An Extraordinary Legacy: John J. Snyder Jr. and Early Lancaster County Decorative Arts

|

Rock Ford Plantation, home of General Edward Hand (1744–1802), Lancaster, Pa. A native of Ireland, Edward Hand received his medical training at Trinity College in Dublin, and by 1774 had settled in Lancaster, Pennsylvania. The following year, he married Katherine Ewing; the couple had eight children. Hand served in the Continental Army and became adjutant general in 1781. After the war, he returned to Lancaster and became active in politics. In 1794 he retired to Rock Ford, an elegant country seat just south of Lancaster Borough. |

An outstanding scholar and collector of Pennsylvania decorative arts, John J. Snyder Jr. left an extraordinary legacy when he died in late 2013 at age sixty-seven. During his lifetime, he amassed an incredible collection of tall clocks, furniture, silver, and paintings. These objects overflowed the rooms of Toad Hall—John’s nickname for the 1813 Federal brick mansion he meticulously restored along the Susquehanna River in Washington Boro, Pennsylvania — as well as a two-story garage and the lower level of a large bank barn. In later years, John even outfitted the rooms at his nursing home with antique furniture. Most of his collection was from southeastern Pennsylvania and particularly Lancaster County, whose “weird but wonderful” furniture, as John lovingly referred to it, captivated his attention even as a young man. In the mid-1970s, John upended longstanding assumptions about Lancaster County furniture in a series of articles debunking attributions of Lancaster rococo furniture to the Bachman family while providing alternative, and thoroughly documented, attributions to other craftsmen. This culminated in his thesis “Chippendale Furniture of Lancaster County, Pennsylvania, 1760–1810,” completed for the Winterthur Program in Early American Culture in 1976.1 He also wrote important studies of Lancaster and Berks County clock cases.2 In later years, John turned his keen eye onto Lancaster Federal furniture and especially the Manheim workshop of cabinetmaker Emanuel Deyer, of whose work John accumulated numerous examples.

Visits with John were truly unforgettable. He had an infallible memory that enabled him to recall even minute details about furniture construction or a cabinetmaker’s inventory. John also had an insatiable curiosity — always demanding to know about any new discoveries related to Pennsylvania furniture. He was also a dedicated public servant, helping to found both the Heritage Center of Lancaster County and the Historic Preservation Trust of Lancaster County. John also dedicated himself to Rock Ford Plantation, just south of Lancaster, as a long-time board member and collections committee chair to guide its restoration and furnishing. In a final act of generosity, John’s collection was donated to numerous regional museums — including the Berks History Center, Cumberland County Historical Society, Lancaster Mennonite Historical Society, Landis Valley Museum, York County History Center, and The Speaker’s House, as well as Winterthur. The largest portion of John’s collection — including 32 tall clocks, 63 other pieces of furniture, 62 silver objects, and 17 paintings — was donated to Rock Ford Plantation, where fundraising efforts are now underway to convert an existing Pennsylvania German bank barn into a display space. Projected to open in 2020, the John J. Snyder Jr. Gallery of Early Lancaster County Decorative Arts will share this extraordinary legacy for generations to come. Visit RockfordPlantation.org to learn more.

|

|  |

Chest (and detail), Lancaster County, Pa., ca. 1750. Walnut, yellow pine, iron. H. 24¾ W. 53⅜, D. 23⅛ in.

One of the earliest objects in the Snyder collection, this walnut chest dates to the mid-1700s based on its paneled lid and baroque carved ornament (the bracket feet are later replacements). Consisting of two nearly identical front panels, the carving is rendered from the solid wood in typical Germanic fashion. Closely related carving appears on the door of a schrank also thought to be from Lancaster County.3 | |

