American Impressionism in a New York Townhouse

“Collecting is a shared passion,”

—Ken Landis says of the pastime he enjoys with his wife, Rosalind.

I’m from Edinburgh, so Robert Adam is the gold standard for me,” says Rosalind Landis, recalling the day six years ago that she and her husband, Ken, happened upon a 1921 Manhattan townhouse whose neoclassical details instantly reminded her of Scotland’s most famous architect and the leader of the classical revival movement in eighteenth-century England.

The purchase of the five-story, limestone-faced dwelling designed by Lucian E. Smith, an Illinois-born architect who studied at the American Academy in Rome before briefly working with Cass Gilbert (1859–1934), marked the beginning of a rewarding journey during which the Landises honed their collection of eighteenth-century English and French furniture and Chinese export porcelain, and developed a passion for paintings by American artists who lived and worked in France at the turn of the twentieth century.

“This house had the right configurations for our needs and was in very good condition. Nevertheless, it required a great deal of work,” recalls Rosalind, who approached the project with the same talent and determination she displayed as president of Bobbi Brown Cosmetics, Inc., the company she and Ken co-founded in 1990 with Brown, a friend and former freelance makeup artist. (Estée Lauder acquired the business in 1995.)

On a holiday shopping trip to London, where the Landises met years earlier, the collectors bought their first antiques for their new house, whose ample interiors, remodeled by Beringer Architects of New York, are bathed in soft light and accented with medallions, swags, and urns. Well-placed alcoves and niches, some added at the couple’s request, hold sculpture.

“Adam Style by Steven Parissien and The Work of Robert Adam by Geoffrey Beard inspired our interior design,” says Rosalind, who, in collaboration with W. D. Interiors of Greenwich, Connecticut, chose for the existing entryway ceiling a palette of Adam-inspired mineral green, blue, ochre and cream, colors she remembered from childhood, from places such as Oxenfoord Castle, modernized by Adam in 1780, and Hopetoun House, the site of several exuberant Scottish balls that she attended as a girl.

At Chesney’s, the famed London supplier of antique chimneypieces, the Landises found for their entrance hall an eighteenth- century English carved fireplace surround, inset with delectable toffee-colored sienna marble panels. For the living room, a floor above, they bought a neoclassical English statuary marble chimneypiece. “We were very nervous about the chimneypieces fitting, but they were perfect,” says Ken, an investor who is COO of the Accessory Network Group.

Before the shopping spree was over, the Landises had also acquired a George III breakfront bookcase of lustrous mahogany and a circa-1770 Hepplewhite linen press from Adrian Butterworth of Butterworth & Zock Ltd. The London dealer in English furniture, who continues to advise the Landises, led them to the perfect overmantel mirror for above the mantel in the entryway, a circa-1770 borderglass example discovered at Ossowski, the Pimlico Road specialists in eighteenth-century gilt mirrors, carvings, and furniture. A similar collaboration with Abby Taylor and Vincent Vallarino of the Greenwich Gallery in Greenwich, Connecticut, resulted in the couple’s collection of American impressionist and Boston School paintings.

“Starting a collection is not like studying art history,” says Rosalind, who earned a master’s degree from the University of Aberdeen, Scotland, studied fine art and antiques at Sotheby’s Institute in London, and once contemplated a career in the arts. “You don’t know where you are going when you begin collecting. You just know that you must love a piece to live with it.”

Both husband and wife were instinctively drawn to the American painter Frederick Carl Frieseke (1874–1939), who arrived in Paris in 1898 and briefly studied with James Abbott McNeill Whistler before becoming a central figure in the Giverny art colony after 1906. One of the collectors’ favorite possessions, Frieseke’s After the Bath, a postimpressionist treatment of a dramatically cropped nude, hangs over the living room fireplace.

