A Folk Art Life with Allan & Penny Katz

|

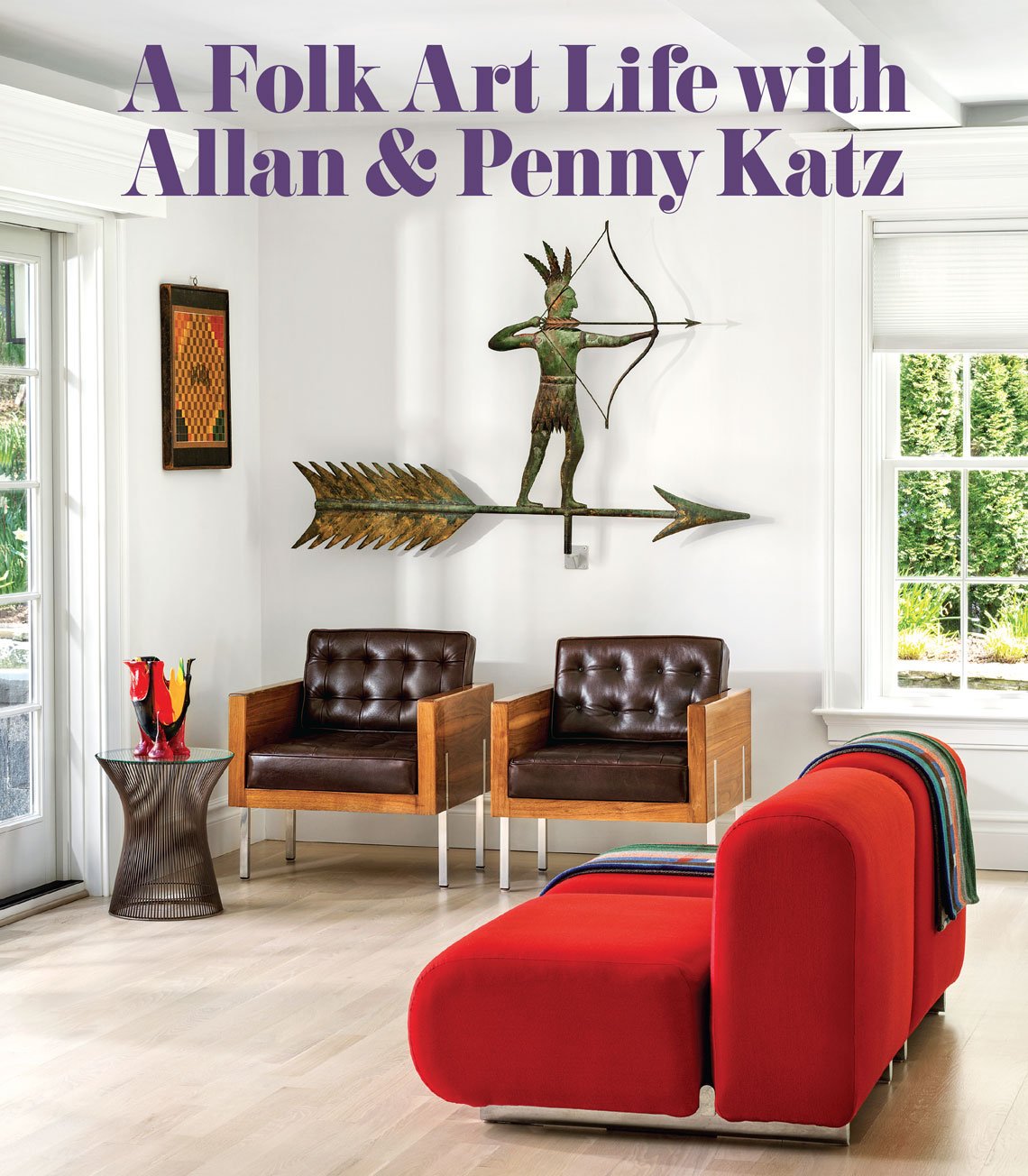

Rare Folk Art pieces from the Katz’s collection create a timeless mix combined with the bold forms of modern furniture. The chairs are vintage mid-century Florence Knoll prototypes that were never produced, and the sofa is by Kazuhide Takahama for Knoll. Warren Platner’s iconic and sculptural side table is topped with a vase by Gaetano Pesce. On the wall at left, the playful side of Folk Art (literally) is illustrated with a polychrome decorated gameboard for the Victorian-era game of Halma. The game itself is lost to the ages, but the gameboard has a decidedly Modernist sensibility. An Indian archer weathervane presides over the seating area, a powerful symbol of Americana and an example of glorious artisanal craftsmanship. |

Text: Benjamin Genocchio

Photography: Ellen McDermott

Interior Design: Melissa Barak Weiss, Indigo Interiors Co

Architecture: CK Architects, Guilford, CT

Garden Design: MJ McCabe Garden Design

|

llan and Penny Katz have been on a journey. The 76-year-old Allan beams with energy and enthusiasm as he stands in his gallery, on the property of an immaculately renovated 1830s historic house on one of the more prestigious streets in the shoreline town of Madison, Connecticut. He’s describing the moment when 51 years ago, he discovered and bought his first weathervane. “I remember that day,“ he says, “the object just totally resonated with me.”