|

|

Tall clock (and detail), made for Christian Schwar (n.d.), movement attributed to George Hoff (1733–1816), Lancaster, Lancaster County, Pa., 1766. Walnut with sulfur inlay and tulip poplar. H. 107, W. 19¼, D. 11 in. The pediment of this clock is inlaid in sulfur with the name of Christian Schwar, a Mennonite farmer in East Hempfield Township. The inlay designs and overall form place the clock within the earliest known group of sulfur-inlaid furniture, which appears to have originated in or near Lancaster Borough.4 Although unsigned, the clock movement is firmly attributed to George Hoff, a German immigrant and one of the most influential clockmakers in Lancaster. |

|

|

Miniature chest, Manheim, Lancaster County, Pa., ca. 1780–1800. Walnut, tulip poplar, brass. H. 11⅛, W. 16⅞, D. 9½ in. This diminutive walnut chest is ornamented with shells and foliate tendrils carved in slight relief on the facade, as opposed to the bolder, heavier Lancaster rococo carving. The chest is thought to have originated in Manheim, laid out in 1762 by German ironmaster Henry William Stiegel and located about eleven miles north of Lancaster Borough.5 |

|

| ||

Left: Armchair with pierced back, probably Lancaster County, Pa., ca. 1760–75. Walnut. H. 43⅝, W. 24¼, D. 19¼ in. An example of the vernacular Pennsylvania furniture John referred to as “weird but wonderful,” this highly unusual armchair — from the pierced splat to the scalloped crest and serpentine arm supports — is a Germanic interpretation of cabriole leg seating furniture.

Right: Tall clock (and detail), case attributed to workshop of Emanuel Deyer (1760–1836), movement signed by Jacob Eby (1776–1828), Manheim, Lancaster County, Pa., ca. 1810. Mahogany veneer and mixed-wood inlay, tulip poplar. H. 98, W. 20¼, D. 10 in. John Snyder collected numerous examples of furniture from the Manheim workshop of Emanuel Deyer and his sons George, John, and Samuel. The Deyers are known to have made case furniture as well as architectural woodwork, including for the Old Zion Reformed Church near Brickerville, Lancaster County. Several dozen clock cases with distinctive eagle inlays associated with the Deyer shop are known, most in walnut or cherry cases. This veneered mahogany, bow-front example is one of the most sophisticated clock cases produced by the Deyer shop. American bow-front clocks are quite rare; most known examples were made by the Deyers.6 Most Deyer clock cases have movements made by Jacob Eby, a Mennonite clockmaker in Manheim. Snyder acquired this clock at a local auction in 2009. |

|

|

Tall chest of drawers, attributed to workshop of Emanuel Deyer (1760–1836), Manheim, Lancaster County, Pa., ca. 1810. Walnut, holly, white pine, brass. H. 65¼, W. 47½, D. 26¼ in. This bow-front tall chest of drawers is also from the Deyer workshop. The upper two drawers of this chest are actually doors that open vertically in the middle to reveal a sizable compartment. John took great delight in telling visitors to open one of the upper drawers and watching their astonishment when the concealed cupboard was revealed instead. |

|

|

Creamer and chatelaine, made by Peter Getz (1764–1809), Lancaster Borough, Lancaster County, Pa., ca. 1790–1800. Silver. H. 5¾, Diam. 2⅜, D. 4⅛ (creamer); L. 19⅛, W. 1¼, D. ⅝ in. (chatelaine). Lancaster was home to numerous silversmiths, foremost among them Peter Getz. Other Lancaster silversmiths represented in the Snyder collection include David and Charles Hall, William Haverstick, and Lewis Heck. Like many silversmiths, Getz supplemented his income with other work including engraving and repairs, as well as selling ready-made items ranging from silver spoons and mourning rings to buttons and artificial teeth. |

|

|  | |||

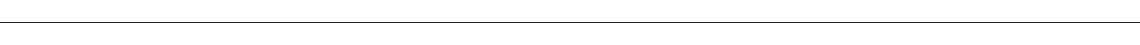

Left: Portrait of Jacob Frey (1744–1829), attributed to Jacob Eichholtz (1776–1842), Lancaster County, Pa., 1815.

