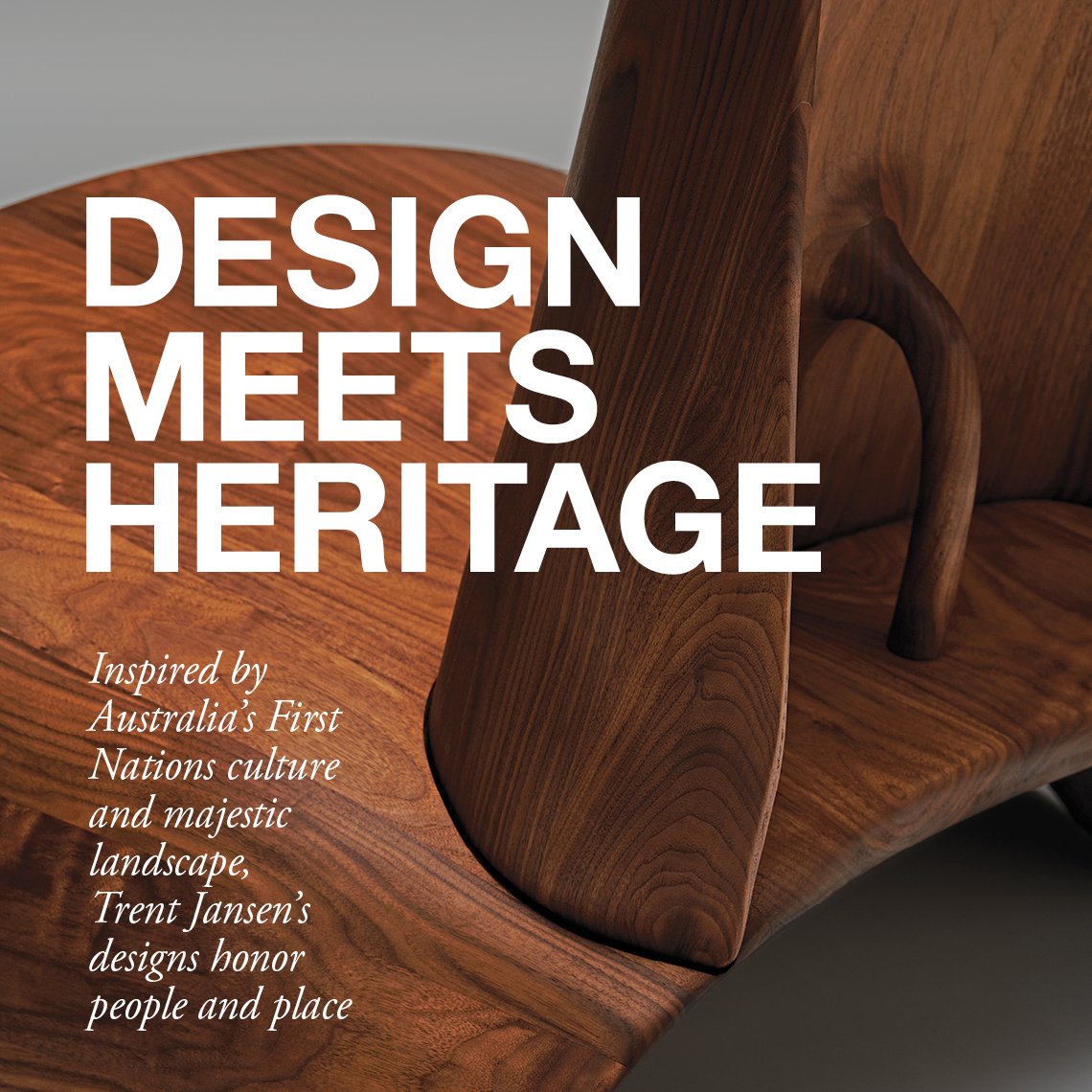

Design Meets Heritage

Inspired by Australia’s First Nations culture and majestic landscape, Trent Jansen’s designs honor people and place

|

Photo: © Fiona Susanto |

by Benjamin Genocchio

Australian designer Trent Jansen likes to show his work at museums and galleries internationally for global exposure and to connect with a wider audience outside the Australian continent. Lately, he has been participating in design fairs and in December 2024, with help from cultural grants from the Australian government, the 42-year-old designer and two Australian Indigenous designer colleagues collaborated on a booth for Design Miami.

