Jonathan and Karin Fielding began collecting art and antiques of early America more than twenty-five years ago for their historic home in Maine. Today, the collection comprises several hundred objects, dating from the late seventeenth century to the late nineteenth century. In the Fielding collection, widely regarded as one of the most significant of its kind in the United States, outstanding and rare furniture sits alongside fine needlework, painted portraits, quilts, painted boxes, and other decorative art. Objects lovingly made for daily life by rural New Englanders also feature prominently in the collection: ceramics, handwoven rugs, metal implements, lighting devices, fire buckets, scrimshaw, and weathervanes all variously evince the challenging beauty and surprising ingenuity endemic to early American life.

Over two hundred of these objects are currently on view at the Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens, in the newly-built Jonathan and Karin Fielding Wing, an 8,600 square-foot addition to the Virginia Steele Scott Galleries of American Art. The new wing, designed by Frederick Fisher and Partners, includes 5,000 square feet of gallery space with dramatic, colorful displays that showcase early American paintings, furniture, and works of decorative art. The Fieldings have generously given a number of these objects to the Huntington’s art collections. The ongoing collection exhibition Becoming America: Highlights from the Jonathan and Karin Fielding Collection explores early American history through the lens of these objects, a number of which are illustrated here. Periodic rotations and focused displays will continue to animate the Fielding Wing, which will remain devoted to interpreting this remarkable collection of material.

