Art of the People: Folk and Outsider Art in Vermont

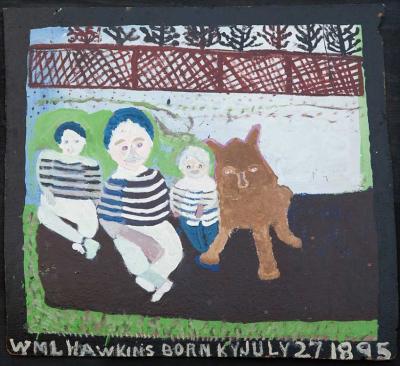

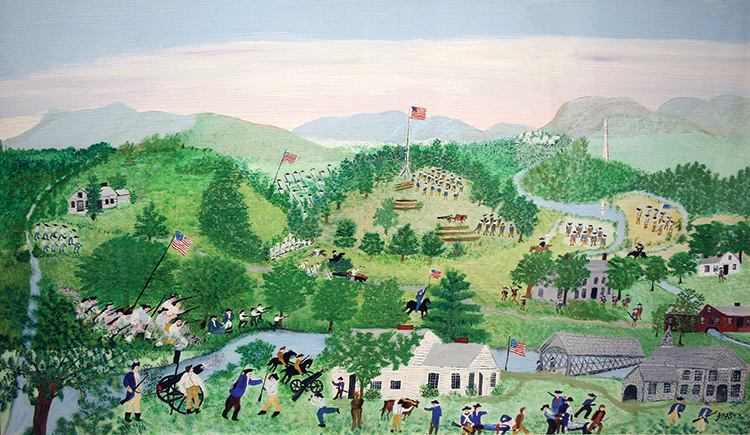

- Fig. 1: Anna Mary Robertson “Grandma” Moses (1860–1961)

Battle of Bennington, 1953

Oil on pressed wood, 18 x 30 inches

Bennington Museum Collection, Gift of Carol and Arnold Haynes (2014.40)

© 2014 Grandma Moses Properties Co., New York

Moses lived and worked for most of her life just across the Vermont border

in New York State.

The Bennington Museum of Vermont is noted for its collection of paintings by Anna Mary Robertson “Grandma” Moses (Fig. 1), seen by many as the quintessential example of an American artistic autodidact. Seeking to provide a broader context for understanding Moses’ creative output, the museum recently began to actively collect the work of modern and contemporary self-taught artists with ties to the region, including Gayleen Aiken (Fig. 2), Larry Bissonnette, Paul Humphrey, Ray Materson, and Jessica Park.

Acknowledging the rapidly increasing significance accorded to work by self-taught artists in America’s art historical narrative, Bennington Museum has brought together an eclectic selection of approximately 150 objects that draw on the museum’s historic folk art and on a private collection gathered together by Gregg Blasdel and Jennifer Koch during the last fifty years. The exhibition, “Inward Adorings of the Mind”: Grassroots Art from the Bennington Museum and Blasdel/Koch Collections, highlights thematic dialogues among extraordinary artworks created by everyday people from the eighteenth century to the present, with material ranging from textiles, ceramics, and weathervanes to drawings, paintings, and sculpture.

No single term captures the vital, shape-shifting nature of the art in this exhibition. The non-hierarchical, bottom-up connotations of “grassroots,” however, seems as apt today as it did nearly fifty years ago when Gregg Blasdel introduced the term in an article he wrote for Art in America.1 Blasdel played a pivotal role in bringing the creations of idiosyncratic, self-taught artists to public attention during the 1960s when, as a budding artist, he began documenting the work of grassroots artists. In the 1990s, Jennifer Koch, also an artist, joined Blasdel in seeking out objects that challenge our understanding of art and creativity. Their collection reflects a growing awareness that the work of these untrained makers is integral to the story of American art.

Grassroots Art is organized thematically to emphasize underlying continuities among the work of diverse, often anonymous, self-taught artists across centuries and cultural backgrounds. The four thematic sections in the exhibition are: History, Memory and Memorials; Signs and Symbols/Words and Images; Faces: Fact and Fiction; and Everyday Beauty: Whimsy and Utility. There is much overlap among these categories. Drawings by Gayleen Aiken (fig. 2), for example, are included in multiple sections, while many other objects straddle them.