Jacob Frey worked variously as a tailor, shopkeeper, and tavern keeper in Lancaster Borough. He also became a land speculator and by 1814 was among the wealthiest 10 percent of the town’s residents. It was during that time that Frey and his wife, Catharine, had their portraits painted by Lancaster’s preeminent artist, Jacob Eichholtz; by the end of the decade, the real estate market had collapsed and the Freys lost their fortune. Right: Portrait of Henry Bates Grubb (1774–1823), attributed to Thomas Sully (1783–1872), Philadelphia, Pa., ca. 1825.

A third-generation member of one of Pennsylvania’s foremost families of ironmasters, Henry Bates Grubb and his older brother inherited the family business at ages eleven and thirteen, when their father Peter Grubb Jr. committed suicide in 1786. Following a contentious estate settlement, Henry bought out his brother’s share and rebuilt the family business. His iron holdings grew to become one of the largest in Pennsylvania, the centerpiece of which was the Mount Hope Furnace in northern Lancaster County. In 1800, Henry embarked on the construction of a large mansion at the Mount Hope property, to which he added elaborate formal gardens and even an Episcopal chapel, where Henry was buried following his death in 1823 at the age of forty-nine. This portrait may have been painted posthumously; Sully is known to have painted Grubb’s widow, Harriet Amelia Buckley of Philadelphia, in 1824–25. The profile format is unusual in Sully’s work and may indicate it was copied from an earlier portrait by a different artist. | ||||