|

|  |

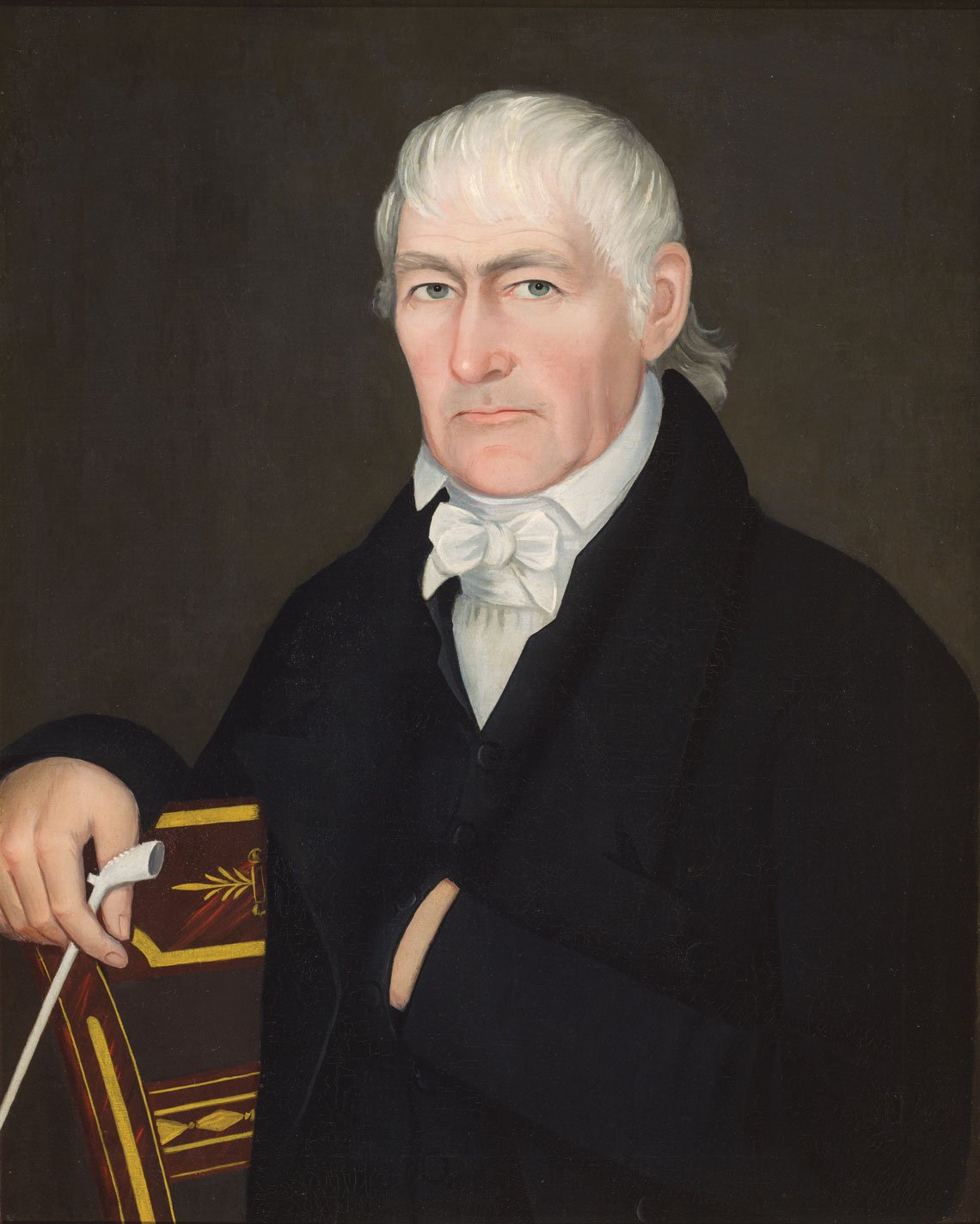

Ammi Phillips (American, 1788–1865), pair of portraits of a man and woman, members of the Van Keuren family, ca. 1825–1830. Oil on canvas, frames: H. 35, W. 29½, D. 3 in. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens. Gifts of Jonathan and Karin Fielding.

|

The Van Keurens were a large and prosperous family of Dutch origin who settled in Ulster County, New York, in the seventeenth century. By the nineteenth century they were wealthy landowners, some of whom owned slaves (full emancipation for slaves in New York did not occur until 1827). As members of the rural aristocracy, the Van Keurens commissioned portraits as emblems of their status, as well as to memorialize themselves for future generations. The prolific portrait painter Ammi Phillips traveled through western Connecticut and Massachusetts before moving to Rhinebeck, New York, directly across the Hudson River from Ulster County. His clear and forthright style, with plain backgrounds and expressively articulated figures, would have appealed to families like the Van Keurens.

|

Grain-painted “Matteson” blanket chest, unknown maker, ca. 1820–1825. Pine, paint, and glass. H. 36, W. 40¾, D. 18 in. Jonathan and Karin Fielding collection.

|

This eye-catching blanket chest illustrates the early nineteenth-century “high style” found in rural Vermont. The faux-grain painting in various hues simulates expensive wood veneers fashionable on federal furniture of the period. The chest stands on high tapered feet and features an elegantly simple carved skirt. Glass pulls adorn the lower single drawer, while the upper blanket chest has a lift top. This chest belongs to a group of Shaftsbury, Vermont, chests with identical construction and similar painting in yellow, green, red, and brown. This group has become associated with Thomas Matteson, a denizen of Shaftsbury; it remains unclear whether Matteson was the owner or maker of two examples in the group inscribed with his name. Such extravagantly painted furniture illustrates the aspirations of everyday Americans to outfit their home with fine furnishings of manifest beauty.

|

Joseph Proctor (American, 1816–1897), Still Life with a Basket of Fruit, Flowers, and Cornucopia, 19th century. Oil on canvas, frame: H. 46, W. 48, D. 1½ in. Jonathan and Karin Fielding collection.

|

This unusually large and exuberant still life has been attributed to Joseph Proctor, an African-American artist active in New York State. The flower stems are weighed down by healthy blooms, while nearby a yellow bird is about to pluck a juicy grape. The watermelon is sliced and ready to eat; ripe peaches and pineapples have been gathered for consumption. This colorful and delectable array, all arranged on a dark ground, can be understood in relationship to still life painting in the eighteenth-century Dutch tradition. Little is known about Proctor, and only a handful of works have been attributed to him. In the 1860 census, Proctor is recorded as an “artist” and his wife Sophia a “housekeeper” in New York City’s Lower East Side.

|

Pair of fire buckets, unknown maker, 1811. Leather and paint, H. 12¼, W. 8⅝, 8½ in. Jonathan and Karin Fielding collection.

|

Fire, which was essential for heat, light, and food preparation in early America, also posed a constant threat to early Americans. Fires in Plymouth, Boston, Williamsburg, and Charleston devastated those communities and prompted numerous building regulations and reforms. Specially designed buckets, made from leather, metal, and other materials, were used by volunteer firefighters, such as members of the Mechanic Fire Society in Portsmouth, New Hampshire. These brave souls would use the buckets to bring water from local wells to douse the flames and prevent the fire’s spread. Such objects were often decorated with elaborate motifs: here, an eagle backs a shield centered with a pair of symbolic shears while clutching the ribbon with the inscription of William P. Gookin, the owner.

