A Colorful Folk: Pennsylvania Germans and the Art of Everyday Life

The Pennsylvania Germans have long been renowned for their tremendously diverse, colorful, and often whimsical folk art (Fig. 1). Also known as the Pennsylvania Dutch, they descend from the approximately 80,000 German-speaking people who had immigrated to Pennsylvania by 1775 and who made up about 40 percent of the population in the southeastern part of the state by 1790. About 90 percent of these German-speaking immigrants were from the Palatinate region of southwest Germany and belonged to the Lutheran or Reformed Church. The remaining 10 percent consisted of sectarian groups, including the Amish and Mennonites, largely from the German-speaking cantons of Switzerland; Schwenkfelders, from Silesia (part of modern-day Poland); and Moravians, primarily from Bohemia and Moravia. Most Pennsylvania Germans inhabited the counties of Berks, Lancaster, Lebanon, Lehigh, Montgomery, Northampton, Northumberland, and York, but a sizeable number lived in Philadelphia. In 1800, people of German heritage vied with those of English ancestry as the largest ethnic group in the city, with both populations estimated at 32 to 35 percent of the total 68,000 residents.

Winterthur Museum is one of the leading institutions for the study of Pennsylvania German folk art, due in large part to the legacies of Henry Francis du Pont (1880–1969), who opened Winterthur to the public as a museum in 1951, and Frederick Sheely Weiser (1935–2009). Today, more than a dozen rooms at Winterthur are furnished with Pennsylvania German architecture and decorative arts. Among the most notable is the Fraktur Room, with its vibrant painted woodwork (Fig. 2). Weiser was a Lutheran minister, scholar, and collector of Pennsylvania German antiques, with which he furnished his home, known as Parrehof or “preacher’s farm.” Following his death in 2009, Winterthur acquired 121 fraktur and nearly 200 textiles from his estate—many of which are featured in the museum’s new exhibition A Colorful Folk: Pennsylvania Germans & the Art of Everyday Life. Twelve private collectors and institutions also loaned important works of art to the show, the first comprehensive exhibition of its type in more than three decades. Under the themes of home, church, school, and nation, the exhibition explores the unique world of the Pennsylvania Germans through their decorated manuscripts (fraktur), textiles, metalwork, pottery, and furniture (Fig. 3). Most objects are functional, but others were made “just for nice” and attest to the Pennsylvania Germans’ penchant for decorating virtually everything—from a tiny pincushion to the side of a barn.

- Fig. 3: Chest for Johannes Miller, decoration attributed to Henrich Otto (1733–ca. 1799), Millbach area, Lebanon County, Pa., 1783. Tulip-poplar, iron, paint, H. 23⅛, W. 49¾, D. 22⅛ inches. Private collection. Photography by Gavin Ashworth.

Careful study of the decoration and lettering on this recently discovered chest reveals that it was decorated by noted fraktur artist Henrich Otto. The two camels on the front are unique, but the flowers and a pair of parrots on the lid relate directly to examples of Otto’s fraktur.

HOME

The center of activity in a Pennsylvania German household was the Stube (stove room). Here the family dined and did sewing, spinning, and other daily tasks. In the mid-1700s, most Pennsylvania Germans heated their houses with cast-iron, five-plate stoves that were fed via an opening in the rear that was accessed from the back of the kitchen hearth (Fig. 4). Later, freestanding six- or ten-plate stoves came into use. Typical furnishings included a table and benches in the corner opposite the stove, along with a hanging cupboard or shelf. The door between the Stube and the adjacent Kammer (bedchamber) was often used to display a long, narrow piece of cloth known as a hand towel. Such towels were typically decorated with embroidery or drawnwork and have loops at the top corners so they could be hung from iron hooks or wooden pegs. Most were made by Mennonite and Schwenkfelder women in Lancaster, Lebanon, Berks, and Montgomery counties from about 1800 to 1880, although some Old Order Amish women continued making them into the early 1900s.

