Rembrandt and Printmaking in the Netherlands

|

|

embrandt van Rijn was among the greatest innovators in the history of art, producing masterpieces of painting, draftsmanship, and printmaking. He approached each medium independently, revolutionizing all three. While nearly unthinkable to consider, had he never created a painting, Rembrandt—like Leonardo or Goya—would still be considered among history’s greatest artists.

Rembrandt is best known for his enormous group portrait, the Night Watch at the Rijksmuseum, painted in 1642. However, during his lifetime, Rembrandt’s fame rested on his prints, which reached audiences all over Europe.

As a printmaker, Rembrandt primarily used etching, a medium in which drawn lines are bitten into a waxed copper plate with acid. With the exception of several prints made in the early 1630s, Rembrandt did not use prints to reproduce his paintings. Rembrandt often added design in drypoint, using a needle to gouge out lines, to add depth and rich blacks to the impression, as is most evident in the night pieces. He constantly made changes to the plates and experimented with his medium, resulting in different versions, called “states.” He delighted in intentional accidents by disrupting the acid process, producing unprecedented effects of darkness and shadow. He also tried different papers, including imported Asian varieties, each of which changed the light and tone of the image. Each of his prints, then, is an entirely unique work of art.

The San Diego Museum of Art shares the extraordinary artistic accomplishment of Rembrandt and seventeenth-century painters and printmakers from the Dutch Republic in Rembrandt and Printmaking in the Netherlands, an exhibition including approximately twenty etchings and engravings by Rembrandt from the museum’s permanent collection and on loan from the important Rembrandt collection of the University of San Diego (USD). The exhibition is now on view at The San Diego Museum of Art. For information, visit sdmart.org or call 619.232.7931.

