A Hancock Family Story: Restoring Connections

“Discovery is not about seeing something

but about making a connection.” 1

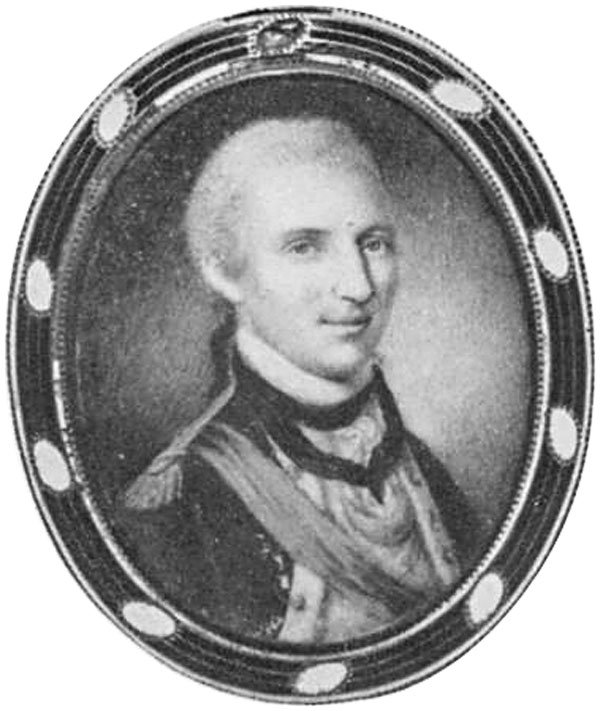

Research can lead to unexpected surprises. Such was the case as I conducted a study of the portrait subjects painted by artist John Smibert (1688–1751). An anomaly in a published resource regarding the sitter Lydia Henchman Hancock opened an avenue of discovery relating to the family of patriot John Hancock and three portrait miniatures: of Hancock and his two children, Lydia and John (Figs. 1-3). Hancock family descendants owned the miniatures until 1932 when they entered a museum collection. They have been resting in storage for eighty-five years, disconnected from their context and proper provenance. What follows is a story of discovery and of setting the record straight.

| |

| Fig. 1: Charles Willson Peale (1741-1827), Portrait of John Hancock, 1776. Watercolor, 1½ x 13⁄16 inches. Mary B. Jackson Fund (32.021.1). Museum of Art, Rhode Island School of Design, Providence, R.I. |

When they were married, merchant Thomas Hancock (1703–1764) commissioned John Smibert to paint portraits of himself and his new bride, Lydia Henchman Hancock (1714–1776), and their parents.2 One of the wealthiest men in America, having founded an extensive mercantile empire, the House of Hancock, Thomas Hancock built a mansion in Boston on Beacon Hill, and, unusual in colonial America, filled it with paintings: Dutch masters, landscapes, and portraits of family, friends and business partners.

In addition to the Smibert portraits, Thomas Hancock commissioned portraits of Lydia and himself by other artists, including miniatures by John Singleton Copley (1738–1815) (Figs. 4, 5). Having no children, they adopted Thomas’s nephew John after his father, the Reverend John Hancock, died in 1744. When Thomas died, twenty-seven-year-old John inherited the international business empire and continued adding to the art collection.

While researching portraits of Lydia, I discovered a listing in the Smithsonian Art Inventories Catalog for an “unlocated” portrait miniature in oil [sic] of “Hancock, Thomas, Mrs. (Lydia Henchman)–Child” painted by Charles Willson Peale (1741–1827) in 1777. It was further identified as No. 354 in Charles Coleman Sellers’ Portraits and Miniatures by Charles Willson Peale (hereafter P&M ).3 However, the death date was incorrect—Lydia Henchman Hancock died April 25, 1776. Furthermore, Peale could not have painted her as a child since she was twenty-seven years old when he was born. Concurrently, the National Portrait Gallery’s Catalog of American Portraits (CAP) recorded a miniature, watercolor on ivory, of “Lydia Henchman Hancock, (1714–1777),” painted by Peale between 1777–1780, in the collection of the Museum of Art, Rhode Island School of Design (RISD). No P&M number was given; the portrait was placed in the category: “Society and Social Change\Wife.”

