Becoming John Marin: Modernist at Work

John Marin (1870–1953), one of America’s best known and most admired modern artists, specialized in watercolors and etchings of New York City and the coast of Maine. Yet many of his works have remained unpublished and unseen. In 2013, Norma B. Marin, the artist’s daughter-in-law, gave the Arkansas Arts Center a generous selection of 290 drawings and watercolors that had been preserved in the artist’s estate. Completed watercolors are included in the collection, along with a plethora of sketches and unfinished watercolors not previously shown or published. Now these works can shine.

The John Marin Collection of the Arkansas Arts Center debuts in the exhibition Becoming John Marin: Modernist at Work, opening at the Arts Center on January 26, 2018. The exhibition invites visitors to look over the artist’s shoulder at the process of creation. It brings together drawings and watercolors from the collection with art works on loan from other institutions, reuniting sketches with related watercolors, etchings, or oil paintings, often for the first time outside the artist’s studio.

New Jersey was Marin’s home for most of his life; he was born in Rutherford, the son of a travelling salesman who was seldom home. Young John was raised by his grandparents and two aunts who allowed him many unsupervised hours roaming the countryside with a pencil and a sketchbook. Marin recalled, “I just drew. I drew every chance I got.”1

It was always clear that Marin was an artist, but how he could best make a living was long a question. He tried studying engineering and apprenticing to be an architect. After designing a few houses, he turned to studies at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts and then at the Art Students League in New York. In 1905, Marin moved to Paris, where he made picturesque etchings for the tourist trade. It was while he was chafing at the restrictions of such commercial work that he encountered American photographer and painter Edward Steichen, who was a sort of talent scout for Alfred Stieglitz’s groundbreaking exhibitions of modern art at 291, his gallery in New York City. Steichen instantly recognized Marin’s original artistic genius, which he enthusiastically communicated to Stieglitz.2

Once Stieglitz had seen Marin’s watercolors and etchings, he added the budding American modernist to the stable he was creating of American modernists like Arthur Dove and Marsden Hartley, whose work he exhibited regularly at 291. Stieglitz continued to feature these artists in his later modernist galleries, The Intimate Gallery and An American Place. With the support of Stieglitz, Marin established himself as a leading American modernist. The mature Marin divided his time between his home in Cliffside, New Jersey, and rural vacation locations mostly in Maine. His favorite subjects for watercolors and etchings featured New York’s rising skyscrapers and the glorious meeting of land and sea along the coast of Maine.

Throughout Marin’s career, the artist drew continually. His graphic style varied depending upon whether he was gathering literal visual information, responding to figures in motion, creating a composition, testing out approaches to abstraction, or just drawing for the pure joy of it. Drawing lay behind or within all his completed art works. It is this relationship that viewers can explore in Becoming John Marin: Modernist at Work.

|

| John Marin (1870–1953), Edgewater on Hudson, New Jersey, 1892. Watercolor with graphite on textured watercolor paper, 6¾ x 10 inches. Arkansas Arts Center Foundation Collection; Gift of Norma B. Marin (2013.018.151). |

Architectural subjects were always favorites for Marin. His mature modernist vision was rooted in early drawings and watercolors like this one of places near his home. During Marin’s years apprenticing with architectural firms, he filled sketchbooks with drawings and watercolors of homes, barns, and other buildings. His watercolors like this were softly atmospheric, influenced by the expatriate American artist James Abbott McNeill Whistler (1834–1903). Very few of these early watercolors have been published or exhibited.

