“A Perfect Likeness”: Folk Portraits and Early Photography

American folk portraiture, which flourished in the 1820s and 1830s, was eclipsed by daguerreotypy—the first practical photographic process—when it became available in the 1840s. The reasons for the demise have never been closely examined; only recently have folk portraits been studied as a middle-class commodity and evaluated as tangible examples of social history. This sort of investigation has raised many questions. Why, and how, did daguerreotypy put most folk portraitists out of business? Was it cost, style, or innovation that attracted patrons to the new photographic medium? “A Perfect Likeness”: Folk Portraits and Early Photography, on view at the Fenimore Art Museum in Cooperstown, New York, provides answers to these questions and offers insight into the way first-generation Americans identified and celebrated themselves.

By 1839, when painter and inventor Samuel F. B. Morse (1791–1872) introduced the daguerreotype to America, folk painters Erastus Salisbury Field (1805–1900) and William Matthew Prior (1806–1873) had been successfully taking likenesses in Massachusetts and Maine for about fifteen years; their older counterpart, Ammi Phillips (1788–1865), had been painting portraits in New England and New York State since 1811; and the younger Joseph Whiting Stock (1815–1865) had earned a tolerable living by producing portraits for about seven years in western Massachusetts. In upstate New York, Connecticut native M. W. Hopkins (1789–1844) and his student Noah North (1809–1880) prospered throughout the 1830s, carrying New England artistic traditions further west. These established painters, and hundreds like them, were significantly affected by the introduction of the daguerreotype and their reactions varied. It became clear almost immediately that the daguerreotype would make their painted portraits obsolete, as Americans embraced a way of obtaining what painters and daguerreotypists both called “a perfect likeness.” Some painters stopped their work entirely, and sought new occupations; others adapted their style to try to compete with the daguerreotype likenesses, yet others embraced the new technology and became daguerreotypists themselves. Their decisions were undoubtedly partially based on business concerns, stage of career, and the individual desire for artistic expression.