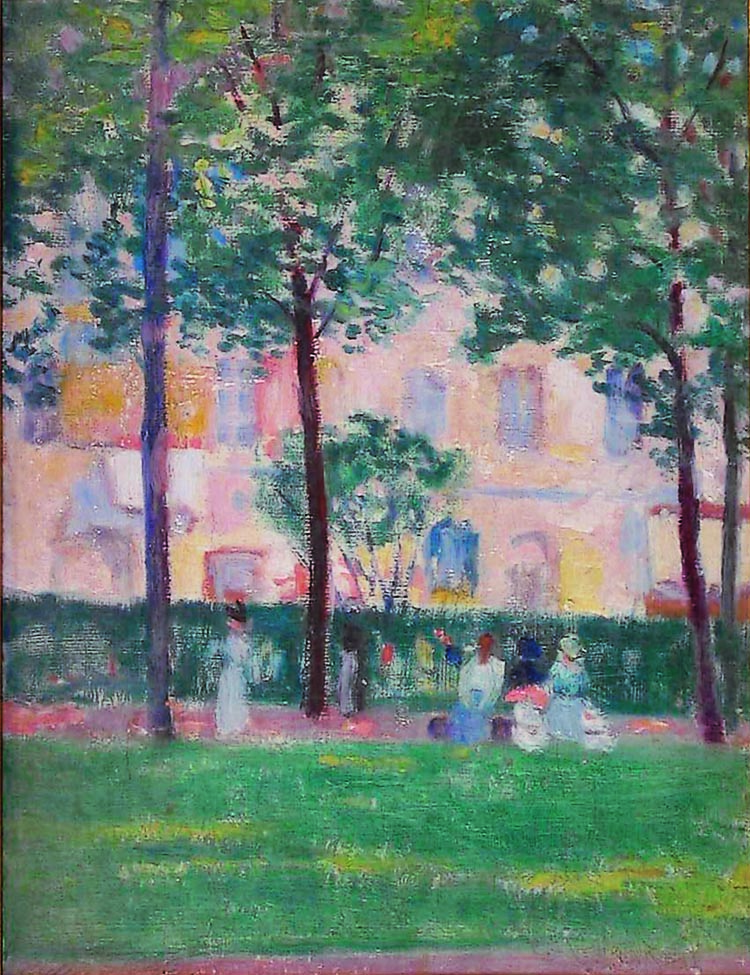

“Ken and Rosalind have always had their own opinions, but they’re interested in learning more. If we gave them material to read, they mastered it overnight. They have become very knowledgeable. We have a real exchange of ideas and a relationship of mutual respect,” says Abby Taylor, describing what might be the ideal client. With the couple’s affinity for Frieseke in mind, Vallarino and Taylor presented their clients with Monet’s Giverny: An Impressionist Colony (1993) by art historian William H. Gerdts. “It greatly influenced our collecting,” says Rosalind, who prizes the sense of intimacy and masterfully rendered light that characterizes many of the views of beautiful women in contemplation that grace the walls of the Landis home. In the living room, three painters who admired each other in life continue their conversation on canvas. Hanging opposite Frieseke’s Bath is Reverie by Richard Edward Miller (1875–1957), a circa 1910–15 portrait of a reposing woman. Nearby is Giverny Garden, painted in energetic dashes by Louis Ritman (1889–1963) in Frieseke’s garden. Complementing the Ritman painting is famille rose porcelain of a similar pastel palette and the same broken brushwork. The warm tone of the room is further enhanced by gilded and inlaid satinwood French and English furniture. A pale Aubusson carpet of 1840 pulls it all together. Rosalind sighs, “The carpet is not the most practical but it just had to be.”

Two intimate Frieseke watercolors join two works by Louis Kronberg (1872– 1965) in the master bedroom, a cool study in soft blue and oyster white. “It’s just so dreamy,” Rosalind says of her favorite of the two Kronbergs, Repose, a pastel on canvas nude executed in 1909 by the Boston-born painter who spent much of his career in France.