It was 1971, and Katz had graduated college with a degree in economics, completed his active duty as an Army reservist, and had started an electronics company with his college roommate. Although consumed by his new company, he somehow found time to make the rounds of antique shops that once were abundant in New England towns.

Katz had always been a collector. He collected stamps and coins as a kid and even built a miniature natural history museum in the basement of his home in Queens, New York. He formed his first real collection in the early 1970s, he says, focusing on American stone lithography advertising signs on tin from the 1870s–1890s, continuing to acquire them throughout the next decade. He sold his business in the early 1980s, and by 1983 had developed a growing reputation as a passionate collector of the increasingly popular genre of American Folk Art.

|  | |

Allan and Penny Katz at home. Their house is a historic structure and bears a plaque listing it as “The Jonathan Dudley House c. 1830.” | ||

The bulk of the material that Katz related to falls into the category of Folk Art that began with objects designed to be used as advertising for merchants, but with a distinguishing creative component or original craftsmanship that takes it beyond the utilitarian. “The category is inclusive, not exclusive,” Katz says, “indeed this is what the category is all about, embracing individual pieces by unknown makers and bodies of signed works.” This is the art of the emerging middle class in America and has a lot to say about the people who came here and how this country was formed.

| |

Hanging on the wall, a stunning and important work, “Exciting Event” by Bill Traylor, a Black Folk Artist born enslaved, whose work depicts simple, traditional folkways, often with veiled and potent symbolism or allegorical meaning. A design dating to 1929, the Mies van der Rohe Barcelona coffee table displays a carved pipe display piece circa 1880 by William DeMuth, from his tobacco shop on Broadway, NYC. |

“I always like to say that I didn’t pick Folk Art but rather that it picked me,” he says by way of an explanation as to how he came to specialize. “I didn’t come from a wealthy family so my entry point was at a price that was reasonable, the material was available and interesting.” The field was wide open back then, he recalls. “Folk Art is at the root of every culture in the world. It had taken time for a young America to begin to celebrate its own Folk Artists. They were greatly influenced by America’s melting pot culture. To an extent, as a market genre, it was somewhat young in the formation stage when I began collecting.”

Collecting led Katz into dealing, he says. He was invited in 1983 to take a booth at the Fall Folk Art Show in New York, organized by show promoter Sandy Smith, who was a friend and knew of his collecting interests. “Sandy would save a booth each year and invite a collector who wanted to show and maybe sell some of their excess pieces, and I got the booth that year. That was my first show.” He became a full-time dealer around 1985, selling out of his home, and became a regular on the antique show circuit.

For the next decade, Katz did 12–14 shows a year all over the country, focused on Folk Art. It was, he says, a tremendous education. “During the 1970s and 80s, so much new material was being discovered that it allowed someone to get a lot of on-the-job education and training, especially as prices were more relaxed. You could learn a lot by buying it, living with it, learning about it, and taking it to shows to see how it resonated with others. There were also books being published and museum shows. I was honored to be part of a generation of dealers and collectors that were permitted to judge the material as it was increasingly being discovered.”

|

The elegant and romantic nineteenth-century swan child’s sled is one of the cornerstone pieces of the Katz’s collection, They have lived with and loved it for over 35 years and as Penny Katz remarked, “It’s everyone’s favorite.” |

|

The living room’s suite of lounge chairs by Swiss mid-century designer Robert Haussmann are generously scaled but low in profile, to ensure uninterrupted sight lines to the richly patinated Folk Art treasures. Above the fireplace, a circa 1880 needlework panel from Pennsylvania shares the room with a carved and paint-decorated “Cubist” blanket chest by Alexander Couard. |

As the Folk Art market matured, so did Katz as a collector and dealer. He began to focus more on finding higher-end pieces, and doing shows with better works. He also sold out of his house in Woodbridge, Connecticut from 1996, when he and Penny were married, until 2018 when they purchased and renovated the property in Madison, where they built the dedicated sales gallery. In their new home, they collaborated with their design team, mixing together the best of their Folk Art collection assembled over many decades, with modern and contemporary furniture by Florence Knoll, George and Mira Nakashima, Robert Hausmann and Mies van der Rohe along with artworks by artists including Bill Traylor, Anni Albers, Jacob Lawrence and the Japanese abstract expressionist Kenzo Okado.