Apart from figureheads on ships’ bows, carved full-length portraits in wood were extremely unusual in early America. This example by Asa Ames is all the more rare for its exquisite state of preservation. Little was known about Ames until the 1970s, when census records revealed that his occupation was “sculpting”; he resided in Erie County, New York, and died at age twenty-seven, probably from tuberculosis. Only thirteen works have been securely attributed to him. Many of them depict family members, like this portrait of his niece Nancy. The artist paid careful attention to such details as ears, eyelids, and hair texture—all of which are noticeable on this sculpture.

|

|  |

Asa Ames (American, 1823–1851), Portrait of Nancy Ames Hogue, ca. 1849. Carved and painted pine. H. 35 inches. Jonathan and Karin Fielding Collection.

|

|

| Stoneware, a form of opaque pottery impervious to liquid, was produced throughout early America—particularly in New York and Pennsylvania, colonies settled by the Dutch and Germans. One of the earliest known examples of intact colonial American stoneware, this vessel, found in New York State, features a distinctive checkerboard design relating to imported Westerwald stoneware produced during the period. The cobalt blue decoration suggests Chinese blue and white porcelain, which was extremely popular in Europe and America in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. The alternating blue incising across the surface can also be found on shards excavated at the Kemple Pottery of Ringoes, New Jersey, the Morgan Pottery of Cheesequake, New Jersey, as well as at the Remmey and Crolius potteries of Manhattan during the mid-eighteenth century. The lush blossoms emerging from the ornate flowerpot depicted on the surface of this vessel underscore its ties to Northern European design traditions.

|

Jar, unknown maker, ca. 1750. Stoneware. H. 15, W. 14, D. 11 in. Jonathan and Karin Fielding collection.

|

|

Oval Shaker box, unknown maker, ca. 1820–1840. Pine and maple, tacks, chrome yellow finish. H. 6½, W. 15, D. 11 in. Jonathan and Karin Fielding collection.

|

This large oval Shaker box with six “fingers” (the distinctive “swallowtail” projections that allow the wood to contract and expand) was probably produced at the Shaker community in New Lebanon, New York, the sect’s main spiritual home throughout the nineteenth century. An outstanding example of its type, its size suggests that it may have been used to store a bonnet. Shakers made boxes for their own use and for sale to outsiders as a source of income. Between 1822 and 1836, the New Lebanon community alone made 24,500 boxes in various sizes and colors.