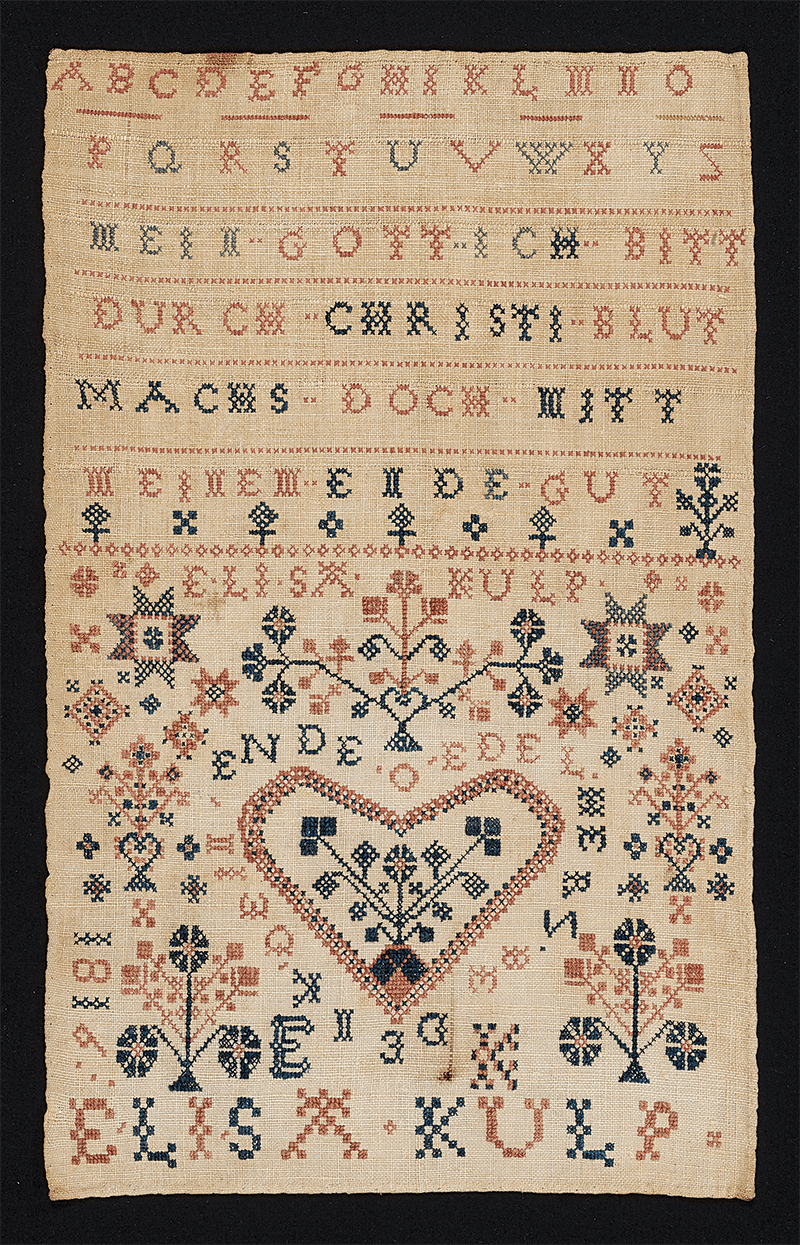

Needlework and quilting were used to ornament a variety of household textiles, including clothing and bedding. In Lancaster County, young Mennonite women made decorated aprons and handkerchiefs; the oldest known dated example was made for, and possibly by, Maria Huber at the time of her marriage in 1768. Samplers were also made by Pennsylvania German women of all religious backgrounds. The one stitched in 1816 by Elisa Kulp, a Mennonite, bears the inscription “O Edel Herz Bedenk Dein Ende” (O noble heart, bethink your end) around the heart at the bottom (Fig. 5). A common sentiment in Mennonite art reminding one to prepare for death, it usually appears as an acronym rather than spelled in full. Even the humble privy bag—used to collect scrap paper for the outhouse—was sometimes embellished with quilted or appliquéd decoration.

- Fig. 7: Baptismal wish for Stoffel Emrich, attributed to the Sussel-Washington Artist, Bethel Township, Berks County, Pa., ca. 1771. Watercolor and ink on laid paper, 7½ x 9¼ inches. Courtesy of Winterthur Museum, Garden & Library. Purchase with funds provided by Henry Francis du Pont (1958.120.15).

CHURCH

Bibles, hymnals, sacramental vessels, and other religious artifacts took on artistic dimensions in the hands of Pennsylvania German craftsmen. A diminutive walnut chest, made by an unknown German émigré cabinetmaker for St. Michael’s Lutheran Church in Philadelphia, features an image of the Agnus Dei or Lamb of God inlaid on the lid (Fig. 6). Its original function was likely to store communion wafers; the two slots in the lid were added later to convert it into a ballot or alms box.