| |

“In 1995 we purchased a set of six Conoid chairs circa 1970 by George Nakashima from a New York City gallery. We were attracted by their beauty, comfort and the simplicity of their design. We then had the wonderful experience of meeting Mira Nakashima at her studio in New Hope, Pennsylvania where Penny and Mira together assessed the slabs in George Nakashima’s still-extant wood pile to choose the piece for her to make an accompanying table for her father’s chairs.” On the wall is an American painted sheet and wrought iron weathervane, circa 1910. |

Today, Katz is well known to viewers of the PBS television series Antiques Roadshow, where for 18 years he has been a hugely popular consulting specialist for Folk Art, radiating personal magnetism and dispensing profound commentary in nearly equal measure. His love and respect for the art form is infectious and completely genuine. When I visited, he and his wife and business partner Penny had just returned from taping a new show at the Filoli Gardens in Woodside, outside of San Francisco. The following week they were headed to Shelburne, Vermont for another taping. “You never know what is going to show up on the Folk Art table, which is the joy of doing this — it’s always a surprise.”

Katz specializes in 3-dimensional objects, sculpture mostly, a subject on which he is widely considered to be an expert. He’s currently putting finishing touches on orchestrating (for a client) the donation of a multi-million dollar weathervane to a prominent New York City museum where it will be viewed by millions of people each year. “I’ve handled 2-dimensional objects like great samplers and portraits but I never wanted to build my brand around that. I am drawn to the sculptural field.”

It would be difficult today to assemble the kind of collection that Allan and Penny have in their home in Connecticut. “This is a lifetime of sorting and winnowing,” he says, ushering me into his living room to review some of his favorite objects. He pointed to a metal gilded eagle on the wall. “That came from the United States embassy in Canton in southern China. It is a replica of the Great Seal of the United States, by an unknown maker circa 1870–1880.” He then showed me an American Indian archer weathervane which is well known, as it was in the collection of Stuart Gregory, one of the great early pioneer Folk Art collectors. Dating to circa 1870, it is made of copper with traces of gold leaf and originally sat above a blacksmith’s shop in Pomfret, Connecticut.

|

The 1830s fireplace is original to the house. Dating 100 years later circa 1930, a pair of Art Deco chairs are from the lounge at The Strand Theatre in Boston, Massachusetts. |

|

Left: Antique Japanese “Boro” circa 1890. Right: Male and female wooden mannequins with articulated limbs, New York State, circa 1915. |

“The wonderful thing about this democratic art of Folk Art is that it was for everybody. This was public art, Penny says. Allan quickly also adds, “Remember it very often had a utilitarian function,” and points to a signed, dated life-size tobacco store trade figure made by Herman Kruschke in Rochester, Minnesota in 1880 that depicts an Indian chief with all original paint and in remarkably good condition. “If you take yourself back to 1880, you can see a beautifully carved figure standing outside a trading store or some other commercial enterprise with the message of what is sold inside. It catered to a vast immigrant population who in most cases either did not speak English or might have been illiterate. It was a means of communication.”

Another fascinating object is a banjo chair from New Hampshire circa 1920, made of a variety of woods. The chair has the shape and decoration of a life-size banjo complete with inlaid strings. It has a practical role as furniture but its visual decoration suggests it was something more special, a talking point or showpiece, and is accompanied by a tambourine-shaped footstool. There are five known chairs and two known footstools, Katz tells me. “Creative, beautifully crafted yet whimsical, it is what the folk spirit is all about. You identify it as a chair yet it is something else.”

|

Penny’s collection of German and Czech Art Deco airbrush glaze ceramics. The 100-piece collection began with a blue and white pot that Penny admired, and Allan bought as a gift for her when the couple was dating. It remains a sentimental favorite. |

|

An apiary (beehive) in the form of a Civil War soldier, 1900, DeKalb County, Georgia is one of Allan’s “all-time favorite pieces.” Workshop, Jacob Lawrence, 23/100, signed and dated 1972. Lawrence was a social realist whose work depicted the lives and struggles of African Americans. He grew up in Harlem during the Depression, going on the become successful and one of the first nationally recognized Black artists. |

Nearby is an elegantly carved swan sled, created in the nineteenth century by an unidentified maker, something Penny says has been an important and nostalgic part of their home environment for over thirty-five years. “It speaks of a more romantic time in our country’s history. Perhaps it was lovingly created by the maker for his own children. It was not commercially produced. We know of only one other (much smaller) swan sled created by the same hand. It’s everyone’s favorite.”