|

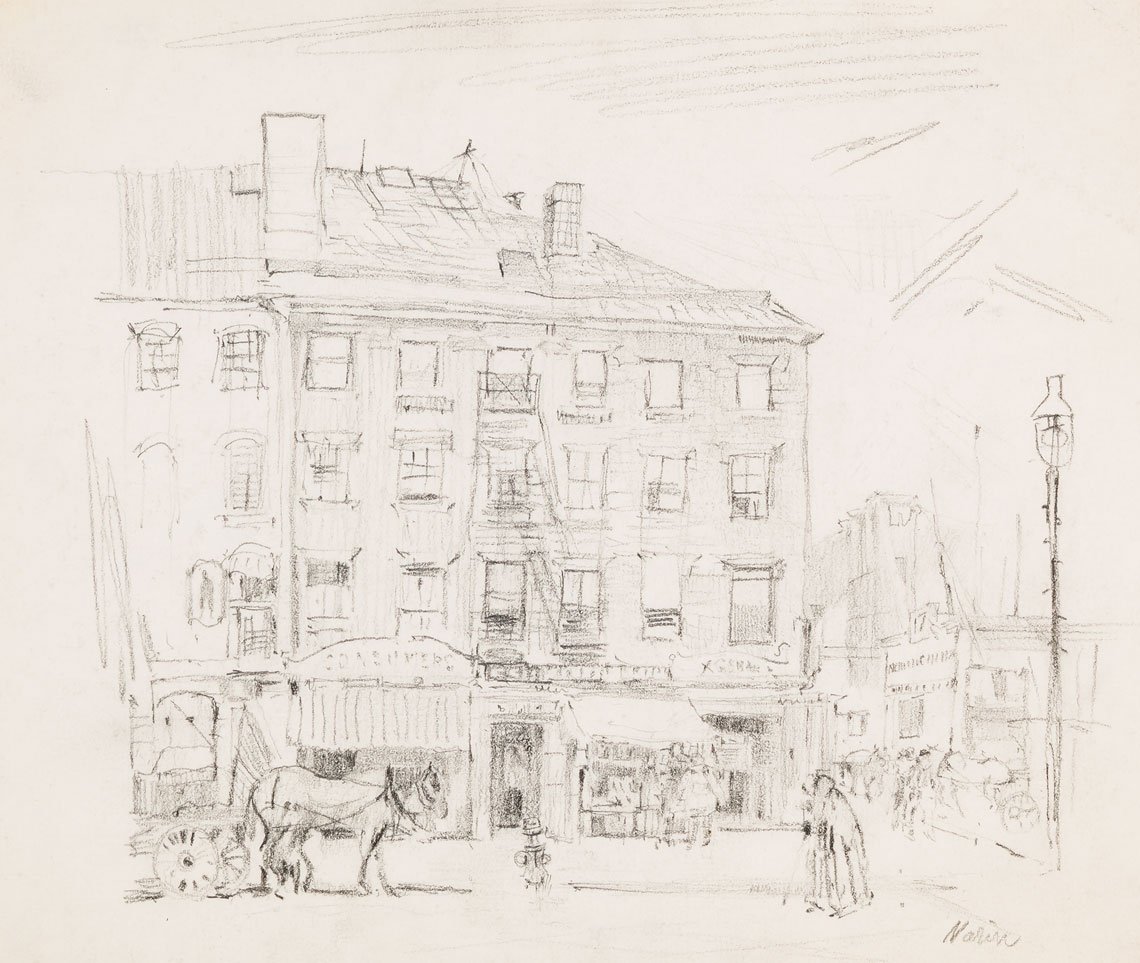

| John Marin (1870–1953), Pine Street, New York, 1895–1905, Graphite on textured watercolor paper, 9 x 12 inches. Arkansas Arts Center Foundation Collection; Gift of Norma B. Marin (2013.018.246). |