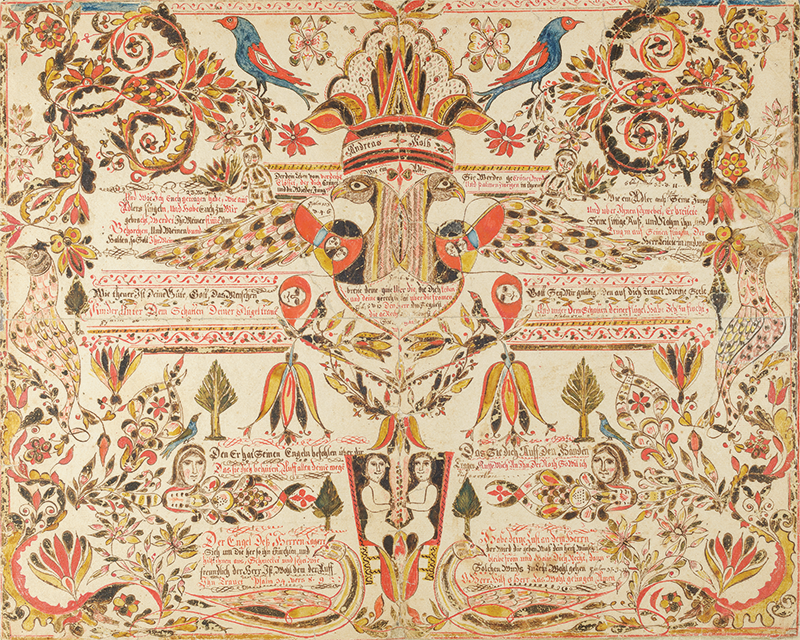

Because of the importance of infant baptism in the Lutheran and Reformed faiths, many Pennsylvania Germans commemorated the event with a decorated certificate. Handwritten or printed, these documents typically include genealogical data in addition to motifs such as hearts, flowers, angels, and birds. Some artists further embellished the certificates with human figures, such as the delightful rosy-cheeked people in colorful garb that adorn a baptismal wish made by the Sussel-Washington Artist (Fig. 7).

SCHOOL

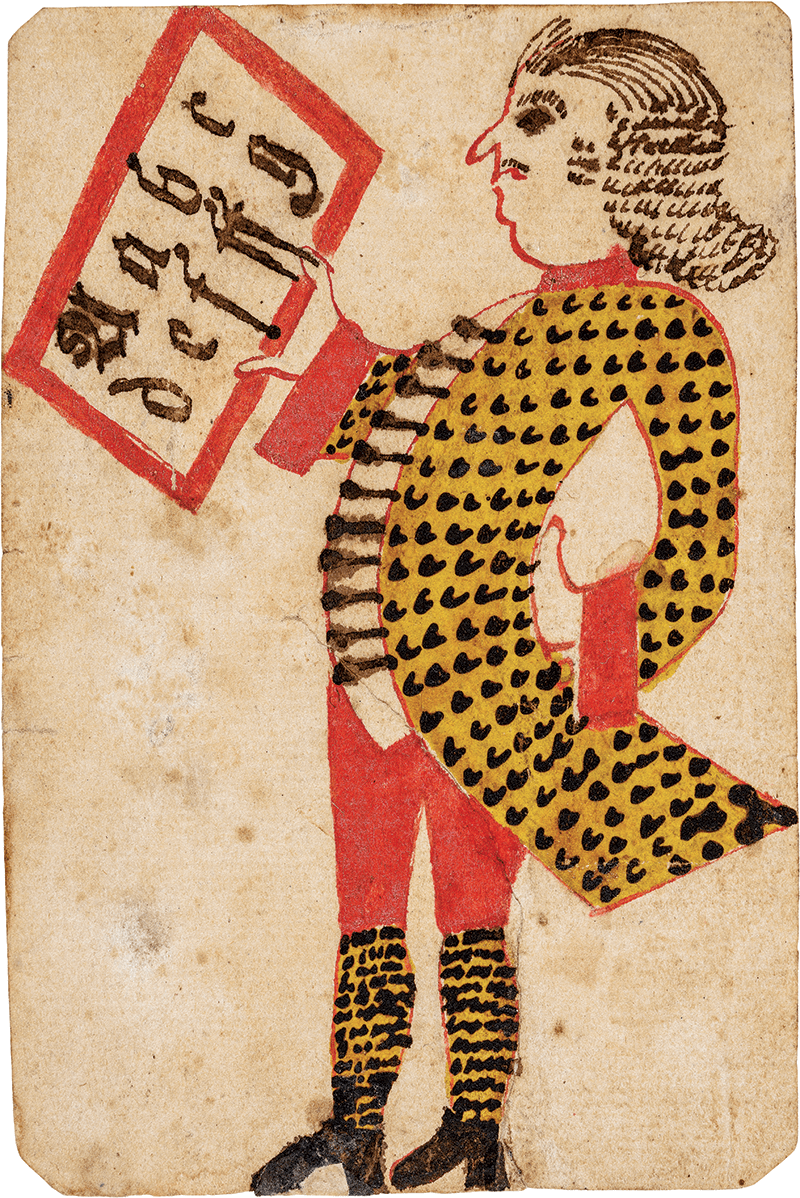

Prior to the passage of the Free Public School Act of 1834, most Pennsylvania German children were educated in church-affiliated schools. The curriculum included arithmetic, reading, writing, grammar, and religious or moral instruction. Classes were typically conducted in German, although by the early 1800s students were also taught to read and write in English. Fraktur documents were an important part of the educational system. Small drawings were presented to young children by their teachers as rewards of merit, such as the one of a bird given to Jacob Leith in 1818 when he learned his ABCs “with diligence” (Fig. 8). To help children learn to write, schoolmasters often gave them a Vorschrift, or writing sample. A typical Vorschrift begins with a biblical verse or hymn followed by the alphabet and numeral systems (Fig. 9).