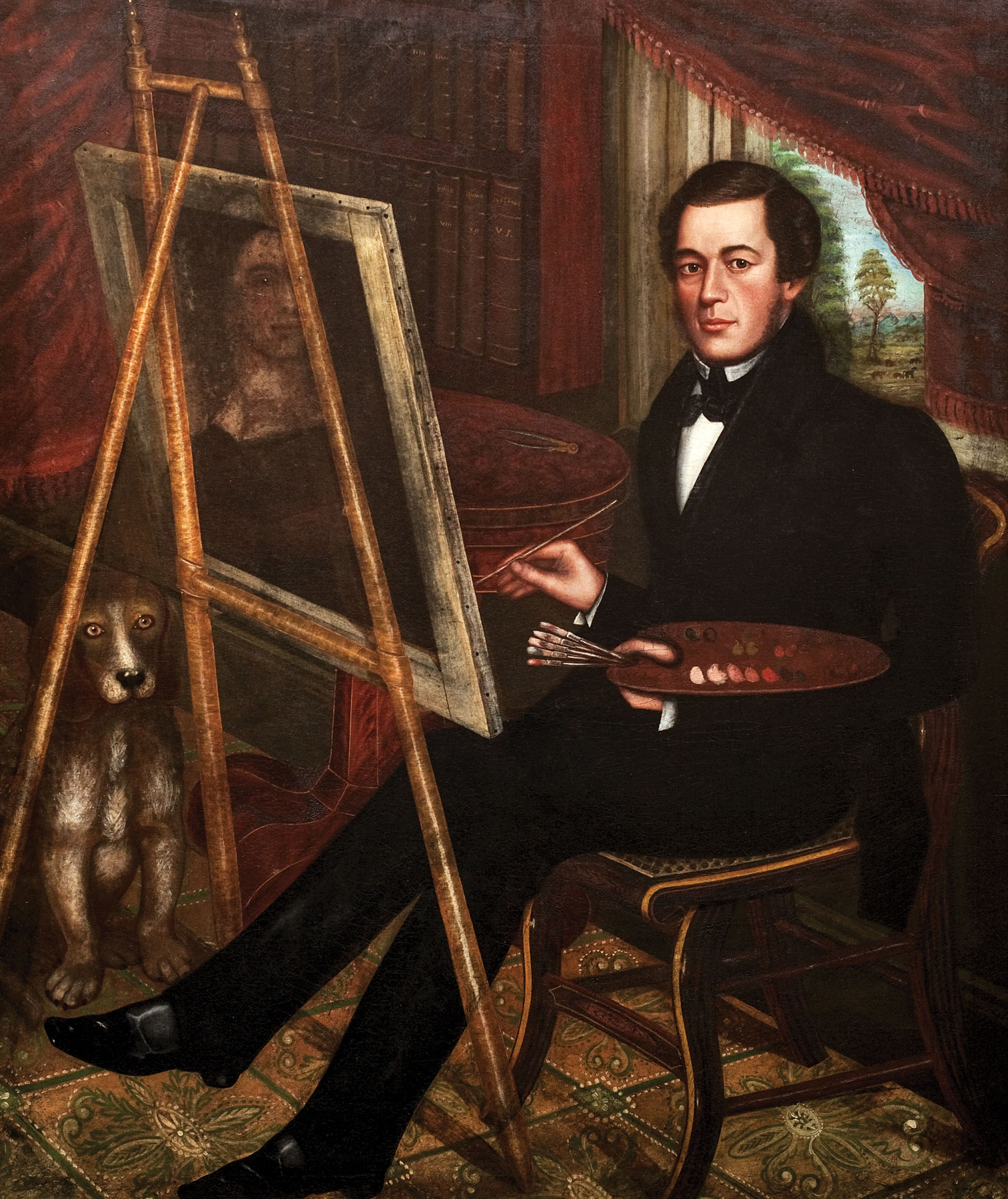

- Randall Palmer (1807–1845), attributed, self-portrait, probably Auburn, N.Y., ca. 1835–1840. Oil on canvas; 59½ x 50 inches. Courtesy of Childs Gallery, Boston, Mass.

Self-portraits by folk painters are rare, and this example offers a treasure trove of information about the artist and his working methods. Monumental in scale and complexity, this painting includes not only a portrait of the artist with his easel, palette, calipers, and brushes, but includes books, bookcase, painted chair and a distinctive dog. A pentimento of a woman’s portrait is seen on the verso of the painting and a landscape can be viewed through an open window. Palmer is known to have worked in Albany, Auburn, Seneca Falls, and Syracuse, doing both large-scale paintings, such as this one, and miniatures. Local histories indicate that he took daguerreotypes in Auburn near the end of his career. His advertisement in a local newspaper in 1841 shows the range of his services: “[Daguerreotypes] are now taken with the greatest accuracy by Mr. Palmer at his “glass house” . . . [he is] ready and happy to wait upon those who may desire to hand down to their posterity their PHIZ [face] upon canvas, ivory, or silver.”

- Robert Peckham (1785–1877), attributed, The Raymond Children, probably Mass., ca. 1838. Oil on canvas; 55¼ x 39 inches. Courtesy of The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, N.Y., USA; Gift of Edgar William and Bernice Chrysler Garbisch (1966.242.27). Image copyright © The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Image source: Art Resource, N.Y.

Massachusetts native Robert Peckham lived and worked in the central part of the state, where he studied briefly with academic artist Ethan Allen Greenwood (1799–1866). He began his artistic career doing house, sign, and ornamental paintings to supplement his work as an aspiring portraitist. Peckham’s large-scale, colorful portraits of prosperous rural families surrounded by their possessions illustrated the consumer goods that had become increasingly available to an upwardly mobile middle class. Anne Elizabeth (b. 1832) and Joseph Estabrook Raymond (b. 1834) were the children of a prominent merchant family from Royalston, a town not far from Peckham’s home in Petersham.

The background of the painting shows the interior details typical of a middle class home in the 1830s: elaborate carpeting, stenciled wall design and an Empire-style table. Like his contemporary M. W. Hopkins, Peckham was an active temperance advocate and Abolitionist.

- Erastus Salisbury Field, (1805–1900), attributed, Mrs. Paul Smith Palmer (Hannah Eells Palmer) and Her Twins, probably Stockbridge, Mass., ca. 1835/1838. Oil on canvas; 38½ x 34 inches. Courtesy of the National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.; Gift of Edgar William and Bernice Chrysler Garbisch (1971.83.5).