This graphite study may surprise viewers familiar with Marin’s mature work–the young artist captured the urban waterfront in unexpected detail. This drawing was made before the 1905 journey to Europe that brought about Marin’s shift from direct realism to abstraction from nature. But throughout his career, place was vital to Marin. Starting when he was a teenager and for the rest of his career, his works used line, structure, and color to catch the spirit of locations he knew well. Pine Street shows the waterfront scene with precision, including the sign identifying the exact pier shown. Research at the South Street Seaport Museum enabled catalogue co-author Josephine White Rodgers to discover where that pier was on the East River. Adjacent to the financial district, these piers dated back to the early seventeenth century. The area became a nexus of commerce that supported the growth of New York City. The background of this striking early drawing includes what may be Marin’s earliest rendering of the Brooklyn Bridge. The great bridge became a modernist icon in his mature work.

|

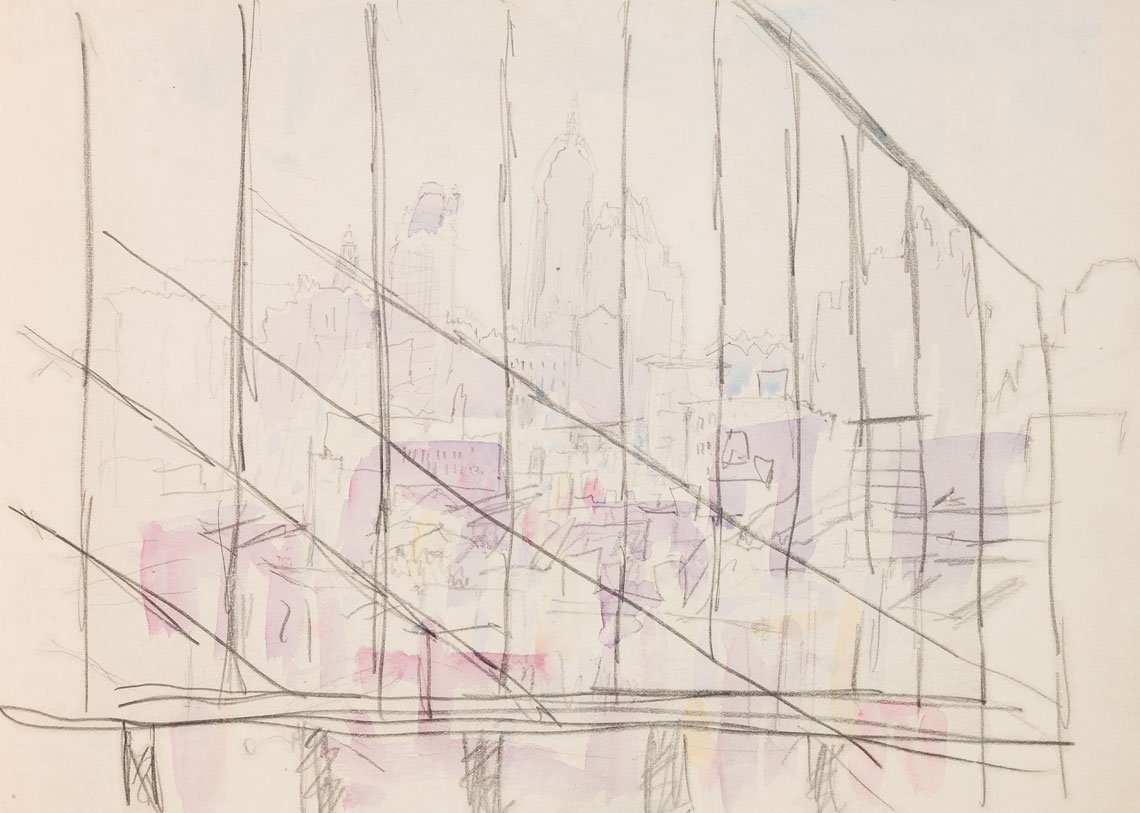

| John Marin (1870–1953), On the Brooklyn Bridge, 1909–1912. Graphite and watercolor on paper, 10 x 14 inches. Arkansas Arts Center Foundation Collection; Gift of Norma B. Marin (2013.018.156). |

