Artistic Furniture of the Gilded Age: Herter Brothers and the William H. Vanderbilt House

This archive article was originally published in the 16th Anniversary issue of Antiques & Fine Art magazine.

William H. Vanderbilt (1821–1885), the son of Cornelius “Commodore” Vanderbilt (1794–1877), inherited a vast fortune and a lucrative transport business that he expanded exponentially to become one of the wealthiest men in America. In 1879 he built an enormous mansion to mark his elevated social and economic status. It spanned a city block on Fifth Avenue, between 51st and 52nd Streets (Fig. 1). Vanderbilt commissioned Christian Herter, at the time the principal of Herter Brothers, one of the premiere cabinet-making firms in New York, to decorate and furnish his home. It took between six hundred and seven hundred men to construct and decorate the house, and was completed in a remarkable two years.

Herter Brothers, founded in the mid-1850s by German émigrés Gustav and Christian Herter, catered to a clientele that epitomized the country’s post-Civil War prosperity. The Vanderbilt commission, the crowning achievement of Herter Brothers’ illustrious career, provided the firm with the opportunity to create a sumptuous cosmopolitan environment under few financial constraints. Herter Brothers devised distinct decorative schemes for each room of the mansion, drawing inspiration from a wide range of historical styles, and executing their designs in luxurious and exotic materials. Vanderbilt closely followed the construction of his house and visited the Herter Brothers workshops almost daily. Moreover, he had the house exhaustively chronicled with descriptions, line drawings, and rare color lithographs, and commissioned contemporary art critic Earl Shinn, under the pseudonym of Edward Strahan, to write and produce a magnificent limited edition four-volume album. This comprehensive record, entitled Mr. Vanderbilt’s House and Collection (Boston, New York, Philadelphia: George Barrie, 1883–1884), is an invaluable source for the study of the now-demolished residence.

Many of the house’s original furnishings were dispersed when the residence was completely redecorated between 1915 and 1916; others at the time of its demolition in 1946. A refreshed installation at The Metropolitan Museum of Art brings together the largest group of surviving furnishings known, including several that have only come to light in recent years, and provides the most comprehensive insight into one of the country’s most ambitious Gilded Age interiors. Many of these new discoveries were acquired by The Metropolitan Museum through the generosity of Barrie and Deedee Wigmore in whose named gallery they are displayed.