Two of the most influential schoolmasters, Andreas Kolb and Johann Adam Eyer, were also prolific fraktur artists. Kolb and Eyer took inspiration from each other’s work, and taught countless pupils to write and draw in a similar manner (Fig. 10).

- Fig. 9: Writing sample for Jacob Beitler, attributed to Johann Adam Eyer (1755–1837), Deep Run area, Bedminster Township, Bucks County, Pa., 1782. Inscribed at the lower right (translation): “writing sample for Jacob Beitler, writer on the Deep Run” (a creek located in Bucks County, Pennsylvania). Watercolor and ink on laid paper, 8¼ x 13⅜ inches. Courtesy Winterthur Museum, Garden & Library. Purchase with funds provided by the Henry Francis du Pont Collectors Circle (2013.31.78).

- Fig. 10: Religious text, signed by Andreas Kolb (1749–1811), Montgomery County, Pa., ca. 1785. Watercolor and ink on laid paper, 13⅞ x 16½ inches. Courtesy of Winterthur Museum, Garden & Library. Purchase with funds provided by the Henry Francis du Pont Collectors Circle (2013.31.71). A stunning synthesis of design and text, this fraktur was acquired by Pastor Weiser from an Eyer descendant—suggesting that Kolb may have given it to Johann Adam Eyer as a special presentation piece.

- Fig. 11: Allegorical drawing of Simon Schneider/Snyder, attributed to the Engraver Artist, Southeastern Pa., ca. 1808. Watercolor and ink on laid paper, 3 x 5 inches. Courtesy of Winterthur Museum, Garden & Library. Purchase with funds provided by the Henry Francis du Pont Collectors Circle (2013.31.101).

NATION

By the late 1700s, many Pennsylvania Germans were engaged in state and national politics. The desire to protect their religious freedom and land grants—both factors in their decision to immigrate to Pennsylvania—was a driving force behind such activism. With increased civic engagement came an astonishing range of objects embellished with patriotic imagery, including spread-wing eagles bearing shields that were derived from the Great Seal of the United States. Contrary to “dumb Dutchmen” stereotypes, Pennsylvania Germans were politically astute. One artist celebrated the 1808 gubernatorial campaign of Simon Schneider/Snyder with a fraktur depicting Snyder as a large, spread-wing eagle surrounded by a flock of smaller birds (Fig. 11). The first of many Pennsylvania Germans to hold the governor’s office, Snyder led Pennsylvania during the War of 1812 and oversaw the relocation of the state capital from Lancaster to Harrisburg.

The extent to which the Pennsylvania Germans had embraced American culture by the 1800s is revealed by a pair of commemorative dishes, likely made after the fiftieth anniversary of the Declaration of Independence and the centennial of Independence Hall’s construction (Figs. 12a, b). A blend of traditional folk art and patriotic symbolism, these objects reveal how the Pennsylvania Germans actively participated in the formation of a national identity in which all could share, regardless of their ethnic background.

- Fig. 12a, b: Pair of dishes, attributed to Absalom Bixler (1802–1884) or his brother Jacob, Lancaster County, Pa., ca. 1830. Lead-glazed earthenware, H. 1½, Diam. 14⅛ inches. Courtesy of Winterthur Museum, Garden & Library. Bequest of Henry Francis du Pont (1967.1660 and 1967.1662).

The Independence Hall dish honors its master builder, Edmund Wooley; the dates 1732 and 1741 on the rim refer to the beginning and completion of construction. The other dish features the Liberty Bell with the inscription “DER FRIHIDE GLUG 1776 WASHINGTON” (The Liberty Bell 1776 Washington).

A Colorful Folk: Pennsylvania Germans & the Art of Everyday Life, at Winterthur Museum, Garden and Library, Delaware, is open through January 3, 2016, with a full-color catalogue funded by the American Folk Art Society and the Shelley Pennsylvania German Heritage Fund. Two related exhibitions are: Drawn with Spirit: Pennsylvania German Fraktur from the Joan and Victor Johnson Collection, at the Philadelphia Museum of Art through April 26, 2015; and Quill & Brush: Pennsylvania German Fraktur and Material Culture, at the Free Library of Philadelphia through July 17, 2015.

Lisa Minardi is an assistant curator at Winterthur Museum and a specialist in Pennsylvania German art and culture.

This article was originally published in the Summer 2015 issue of Antiques & Fine Art magazine, a digitized version of which is available on afamag.com. Antiques & Fine Art, AFAmag, AFAnews, and AFA Publishing are affiliated with InCollect.com.