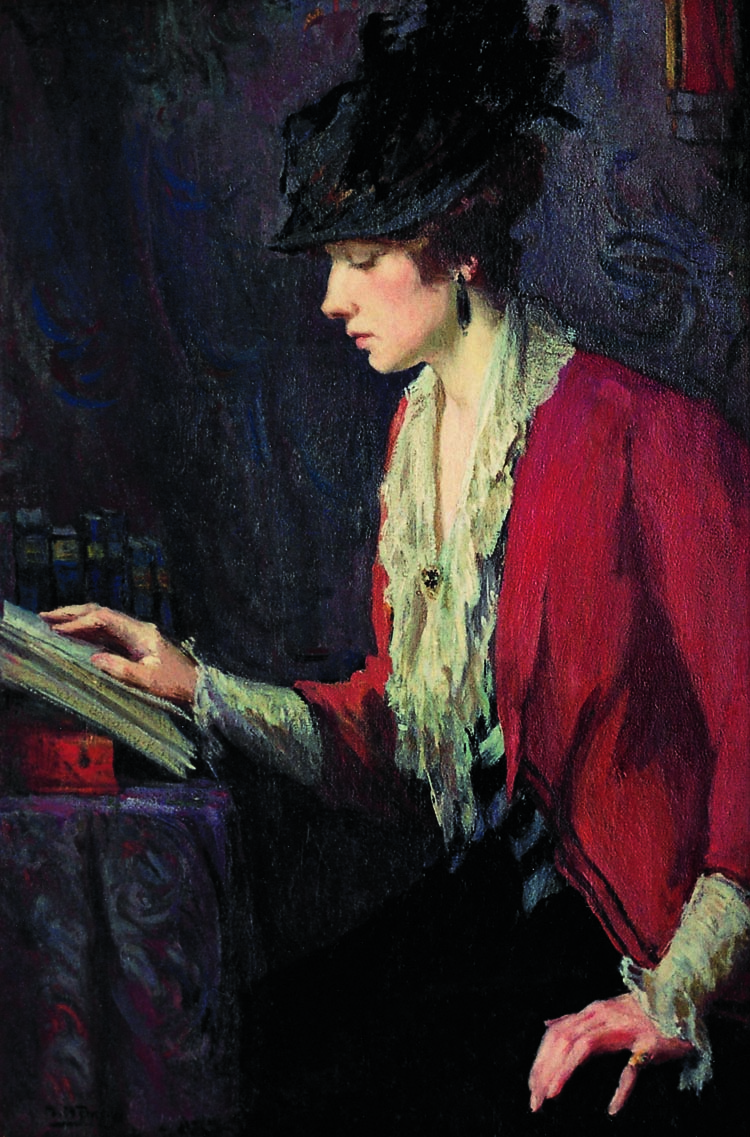

“We never set out to collect Boston School portraits but these strong, handsome women make such nice company,” says Rosalind, leading her guests into a dining room lined in crimson colored cut-velvet, a wall covering manufactured from a sample in Scalamandre’s archives. With the lights dimmed and the circa-1850 English cut-crystal chandelier, from Florian Papp, lit, it is easy to imagine the Boston salon of the Brahmin doyenne of the same era, Isabella Stewart Gardner.

More traditional than the Giverny circle, Boston School painters like Edmund Tarbell (1862–1938) and Frank Benson (1862–1951) painted psychologically acute portraits, often of women in interior settings, that owe as much to Vermeer as Monet. “The textures, the color, and the light make this painting very special,” Vincent Vallarino says of The Old Fashioned Gown, a moody study in gold and lavender by Tarbell-student Mary Rosamond Coolidge (1884–1978) that hangs in the dining room. Nearby hang portraits by Mary Bradish Titcomb (1856–1927), another important Boston painter; Ivan Gregorewitch Olinsky (1878–1962), and Pauline Lennards Palmer (1867–1938).

“In time we felt a need for texture and dimension,” says the couple, explaining their interest in sculpture. They were drawn to the female form in late-classical French sculpture that, like the paintings the Landises own, suggests the first fluttering of modernism. The Landis collection contains marble and bronze sculptures by Emile-Andre Boisseau (1842–1923), Jean Alexander Falguière (1831–1900), and Alfred Boucher (1850–1934). Volubilis, a naturalistically carved marble nude by Boucher, “is a timeless work by one of the great sculptors of the turn of the century,” says Abby Taylor.

In matters of taste the Landises usually agree. But not always. “I was floored,” confesses Rosalind, recalling Ken’s initial objection to The Chocolate Girl by Henri Guillame Schlesinger (1814–1893). She acknowledges that, with its early date of 1873, the oil on canvas by the French artist was a bit of a departure for them. Ken grew to appreciate the portrait of the young pantry maid with a mischievous glint in her eyes that now hangs in their cozy, antique-pine paneled study.

The Landis collection is almost complete. These days, only a spectacularly rare or special painting or sculpture will tempt the collectors, who continue to look for a Gainsborough chair and an inlaid satinwood serving tray for the living room, and who may replace a few pieces of furniture in the dining room.

“Collecting is such an accidental, happy thing. As a hobby, it’s been pure delight for us,” says Rosalind. Whether building a business or a collection, this art-loving couple believes that collaborating with experts makes all the difference.