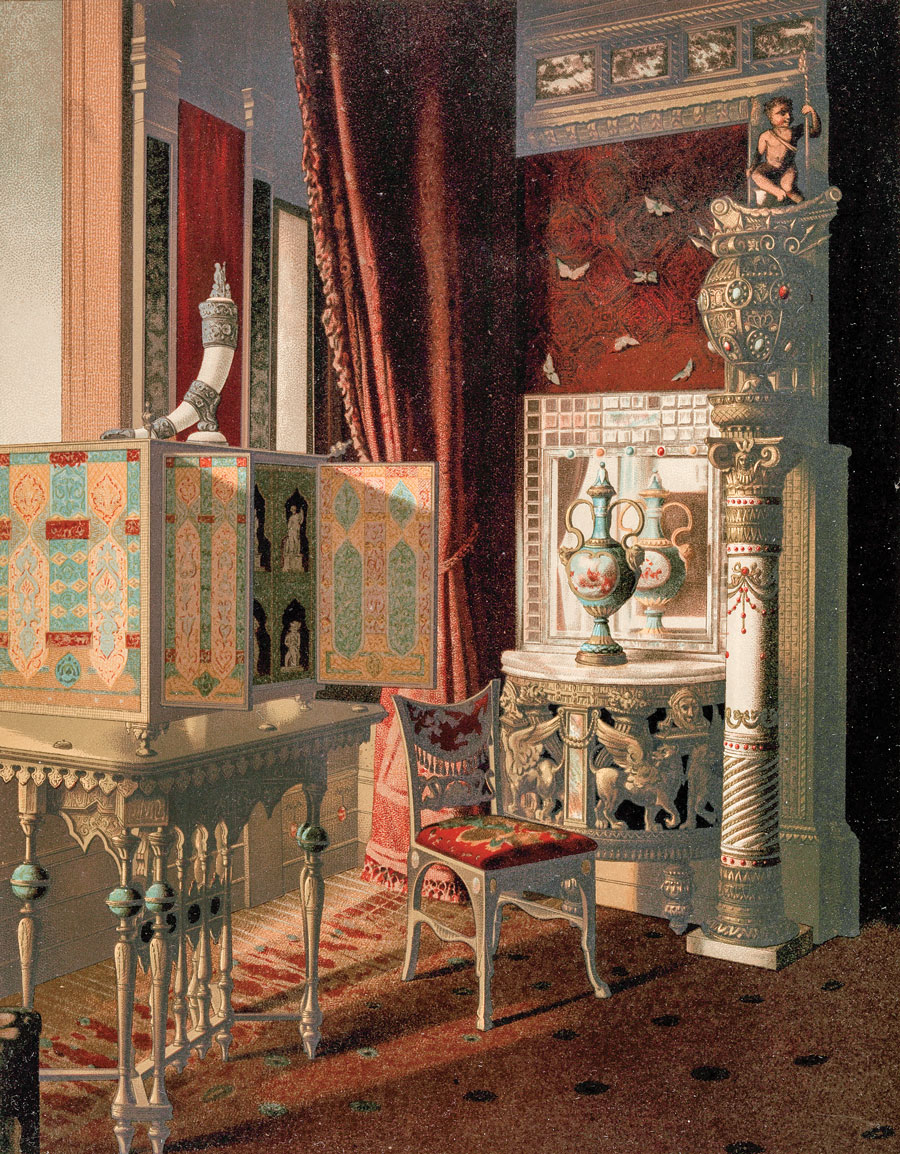

The drawing room was the centerpiece of Herter Brothers’ unified decorative vision. It embodied an eclectic Assyrian Revival theme and a sumptuous crimson color palette, replete with gilding and reflective surfaces. This unusual console is one of only a handful of surviving furnishings of that luxurious space (Fig. 2). As can be seen in the published chromolithograph of a corner of the room (Fig. 3), the console was originally mounted to the wall and was integral to the decorations of the drawing room, echoing the gilded and mother-of-pearl decoration on the frieze above. A central vertical panel of lustrous abalone separates two pairs of opposing Assyrian-inspired griffins along with Renaissance motifs of cornucopias alternating with menacing satyrs’ masks. Jewel-like motifs carved onto the legs and articulated in plaster ornament add further splendor to this richly gilded piece.

- Fig. 4: Herter Brothers (1864–1906), Pair of pedestals from the drawing room of the William H. Vanderbilt House, New York City, 1879–1882. Egyptian alabaster, gilt brass, reproduction red glass jewels. 64-1/4 x 10-15⁄16 x 10-15⁄16 in. The Metropolitan Museum of Art; Purchase, Barrie A. and Deedee Wigmore Foundation Gift, 2002 (2002.298.1, .2).