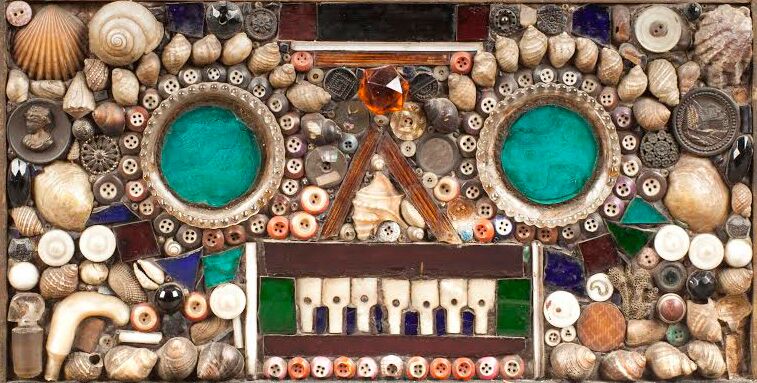

- Fig. 3: Stephen C. Warren (1824–1905)

Memory Ware Tower, 1894

Found objects (including glass, shells, buttons, jewelry, and two tintype photographs) embedded in putty, paint, and metal on wood, 45 x 16½ x 16½ inches

Bennington Museum Collection, Museum purchase with support from Mark Barry and Sandra Magsamen, Marc and Fronia W. Simpson (2015.19)

History, Memory and Memorials

Key ingredients in the work of many grassroots artists from the eighteenth century through the present day are interests in public history, personal memories, and a penchant for commemoration. One of the greatest distinguishing characteristics of these works is the fluidity with which they move among the realms of public and private, real and imagined. Many of these works project an aura of fact-based authenticity. Nevertheless, all are tinged, or in some cases dominated, by a dream-like quality of half-remembered people, places, or things.

Designed to look like a scale model of an observation tower, with a complex spiral staircase and umbrella-covered observation deck, from which the maker can metaphorically survey his own life, the surface of this Memory Ware Tower (Fig. 3) by Stephen C. Warren, whose occupation was recorded as “Jack-at-all-Trades” on his Civil War enlistment papers, is covered with an artful arrangement of glass, shells, buttons, jewelry, and even two gem-size tintype photographs. Although the inspiration for this work is unknown, many of these trinkets presumably had strong personal associations for the artist.

Anna Mary Robertson “Grandma” Moses set the standard for so-called “memory painters,” with her animated paintings of life in rural America. Her sophisticated meldings of fact-based history and associative memory rise far above sentimental nostalgia. The Battle of Bennington (see fig. 1) depicts a historic event filtered through the artist’s unique visual style and deeply rooted personal associations. Fought only a few miles from where the artist lived most of her life, the Revolutionary War battle was an event of significant local lore. Not one to be shackled by historical accuracy, Moses relied as much on her artistic sensibility as on known facts. When asked in an interview why she had included the Bennington Battle monument in the painting (upper right) despite the fact that it wasn’t built for more than a century after the battle, Moses replied, “Well, I put the monument in because it looked good, I guess.”

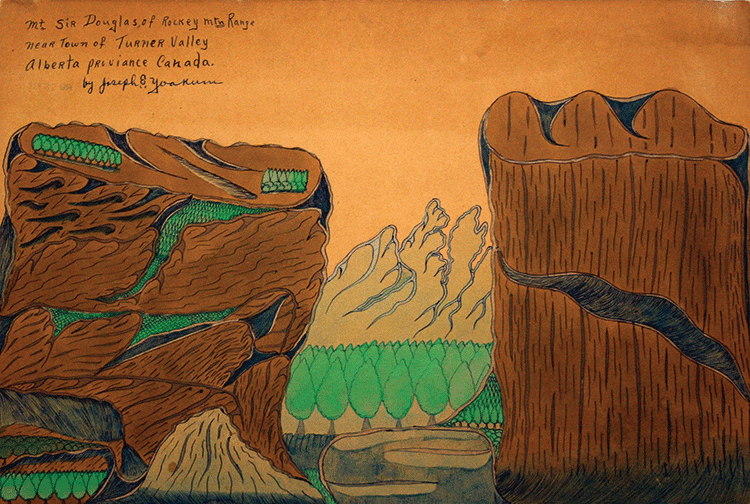

Joseph Yoakum was a different type of “memory” artist, creating a remarkable body of drawings depicting sites he may or may not have actually visited as a younger man. His biography is sketchy and undoubtedly slanted by his own penchant for self-mythologizing, but he claimed to have visited all the geographic locales represented in his more than two thousand drawings. Whether or not he actually experienced these sites in person is less important than the extraordinary formal inventiveness with which he depicted them on paper (Fig. 4). Yoakum’s drawings are utterly distinctive, with their writhing line, disjointed space, and interlocking forms, all brought together by his sensitive color sensibility.

Signs and Symbols/Words and Images

In their ardent desire to communicate with the world around them, whether for practical or personal reasons, grassroots artists often put an especial emphasis on bold, graphically powerful imagery and frequently combine their images with text to reinforce their intended message. Ranging from a trade sign used by one of Bennington’s first doctors to Jesse Howard’s signs extolling his idiosyncratic personal views on politics and religion (Fig. 5), or the romantic, image and text-laden textile samplers of the nineteenth century to the comic-like combination of images and words in Gayleen Aiken’s manic, incantatory drawings (fig. 2) based loosely on her memories growing up in Barre, Vermont, grassroots artists have been combining symbols and words to bring home their point for centuries.

