At Home With American Art

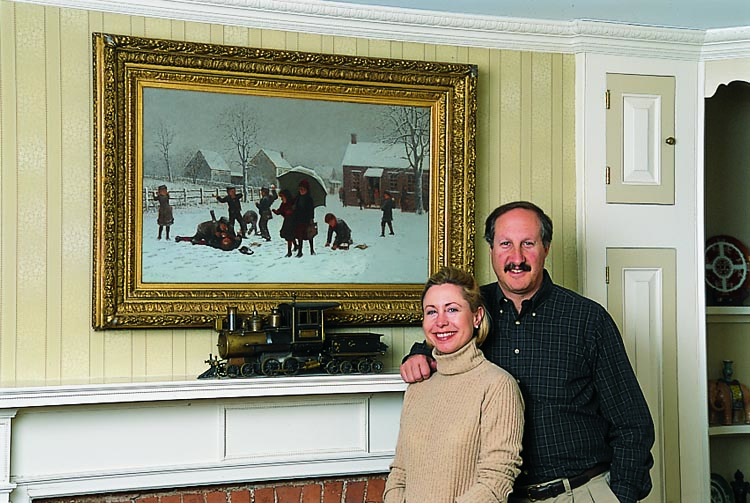

The Collection of Melinda and Howard Godel

Twenty-five exquisite still lifes by American masters—Roesen, Ream, Prentice, Leavitt—line the walls of Melinda and Howard Godel’s expansive dining room. Howard readily admits that he is an “addicted” collector, and when the couple decided to purchase their colonial-style home several years ago, the large dining room with all its wall space was especially appealing, even though the house was falling apart.

“People thought we were crazy to buy the place,” says Howard, “I couldn’t even get a contractor, the work needed to be done was so overwhelming.” Nevertheless, the sprawling home, situated on beautiful pastoral acreage in an historic Hudson Valley hamlet, had classic appeal and plenty of room for the Godel’s burgeoning collection of nineteenth-century American art.

As both a collector and dealer for over twenty years, Howard has the enviable opportunity to follow his passion for American art with a personal collection and a gallery business. It was the topographical details of Hudson River School paintings, introduced to him by friend and fellow dealer Alexander Acevedo, that first sparked Howard’s interest in American art.

Enamored with the Hudson River School, Howard became “basically obsessed” with learning more about American art. He sought to remain focused and to know the field well. Toward this goal, he and Melinda, the granddaughter of an export porcelain dealer whom he met at a Long Island antiques show, frequented auctions, galleries, museums, and shows. He observed the art market, asking trade veterans questions relevant to the historical significance, design elements, and strong points of paintings in order to develop a connoisseur’s eye and understanding of American art. “I grew up middle-class in Queens,” explains Howard, “so I could never understand how people could spend $100,000 for a painting and not educate themselves as to its rarity or place in history.” The “never-ending” process of building a library of art books is also part of the education.

Howard’s impetus to collect and sell art comes from a “passion that remains strong because I’m continually learning and always on a treasure hunt.” In the late 1970s, his first purchase as a collector was a small J.G. Tyler moonlit seascape. He now owns stellar works by top American artists, such as A.T. Bricher, David Johnson, Eastman Johnson, J.G. Brown, and J.F. Cropsey, as well as lesser-knowns of high quality. His business took off after he sold a major Rockwell Kent to the prominent collector Richard Manoogian. What began humbly out of his home has grown to Godel & Co. Fine Art, Inc., specializing in American impressionist, luminist, marine, still life, regional, early modern, and, of course, Hudson River School paintings, now located in an Upper East Side townhouse.

“Howard is a great teacher,” explains Melinda, which is beneficial both when clients seek advice and when assembling a personal collection with his wife. Fortunately, the couple’s tastes are simpatico. “We sacrificed early on in our marriage to buy paintings when our friends were buying cars, stereos, and clothes,” says Melinda, “and we bought what we loved.” Their collection, hung thematically throughout the home, is purposefully categorized into five areas of nineteenth-century American art: still lifes; genre and narrative scenes; animal and wildlife paintings; Hudson River School; and watercolors.

The American art is accented by some of the couple’s other collecting interests including Japanese ikebana (baskets) and netsuke, Chinese export porcelain, silver, and Federal furniture. “I prefer Chippendale,” says Howard, “but Federal is more affordable. We buy from dealers 90 percent of the time because we trust their expertise.”

The key to forming a strong collection, according to the Godels, is to stay focused. Their cohesive collection of nineteenth-century American art developed from an undying passion for the chase and the learning process as well as a natural eye. When it comes to American paintings, “We’re not normal,” says Howard, “we’re crazy collectors.”