“Australia has little appetite for collectible design — there are maybe 10 or 15 people who might consider buying this kind of design. We decided it was critical to promote our work overseas.” The budget was so tight the three of them shared an Airbnb and cooked their meals each night to save money. “Overruns on shipping costs,” Jansen explains. Their gamble paid off because veteran design dealers Lewis and Sherri Wexler from Wexler Gallery in Philadelphia and the New York Design Center stopped by the booth to talk to Jansen. They returned the following day for a further chat, and the next day, and by the end of the fair they asked to represent Jansen, becoming his first gallery representation in the United States.

|

Top left: The Manta Pilti/Dry Sand Cabinet designed by Trent Jansen with Indigenous designer Tanya Singer. The design of the cabinet, with its fissurelike opening and sculptural facets, was inspired by an image of the cracked, parched earth in Central Australia, the effect of climate change on an already hot, dry climate. Top right: The sculptural profile of the Manta Pilti/Dry Sand Cabinet. Each facet is meticulously hand-sanded and hand-assembled, representing hundreds of hours of work. Bottom left: Aboriginal master carver Errol Evans, Indigenous designer Tanya Singer, and designer Trent Jansen collaborated on the design and crafting of the Manta Pilti cabinet. Bottom right: The Manta Pilti/Dry Sand Low Chair, shown in American hard maple and oiled American walnut, also available in cherry. A standard height version of the chair is also available. All photos © Fiona Susanto |

“When we saw Trent Jansen’s work at Design Miami we were completely enchanted,” says Lewis Wexler. “The work is beautifully designed and crafted at the highest skill level. But what really intrigued us was the concept behind the work. Trent is an exquisite designer, but his use of historical references and the environment of the Australian outback as direct influences really sets him apart from many designers we have encountered. Coupling those influences with the use of Aboriginal craftspeople aiding in the creation of the work makes for a powerful combination. We feel strongly that anyone who encounters Trent’s work will be as drawn to the pieces as we are. It is an honor to be representing him and those who work with him.”

“I really liked Lewis and Sherri — they are just wonderful people,” the designer says about the encounter in Miami. “For me, the relationship is paramount and they just ‘got’ the work right away — most people who encounter my objects want to know what the work is made of and the price. Lewis and Sherri were keen to hear what the work is about, what drives me. They took time to ask about my background and interests and what inspires me. We got along well.”

|

As a beloved symbol of Indigenous cultural identity and a poignant reminder of the impact of climate change, the Manta Pilti/Dry Sand Cabinet and Credenza include a life-size cast bronze sculpture of the Parakeelya flower. A succulent plant important to survival in the desert, it once covered the hills of Central Australia and is now increasingly rare. Photos: left © Tanya Singer, right © Fiona Susanto |

|

The Manta Pilti/Dry Sand Credenza in American walnut, designed by Trent Jansen in collaboration with Tanya Singer. Edition of 3 + 2 AP, 2023. Also available in American hard maple and American cherry. The impact of climate change resulting in brushfire depletion of Australia’s forests makes sustainably harvested American hardwoods, surprisingly, the most ecologically responsible choice of material. Photo © Fiona Susanto |

Jansen describes himself as a design anthropologist. It is an apt description for this thoughtful, idiosyncratic designer of limited edition and one-of-a-kind conceptual furniture. His work takes inspiration from topical social and cultural issues in his native Australia, where he maintains a home and studio on the New South Wales southern coast, a few hours outside of Sydney. “I was trained as a conceptual designer at a design school teaching the Dutch Conceptual Movement of the 1990s, so my sensibility combines European conceptual design with an ecological focus,” he says.

Every object Jansen makes tells a story. His narratives range from environmental change and the possibilities of material recycling to the displacement and marginalization of Australia’s Aboriginal population. His first design object, made in 2004, was the “Sign Stool,” a stool made from reclaimed Australian road signs in homage to well-known Australian artist Rosalie Gascoigne, who is known for her use of found objects in her work. He credits his interest in ecology, recycling, and storytelling to his schooling — he completed a PhD in Design — and also to his time working in Amsterdam with internationally acclaimed Dutch designer Marcel Wanders, who instilled in him the importance of an intellectual foundation for objects.

|

The scaly covering of the Pankalangu, a mythical creature from Aboriginal legend, inspired the Pankalangu Cabinet (top right) and Credenza (bottom, and detail, top right). “Scales” of deep, rich Queensland walnut tipped in gleaming copper create a dramatic chiaroscuro effect. Each a limited edition of 3 + 2 AP. All photos © Michael Corridore |

“Trent Jansen has a great deal of respect for cultural heritage and is extraordinarily thorough in incorporating cultural identity and history into his works,” Wanders remarked about the designer. Working together with Wanders in his studio also taught him the power and importance of collaboration in the contemporary design process. Today Jansen works extensively with other designers and makers, especially Aboriginal Australians often marginalized in the design community.