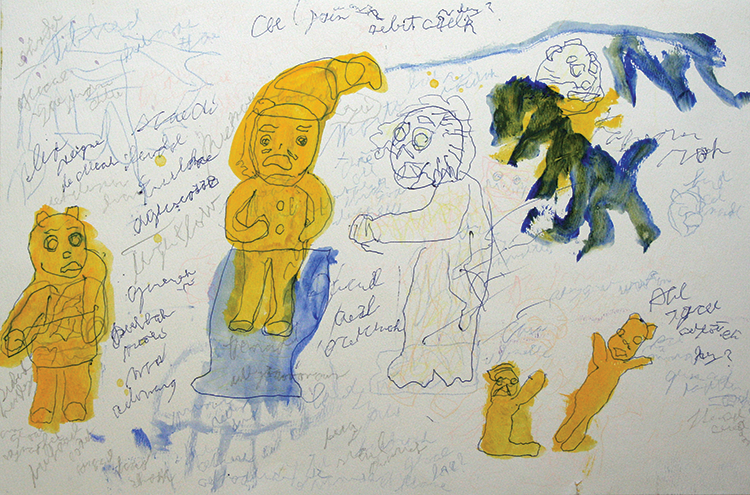

The words and images grassroots artists use do not always cohere into a readily comprehensible message for the viewer, despite the artist’s readily apparent, even urgent, desire to communicate. Robert Gove, who participated in artmaking sessions organized by GRACE, or Grassroots Art and Community Effort, a progressive workshop founded in 1975 by Don Sunseri in Vermont’s Northeast Kingdom, created lively, cryptic drawings filled with anthropomorphic bears and intensely scribbled texts (Fig. 6). Though the artist’s intent behind these works is unclear, the seemingly indecipherable manifestos underline the intense human need to express one’s self and connect with others, a fact made all the more poignant by their mystery to anyone other than the artist.

Faces: Fact and Fiction

Portraits, such as those created by the itinerant artists who plied their trade in New England throughout the first half of the nineteenth century, tend to be thought of as documentary evidence, objective visual facts that provide insight into our past. And this is exactly why they were collected in large numbers by the Bennington Museum during the early- to mid-twentieth century. However, when “traditional” folk portraits by Justus Dalee, Erastus Salisbury Field, Ammi Phillips, and numerous other unidentified itinerant artists (Fig. 7) are paired with images of invented characters by contemporary self-taught artists, such as those by Paul Humphrey (Fig. 8), Gayleen Aiken (fig. 2), or Inez Nathaniel Walker, the constructed, highly wrought nature of portraiture becomes glaringly apparent. Portraits of real people depend more than we might imagine on artificial constructs, such as a highly conscious selection of clothes or accessories, to convey “meaning” or a sense of their sitters’ personalities and social standing. Invented portraits often obscure their underlying psychological power with these same tropes, to depict seemingly real people, who, in fact, only exist in the artists’ minds.

During the last twelve years of his life, Paul Humphrey, a life-long Vermont resident, created hundreds of images, with multiple iterations of each, that he referred to as his “sleeping beauties” (fig. 8). Humphrey claimed that his first such image was based on a photograph of his daughter, Sandra Sue. However, after the artist’s death it was discovered that the personal narrative he shared with friends was largely fiction.2 In fact, he had no daughter, and the source of his images was primarily magazines, which Humphrey photocopied and then aggressively re-imagined, using correction fluid to shut the eyes of his subjects and otherwise alter their features. He used ash to create shading, sometimes filtered through a wire mesh, and additionally amended the images with drawing. These altered images were used as templates, which Humphrey re-photocopied, adding color with colored pencils, watercolor, and/or markers to create the end product.

Everyday Beauty: Whimsy and Utility

Utilitarian objects, found or discarded materials, and artists’ seemingly mundane experiences form the foundation of a large percentage of grassroots art. Taking elements from their everyday lives, grassroots artists make objects of beauty and intrigue, often displaying a baroque love of elaboration, or reveling in whimsy and fantasy for its own sake. The seeming dichotomy between utility and whimsy and their attendant tension is at the heart of traditional as much as contemporary folk art.

This section brings together a wide-ranging selection of utilitarian objects, such as furniture, pottery, and textiles, with more whimsical, purely decorative or fantastic images and constructions, such as floral paintings and bottle whimsies (like traditional “ships-in-a-bottle” with a twist) to draw out these tensions and question just how far apart function and fantasy really are—or are not.