In 1836, Field journeyed from his home near Leverett, Massachusetts, to the hill towns of Berkshire County in search of new portrait commissions. Many likenesses from this period and area have been discovered. Paul Smith Palmer (1796–1875), a native of Connecticut, moved to Stockbridge in 1805, where he married his cousin, Hannah Eells Palmer (1804–1891) in 1824. The couple settled on a farm and had nine children, only three of whom survived to adulthood. The twins shown here, Charles and Emma, were born in 1835 and both died in 1838. Twins may have held a special fascination and fondness for Field because he himself was a twin.

By the late-1850s, Field was painting in Palmer, Massachusetts, where he portrayed local citizens who came to his studio. These figures, however, are quite different from the ones who dominated his canvases prior to 1850. Somewhere, possibly in New York City, he had learned from his old teacher, Samuel F. B. Morse, the use of the camera, and from that point forward, he used photographs as the basis for almost all of his portraits. He posed and photographed his subjects, then enlarged the results on canvas in color. Figures are surrounded by empty spaces and groups are shown in elaborate Victorian settings. In every case, the subjects are portrayed as small groups, rather than as individual portraits. Deacon Wilson Brainerd (1806–1881) served in the Second Congregational Church of Palmer, with which Field was affiliated. Included are Brainerd’s wife and sons, two of whom were deceased at the time that Field created this likeness. The posthumous figures were undoubtedly copied from existing photographs. An examination of Field’s late work reveals that photography clearly undermined the artist’s creativity; he would never again produce the lively and colorful portraits that characterized his early career.

Noah North’s portrait of Eunice Spafford (1778–1860), done when she was fifty-five years old, and he was aged twenty-five, was painted in Holley, New York, a town on the Erie Canal, some twenty-five miles east of Rochester. It was a short journey for the young artist from his home in nearby Alexander, and just a few miles by canal packet boat from the home of his mentor, M. W. Hopkins, in Albion. North used a somber palette in his depiction of Mrs. Spafford. The grain-painted chair with real stenciled designs of melons, leaves, and other stylized floral motifs indicates that he was skilled in the technique of stenciling with gold powders, and suggests that he learned the art of furniture decoration, in addition to portrait painting, from his teacher, Hopkins, who offered lessons in both crafts in the early 1830s. North painted several members of the family at approximately the same time, including Elizabeth Powers Darrow (1805–1874), whose portrait is included in the exhibition. North traveled to Ohio with Hopkins in the late-1830s, but by 1841, he had returned to New York State, where he took up daguerreotypy with only moderate success.

This portrait of Pierrepont Edward Lacey (1832–1888), nearly full-size, is one of the most ambitious and engaging likenesses taken by Connecticut native M. W. Hopkins, and has become a folk art icon. Solid and sturdy, the young boy, dressed in his best suit and bolstered by his huge dog, looks out candidly to the viewer. Animals in folk paintings were often the products of the artist’s imagination or copied from popular illustrations, but “Gun” was a real pet. According to family history, the Laceys raised mastiffs when they lived in Scottsville, a few miles south of Rochester. Hopkins, who painted portraits in upstate New York and Ohio in the 1830s and 1840s, often depicted sitters who were involved in reform movements of the day and shared his progressive values. Pierrepont’s father was a successful farmer and businessman who was active in the Anti-Masonic movement and Whig politics, as was Hopkins, and it is likely that they became acquainted through these associations. In addition, Hopkins painted Pierrepont’s mother, sister, and father, as well. After painting in the Rochester area in the mid-1830s, Hopkins moved to Ohio, taking his student Noah North, where they advertised as portrait painters in Cleveland, Columbus, and Cincinnati, for a few years. At the time of his death in 1844, Hopkins was a major participant in the Underground Railroad network, helping to bring slaves from the south to the free state of Ohio.

