A Woman Lithographer in Nineteenth-Century New York

A WINTERTHUR PRIMER

Frances Flora Bond Palmer (1812–1876) is the most important woman lithographer of nineteenth-century America. She is best known for her association with Currier & Ives, where, after joining the firm in 1851, she produced more prints than any other artist. Before then, Palmer held an independent career both in England and in New York, where she settled with her family in 1844.1 She exhibited at the National Academy of Design and the American Institute, executed dozens of framing prints, and created the lithographs for several illustrated books.2 Winterthur’s museum and library collections hold several examples of her early American work. Looking at these lithographic prints created before her long collaboration with Currier & Ives gives us insight into her position as an artist lithographer in nineteenth-century New York, and her contributions to the expanding field of American lithography.

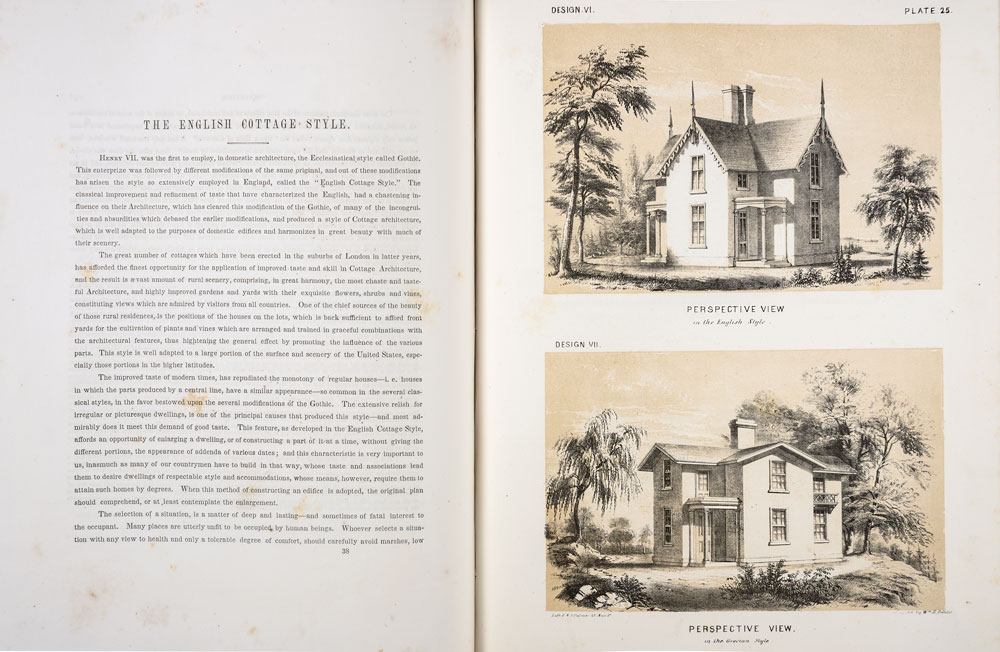

One of the largest of Palmer’s early New York commissions consisted of the lithographs that reproduced William H. Ranlett’s architectural drawings of site views, elevations, and floor plans for Ranlett’s two-volume book The Architect, published in New York between 1847 and 1849 (Fig. 1). In this publication, Palmer used a two-stone lithographic technique that reflects her training with Louis Haghe (1806–1885), one of the founders of Day & Haghe, the leading lithographic firm of early Victorian London.

Haghe was a famous architectural draftsman, a watercolor artist, and the lithographer of David Roberts’ watercolor drawings for The Holy Land, Syria, Idumea, Arabia, Egypt and Nubia (1842–1846), widely considered the culmination of Haghe’s tinted lithographic technique. Palmer was in Haghe’s workshop during the early stages of the preparation of Roberts’ watercolors. She, in turn, brought to Day & Haghe an excellent foundation in drawing, perspective, and watercolors learned at Mary Linwood’s academy for girls in Leicester. With Haghe, Palmer perfected her knowledge of drawing and drafting, and mastered the technique of tinted lithography. Combining a stone with crayon drawing with another stone of monochrome tint, a tinted lithograph could imitate the effect of the watercolor wash often used in the background of a drawing.