When Marin returned from Europe to New York in 1909, he was struck by the many transformations rapidly taking place in his beloved home city. Cars and trucks were replacing horses and tall buildings rose in quick succession. The pedestrian walkway on the Brooklyn Bridge, which had opened in 1883, provided the artist with an ideal point of view to depict the new skyscrapers growing up in lower Manhattan. The view in this watercolor looking through the support cables of the bridge centers on the Singer Tower, which was built at 149 Broadway in 1908, when Marin was away in Europe. Its dominant place as the tallest building on the skyline would soon be taken by the Woolworth Building, and later by the Empire State Building. The once iconic Singer Tower, which stood 612 feet tall, was demolished in 1968.3

In 1912, Manhattan’s City Hall Park was transforming. On one side of the park rose the Woolworth Building, soon to be the world’s tallest building, while on the opposite side work had begun on the Municipal Building. Marin was fascinated by the spectacle of modern construction. He made drawings and watercolors of the two structures under construction and after they were completed. In this sketch of the Municipal Building, cranes and scaffolding are visible atop the new epicenter of city government. The artist must often have been seen standing below the rising towers, in his hands a pencil and a pad of cheap but portable writing paper.

|  | |

| John Marin (1870–1953), Municipal Building, Manhattan, 1912. Graphite on paper, 10 x 8 inches. Arkansas Arts Center Foundation Collection; Gift of Norma B. Marin (2013.018.268). |

| Marin’s drawings of the Woolworth Building and the Municipal Building were the basis for a series of watercolors of each structure. Watercolors of both buildings appeared at the 291 gallery early in 1913. A Municipal Building image went on to the 11th Annual Watercolor Exhibition at the Philadelphia Museum of Art. But the greatest critical attention, then and now, went to the watercolors of the Woolworth Building that moved from 291 to the famed 1913 International Exhibition of Modern Art, remembered as the Armory Show. The series of Woolworth Building watercolors, showing both the progress of the construction and the development of Marin’s abstraction, is now in the collection of the National Gallery of Art. The works progressed from relatively naturalistic images of the building under construction to a sweeping gestural abstract image of the completed edifice. The Arkansas Arts Center’s incomplete watercolor of the Woolworth Building under Construction shows an earlier version of the idea, with Marin using a realistic vantage point before he moved to a less specific perspective in the later completed works. It also shows us the artist sketching the structure of the building on the paper before painting over the graphite drawing. | |

| John Marin (1870–1953), Woolworth Building under Construction, 1912. Watercolor and graphite on textured watercolor paper, 19⅝ x 15⅜ inches. Arkansas Arts Center Foundation Collection; Gift of Norma B. Marin (2013.018.011). |

|

| John Marin (1870–1953), Small Point, Maine, White Mountains in the Distance, 1915. Watercolor over graphite on textured watercolor paper, 16 x 19 inches. Arkansas Arts Center Foundation Collection; Gift of Norma B. Marin (2013.018.022). |

Maine was a place of creative magic for John Marin. At the suggestion of his friend, the etcher Ernest Haskell, Marin traveled from his home in New Jersey to Maine for the first time in the summer of 1914. He painted along the coast of West Point, near Phippsburg. Over the years, Marin and his family would gradually shift summering places in Maine, further north to more and more remote areas. There the artist could work in peace. During the summer of 1915, Marin moved to the nearby Small Point. He loved the juxtaposition there of sea and forest. That same year Marin shocked his dealer and mentor, Alfred Stieglitz, by spending his year’s income to buy an island off Small Point Harbor. The little forested island proved an impractical place to stay, since it had no source of water, but it was beautiful to paint. Later, Marin moved north again to Deer Isle, and in the 1930s, the family began spending summers on remote Cape Split, where the artist purchased a home the family occupies to this day.5

|

| John Marin (1870–1953), Blue Shark, 1922. Watercolor and charcoal on textured watercolor paper, 12⅛ x 16⅛ inches. Arkansas Arts Center Foundation Collection; Gift of Norma B. Marin (2013.018.085). |