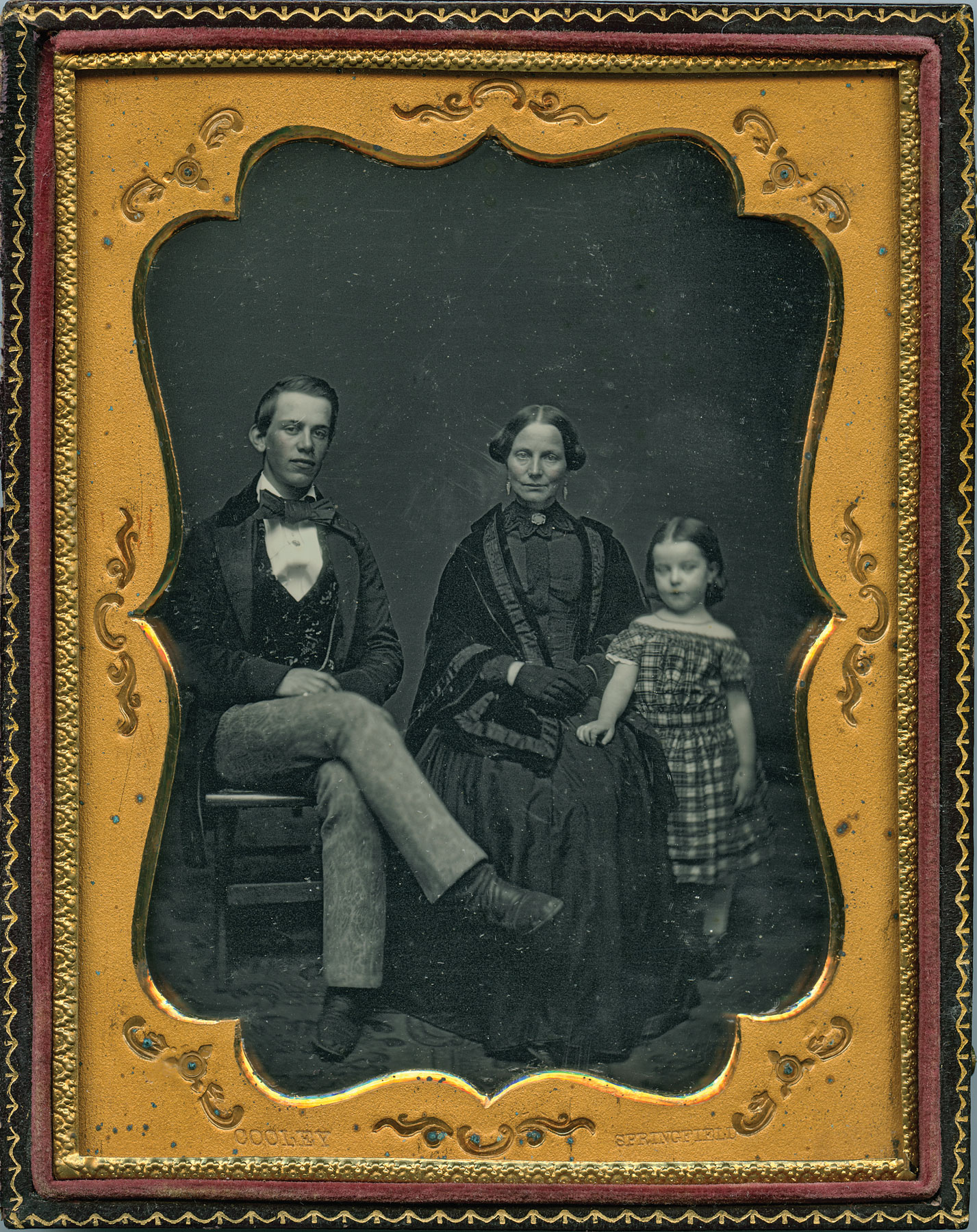

The life of Joseph Whiting Stock, a Massachusetts native, is one of the most remarkable in American folk art history. He successfully overcame the debilitating injuries of a childhood accident and burns from a fire to earn a tolerable living as a painter. Working from a custom-designed chair, Stock traveled through southern New England, taking almost one thousand likenesses in a twenty-year period. The portrait of Jane Henrietta, considered by some to be Stock’s masterpiece, was done, according to a journal kept by the artist, “from corpse,” as a remembrance of a life that ended much too early. In the mid-1840s, Stock formed a partnership with his brother-in-law, Otis Hubbard Cooley (1820–after 1855) in Springfield, where Stock produced miniature paintings and Cooley took daguerreotypes. Stock has included two daguerreotype, or miniature portrait, cases in Jane Henrietta’s composition, which may be a visual clue pointing to other images of the little girl.