|

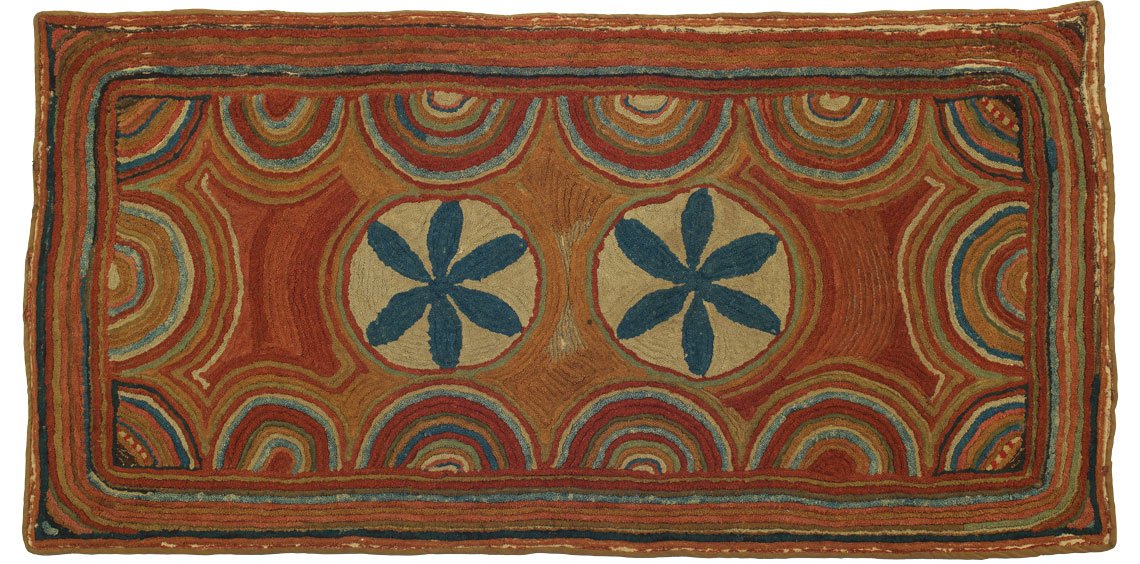

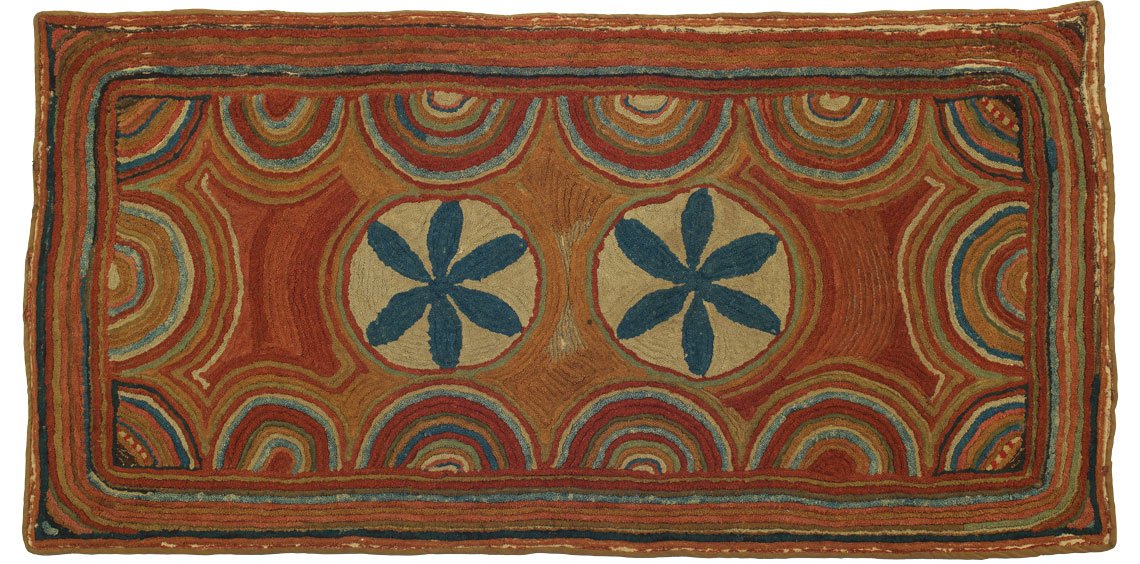

Geometric hearthrug, attributed to Mary Peters Hewins (American, n.d.), ca. 1800. Yarn and shirred wool on linen, 34 x 70 in. Jonathan and Karin Fielding collection.

|

Sewn rugs added vivid color and ornate decoration to a home’s interior. They covered hearths in the summer, decorated tabletops, and cushioned the floor next to beds. This important hearthrug from Maine was made using a fascinating and rare technique, incorporating both yarn sewing and shirring, or gathering that produces texture and elasticity. The composition is lively and inventive: a dynamic scalloped border frames a curvilinear field punctuated by two blue flowers or compass stars. Still retaining its vibrant colors, this rug is initialed “J.H.” in brown ink on the back, likely for James Hewins. The rug has been attributed to Mary Peters Hewins, James’ wife.

Outstanding examples of early American chairs abound in the Fielding collection. They range in time period and geography: you can see an important spindle-back Carver chair from around 1690, an exemplary group of Windsor chairs, and three chairs in the Queen Anne style among other examples. This sturdy, green-painted Windsor chair features a capacious and practical writing arm, with space below the seat for storage of writing implements. The maker of this chair, Ebenezer Tracy, was a Lisbon, Connecticut-based carpenter who achieved renown for his craftsmanship of Windsor chairs. Nails were rarely used in the construction of a Windsor chair; instead, steam-bent spindles and legs were fitted into holes in unseasoned wood that shrank as they dried, tightly gripping the component parts. The result was a lightweight chair of remarkable durability. The wear evident in this example bespeaks its durability over years of loving use.

|

|  |

High-back Windsor armchair with writing arm, Ebenezer Tracy Sr. (American, n.d.), late 18th century. Wood and green paint. H. 36⅞, W. 36¼, D. 31 in. Jonathan and Karin Fielding collection.