Three of Jansen’s objects are on display at Wexler Gallery in the New York Design Center. Among them is his prized “Manta Pilti | Dry Sand Cabinet,” completed in 2023 after years of collaboration with indigenous designer Tanya Singer, who comes from the Indulkana Aboriginal community. The story of this cabinet is the impact of climate change on remote Central Australia. It is getting hotter and drier in Indulkana, a place that was already hot and dry, and the ground has recently started to harden and crack apart in places. Singer and Jansen took imagery of the cracked, parched earth around Indulkana as inspiration for the cabinet. The Manta Pilti is a phrase that means “dry sand” in the Central Australian Aboriginal Pitjantjatjara language. “The process of collaborating cross-culturally, halfway across the country, was not easy for any of us,” Jansen says, “and that is why it took so long for us to bring this design to fruition. But I loved going to Indulkana, learning about their language, culture, and community.”

The “Manta Pilti | Dry Sand Cabinet” is from an edition of 3. This edition is made of American hard maple wood, a natural sustainably harvested resource. “We research the woods we use thoroughly to be sure that they are sustainably managed,” he explains. “We always use local hardwoods where we can but environmentally this isn’t always the best option. Due to bushfire depletion of Australian forests, some imported woods turn out to be more sustainably managed resources than what we can obtain here. Furthermore, the carbon footprint of shipping is low compared to the impact that the Australian forestry industry has on the natural landscape.”

|

Elite interior design firm Dunnam Zerbini Design chose the extraordinary Pankalangu Credenza for the 30-foot-long entry gallery of a Central Park home. Above the Credenza, a dynamic work by Mark Grotjahn from his Backcountry series, with a custom hand-blown Continuum Chandelier by Avram Rusu Studio. Photo by Nick Johnson, courtesy Dunnam Zerbini Design |

The cabinet includes a life-size cast bronze flower resting on one of the inside shelves. It is a realistic depiction of the Parakeelya flower, a succulent that grows in Central Australia and is well known among the Aboriginal people because it retains and yields moisture, making it important for survival in the desert. At one time the hills were covered in this purple flower but because of the changing climate, it is becoming rare. “The Parakeelya flower was such an important part of the ecosystem in the desert for humans and animals, and its disappearance is one of the most tangible signifiers of the impact of climate change,” Jansen says.

Jansen takes pride that all of his design objects are complicated and labor-intensive to produce. “Sometimes the technology or the process doesn’t exist to make what we are looking for and so we have to invent it,” he says. The “Manta Pilti | Dry Sand Cabinet” design was first modeled on a computer, a process that took Jansen more than nine months. Maker Chris Nicholson then formed the raw surfaces using a combination of hand lamination bending and five-axis CNC machining, hand-finishing the pieces with hundreds of hours of sanding. The cabinet is then hand-assembled, with each of the curved, faceted surfaces glued together with wood and then layered on an engineered substrate that is physically stable.

The Pankalangu Credenza and Cabinet are part of a stunning design series inspired by the ancestral folklore of the Western Arrernte Aboriginal people. The Pankalangu is a “territorial being that lives in the scrub and is completely camouflaged in the desert and bush,” Jansen explains. To evoke the image of this magical, mythical creature, Jansen adorned his cabinet and credenza with hundreds of scales made from Queensland walnut and copper, materials that variously absorb and reflect ambient light, creating shimmering, glistening silhouettes. Esteemed New York interior design firm Dunnam Zerbini recently placed a Pankalangu credenza in the gallery hall of a spectacular art and design-filled Central Park project. Trent Jansen’s work more than holds its own alongside top-tier collectible design by Michael Coffey and Mattia Bonetti, and artworks by Damien Hirst, Julian Schnabel and Mark Grotjahn.