In 1845, in Springfield, Massachusetts, Joseph Whiting Stock, in partnership with his brother-in-law, Otis H. Cooley, offered a variety of artistic services, with Cooley taking daguerreotypes and Stock painting miniature portraits. Their advertisement in a Springfield newspaper stated: “Stock and Cooley have re-opened their Gallery . . . and respectfully invite the attention of the public to their collection of paintings and photographs . . . Mr. S. [Stock] has had much experience painting from the corpse and orders on this and adjoining towns will be promptly attended to . . . instructions given in Drawing and Oil Painting . . .” This daguerreotype, with Cooley’s stamp, shows what appear to be a mother, son, and daughter, all dressed in typical 1840s garb. The little girl shown in a plaid dress is identical to many seen in painted portraits of the same period.

To compete with daguerreotypists in Boston, and to satisfy customers seeking a symbol of respectability and social status, Prior produced many of his most visually engaging paintings in the 1840s and 1850s. Highly decorative, full-scale images of children, accompanied by playthings and pets, displayed the artist’s versatility and the personalities of his young sitters. This portrait of an unidentified child standing beside a huge dog is one of Prior’s more complex and enigmatic compositions. The artist has successfully captured the facial features of the small child, who gazes directly at the viewer; the alert dog, probably a family pet, is almost as important as the child in the scene. The gender of the child is uncertain, as both girls and boys typically wore dresses and feathered hats. The coral necklace and bracelet—talisman to ward off evil spirits—were generally feminine accessories. The whip, however, is commonly seen only in portraits of boys, and the inclusion of a table knife has puzzled scholars for decades.

The two boys, who appear to be twins, hold stuffed dog pull toys—playthings often seen in folk paintings. The boys posed, apparently none too happily, for the daguerreotypist, wearing their best suits of clothing.

Scholars have identified at least four hundred paintings by Jeremiah P. Hardy done in the Bangor, Maine, area between the 1820s and the early 1880s. In this portrait, painted relatively early in Hardy’s career, he depicts Abraham Hanson, a barber who worked in Bangor, Maine, in the 1820s and 1830s. Hanson is shown in a relatively casual and relaxed manner, gazing directly at the viewer and making an engaging and intimate connection. It appears that Hardy captured his sitter’s personality perfectly. In an early history of Bangor, Hanson is described as: “[Possessing] much humor . . . and afforded amusement to his customers . . . [He] was well-patronized and deemed worthy to have his portrait painted by Hardy.”

During the 1850s, Hardy and his son worked as daguerreotypists. The subjects of this daguerreotype, Timothy (1793–1872) and Lucy Heywood (1800–1866) Crosby, were also pictured by Hardy in a painting. The Crosby family was among the first settlers of Bangor, coming from Duxbury, Massachusetts. Timothy was a farmer and successful businessman who owned shares in several sailing vessels in Bangor.

Given its history of ownership in Boston, it is likely that this daguerreotype was done at Plumbe’s studio in Boston in the mid-1840s. The compelling likeness shows a fashionable young mother with her arm protectively encircling her son, who is dressed in his best clothing. The Boston studio was one of fourteen that Plumbe franchised during the 1840s. He was awarded the silver medal for daguerreotypy in 1844 at the Massachusetts Charitable Association Fair in Boston.