|

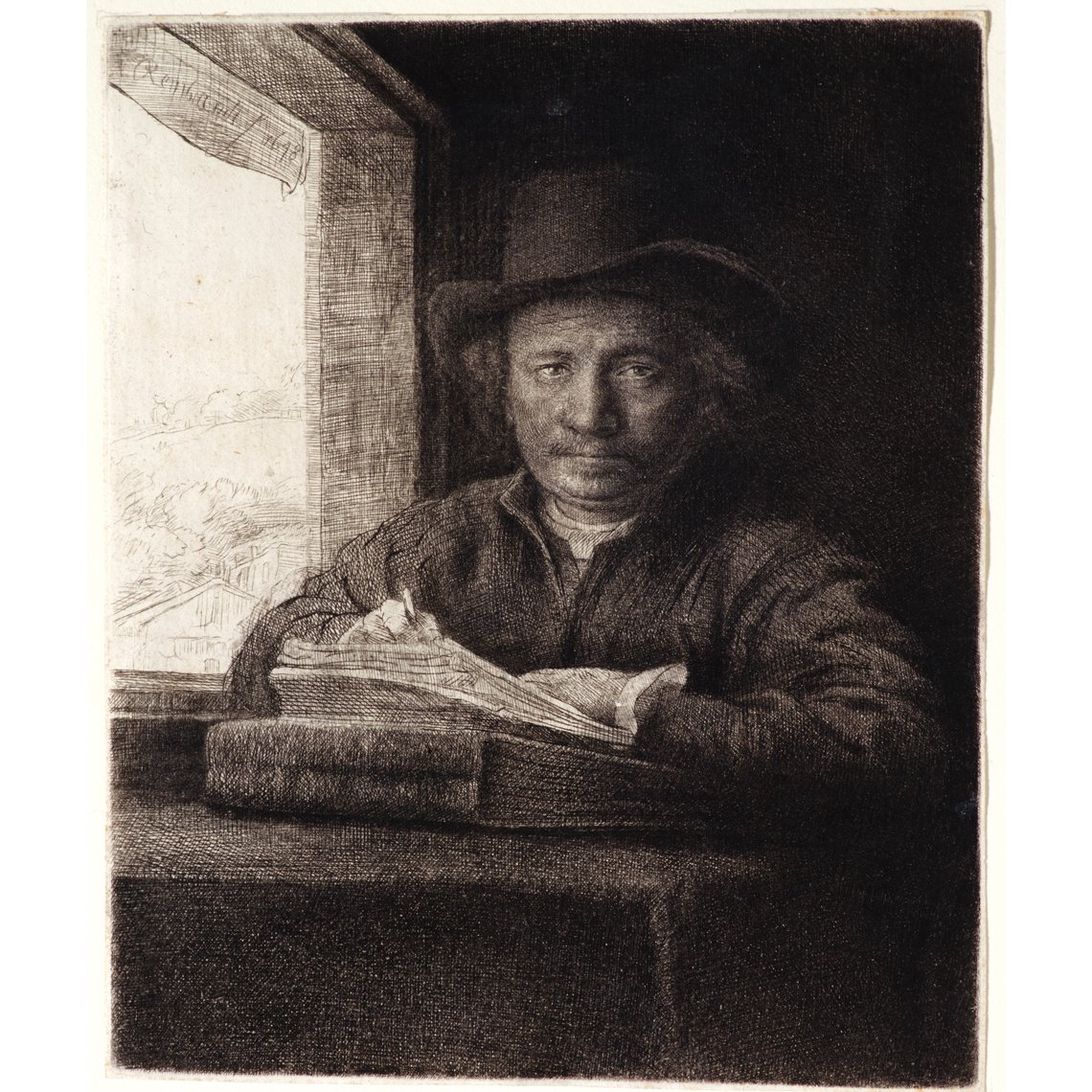

Rembrandt Harmensz van Rijn, 1606–1669, Self-portrait Etching at a Window, 1648. Etching, drypoint, and burin on laid paper. Museum purchase with funds provided by Helen M. Towle Bequest (1947.64.d). |

While self-portraits were a significant part of his output throughout Rembrandt’s career, this is the first in etching after a decade-long hiatus. This is the fourth (and final by Rembrandt’s hand) state of the print, meaning Rembrandt made significant changes in each of the previous three states. We find here an introspective master, at work on an etching plate with drypoint needle in hand as sunlight illuminates his activity yet leaves his face in dramatic shadow. Rembrandt’s technique and psychological insight make this

his most enduring self-portrait etching.

