Inlaid Miniature Chests of the Philadelphia Circus, ca. 1793

"Beyond expectation, beautiful, graceful and superb"

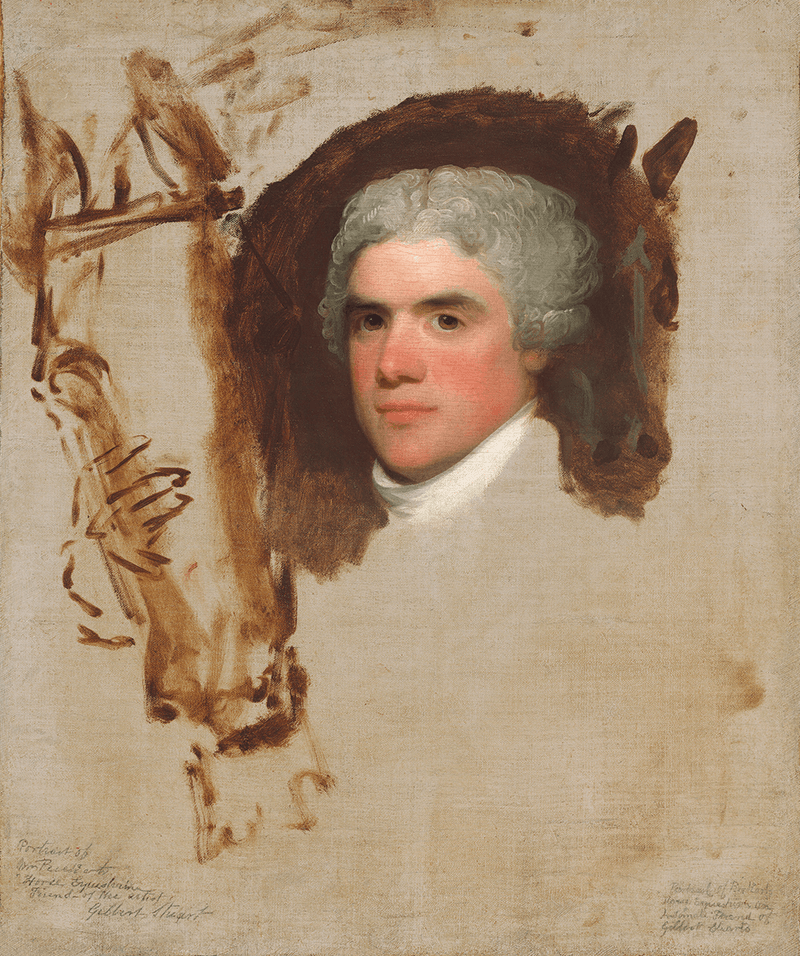

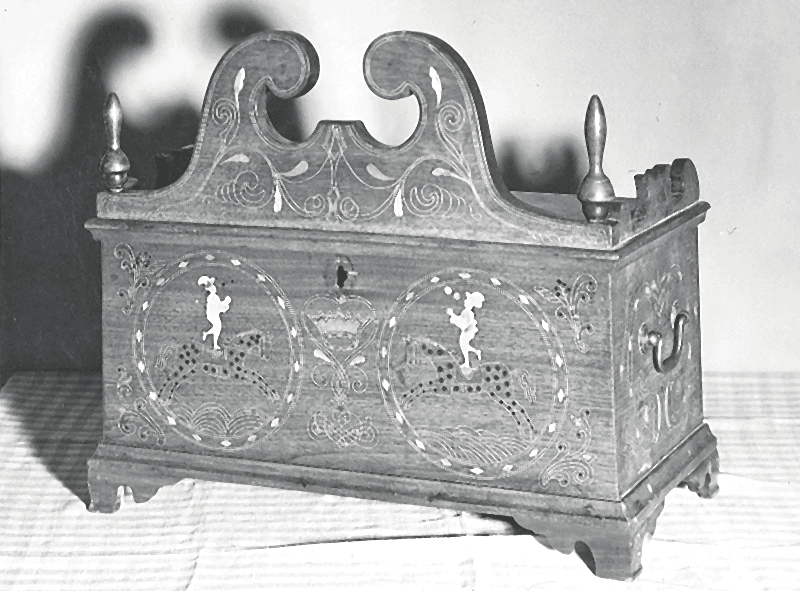

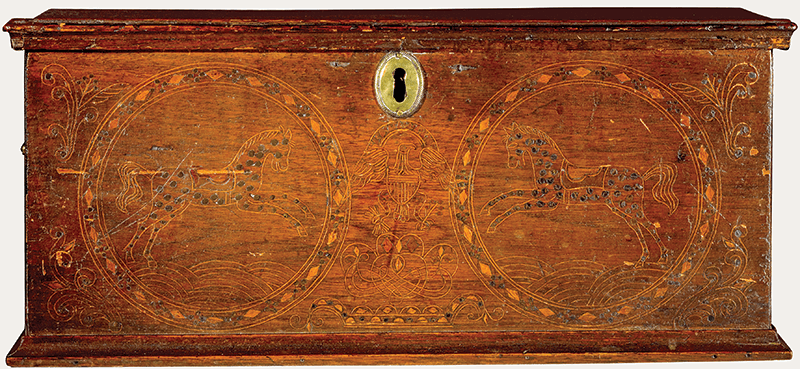

- Fig. 1: “The Jugglers Chest.” Maker unknown. H. 13½, W. 16, D. 8 in. Walnut inlaid with various woods, including maple and sumac; white pine base board. Private collection. Photography David Gentry.

This chest was in the collection of Violette de Mazia (1896–1988) until 1989. Mazia was educational director at the Barnes Foundation and a principal advisor to Dr. Albert C. Barnes (1872–1951). Both were active customers of pioneer Pennsylvania folk art dealer Hattie K. Brunner (1890–1982), as was Henry Francis du Pont (1880–1969). When and from whom de Mazia acquired the chest is presently unknown.

Three privately owned miniature chests inlaid with equestrian performances appear to be the earliest representations of the circus in American decorative arts. Each is meticulously crafted by the same unknown hand. No inlaid furniture made in eighteenth-century Philadelphia and southeastern Pennsylvania is as remarkable in the diversity of its motifs and symbols and in the calligraphic refinement, dynamism, minuteness and sheer quantity of its inlay.