John Marin isn’t well known as an animal artist, but, in fact, creatures occur often in his work. From working horses in the streets of New York and Paris to performing elephants at the circus, it is clear the artist was fascinated by a variety of fauna. This striking shark is one of the most unusual of his animal images. Presumably he made the little watercolor in Maine, where he spent his summers on the coast. Perhaps he saw the handsome creature hanging by a dock as a trophy, or washed up on the beach. In the 1890s, Marin had done something similar to create a watercolor of a yellow perch preserved in a sketchbook now at the National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C. Marin was always sympathetic to animals. Before his 1905 journey to Europe, drawings in the Arts Center’s Collection reveal that he spent a lot of time at the Central Park Zoo in Manhattan gazing through the bars into the cages of lions and bears.

|

| John Marin (1870–1953), Landscape, Ramapo Mountains, New Jersey, 1942. Watercolor and charcoal on textured watercolor paper, 14¾ x 17⅛ inches. Arkansas Arts Center Foundation Collection; Gift of Norma B. Marin (2013.018.139). |

.jpg) | |

| John Marin (1870–1953), Ramapo Landscape, ca. 1942. Watercolor, graphite, and black colored pencil on paper, 5½ x 8⅞ inches. Arkansas Arts Center Foundation Collection; Gift of Norma B. Marin (2013.018.229). |

Normally, when Marin was working in rural locations in Maine and elsewhere around New England and the Mid-Atlantic states, he made few sketches. He simply drew right on his watercolor paper and the completed watercolor incorporated the sketch. However, the Arts Center owns works that are an exception to this practice. When he could not retreat all the way from New Jersey to Maine, as when gas rationing made travel difficult during World War II, Marin at times found paintable scenery in the nearby Ramapo Mountains of New York and New Jersey. This beautiful wilderness is so close to New York City that, from some ridges, the Manhattan Skyline is visible. There, Marin made two small watercolor sketches that became the basis for his full-scale watercolor, Ramapo Landscape. It is interesting to compare the changes of detail and color between the swift, simplified sketch and the fully realized watercolor.