As it happens, there were two Lydia Henchman Hancocks. John Hancock’s daughter Lydia, named after his aunt Lydia, was born in November 1776 and died at age nine months in August 1777. The two Lydias were conflated in the records: the 1777 death date was correct for the younger Lydia, while the 1714 birth year was correct for the elder Lydia. The Sellers P&M listing No. 354 was for an unlocated miniature of the infant Lydia, probably painted posthumously. Was the miniature at the RISD Museum an unknown portrait of Aunt Lydia—or was it perhaps the unlocated Peale portrait of baby Lydia?

The Catalog of American Portraits also records two other Hancock family miniatures in the RISD Museum collection—a miniature of John Hancock by Peale (no P&M listing given) and a portrait of his son, John George Washington Hancock (1778–1787), by an unknown artist. Simultaneously, the Art Inventories Catalog has records for “unlocated” portrait miniatures by Peale of John Hancock (P&M No. 351) and “Mrs. John Hancock,” (P&M No. 353), painted in 1775. Her name, Dorothy Quincy Hancock, is not given in the CAP record.

According to Maureen O’Brien, curator of painting and sculpture at RISD, there are three miniatures in the RISD collection—a portrait of John Hancock attributed to Peale and set as a brooch, and portraits of his children, Lydia Henchman Hancock and John George Washington Hancock (“Johnny”), placed in a double-sided locket. They were acquired through a dealer who claimed they had descended through the Hancock family.

|  | |

| Fig. 2: Charles Willson Peale (1741-1827), Portrait of Lydia Henchman Hancock, 1777. Watercolor, 1⅝ x 1⅛ inches. Mary B. Jackson Fund (32.021.2). Museum of Art, Rhode Island School of Design, Providence, R.I. | Fig. 3: Portrait of John George Washington Hancock, 1785-1787. Watercolor, 1 5⁄16 x 1⅛ inches. Mary B. Jackson Fund (32.021.3). Museum of Art, Rhode Island School of Design, Providence, R.I. &frac516; |

Research was undertaken in an effort to confirm or dispute the claim. A series of letters in the RISD archives revealed that in January 1932, a woman attempted to sell three miniatures to the Boston jeweler Frederick T. Widmer, saying they had always been in her family.4 Widmer offered them to William Cushing Loring, a RISD department head, a member of the Museum Committee, and an art dealer. The John Hancock miniature by “Charles Wilson [sic] Peale” was priced at $1,200, and a miniature locket containing portraits of the children of John Hancock, “artist unknown,” was priced at $300. After researching the children’s portraits, Loring wrote to the museum director: “The miniature of the little girl has been attributed as without doubt, to Charles Wilson [sic] Peale.” 5 The museum purchased the miniatures. However, Widmer neglected to tell Loring who had sold him the miniatures and Loring did not tell Widmer that the baby’s portrait was probably also by Peale. The miniatures were placed in storage and the chain of provenance was broken.

Serendipitously, I found the key to the miniatures’ story in the collection of the Massachusetts Historical Society.6 Thomas H. Wood, a Hancock family descendent, had donated black and white photographs of Lydia and Johnny’s miniatures in 2012. It was frequently the custom to make such photographs of family paintings for relatives who did not inherit the originals. The photographs were accompanied by the following “granny note”: “Photograph of Miniature on one side of large Gold locket. John George Washington Hancock. Only Son of Gov. John and Dorothy Hancock. Died from fall on the Ice. Locket is Gold with dark blue enameled frame & gold (stars or dots) between 2 & 3 in. long. Min. of Sister Lydia on the other side. Photograph of miniature on one side of large Gold locket. Only Daughter of Gov. John and Dorothy Hancock. Lydia Henchman Hancock. Gold Locket was enameled with dark blue with gold spots or stars. It was the only picture of Lydia and very much prized by E.L.H. Wood. It was sold to Frederick J. Widmer. 31 West St., Boston. By her daughter Mary Wood Cole for $50.00. I went to Widmer’s, but he said he knew nothing about having bought the Locket. Morton Cole said he would try to Trade it for us, but he never did it.”7

Thomas H. Wood told me (personal email 11/24/15) that the author of this note was his grandmother, Emily Niles Lockwood Wood. She was Mary Wood Cole’s sister-in-law. E.L.H. Wood is identified as Elizabeth Lowell Hancock (Moriarty) Wood, great-granddaughter of Ebenezer Hancock (1741–1819), John Hancock’s brother. Mary Wood Cole was her daughter. Morton Cole was Mary’s son. The miniatures were passed down through the family until sold to Widmer in 1932.