Much time and care has gone into the interior design of the home which presents a new model of the way in which folk art may be integrated into contemporary interiors. “So much of the roots of Folk Art were mired in the antique world. We’re trying to show how the material can live with other categories of art in our expanded collection.” To that end, they hired CK Architects from Guilford, Conn. to redesign both floors of the house, which they gutted, and interior designer Melissa Barak Weiss from Indigo Interiors Co. to help with the layout for the rooms and collection display. They engaged lighting consultant Monica Cotton to make sure everything was lit to its utmost advantage.

|

An interior view of the gallery, which is open by appointment. A few highlights from the offerings: (left to right): on the back wall, a painting by Purvis Young, a ceramic portrait bust of an African American, an oversized rooster weathervane, a large soldier whirligig, a Vermont paint-decorated blanket chest, and a Cotswald ram weathervane. |

|  | |

Outdoor views of the gardens and entrance to the Gallery (below). The figure in the garden is a double-sided cast iron sculptural advertising sign from the 1920s, touting the benefits of the patent medicine Vega-Cal. | ||

|

|

The lion sculpture, dated 1845, is one of the earliest surviving American trade signs. Originally atop a hardware store in Virginia, the lion’s front paw rests on an anvil to indicate that they made some of the tools sold in the store. |

If there is a word that describes the interiors it is restraint — fewer, better pieces of art and design are installed sparingly throughout the open-plan rooms, which flow easily into one another and allow visitors to take in artworks and furniture of different genres and time periods together. It also enables wonderful moments of surprise such as the rainbow-hued wall of airbrush glazed German and Czech Art Deco pottery from the 1920s and early 30s, collected by Penny starting in the early 1990s.

“When I met Allan he was already a dealer participating at shows around the country. He said to me — ‘look, if we are going to be dating it would be great if you would collect something,’ ” Penny says. That was in 1992 and Penny, who has a master’s in social work from Columbia University, was working at a hospital in New Jersey. “We were exhibiting at a show when I spotted an interesting blue and white Art Deco ceramic. I really loved it so Al bought it for me as a present. Then we went on this life journey together.” They were married in 1996, and 26 years later that initial gift is now the centerpiece of a 100-piece collection of Art Deco ceramics, displayed in custom-built shelving.

|

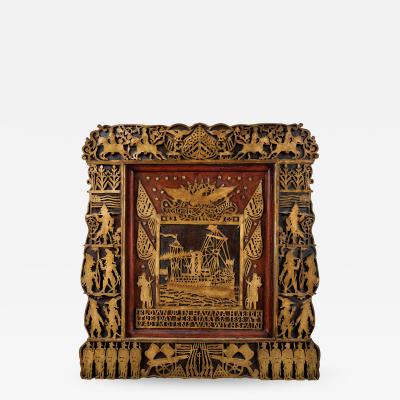

Mounted high above the portal, a carved and paint decorated eagle plaque, maker unknown, Maine, circa 1918. A trio of circa 1890s Southwest Native American “Ollas” (cooking or storage pots) from the Zia and Acoma Pueblos in New Mexico line the top shelf above a row of closets. At the end of the hall hangs a contemporary Tramp Art-inspired frame by Freeland Tanner of Napa, California. A midcentury classic, Eero Saarinen’s Tulip Table is paired with equally iconic chairs by Jens Risom. Because of World War II material shortages, the chairs were originally produced with rejected parachute straps. Centered on the table, a contemporary red pottery Face Jug vessel by A.V. Smith, Sanford, North Carolina. |

|  | |

| Left: Female bottle cap figure by Clarence and Grace Woolsey, Lincoln,Iowa, circa 1975. Right: Allan and Penny are also connoisseurs of fine design in many additional genres. The couple commissioned artisan John Russell of Guilford, Connecticut to design and craft their custom bamboo bed, which is built into the wall. Above the bed, a circa 1970 work in oil and rice paper on canvas by Kenzo Okoda, a Japanese American Abstract Expressionist. | ||

Their adjacent gallery (by appointment) is filled with wonderful diverse works including a large, patinated weathervane of a fleecy Cotswold ram that once, given its scale, likely sat atop a woolen mill. “It was never meant to be put in front of you at eye level and called a piece of American sculpture,” Katz says, “and yet the makers felt the need to be creative, to have these realistic details, to make it a more beautiful object.” That’s what I admire in Folk Art, this rebellious attitude that gave its makers the freedom to put their own twist on something. It is what I am always connected to.”

Collecting Folk Art has been a very personal journey for Allan and Penny and one, Penny says, that changed over time. “We have chosen to surround ourselves with art, color, light and with objects that energize us and enrich our life. They give us a sense of history, place, and purpose and are timeless. We each have our favorites but are respectful of our differences in style, taste, and the choices we have made. We hope this journey will continue to expand, evolve and change for a long time to come.”