|

|

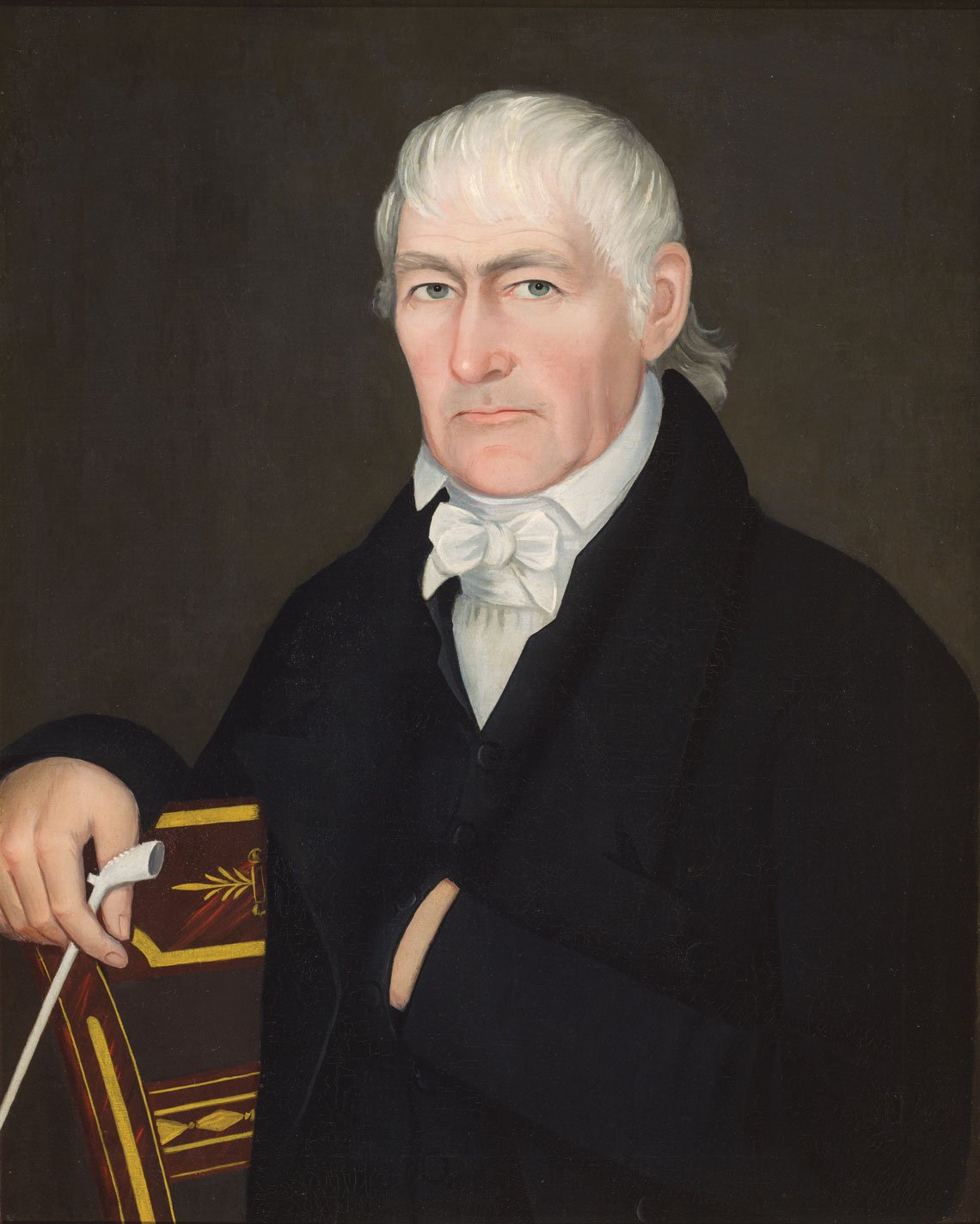

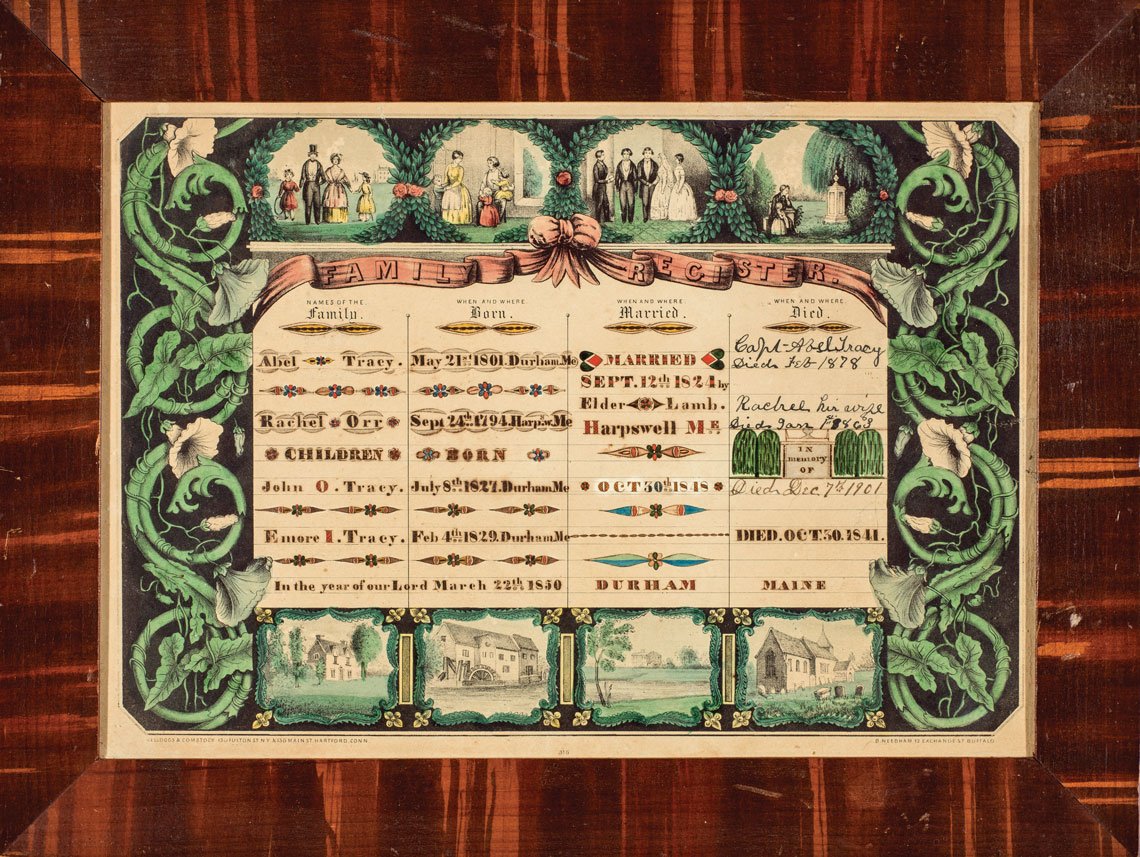

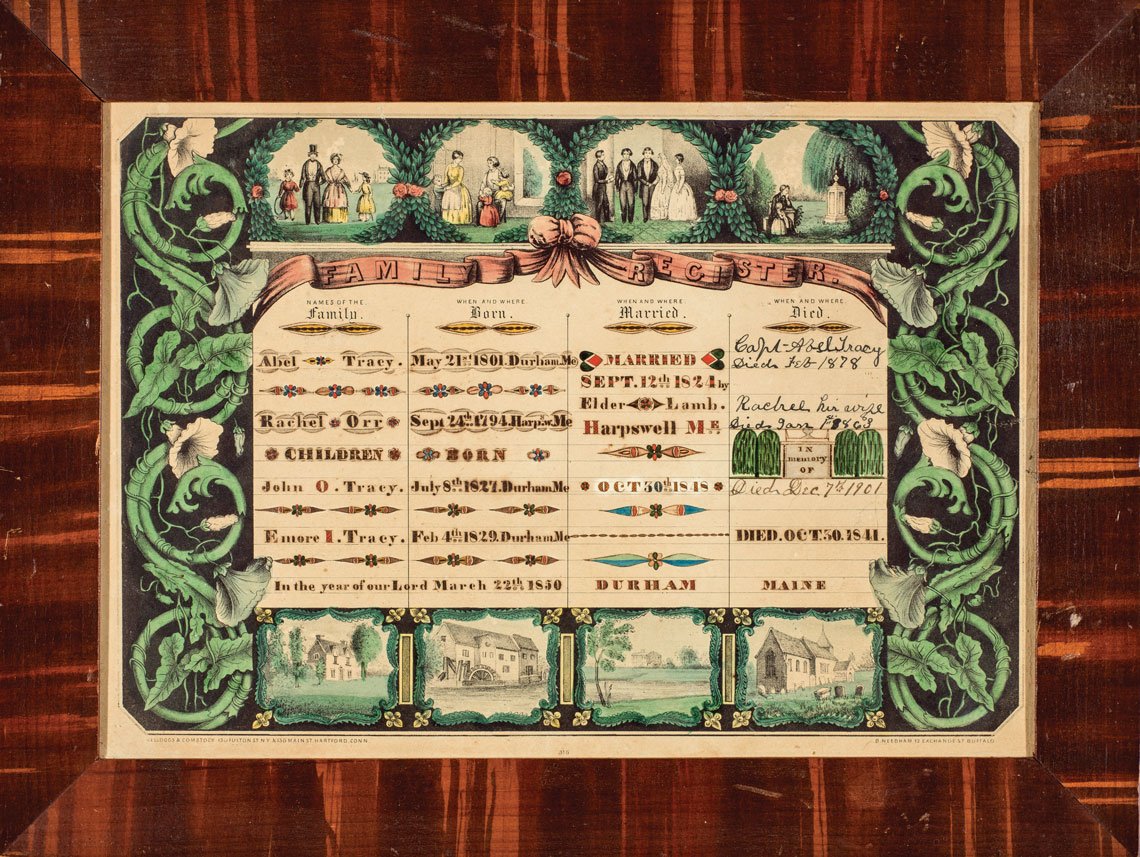

“Heart and Hand,” Tracy family register, unknown artist, Durham, Me., 1848. Watercolor and ink on paper. Frame: H. 12⅜, W. 16½, 1½ in. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens. Gift of Jonathan and Karin Fielding.

|

Several important examples of graphic arts and illuminated documents from early America in the Fielding collection communicate the values that their makers held dear. Vividly decorated family registers, marriage certificates, family trees, and other documents feature ornate vegetal decorative schemes, geometric patterning, and fanciful scrolling flourishes. One such example, a family register by the hand of the so-called Heart and Hand Artist, tells the story of the Tracy family of Durham, Maine. Discrete, precise columns organize the names, birth information, marriage date and location, and place and date of death of the four members of the Tracy family. In block letters interspersed with flowers and hearts, the artist carefully notes the death of the youngest Tracy child, Emore I. Tracy. A later hand fills in the blanks for the other members of the family.