|

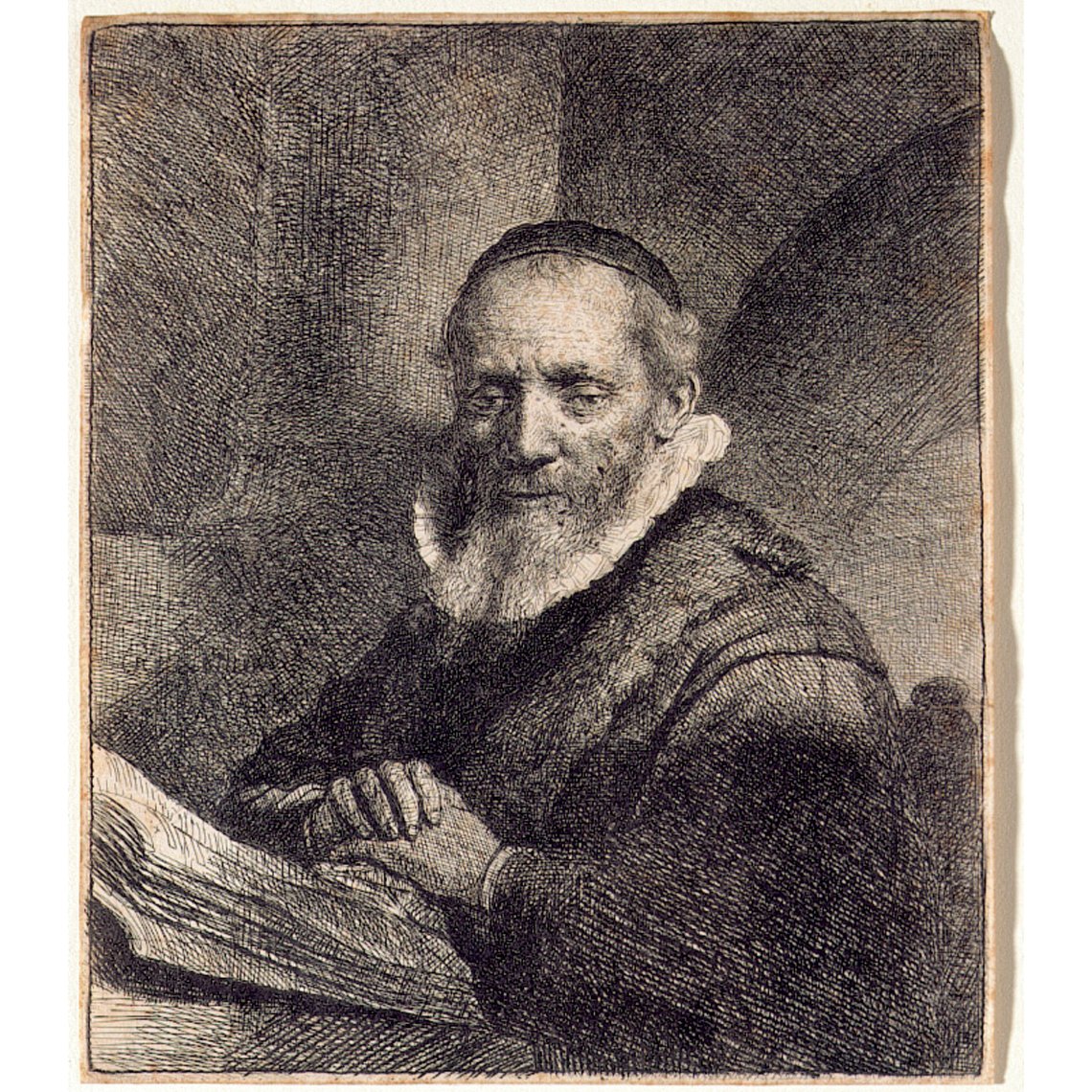

Rembrandt Harmensz van Rijn. Rembrandt’s Mother with Her Hand on Her Chest: Small Bust, 1631. Etching. Gift of Mrs. Irving T. Snyder (1952.39). This image was conserved for the exhibition. |

Rembrandt first began etching in late 1626, while living in Leiden and working alongside Jan Lievens (1607–1674), a fellow student of Pieter Lastman. Both Lievens and Rembrandt experimented with familiar and everyday subjects, including head studies known as “tronies.” This early etching shows Rembrandt’s interest in printmaking as an independent art form, in this case lending its medium brilliantly to the depiction of his mother’s craggy features.

|

Rembrandt Harmensz van Rijn. Jan Cornelisz Sylvius, Preacher, 1633. Etching on laid paper. Museum purchase with funds provided by the Helen M. Towle Bequest (1947.64.b). |

Most of Rembrandt’s early subjects were friends and family, including Jan Sylvius, the guardian of the artist’s wife, Saskia van Uylenburgh. Here the sitter crosses his hands on his Bible, seated in a chapel-like space while the architecture flickers between light and shade. This etching is also known in multiple states, with Rembrandt making changes at some point by taking a counterproof (a transfer of wet ink from one paper sheet to another) and making corrections in black chalk (now in the British Museum).