|

|

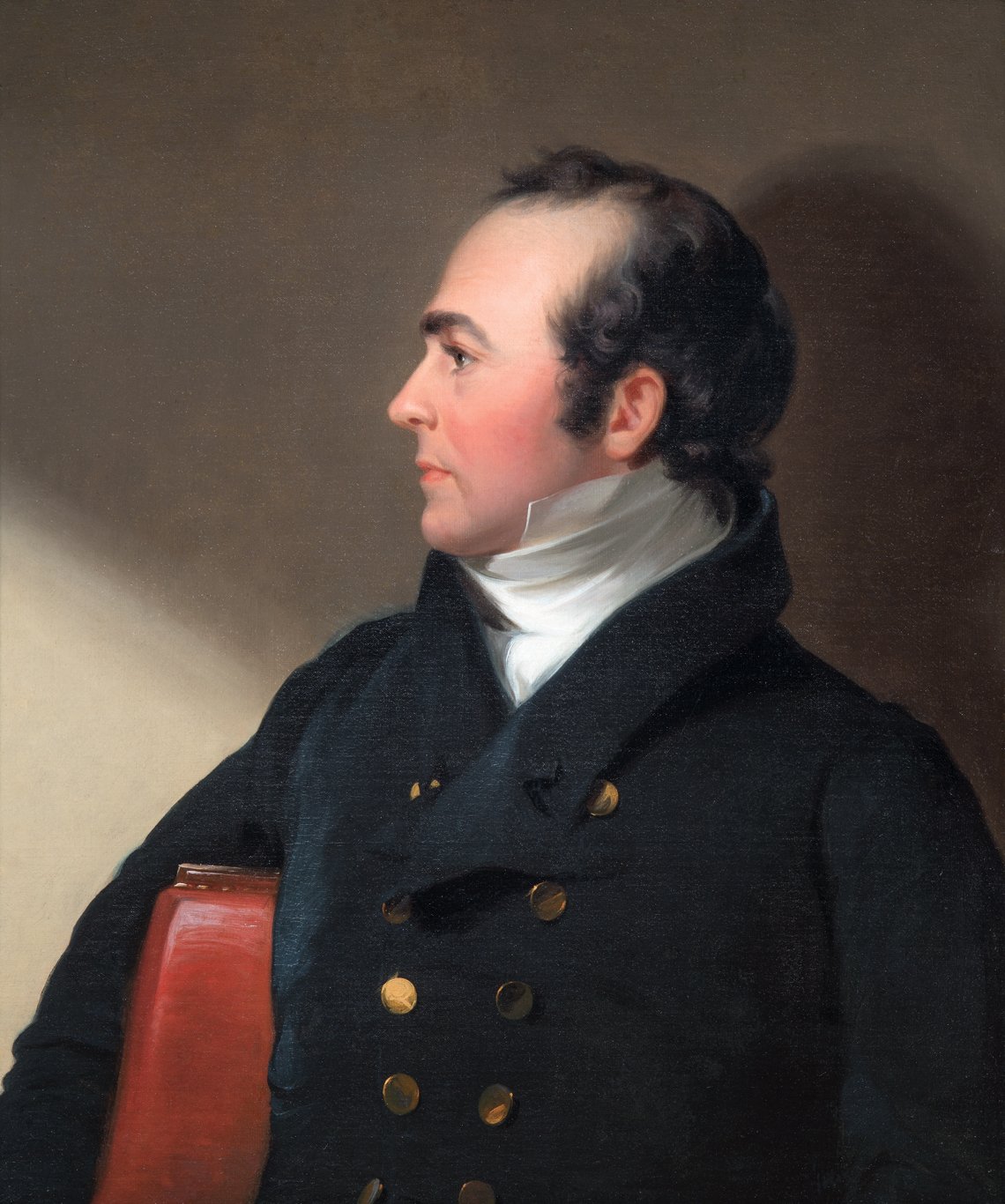

View of the Susquehanna River, signed by J.P. Beck (n.d.), probably Lancaster County, Pa., ca. 1825–50. Oil on canvas, 12½ x 25½ inches. Now hanging in the front parlor of Rock Ford, this Susquehanna River scene was one of John’s favorite paintings. Its dreamy landscape conjures up a timeless image of central Pennsylvania’s main waterway, one that John knew well from the windows of his beloved Toad Hall. Unlike the insufferably vain Mr. Toad of The Wind in the Willows, however, John Snyder was just the opposite—kind, caring, and selfless to the very end. The gift of his vast, lifelong collection of Lancaster County decorative arts to Rock Ford Plantation is an inspiration to us all. |

|

Lisa Minardi is the executive director of The Speaker’s House in Trappe, Pa., and a specialist in Pennsylvania German art and culture.

|

1. John J. Snyder Jr. “The Bachman Attributions: A Reconsideration.” In The Magazine Antiques 105, no. 5 (May 1974): 1056–65; also John J. Snyder Jr., “Carved Chippendale Case Furniture from Lancaster, Pennsylvania.” In The Magazine Antiques 107, no. 5 (May 1975): 964–75.

|

2. Stacy B. C. Wood, Jr., Stephen E. Kramer, III, and John J. Snyder Jr. Clockmakers of Lancaster County and Their Clocks, 1750–1850 (New York: Van Nostrand Reinhold, 1977). John J. Snyder Jr., “Clock Cases,” in Richard S. and Rosemarie B. Machmer, Berks County Tall-Case Clocks, 1750–1850 (Reading, Pa.: Historical Society Press of Berks County, 1995), 13–31.

|

3. For an image of the schrank, see Jack L. Lindsey, Worldly Goods: The Arts of Early Pennsylvania, 1680–1758 (Philadelphia: Philadelphia Museum of Art, 1999), 8.

|

4. For more on this group, see Lisa Minardi, “Sulfur Inlay in Pennsylvania German Furniture: New Discoveries,” in American Furniture, ed. Luke Beckerdite (Hanover, NH: University Press of New England for the Chipstone Foundation, 2015), pp. 98–125.

|

5. For related examples of Manheim carving, see Wendy A. Cooper and Lisa Minardi, Paint, Pattern & People: Furniture of Southeastern Pennsylvania, 1725–1850 (Winterthur, Del.: The Henry Francis du Pont Winterthur Museum, 2011), 106–7.

|

6. At least five bow-front clock cases from the Deyer shop are known, including one at Winterthur Museum; see Paint, Pattern & People, 184.