The walnut primary wood is inlaid with a variety of woods—maple, sumac and possibly holly and red cedar among them. Tiny tapered walnut pins secure white pine base boards and other elements.1 Backboards of walnut stabilize blind-mitered dovetails securing all four sides. While extra work, blind-mitering yielded more surface for inlay, as the facades measure only 7 x 16 inches. Each box retains its original bale and rosette brass handles, circa 1790–1800, a time frame consistent with the design and construction of the ogee bracket feet, scroll top, side crests, and moldings of the chest inlaid with jugglers and horses (Figs. 1, 1a,1b), the most complete of the three.

The chests are contemporaneous with the United States career of John Bill Ricketts (?–1800), the so-called “Father of the American Circus” (Fig. 2). “[T]he first rider of real eminence” at the circus in London,2 Ricketts started a riding school in Philadelphia, in October 1792, and a circus the next year. His first performance, on April 3, 1793, was hailed in the local papers as “beyond expectation, beautiful, graceful and superb.” 3 According to The Philadelphia Directory, the Circus quickly became “esteemed amongst the first amusements” of the metropolis. It lauded Ricketts as “perhaps, the most graceful, neat, and expert performer on horseback that ever appeared in any part of the world….” 4 Ricketts and his troupe of trick riders and acrobatic clowns toured other cities of the eastern seaboard and Canada to further acclaim.