The paint decoration seen on the chest in figure 9 and the other pieces associated with the Matteson family of South Shaftsbury, Vermont, imitates the more expensive veneers of figured cherry, maple, and mahogany frequently used to dramatic effect by other Vermont cabinetmakers during the early nineteenth century. Yet, like many other examples of faux-painted American furniture from this period, the decorator has taken liberties and produced a graphically appealing, almost abstract surface of swirling paint that enlivens the chest’s surface and any room in which it stands.

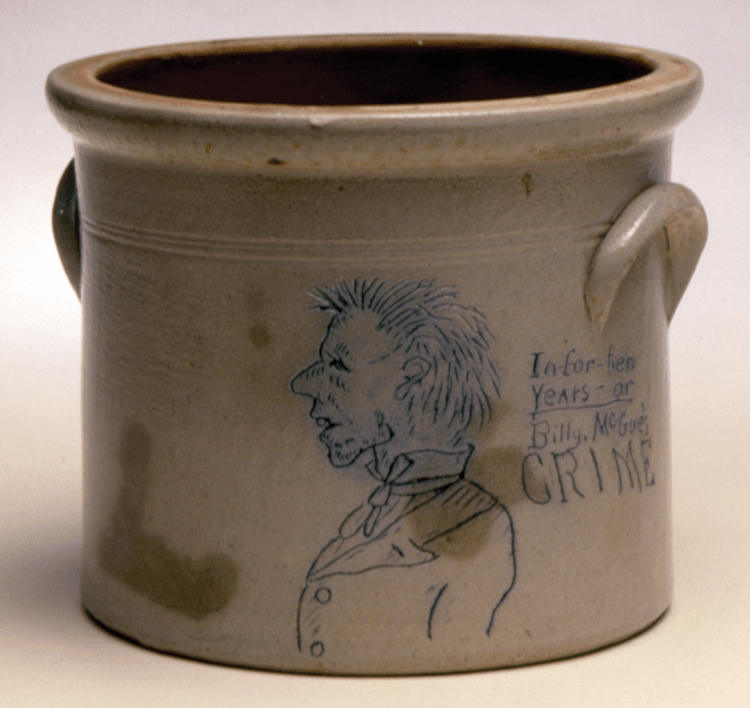

Known for their well-made, artfully decorated wares, Bennington’s Norton family became one of New England’s pottery dynasties during the nineteenth century. Most Norton pots were embellished with bold, beautifully brushed cobalt designs of flora and fauna. On rare occasions they made pots that told a story. This small, straight-sided pot has a typical brushed leaf design on the front side. However, on the back of the pot, an evocative portrait of a tousled, unshaven young man is incised, with the caption: “In for – ten / years – or / Billy. McGue’s / CRIME” (Fig. 10). The pot may depict William J. McCune who had many run-ins with the law in Bennington and elsewhere during the 1870s.3

Face jugs are one of the most iconic forms of vernacular pottery made in the American Southeast. Believed to have originated with slave potters in South Carolina’s Edgefield District immediately prior to the Civil War, they were revived during the mid-twentieth century and continue to be made in large numbers to this day. Face jugs made during the last fifty years form the largest and most significant sub-collection within the larger Blasdel/Koch Collection (Fig. 11). There are many theories regarding the meaning behind the inclusion of grotesque faces on these jugs, but the inclusion of horns on this “devil jug” by Terry Allman suggests a warning against the presumably alcoholic contents contained within.

Ray Materson began making his exquisite, finely detailed miniature embroideries from unraveled sock thread while he was serving a fifteen-year prison term for drug-related offenses; the pieces typically measure no larger than 3 x 2½ inches and take between forty and sixty hours to create (Fig. 12). More recently, Materson has been a vocal advocate for substance abuse education and, in 2003, he was the first artist to receive the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation’s Innovators Combating Substance Abuse Award. From 2009 to 2011 he lived in Vermont, making a living as a social worker, and witnessed the state’s opiate addiction crisis first hand. Using everyday materials and drawing on his own personal experiences, Materson’s jewel-like embroideries bring the long tradition of American needle arts into the twenty-first century.

“Inward Adorings of the Mind”: Grassroots Art from the Bennington Museum and Blasdel/Koch Collections is on view at the Bennington Museum, Bennington, Vermont, through November 1, 2015. For information visit www.benningtonmuseum.org or call 802.447.1571.

Jamie Franklin is curator at the Bennington Museum, Bennington, Vermont.

This article was originally published in the Autumn 2015 issue of Antiques & Fine Art magazine, a digitized version of which is available on afamag.com. Antiques & Fine Art and AFAmag are affiliated with InCollect.com.

2. Gregg Blasdel, “Paul Humphrey: Art is all I have,” Raw Vision, 35 (Summer 2001): 60–65.

3. Cathy Zusy, Norton Stoneware and American Redware: The Bennington Museum Collection (Bennington, VT: Bennington Museum, 1991): 47.