|

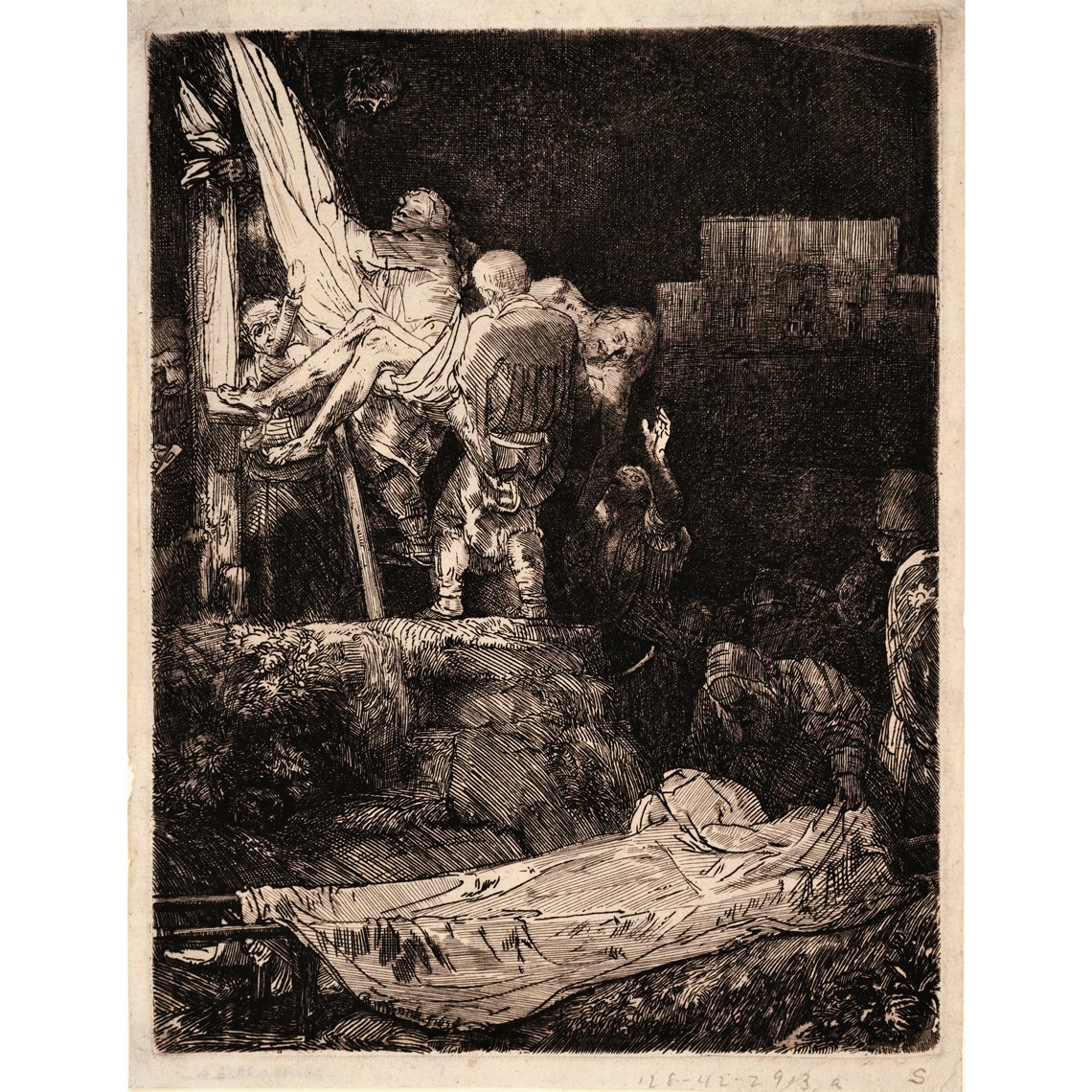

Rembrandt Harmensz van Rijn, Descent from the Cross by Torchlight, 1654. Etching. Collection University of San Diego. Gift of Robert and Karen Hoehn (PC2004.01.05). |

Rembrandt was particularly fascinated by the human aspects of Bible stories, as well as with the Jewish community in Amsterdam. Here he depicts a Jesus driven by righteous anger, overturning the tables on which foreign currencies were exchanged at unfair rates. As he does so, he quotes the Old Testament prophet Jeremiah, who condemned those who had turned the “house of prayer for all the nations,” into a “den of robbers.” His actions were not, however, a condemnation of the temple itself, as Jesus took care not to disturb the holy coffers, casting out only those who were breaking Jewish law.

|

Rembrandt Harmensz van Rijn, Christ Driving the Moneychangers from the Temple, 1635. Etching and drypoint. Collection University of San Diego; Gift of Robert and Karen Hoehn (PC2004.01.03). |

Rembrandt’s creative genius comes through in this small work, not merely reflected in his choice to set it at night, but also the focus on the human emotions and physical efforts of Joseph of Arimathea and the disciples. The cross is not fully visible, but the excruciating detail of one foot still attached by nail is balanced by the gentle poetry of the single illuminated hand reaching up to help.

Michael Brown, Ph.D., is curator of European Art, The San Diego Museum of Art, San Diego, Calif.

This article was originally published in the Winter 2020 issue of Antiques & Fine Art magazine, a fully digitized version of which is available at www.afamag.com. AFA is affiliated with Incollect.com.

|