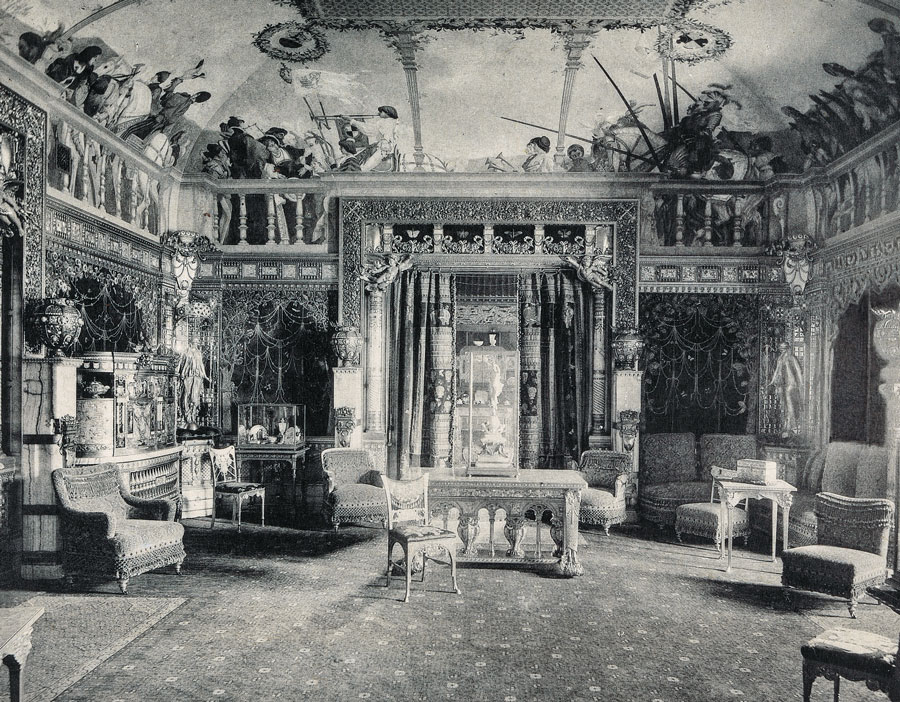

A pair of Egyptian alabaster columns or pedestals (Fig. 4), contributing to the glimmering impression conveyed by the drawing room, were said by Strahan to have been “hung with gold chains set with colored cut crystals.” The tied bowknots and necklaces incised on each column and strung with ruby cabochon “gems” and the Moorish-inspired teardrop motif in gilt bronze—are repeated in the decorations and furnishings throughout the room, and indeed the house. The gilt-bronze capitals lend a fanciful touch as angry birds’ heads support each corner of the plinth. The drawing room may have displayed as many as six pedestals, with pairs flanking each doorway (Fig. 5) and others resting on the floor surmounted by gilt and jeweled vase-form lighting fixtures.

- Fig. 6: Herter Brothers (1864–1906), Armchair from the drawing room of the William H. Vanderbilt House, New York City, 1879–1882. Gilded wood with mother-of-pearl, original cut and voided silk velvet upholstery. 33-1/2 x 27 x 28 in. The Metropolitan Museum of Art; Purchase, Barrie A. and Deedee Wigmore Foundation Gift, 2012 (2012.216).

Perhaps the most remarkable survival from the drawing room is a lady’s bergère (and a related larger, gentleman’s version), complete with its original upholstery (Fig. 6). It is one of two visible flanking the doorway in the interior view published in Artistic Houses (New York: D. Appleton & Company, 1883, Vol. 1, part 2) shortly after it was completed (see fig. 5). The sides of the chair feature two opposing griffins whose spread wings visually connect the sides with the back. They frame mother-of-pearl roundels, centered by a motif of stretched animal hide, shield-like in form, and surrounded by sinuous rope-like elements. The boldly turned legs are in the form of a stylized lotus motif. The original upholstery of voided and cut red silk velvet on a gold ground in the Chinese style is complemented by an elaborate tufted trellis trim over silk fringe and gold cording. It is an extraordinarily rare survival.

Located off the drawing room was a secondary parlor called the “Japanese Parlor” (Fig. 7) Evocative of its foreign namesake, the ceiling was sheathed in golden bamboo set between red lacquer beams. The walls were virtually obscured by built-in étagères with elaborate asymmetrically placed shelving, transforming the room into a repository for a “collector’s treasury.” Although it was altered slightly after its removal from the house at an unknown date, to evoke the impression of carved lacquerwork, Herter Brothers patinated and stained the brass and carved wood cabinet doors of this cabinet with red, gold, and green pigments (Fig. 8). The bottom doors are carved in low relief with stylized blossoms, leaves, and pomegranates in keeping with contemporary Aesthetic design. The brass doors, each a different size and shape depict relief scenes imitative of Japanese landscape painting. The cabinet also features unusual metal hardware with decorative motifs of butterflies and flowers.