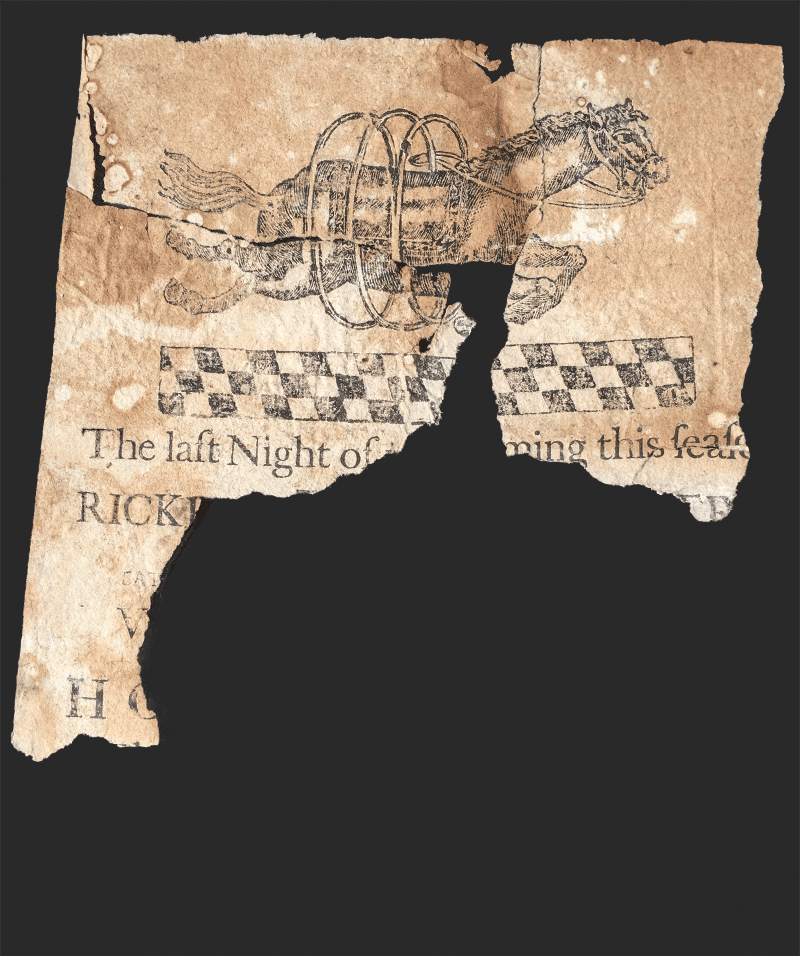

Few ephemera of the Ricketts Circus survive. A token bearing a Ricketts family coat of arms, struck by the local mint, is a rarity of his time in Philadelphia.5 Even rarer is a fragment of a Ricketts handbill depicting a rampant horse (Fig. 3). Unprecedented, however, are the inlaid chests, as they alone show actual circus performances.

The performance depicted on the jugglers chest (Fig. 1a) fits the description on a May 15, 1793, Philadelphia handbill: “Mr. Ricketts, on a single Horse, will throw up 4 Oranges, playing them in the Air, the Horse in full speed.” 6 It also derives from a unique engraving, Mr. Ricketts The Equestrian Hero (Fig. 4). Performers on both chest and engraving wear plumed hats and tailcoats, and stand with one foot on a saddle. The rampant horses, saddles, saddle cloths, cinches, harness, and reins are all similar, as are the positioning and splay of the horses’ legs — not just on this chest but on all three of them.

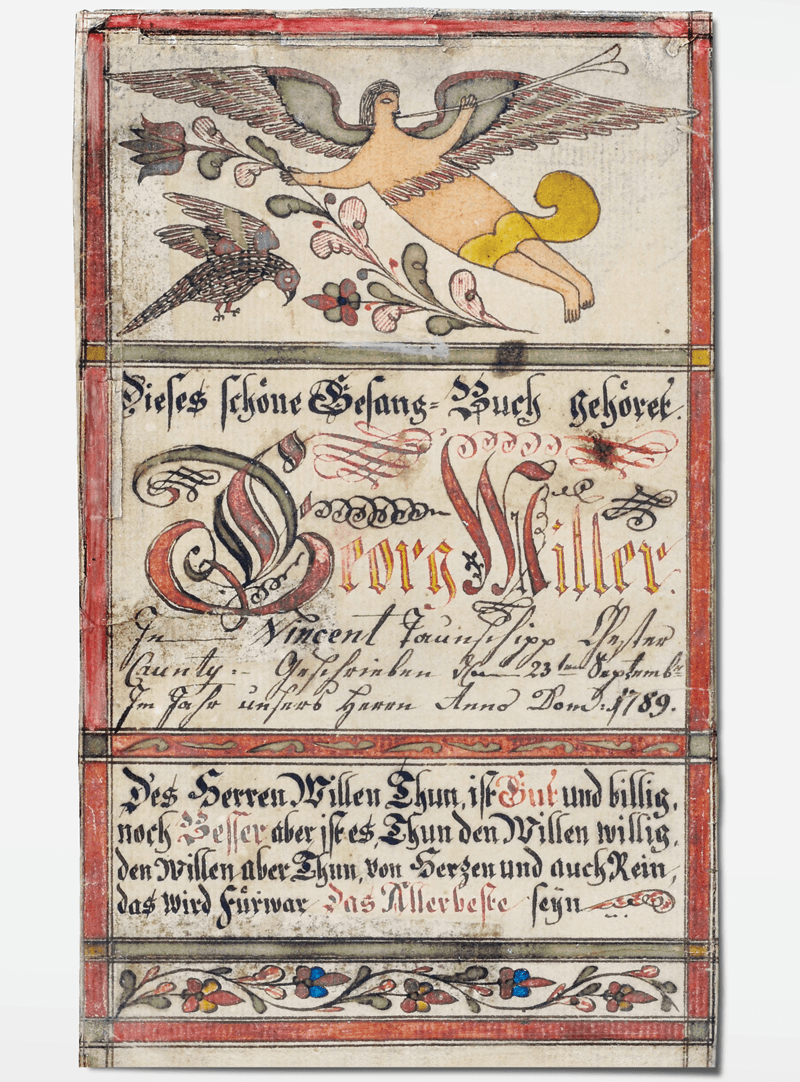

The entrelac designs inlaid on the chests derive from books on calligraphy and penmanship used in Pennsylvania’s German schools.7 These designs also occur as printer’s tailpieces, including one popular with the eighteenth-century Christopher Saur printing shop in Germantown. Similar interlacing can be found on Philadelphia fraktur.8 Samara-like embellished entrelacs, as on the jugglers chest, were favorite motifs of Johann Adam Eyer (1755–1837), a fraktur artist and teacher, active in counties around Philadelphia (Fig. 5). The pointed crown and heart motifs on the jugglers chest are also found on fraktur of southeastern Pennsylvania.9