|

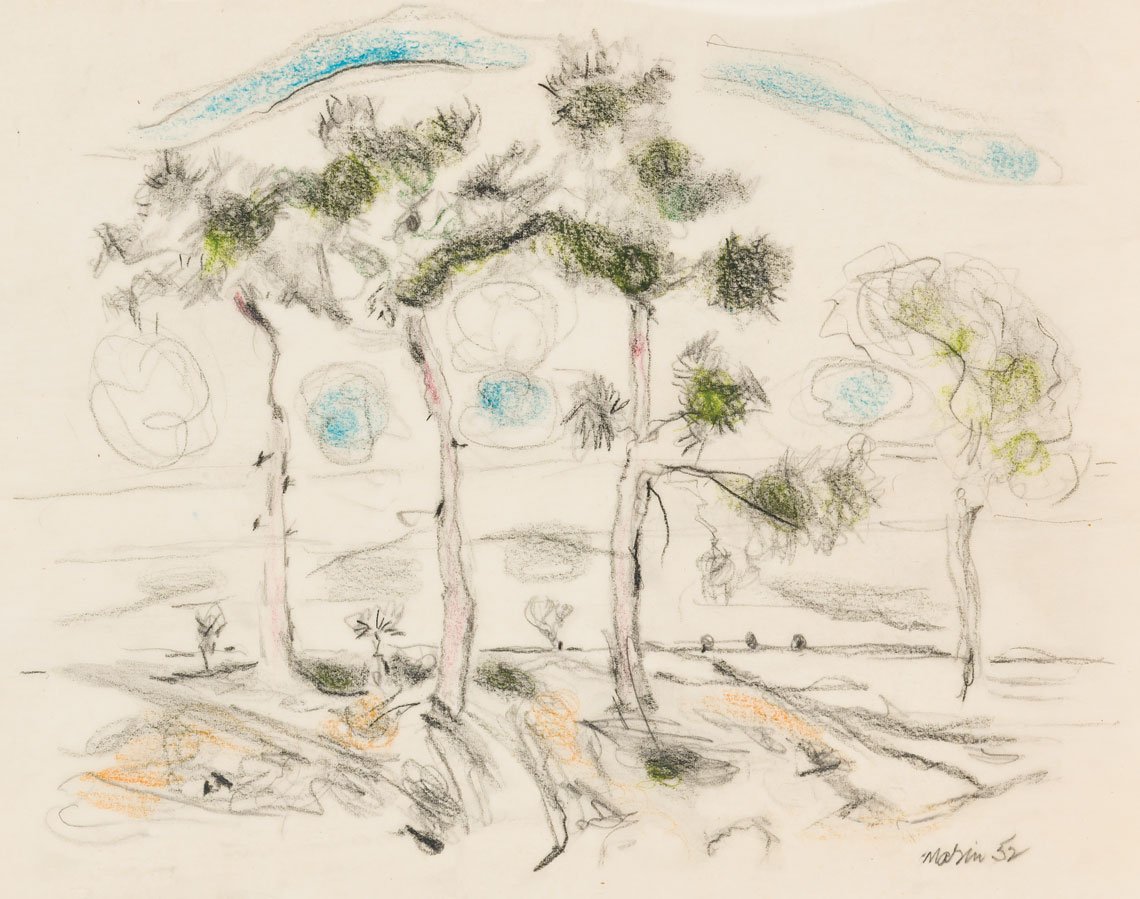

| John Marin (1870–1953), The Three Pines, Blueberry Barrens, Washington County, Maine, 1952. Graphite and pastel on tracing paper, 81-1⁄16 x 11½ inches. Arkansas Arts Center Foundation Collection; Gift of Norma B. Marin (2013.018.222). |

During the summers, Marin and his family were devoted New Englanders. The artist enjoyed such characteristic Maine landscapes as the blueberry barrens that cover the hills in Washington County, not far from the Marin summer home on Cape Split. One of the latest works in the Arts Center’s Marin collection is this drawing of three pine trees in a blueberry barren. As former National Gallery curator and authority on John Marin, Ruth Fine, mentions in her 1990 book on the artist, he seemed to identify with trees, particularly Maine evergreens. Usually he looked to lone trees, but here he gathered three trees together, like the members of his family or a group of friends. They stand companionably, spare and gnarled, but touching each other and full of life.6

Becoming John Marin: Modernist at Work opens January 26, 2018 and runs through April 22, 2018, at the Arkansas Arts Center, Little Rock, Arkansas (www.arkansasartscenter.org). A catalogue of the complete John Marin Collection at the Arkansas Arts Center by Ann Prentice Wagner, Josephine White Rodgers of the Cooper-Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum, and other authorities, accompanies the exhibition. All images shown here are copyright Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/Estate of John Marin and are reproduced with permission.

Ann Prentice Wagner is curator of drawings at the Arkansas Arts Center and curator of Becoming John Marin: Modernist at Work.

This article was originally published in the 18th Anniversary issue of Antiques & Fine Art magazine, a fully digitized edition of which is available at www.afamag.com. AFA is affiliated with Incollect.

2. Ruth Fine and National Gallery of Art (U.S.), John Marin (Washington, D.C.: New York: National Gallery of Art; Abbeville Press, 1990), 75-89, 289–290.

3. Norval White, Elliot Willensky, and Fran Leadon, AIA Guide to New York City (Oxford University Press, 2010), 43.

4. John Marin, John Marin by John Marin, ed. Cleve Gray (New York: Holt, Rinehart, and Winston, 1970), 72.

5. Fine and National Gallery of Art, 229.

6. Ibid, 189.