The note did not mention the John Hancock miniature, even though it had been on Widmer’s invoice. Fortunately, as evidence that it had descended in the Hancock family, there is “a photograph of John Hancock” in the MHS collection, also donated by Thomas Wood. The item, a daguerreotype in a leather case and described as a painting of John Hancock, turned out to be the reverse image of the miniature at the RISD Museum.8

Further validation of the provenance of the three miniatures was found in the will of John Hancock’s nephew, dated April 1, 1857. Also named John Hancock, he was married to Dorothy Hancock Scott’s stepdaughter. (Dorothy married Capt. James Scott after John died in 1793.) He bequeathed “a miniature of Gov. Hancock” to his son Washington and “the miniatures of my cousins John George Washington Hancock and Lydia Hancock” to his son Franklin. Subsequently, the miniatures appear in an inventory written in 1917 by his granddaughter, Elizabeth Lowell Hancock (Moriarty) Wood in which she noted who was to inherit various items. She designated a “Gold locket, with miniatures of Gov. Hancock’s two children” and a “Broach [sic],” with a portrait of Gov. John Hancock, as being reserved “for Mary.” This was Mary Wood Cole, her daughter. The black and white photos were also listed in the inventory.9

|  | |

| Fig. 4: John Singleton Copley (1738–1815), Lydia Henchman Hancock, 1766. Oil on copper, sight, 3⅞ x 2⅞ inches. National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution; Gift of Charles H. Wood and museum purchase. Conserved with funds from the Smithsonian Women’s Committee. | Fig. 5: John Singleton Copley (1738–1815), Thomas Hancock, ca. 1758; enlarged 1766. Oil on copper, sight, 3⅞ x 2⅞ in. National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution; Gift of Charles H. Wood and museum purchase. Conserved with funds from the Smithsonian Women’s Committee. |

While the Peale miniature of Dorothy Hancock is still unlocated, and there is no known image of it, John Singleton Copley painted a portrait of her about 1772. Only four years earlier than Peale’s miniatures of Dorothy and her husband, it seems plausible that her likeness in the missing miniature was very similar to the young woman seated at the table in Copley’s portrait (Fig. 6).10 There is, however, one miniature of Dorothy by an unknown artist that is recorded in a photograph. It is not contemporary with her husband’s miniature, but instead depicts Dorothy in her advanced age (Fig. 7); the location is presently unknown.

Fortuitously, further research discovered a lithograph of this portrait in the MHS collection. The inscription in the plate, “Mrs D. Scott Miss Goodrich pinx.,” allows us to identify the artist as either Sarah Goodrich/Goodridge (1788–1853), the well-known Boston miniaturist, or her sister Eliza Goodrich/Goodridge (1798–1882). The lithograph was drawn by Thomas Edwards (1795–1869) and was published by the Senefelder Lithographic Company of Boston.

Now that the identity of the sitters in the miniatures have been clarified, let’s look into their history. After John Hancock and Dorothy Quincy were married in August 1775 the couple set up house in Philadelphia, where John served as president of the Second Continental Congress. Charles Willson Peale also came to Philadelphia, to open a studio as a portrait painter.11 Peale recorded in his diary that in January 1776, John Hancock, one of his first customers, commissioned miniatures of himself (fig. 1) and Dorothy.12 On July 4, 1776, Founding Father John Hancock signed the Declaration of Independence. In November he became a father when Lydia Henchman Hancock was born, named for John’s beloved Aunt Lydia who had died in April.13 On December 3, Peale recorded John Hancock’s final payment of twelve guineas for the miniatures in his diary, just before he left to join Washington’s Army (Fig. 8).