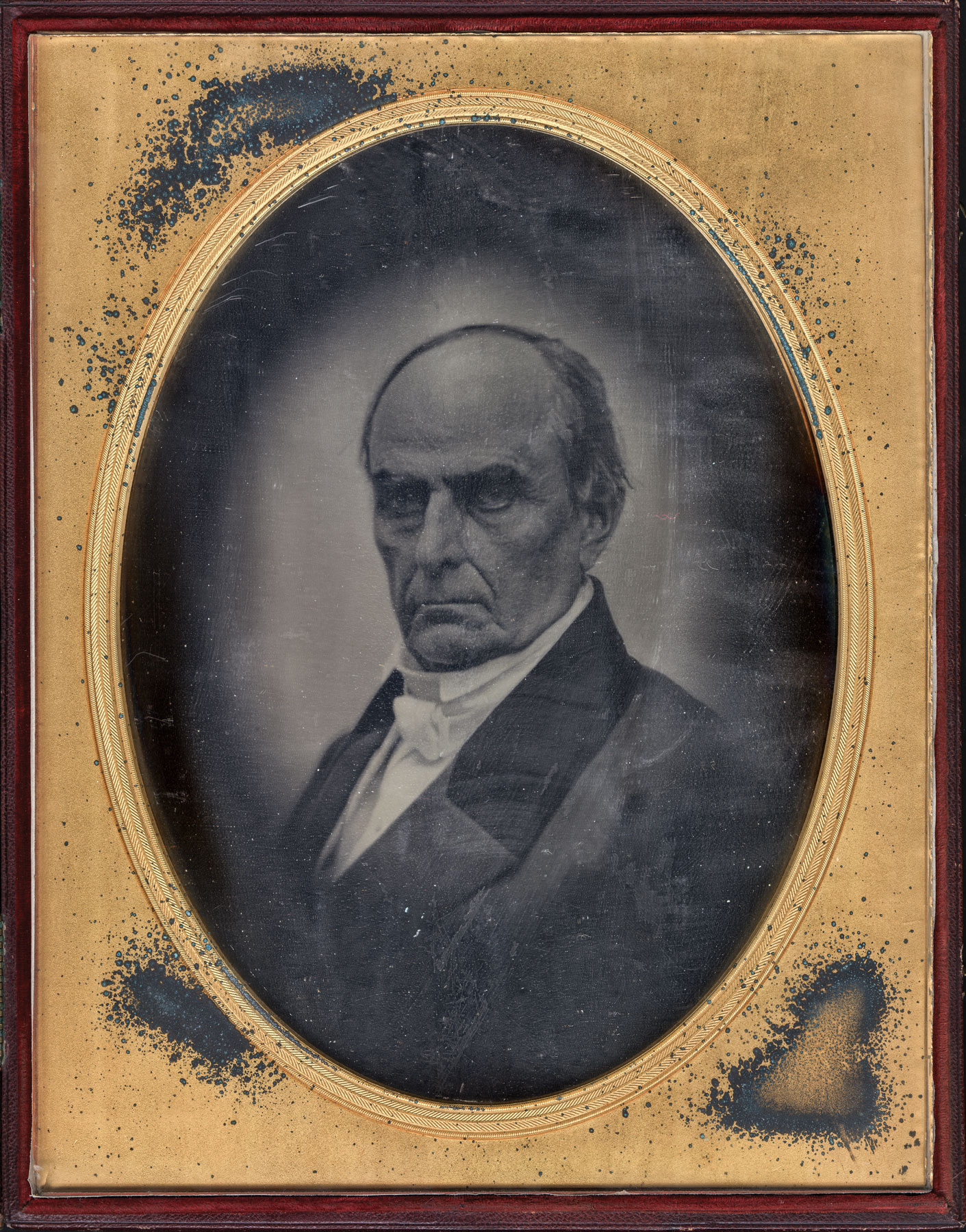

- Albert Sands Southworth (1811–1894) and Josiah Johnson Hawes (1808–1901), Daniel Webster, Boston, Mass., 1851. Whole-plate daguerreotype. Inscribed on case: “This is the last likeness of MR. WEBSTER taken while living and was made for JOHN E KENDALL of Boston in 1851.” Courtesy of Massachusetts Historical Society, Boston, Mass., Daguerreotype collection (1.377L).

Daniel Webster (1782–1852)—lawyer, senator and distinguished orator—also served as secretary of state under Presidents William Henry Harrison, John Tyler, and Millard Fillmore. One of the most influential and well-known politicians of the nineteenth century, he sat for Southworth & Hawes at least ten times. Upon his death in 1853, a Boston newspaper noted: “At artists [Southworth & Hawes] Daguerreotype rooms . . . may be seen several daguerreotypes taken from life, at different periods, of the great statesman whose loss the nation so deeply mourns.”

Samuel F. B. Morse, who, by the mid-1830s had abandoned his painting career for that of an inventor, was in Paris seeking a French patent for his electro-magnetic telegraph, when he met Louis Jacques Mande Daguerre (1789–1851). Daguerre had invented a method of producing, in full sunlight, a small monochromatic image fixed permanently on a plate of silvered copper, which he named after himself. Morse instantly recognized the invention as revolutionary and learned the method from Daguerre. Arguably the first American to see a daguerreotype, Morse wrote to his brother, then the editor of The New York Observer, “[The daguerreotype] . . . is Rembrandt perfected. No painting or engraving ever approached it!”