|

| In early America, most homes were dimly lit by the fire in the fireplace, by the burning of dried plants such as reed or rush held erect in specially designed implements, or by the light of candles made from fat or wax. Animal fat, or tallow, was among the least expensive and most readily available materials used for candles, though it smoked and emitted an odor. Beeswax or bayberry candles, while costlier, burned cleaner. This lighting device, made of painted oak and maple wood, functioned using a ratchet to raise or lower the level of two candles. This allowed the light source to be nearer to the task at hand. Its durability and relatively lightweight construction rendered it highly moveable to illuminate different areas and rooms.

|

Ratchet Lighting Device, unknown maker, ca. 1720. Oak and maple wood with paint. H. 30⅜, W. 12½, 7⅛ in. Jonathan and Karin Fielding collection.

|

Carved out of whalebone ribs by the idle crew of whaling ships on long voyages, busks were decorated with elaborate surface carving and then given to sweethearts of the crew back on land. Women would slip the busks into vertical pockets in their corsets, stiffening the garment and giving it structure. In this example, two registers of floral forms emerge from small pots, while below, an oversize bird with a black, fanned tail perches in a young tree. The maker incised the letters “LH” below the tree—likely the initials of his beloved. In its devoted, handmade approach, this object—like the hundreds of others in the Fielding collection—offers a window into the complex and fascinating world of early America.

|

|  |

Scrimshaw busk with initials “LH,” unknown maker, ca. 1835. Whalebone and pigment. 14 by 1½ inches. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens. Gift of Jonathan and Karin Fielding.

|

Chad Alligood is the Virginia Steele Scott Chief Curator of American Art, The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens, San Marino, California.

This article was originally published in the 18th Anniversary/Spring issue of Antiques & Fine Art magazine, a fully digitized version of which is available at www.afamag.com. AFA is affiliated with Incollect.