Fearing an imminent British attack on Philadelphia, Congress removed to Baltimore, Maryland, in December. Dorothy and Lydia went with John. The British Army passed by Philadelphia, so in March 1777, Congress made plans to return. John traveled back to the city alone, Dorothy and Lydia to follow later. He wrote to Dorothy on March 10, “I have sent everywhere to get a gold or silver rattle for the child with a coral to send but cannot get one. I will have one if possible on yr. coming. I have sent a sash for her...” The purple sash Lydia wears in the miniature is likely this present from her father.14

Dorothy returned to Philadelphia with a very sick baby. There were bills for a doctor’s care and medicine even before they left Baltimore. Baby Lydia died in August 1777. John Hancock called upon carpenter David Evans, the man who had made his “Desk for congress,” “for a Mohagany [sic] Coffin 2 feet 6 inches long.” 15 This bill, dated August 11, is the only record of Lydia’s death.

|  | |

| Fig. 6: John Singleton Copley (1738–1815), Dorothy Quincy (Mrs. John Hancock), about 1772. Oil on canvas, 50⅛ x 39⅝ inches. Museum of Fine Arts, Boston (1975.13); Charles H. Bayley Picture and Painting Fund and Gift of Mrs. Anne B. Loring. | Fig. 7: Mrs. John Hancock (Dorothy Qunicy) [sic]. Artist unknown, American School, Massachusetts, 1801–1850. Miniature on ivory, 3⅞ x 3 inches. Image courtesy of Frick Art Reference Library Photoarchive. Photographer Ira W. Martin. The current location of this work is unknown. |

Having just returned to Philadelphia, Peale must have painted the posthumous miniature of Lydia at this time; he did not keep his diary from July through September 17. Nonetheless, Charles Coleman Sellers wrote: “On several occasions in his career Charles Willson Peale was asked to undertake the disagreeable task of painting a dying or dead child, including children of John Hancock, William Delany, and Richard Tilghman. In no case has such a portrait survived.” 16 Lydia’s portrait (fig. 2) is set against a background of evening clouds and a distant landscape holding a fully open white rose, a symbol of youthful feminine purity and innocence. The urn and weeping willow in her portrait are standard mourning iconography.17 Peale was known to base portraits of absent children on their parents’ features. Lydia’s portrait echoes John’s. Peale wrote to Hancock on July 24, 1780, requesting payment for the miniature. Again, on June 20, 1784, Peale reminded him: “I do not recollect to have received any pay for the portrait which I made in miniature of the little one which you lost when in this city.” 18

By the end of August, Philadelphia was bracing yet again for a possible British incursion. John sent Dorothy home to Boston, while he fled with the Congress to York, Pennsylvania. On September 26, 1777 the British conquered Philadelphia. In October the fortunes of war began to improve for America with the great victory at Saratoga and when the French became allies. But John Hancock was worn out and sick. He had lost his child and was worried about his wife. He resigned on October 29 and returned to Boston having served longer than any other President of Congress had or would during some of the most difficult times.

| |

| Fig. 8: Charles Willson Peale (1741–1827), Self-Portrait as a Revolutionary War Captain in the Philadelphia Brigade, 1777–1778. Oil on canvas, 13 x 12½ inches. Courtesy, American Philosophical Society. This image was recently in the exhibition at the American Philosophical Society Museum in Philadelphian (April 7-December 30, 2017), Curious Revolutionaries: The Peales of Philadelphia, about the Peale family’s role in shaping early American public culture through innovations in art, science, and technology. |

John George Washington Hancock (“Johnny”) was born in May 1778. In June, Hancock briefly returned to Congress after the British abandoned Philadelphia, but soon went home to Boston. He was overwhelmingly elected the first American governor of the State of Massachusetts in 1780 and went on to serve nine terms. Tragically, on January 27, 1787, Johnny died when he hit his head in an ice-skating accident. Johnny’s portrait (fig. 3) was either painted during one of the last years of his life or posthumously, so a probable date for the portrait is between 1785 and 1787.19

