A Bright Future for Southern Decorative Arts: MESDA’s 50th!

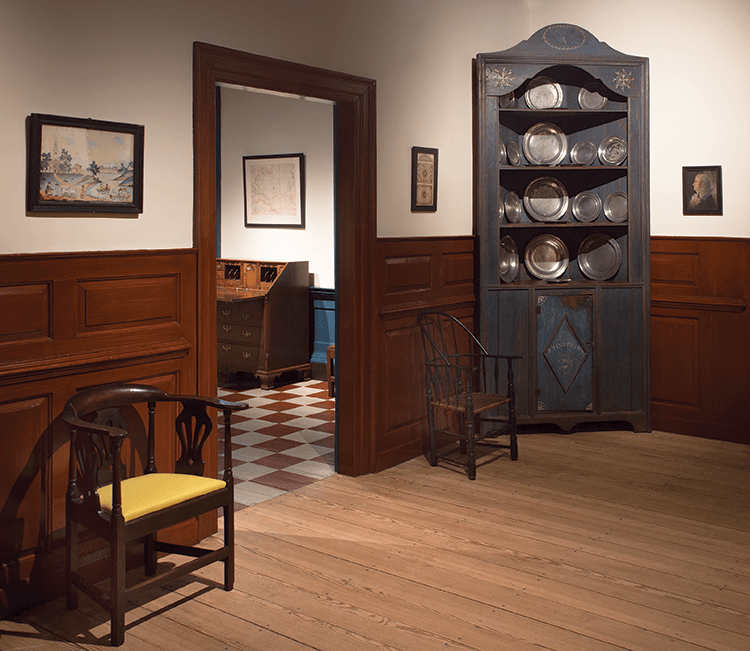

Founded in 1965 by the legendary scholar and collector Frank L. Horton, the Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts (MESDA) in Winston-Salem, North Carolina, is completing an eight-year plan to prepare the museum and its collection for the next fifty years. The museum’s wallpapers and window curtains, once state-of-the-art period-room installations, had faded; the paint, once fresh, had dulled; and a fluorescent lighting system from the 1970s did not do justice to the museum’s collections. By 2008—when the eight-year renovation plan was launched—it was high time to give MESDA a curatorial facelift (Figs. 1, 2).

To accomplish the multi-year, multi-step endeavor, we assembled a team of recognized experts from across the southeast to help replace worn-out fabrics, repaint rooms according to the best historic evidence, and—most importantly—to make the public experience brighter and more colorful. The results have been dramatic.

First we selected an adjustable track lighting system to accommodate a variety of object placements in gallery arrangements, and one that could be installed one room at a time as the individual gallery renovations progressed. Object sensitive, with motion sensors that turn lights on when public tours are in progress, collections return to almost storage-like conditions when a gallery is empty.

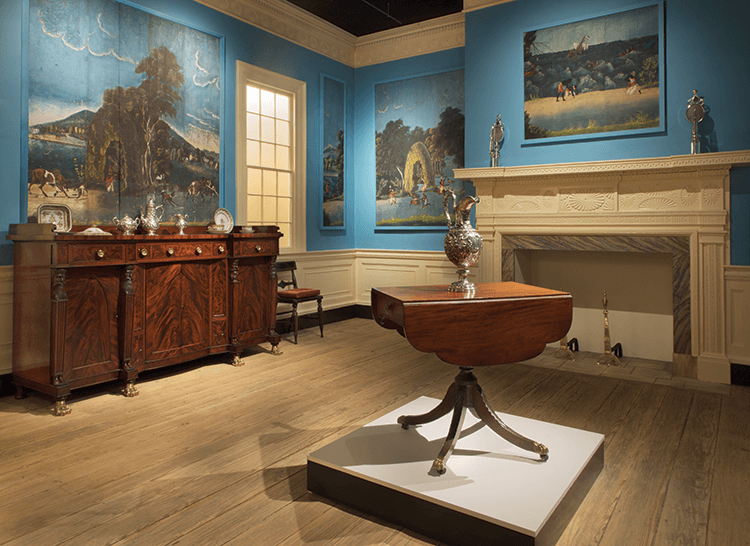

- Fig. 8: The blue damask curtains that Natalie Larson selected for the Charleston Parlor is a fabric that MESDA’s curators also chose when Leroy Graves upholstered the Baker family easy chair (pictured front left) and again for the base of the gallery’s exhibit of silver made by the Charleston silversmith Alexander Petrie.

