an Open Field, 1929. Oil on canvas, 26 x 33 ½ inches. |

Perceval Rosseau’s life reads like an action adventure. Born in Louisiana on a plantation later destroyed by General Sherman, Rosseau was orphaned during the Civil War. A former slave took Rosseau and his sister to family friends in Kentucky, who raised the pair. Rosseau learned to hunt and shoot in the Kentucky hills and fields, but when he demonstrated artistic abilities, his guardians sent him to a private school, where he studied drawing. Around the age of eighteen, Rosseau headed west, where he worked as a cowboy and cattle drover on the Chisholm Trail. He later became a successful import broker in New Orleans and New York. At the age of thirty-five, he moved with his family to Paris to study art at the Académie Julian. There he fell under the spell of the Barbizon School, artists who painted directly from nature, focusing on rural landscapes and preindustrial subjects.

In 1904, the artist submitted two paintings of setters in landscapes to the Paris Salon. “The day after the Salon opened I received eleven telegrams asking my prices for the pictures,” the artist recalled, “and I sold both in a few hours. Thereafter I had little trouble selling my work.” 1 From that point on, Rosseau devoted himself almost entirely to the painting of dogs, becoming the premier American dog painter.

Rosseau continued to work in this style upon his return to the U.S., finding inspiration from the Sullivan County, New York, landscape and the hills of North Carolina. Painting only sporting dogs, Rosseau infused his canvases with a soft light and atmosphere. He captures the essence of a sporting dog in the field yet maintains the beauty and vastness of the landscape as well. “A man should paint what he knows best,” Percival Rosseau wrote “and I know more about animals then [sic] anything else. I have run hounds from childhood, and have at my fingertips the thorough knowledge of dogs necessary to paint them faithfully.” 2

1. William Secord, A Breed Apart (Woodbridge, Suffolk, 2001), 128.

2. Ibid.

Working Like a Dog, is on view at Pebble Hill Plantation, Thomasville, Georgia, through April 25, 2019. It will return to the John L. Wehle Gallery, at the Genesee Village and Museum in Mumford, New York, where it will be on view from May 11 through Columbus Day, 2019. For more information visit www.pebblehill.com or www.gcv.org.

Patricia Tice is curator of the John L. Wehle Gallery, Mumford, New York.

This article was originally published in the Summer 2019 issue of Antiques & Fine Art magazine, a fully digitized version of which is available at www.afamag.com. AFA is affiliated with Incollect.com.

All images from the collection of the Genesee Country Village and Museum.