The portraits of the children were probably placed in the exquisite sapphire-blue enamel and gold, double-sided locket to be worn as a piece of mourning jewelry. There is one similar locket known, which contains a miniature (also by Peale) of a young General Hans Christian Febiger (1746–1796) on one side (Fig. 9). At his death, his wife reset the miniature as a mourning pendant, with the reverse containing a black and sepia painting on ivory of a weeping woman leaning over a tomb, with an inscription mourning his death at age fifty.20

Considered together, the Hancock family miniatures are illustrative of the evolution and use of the portrait miniature in America: the earliest, of Thomas and Lydia by Copley, were oil on copper, patterned after early English models; those of John and Dorothy by Peale were mementos to commemorate a marriage, designed to be worn as intimate jewelry; that of baby Lydia, and probably the one of Johnny, served as memorials; and the Goodridge miniature of Dorothy as an old woman was painted in a larger, rectangular format meant to be framed and displayed, or to be carried in a case. Lithography (invented in 1796) was used to reproduce and make multiples of artworks for sale or publication. Daguerreotypes, and then photography, came to largely supplant the painted miniature.

|  | |

| Fig. 9: Front and rear views of the locket containing the miniature of Colonel Christian Febiger by Charles Willson Peale. The miniature was painted ca. 1781 while the mourning picture on the reverse was painted ca. 1796. The current location is unknown. See Charles Coleman Sellers, Charles Willson Peale with Patron and Populace, vol. 59 (American Philosophical Society, 1969), 138. | ||

As Robin Jaffe Frank so beautifully put it in her book on miniatures, “Regardless of whether the sitters’ accomplishments remain memorable to us today, the existence of their likenesses in miniature means that somebody cared deeply about them.” 21

Pamela Ehrlich is an independent researcher, archaeologist, and artist. She thanks the efforts of all the people who collect, preserve and protect the records and material culture of America, and is especially grateful to Ms. Maureen O’Brien and Ms. Anne E. Bentley, and to Mr. Thomas Wood and Mr. John Anderson who generously shared their family history.

This article was originally published in the 18th Anniversary issue of Antiques & Fine Art magazine, a fully digitized version of which is available at www.afamag.com. AFA is affiliated with Incollect.

2. Smibert’s painting of Thomas Hancock is in the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston and Lydia’s is in the Colby College Museum of Art. The portraits of Thomas’s parents, the Rev. John Hancock (1671–1752) and Elizabeth [Clark] Hancock (1687–1760), are in the Hancock-Clarke House in Lexington, Mass.; Lydia’s parents, Daniel Henchman and Elizabeth Gerrish/Jerrick Henchman, are at the Cincinnati Historical Society, Cincinnati, Ohio.

3. Charles Coleman Sellers, “Portraits and Miniatures by Charles Willson Peale,” Transactions of the American Philosophical Society, new serial, vol. 42, pt. 1 (Philadelphia: American Philosophical Society, 1952), No. 354, p. 98.

4. A series of letters in the then-director’s correspondence detailed how the portraits entered the collection. My appreciation goes to RISD curator Maureen O’Brien and archivist Douglas Doe for their generous help.

5. Letter to Mr. L. Earle Rowe from William C. Loring, February 12, 1932. He showed Lydia’s portrait to Mr. Harry B. Wehle of The Metropolitan Museum of Fine Art, who said: “it might well be a Peale.” Wehle was the author of American Miniatures, 1730–1850. Loring also consulted the noted miniature collector, Mrs. Dorothy Gannett (interior designer Dorothy Draper), who “felt from the first instant that it was a Charles Wilson Peale.”

6. I first saw the black and white photographs published in the on-line article “Mourning the Hancock Children, Lydia & Johnny,” October 23, 2014, http://www.silkdamask.org/2014/10/mourning-jewelry-portrait-miniatures.html. They are also pictured on https://www.findagrave.com and on www.geni.com. They were first published in 1905 in Dorothy Quincy, Wife of John Hancock and Events of her Time by Dorothy’s great-great niece Ellen C.D.Q. Woodbury.