A side chair (Fig. 9) is one of several known to survive from the dining room. An iconography of bounty governed the room (Fig. 10), drawn from Renaissance precedents as was popular during the period. The lush swag of flowers, nuts, and berries sculpted on the chair’s crest rail was one of several such motifs unifying the room’s oak furnishings and paneling. The legs and stretchers, however, bear no relationship to European precedents and distinguish this chair as one of Herter Brothers’ most original designs. The stretcher is a complex composition of interlocking parts held in taut balance by equal forces of vertical and horizontal tension. Nineteenth-century seating furniture for dining rooms was typically upholstered in leather for ease of cleaning. The gilded leather upholstery and shaped brass mounts are a modern replacement, based on Strahan’s description of the upholstery as a “dull-red, stamped leather, of special designs, relieved with gold in Cordova fashion.”

Vanderbilt’s library was conceived as a masculine, more solemn space, to house antique works of art and bound volumes (Fig. 11). The walls were covered in fabric and the woodwork and furnishings were subtle, yet sumptuous—all executed in rosewood, carved in a Renaissance mode and inlaid with brass and mother-of-pearl that provided a lustrous reflective element.

An extraordinary table (Fig. 12) was the centerpiece of the library and has become an icon of the Metropolitan’s collection. It complemented the paneling of the room in its use of rosewood and mother-of-pearl inlays. It is simultaneously symbolic of the wealth of its owner and a testament to the skill of Herter Brothers’ craftsmen. The monumental table alludes to Vanderbilt’s power and prestige: its overall shape, lions’-paw feet, and stylized palmettes recall carved stone furniture of the Roman empire; the globes of the different hemispheres on each end imply that Vanderbilt had the world within his grasp; the wreaths enclosing a star with radiating rays in each corner of the table top echo Napoleonic heraldry (Fig. 13). The carved fabric lambrequin at each end, complete with fringe and bows tied from twisted cords, along with the complex incorporation of mother-of-pearl and brass testify to the immense skill of Herter Brothers’ craftsmen. The top with its seemingly random sprinkling of mother-of-pearl stars in varying sizes represents the constellations as they would have appeared over the northern hemisphere on the day Vanderbilt was born, May 8, 1821, a detail that would not have been lost on its late nineteenth-century inhabitants.

- Fig. 14: Herter Brothers (1864–1906), Side chairs from the library of the William H. Vanderbilt House, New York City, 1879–1882. Rosewood, brass, mother-of-pearl, and reproduction upholstery. 14-1/2 x 19-1/2 x 44 in. The Metropolitan Museum of Art; Gift of Barrie A. and Deedee Wigmore, 2014 (2014.530.1.1-.2).

The delicacy of these rosewood and mother-of-pearl side chairs (Fig. 14) belies the heaviness and monumentality of the room and its furnishings, notably the large library table. The design on the chair backs—a star framed by a laurel wreath with berries of mother-of-pearl bound with a bow—is virtually identical to the wreaths that adorn each corner of the library table top (see fig. 13). The turnings of the stiles and spindles on the back are exceedingly finely articulated, with delicate pinecone finials. The sumptuous quality of the room was accentuated by the rich green and gold cut velvet wall covering and upholstery; a replication of the latter was made to cover the side chairs. Removal of the replacement dust cover on the seat’s underside revealed a pencil inscription, “Mr. Vanderbilt’s Library,” typical of those found on Herter furniture, and confirmed their provenance. One of the pair was also inscribed with the date 1879.

The exhibition Artistic Furniture of the Gilded Age showcases more than three dozen examples of furniture from this sumptuous period in the late nineteenth century, and is on view at The Metropolitan Museum of Art through May 1, 2016. For information call 212.535.7710 or visit www.metmuseum.org.

-----

Alice Cooney Frelinghuysen is the Anthony W. and Lulu C. Wang Curator of American Decorative Arts, The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

This article was originally published in the 16th Anniversary (Spring 2016) issue of Antiques & Fine Art magazine, a digitized version of which is available on www.afamag.com. Antiques & Fine Art and afamag are affiliated with InCollect.