“Trent's furniture objects are handmade works of art,” says William Smart of Smart Design Studio in Sydney, a frequent purchaser of Jansen’s work for his interior design projects. “We often use them as the centerpiece of a room as they have a commanding presence and are 'next level' in terms of craft and individuality. Our clients always want to know the story behind these pieces; their forms and textures invite conversation. Hearing Trent explain the research, the concept and the makers behind each piece makes them even better,” he says.

| |

| |

For the series Ngumu Janka Warnti (All Made from Rubbish), Trent Jansen collaborated with Indigenous saddler Johnny Nargoodah, working with aluminum mesh found at scrap yards. In an experimental “design by making” process, hand hammering the mesh and working with pliers resulted in biomorphic, sculptural furniture forms laminated with New Zealand saddle leather, a process the partners invented. The series includes a bench, a cabinet, low back and high back chairs, and a vessel. Top: Trent Jansen and Johnny Nargoodah, photo © Romella Pereira Bottom: Johnny Nargoodah turning scrap into the sublime. Photo courtesy Trent Jansen Studio |

Smart believes Jansen’s designs are special because of a commitment not only to great design and to craftsmanship but also to the people he collaborates with. Gamilaraay and Dharug designer Bernadette Hardy has worked frequently with Jansen and agrees with this assessment. “More than just collaboration, Jansen builds lasting relationships that extend beyond the final product, ensuring that the voices and stories of those he works with continue to shape narratives of culture and identity,” she says. “These partnerships have produced objects that honor marginal histories and cultural narratives, telling relational stories that offer a new foundation for Australian identity.”

Jansen’s chairs are also on display at the Wexler Gallery in New York, each made with a different focus and collaborator. One is a simple, hand-carved wooden chair with a powerful visual impact, titled “Kutitji Chair,” the Pitjantjatjara word for a “shield.” Its design is derived from traditional Aboriginal shields found in the northern area of Australia where there is a plentiful wood supply. “That’s a collaboration with Errol Evans, an Aboriginal carver from far North Queensland,” Jansen explains. “He is a maker of traditional artifacts and a master at turning wood.”

“When I first met Trent I was skeptical about the project he proposed and how it would work,” says Evans, a Djabugay and Western Yalanji designer. “But after a week of searching online for meaningful collaborative design ideas, we sat down and shared about ourselves. We took Trent out “on Country” and talked about climate change and how it's affecting everyone all over the world. This project is something very special to us as we had the chance to show our stories through our designs.”

|

The waffle-like pattern of the aluminum mesh frame ebbs and flows with the contours of the form, tight and consistent in some areas, stretched and irregular in others. As handmade objects, each is unique, and these works are simultaneously conceptual and functional. Clockwise from top: Ngumu Janka Warnti (All Made from Rubbish) Bench in black; Low Chairs in black and brown, High Back Chair in brown. Top photo © Jeremy Park, all others © Romella Pereira |

A second chair shown at Wexler is part of an ongoing series titled Ngumu Janka Warnti (All Made from Rubbish), with works made from discarded materials. “The substrate is aluminum mesh, recycled, available as scrap metal,” the designer explains. “This series is a collaboration with Johnny Nargoodah, a saddler who has worked on remote cattle stations. We went together to a scrap yard, found what we could, and experimented. It is made of hand-hammered mesh laminated with leather, a process we invented. Three cow hides are used to make each chair. We have now made a cabinet, a bench, chairs, and tables from this material and have experimented with different colors for clients.”

|  | |

Designed by Trent Jansen in collaboration with Aboriginal carver Errol Evans, the Kutitji Chair’s design was based on traditional Aboriginal shields. (Kutitji is a Western Desert Language dialect word for shield.) The project began with an exchange of sketches of traditional shields and weapons as components of a chair, and evolved into this elegant, hand-carved, coopered form. The handle on the back mimics handles on the back of Aboriginal shields traditionally used for hunting and defense, and reinforces the structure. Here, the shield is both form and symbol, as the artists call attention to climate change — whose effects are particularly harsh on the Indigenous population — referencing the earth’s ozone layer as a precious protective shield. Photos © Fiona Susanto | ||

Lewis Wexler says that the response to Jansen’s works at the Wexler Gallery has been overwhelmingly positive. “The “Manta Pilti” cabinet is like a magnet that draws clients in. There is a sense of delight and wonder when people get close to it and witness the impeccable craftsmanship. Everyone wants to open it! His Nguni Janka Waranti series attracts both designers and makers. His work is so different from the “norm” because it is steeped in Australian culture and design sensibility. Viewing Trent’s work is a unique experience. People are just amazed and that amazement is what drew me to his work in the first place.”

In May 2024, Jansen opened a 20-year survey of his work at Melbourne Design Week. “I can't believe it's been 20 years. I feel like I am only getting started,” he says. Jansen continues to work on designs every day in his studio, where he works alone or sometimes with the help of one assistant. “I am open to anything, and the less orthodox the better,” he says, laughing. I experiment, and love different processes and materials, mixing cultures and areas of craft and expertise. This way of working can inspire something unique and new, taking us out of our comfort zones.”

|

Discover More Designs From Trent Jansen

at Wexler Gallery on Incollect

|