7. Personal email from Ms. Anne E. Bentley, curator at the Massachusetts Historical Society, Nov. 9, 2015.

8. My thanks to Sabina Beauchard of the MHS for taking a photograph for my research. The daguerreotype (visible oval image 1¹⁄₃ x 1 in. [ninth plate]; case: 3 x 2½ in.) was probably made by Southworth & Hawes, in business in Boston 1843 to 1863. The pictures of the miniatures of the children are later photographs on paper with 20th-century frames.

9. My thanks to Hancock family descendant Mr. John Anderson for sharing E.L.H. Wood’s 1917 inventory with me. (Personal emails, Aug. 20, 2017 and Sept. 11, 2017.) John Hancock’s will is available on Ancestry.com in the Massachusetts, Wills and Probate Records, 1635–1991, Probate Records, Vol. 103, 1860.

10. John Singleton Copley’s 1765 portrait of her husband John is also in the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

11. Peale learned to paint miniatures while studying at Benjamin West’s studio in England. He wrote to West on April 9, 1783: “…I have done more in miniature than in any other manner, because these are more portable and therefore could be kept out of the way of a plundering Enemy.” The Selected Papers of Charles Willson Peale and his Family, vol. 1, ed. Lillian B. Miller, et al. (New Haven & London, Yale University Press), p. 387–88.

12. Peale noted the dates he worked on the portraits in his diary. In addition, John Adams wrote about seeing both miniatures on a visit to Peale’s studio. Because of a wartime shortage of materials, Peale often made many of his own cases and adapted watch crystals to serve as glass. Peale also lacked access to durable pigments—the organic, and very fugitive red lake pigments he used tended to lose saturation with exposure to light. Consequently, many of Peale’s miniatures now look blue and faded. The miniatures of Lydia and her father have retained their original colors and vibrancy—probably because they were kept in storage.

13. There are no records of baby Lydia’s birth, baptism, or death. It is assumed the records were destroyed in the war.

14. John Hancock to Dorothy Hancock, 10 March 1777, http://www.revolutionary-war-and-beyond.com/john-hancock-letter-to-dorothy-hancock-march-10-1777.html.

15. Personal bill recording payment, John Hancock to David Evans, August 11, 1777, Hancock Family Papers, Baker Library, Harvard Business School. For information on the desk, see Nancy Goyne Evans, Windsor-chair Making in America: From Craft Shop to Consumer ( UPNE, 2006), p. 428.

16. The Selected Papers of Charles Willson Peale and his Family, vol. 1, ed. Lillian B. Miller, et al. (New Haven & London, Yale University Press) p. 415n.

17. Two other Peale miniatures known with a background include a 1767 portrait, Matthias and Thomas Bordley, at the Smithsonian American Art Museum in Washington, D.C., and a ca. 1768 Portrait of a Young Boy in the Bayou Bend Collection, Museum of Fine Arts, Houston.

18. Sellers mentions the July 24, 1780 letter in Peale Papers: vol. 1, p. 351n. The June 20, 1784 letter is reproduced on page 412. This letter provides evidence that Lydia died in Philadelphia.

19. A possible candidate for the artist is Joseph Dunkerley, active in Boston at the time. Dunkerley came to America as a British soldier but deserted and joined the Americans in 1778. In 1781 he rented a house from silversmith Paul Revere, who made many of his miniature cases. He later opened a shop on Newbury Street, and in 1786 he moved to a home on Winter Street, directly across the Commons from John Hancock’s mansion. He left Boston in 1788 to live in Jamaica. For more about Dunkerley see the 2016 online article by Michael I. Tormey, Featured Artist: Joseph Dunkerley (1752–1806) at http://www.michaelsmuseum.com/articles/Dunckerley.pdf and the 2014 article by Don N. Hagist, “He’d Rather Be Painting” in the online Journal of the American Revolution at https://allthingsliberty.com/2014/02/hed-rather-be-painting.

20. Charles Coleman Sellers, Charles Willson Peale with patron and populace. vol. 59 (Philadelphia: American Philosophical Society, 1969), p. 61. I have found only these two lockets of this design so far. They are probably European. Further research is being conducted.

21. Robin Jaffee Frank, Love and Loss: American Portrait and Mourning Miniatures (New Haven, Conn: Yale University Art Gallery, 2000), p. 13.