Morse’s observation was soon reprinted in newspapers throughout America, building anticipation for the arrival of the daguerreotype in this country. He brought the details of the process with him when he returned from France in 1839, and soon began giving demonstrations of the innovative process and instructions on how to use it. Numerous early adopters did likewise, hoping to exploit the public curiosity that had been piqued by the newspaper accounts. Daguerreotypy became so popular that, throughout the decade of the 1840s, it’s estimated that amateurs and professionals alike produced almost three million likenesses a year. In Europe, most images were of outdoor scenes; in America, 95 percent of the daguerreotypes were portraits.

The lower cost of daguerreotypes (one dollar and under in some cases, versus ten dollars for a painting), which made them available to more middle-class Americans, played a considerable part in the demise of folk portraiture. A desire for innovation, too, prompted patrons to choose the daguerreotype instead of a painted portrait. The introduction of the daguerreotype coincided with a period of extraordinary technological change and Americans eagerly sought new products that represented the up-to-date.

From many first-person accounts, it is clear that most people were thrilled to have a daguerreotype likeness. Others found them too startlingly realistic, disliking their own images (“flaws” could be improved with paint but were exposed through the new medium). Many amateur efforts, some produced with only a desire for “easy money,” were created with little or no knowledge of traditional aesthetics or methodology. Artistry came with the development of the professional studios, most notably those of Mathew Brady (1822–1896) in Washington, D.C. and New York City; John Plumbe Jr. (1809–1857), who opened a franchise chain of daguerrean studios in fourteen cities; and Albert Sands Southworth (1811–1894) and Josiah Johnson Hawes (1808–1901), who, operating under the business name of Southworth & Hawes in Boston, were the first to use sophisticated lighting effects, facial expressions and gestures, and elaborate scenery and props.

Like the folk portraits it replaced, the daguerreotype had succumbed to new technologies and changing taste by the 1860s. The ambrotype, an image made on glass; the ferrotype, more commonly known as a tintype; paper cartes-de-visite, and other processes that served as the precursors to film photography, gradually replaced the daguerreotype.

Out of hundreds of folk painters working in the early nineteenth century, only a few continued to paint after the invention of the daguerreotype. Erastus Salisbury Field and William Matthew Prior continued to earn a living solely by the brush. Field experimented with photography but, later in his career, concentrated on historical and religious paintings, which replaced the powerful portraits he had produced as a young man. William Matthew Prior, having adjusted his fees on a sliding scale throughout his career, responded to the competition from photography by creating colorful full-scale paintings, particularly of children. He later drew on his skills as an ornamental painter by producing landscapes and scenes copied from popular prints or from his own imagination. Both Field and Prior sold generic likenesses of famous Americans late in their careers.

Many of the artists represented in this exhibition illustrate a typical pattern. Horace Bundy (1814–1883), who painted mainly in Vermont and New Hampshire, continued to paint likenesses on a limited basis, but concentrated on his mission as an Adventist preacher. Miniature portraitist Justus Dalee (1793–1878) gave up painting and went into the grocery business; Ammi Phillips used photographs as patterns for his paintings with limited success; Maine painter Royall Brewster Smith (1801–1855) became a carpenter and house painter; miniature painter Rufus Porter (1792–1884) continued to decorate houses all over New England with his elaborate murals and achieved fame by founding and editing the magazine Scientific American.

Of the painters who attempted to become daguerreotypists—Samuel P. Howes (1806–1881) in Massachusetts; Jeremiah P. Hardy (1800–1881) in Maine; Noah North (1809–1880) in New York State; and Randall Palmer (1807–1845) in central New York, were only marginally successful and eventually turned to other occupations.

As the century progressed, romantic portraits by academically trained artists and landscape painting—prompted by western exploration and settlement—captured the fancy of the art world. Photography became the chosen medium for likenesses for the middle class and the painted portrait returned to its origins as a commodity for the elite. Through a combination of factors—economic, scientific, and cultural—folk portraiture, which had represented a type of status and gentility for many Americans, succumbed to technology and changing taste and never flourished again.

“A Perfect Likeness”: Folk Portraits and Early Photography is on view at the Fenimore Art Museum, Cooperstown, New York, until December 31. For information visit www.fenimoreartmuseum.org or call 607.547.1420.

Jacquelyn Oak, guest curator of the exhibition, works in the education department of the Shelburne Museum, Vermont.

This article was originally published in the Winter 2015 issue of Antiques & Fine Art magazine, a digitized version of which is available on afamag.com. Antiques & Fine Art and AFAmag are affiliated with InCollect.com.

_.jpg)