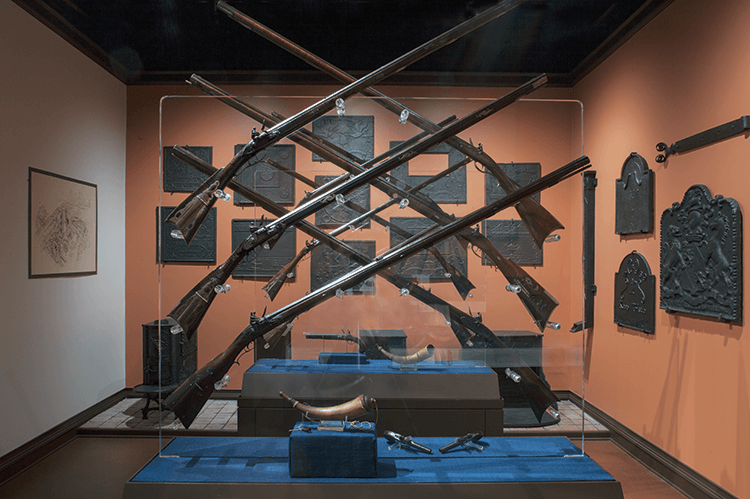

With new lighting came new paint colors. Interior designer Ralph Harvard, a member of MESDA’s advisory board and whose passion for early Southern decorative arts and architecture is legendary, created a lively palette of vibrant blues, reds, oranges, greens, and yellows for the museum’s non-historic galleries (Figs. 3, 4). In some cases, the gallery colors were based on authentic historic prototypes, such as the turquoise blue selected for the Charleston Neoclassical Gallery (Fig. 5) that copies the very shade on wallpaper installed in 1808 in the Nathaniel Russell House dining room in Charleston.

By 2009, the historic paint evidence for MESDA’s period rooms was ready for implementation. Carefully testing each period room, Susan Buck, one of the nation’s leading historic paint analysts, identified their original color. For example, the Pocomoke Hall had been painted in 1965 with a combination of red and blue (Fig. 6); however, Susan’s analysis revealed that in the eighteenth century, when the house was first built for the Powell family on the Eastern Shore of Maryland, the room had indeed been painted red, but it had also been blue. Susan determined, however, that it was never both red and blue at the same time. MESDA curators returned the room to its original, circa-1730 shade of bold red (Fig. 7).

These historically accurate paint colors called for equally appropriate textiles for furniture upholstery and window treatments. Colonial Williamsburg upholstery conservator Leroy Graves and independent textile historian Natalie Larson helped MESDA select and install fabrics on objects, using the latest and best historical research. Under Natalie’s supervision, window frames, easy chairs, back stools, and slip seats came to life with vibrant new colors and patterns from historically accurate reproduction textiles (Fig. 8). A pioneer in non-invasive upholstery conservation treatments, Leroy Graves completed a number of upholstery projects, including a pair of rare, Virginia-made eighteenth-century backstools (Fig. 9) and an eighteenth-century Charleston easy chair that descended in the Baker family of Archdale Hall Plantation (see figure 8).

For historically accurate wallpaper in the Courtland Parlor (Fig. 10), Colonial Williamsburg curator and MESDA Advisory Board member Margaret Pritchard selected a geometric-patterned paper. Originally from a house built around 1810 for the Ricks family in Southampton County, Virginia, the paper was firmly documented as sold in the early nineteenth century. Adelphi Paper Hangings reproduced the paper, with a matching border, and Margaret supervised its installation to insure that every seam was perfect.

One of the most exciting projects has been the White Hall Dining Room (Fig. 11). This dramatic room features hand-carved woodwork from a Porcher family plantation that once stood in Lowcountry South Carolina. Its elaborate gougework was probably executed by an as-yet-unidentified enslaved craftsman and relates to a small body of work only found in that region at plantation houses associated with the Porcher family. The room also features one of MESDA’s most important objects: the original hand-painted scenic wallpaper that once graced an 1840s plantation house belonging to the Snowden Griffin family in Columbia County, Georgia, outside of Augusta. Before the Griffin House was demolished in the 1930s, the paper was saved by the late Dewitt and Ralph Hanes and used in their Winston-Salem house, then generously given to the museum in the 1970s. With a grant from the Richard C. von Hess Foundation, the room has been conserved with museum-quality lighting and historically accurate paint on the carved woodwork, providing a perfect backdrop to the newly conserved Georgia wallpaper’s fanciful scenery.