Church of the Holy Trinity (Fig. 2), another early New York print by Palmer, shows the artist’s mastery of multiple-stone lithographic technique. Here, Palmer prepared one tint stone with a broad expanse of solid blue tone for the sky, with small areas removed or “gummed out” to create the white clouds. Instead of limiting her use of secondary stones to tint—the lithographic imitation of watercolor washes—she created two crayon drawings on two separate stones. One was printed in black, to delineate the contours and architectural details of the church. The second one, printed in brown ink, highlighted the texture of the church’s stonework and enhanced the dramatic effect of the sunlight on the ornate facade of the Gothic Revival architecture.

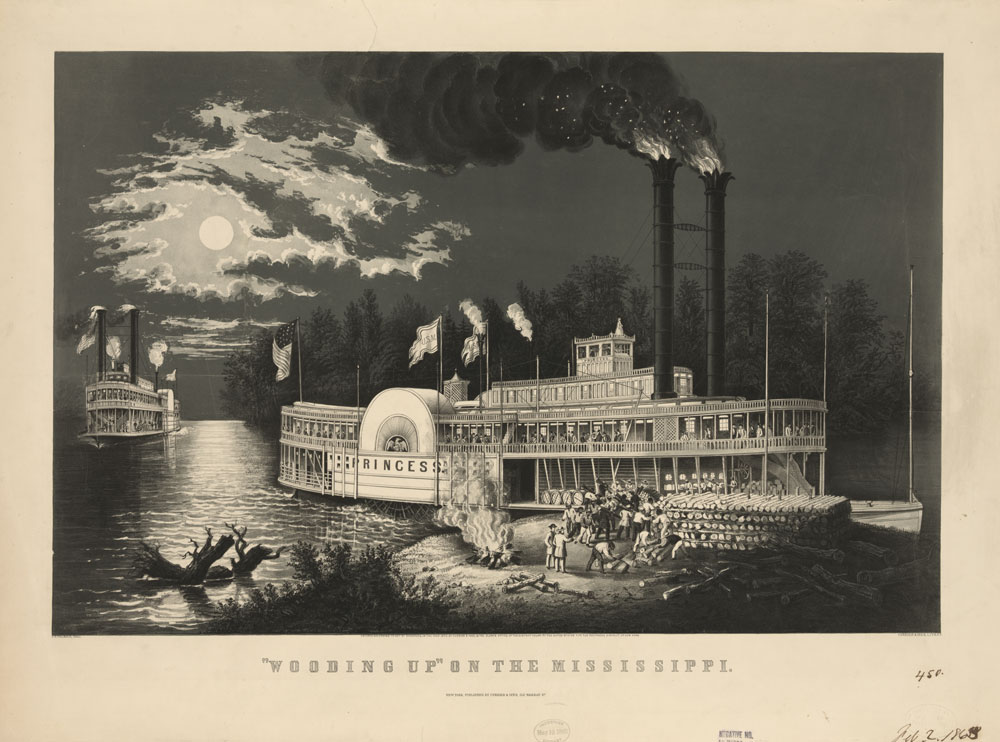

A closer look at Palmer’s early work in New York calls attention to her role in the development of American lithography in the 1850s. More specifically, her fine use of multiple stones in the drawing of Church of the Holy Trinity suggests that she had a critical influence at Currier & Ives. Nathaniel Currier almost entirely limited his publications to black and white lithographs before hiring her. After 1851, the firm published several of their now iconic compositions, drawn by Palmer and printed with more than one stone. One of them, Wooding-Up on the Mississippi (Fig. 3), reveals how her brilliant handling of tonal values created a nocturne landscape that barely needs the addition of hand coloring that we expect to see on a Currier & Ives print.

Palmer is one of the artists whose work is explored in Lasting Impressions: The Artists of Currier & Ives, at Winterthur Museum, from September 17, 2016, until January 8, 2017.

-----

Marie-Stephanie Delamaire is associate curator, fine arts, Winterthur Museum, Garden & Library, Winterthur, Delaware.

More Winterthur Primer articles are available on Incollect. Visit www.Winterthur.org for a full listing.

This article was originally published in the Autumn 2016 issue of Antiques & Fine Art magazine, a fully digitized version of which is available at afamag.com. AFA is affiliated with Incollect.

2. Charlotte Streifer Rubinstein, Fanny Palmer: Artist to the American People, forthcoming, 2017. See also her article, “The Early Career of Frances Flora Bond Palmer (1812–1876) in The American Art Journal 17, No. 4 (Autumn 1985), 71-88.