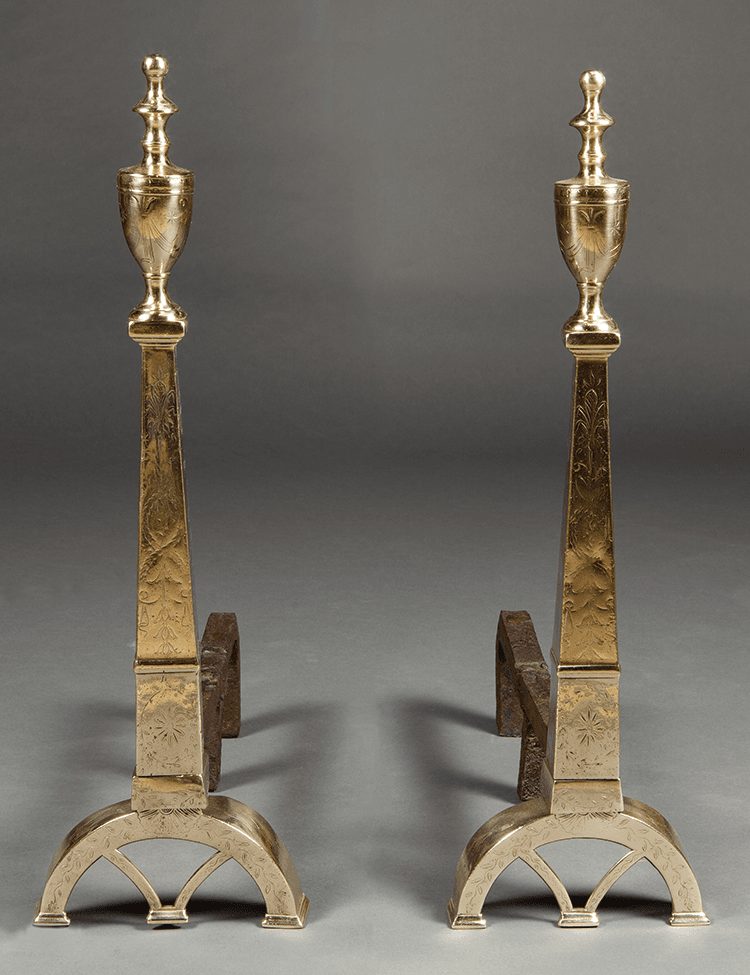

Other exciting conservation projects include Al Crabtree’s work on a pair of circa-1790 engraved brass andirons (Fig. 12) that descended in the Ford family of Rice Hope Plantation in Georgetown County, South Carolina. They are part of a large group of Charleston-related andirons that was first published in 1979 by Brad Rauschenberg in MESDA’s scholarly periodical, the Journal of Early Southern Decorative Arts.

In 2012, cabinetmaker and conservator Martin O’Brien undertook the full-scale restoration of a circa-1730 turned chair that had descended in the Goldsborough family of Talbot County, Maryland. Like many early turned chairs, this one had been cut down in size and rockers added. Martin removed the rockers, exposing the evidence for a third row of original turned stretchers. Martin also conserved a significant desk and bookcase (Fig. 13) made in Norfolk, Virginia, around 1760, and signed by the cabinetmaker Robert Wilkins. It is the most recent addition to MESDA’s important collection of signed southern furniture.

After eight years—and in time for its 50th anniversary celebrations this October—MESDA is poised to complete all thirty of its gallery renovations in order to create a museum experience that meets the needs of modern audiences in new ways. Our visitors can now select tours that match their interest levels as well as their schedules, with general-interest tour options that last 45 minutes, an hour, or even two hours as well as longer study tours focused on specific topics, such as the lives of early southern women or the role of enslaved African-American craftsmen in early southern decorative arts and material culture. Individually customized tours, booked in advance, are also available, allowing MESDA’s visitors to experience and explore only the rooms and objects that reflect their own particular interests.

For information on MESDA’s 50th anniversary celebrations from October 23–24, visit www.oldsalem.org/MESDA50.

Robert A. Leath is chief curator and vice president of collections and research at Old Salem and MESDA, Winston-Salem, N.C.

MESDA More Accurate and More Beautiful

MESDA has relied on a talented team of experts to complete the museum’s gallery renovations. Each is recognized as among the very top in his or her field.

|

|

This article was originally published in the Autumn 2015 issue of Antiques & Fine Art magazine, a digitized version of which is available on afamag.com. Antiques & Fine Art and AFAmag are affiliated with InCollect.com.