The jugglers chest retains its ogee bracket feet, a scroll crest inlaid with foliate designs and samaras, and scroll-and-crown side crests (Figs. 1, 1b). Uncarved flame-and-urn finials surmount the chest in a photograph from the files of pioneer Pennsylvania folk art dealer Hattie K. Brunner (1890–1982) (Fig. 6).10 While elements of those designs are all found on Pennsylvania eighteenth-century furniture, no more specific region is suggested by their generic shapes, except that the side crests are reminiscent of those on the small looking glasses sold by John Elliott’s Philadelphia firm to English and German communities via bi-lingual labels.

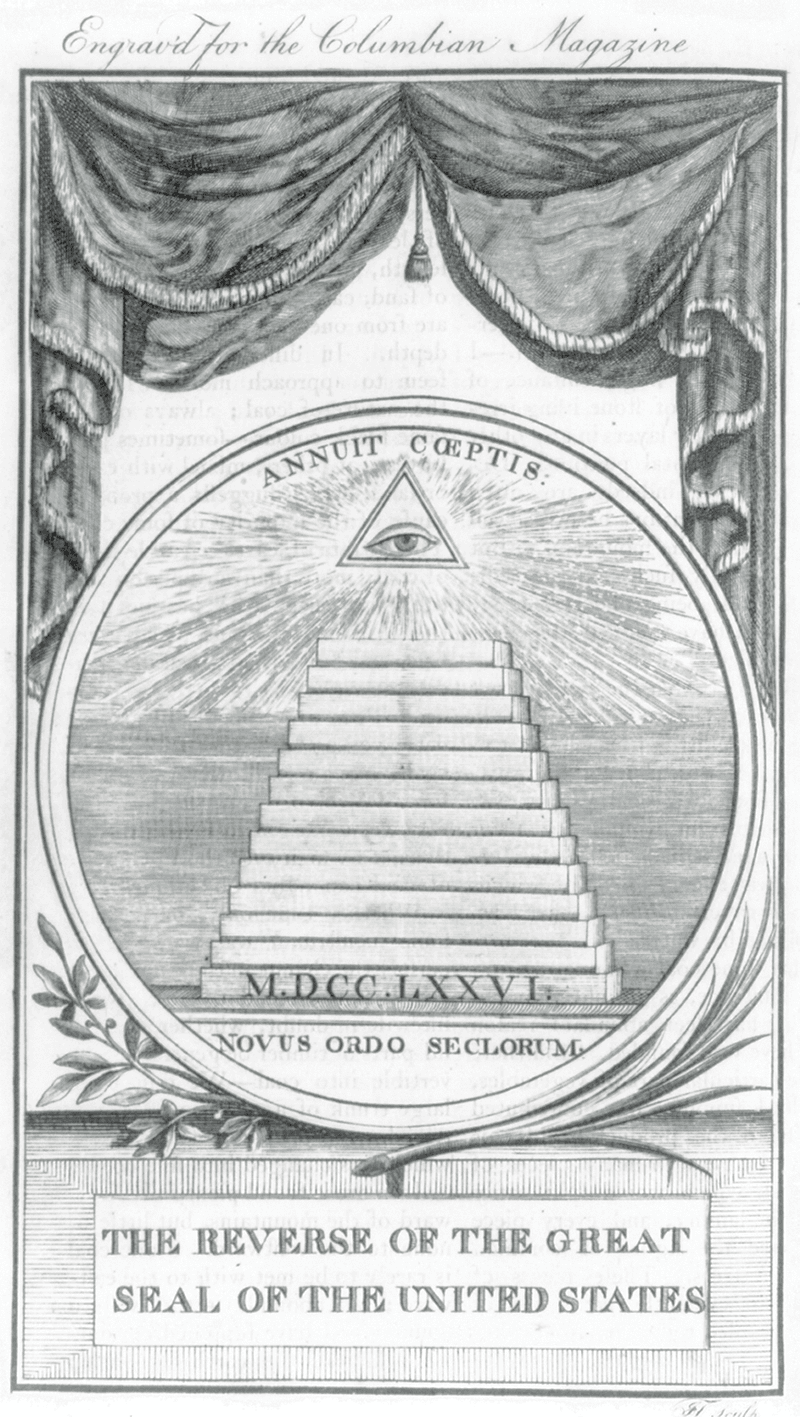

The eagle on the chest also inlaid with horses (Figs. 7, 7a) is appropriate to the period and the circus. George Washington was Ricketts’s most prominent patron. The two accomplished horsemen rode together, and Ricketts feted the President at a birthday ball and on his retirement. When Washington visited a theater, the U.S. coat of arms, from the obverse of the Great Seal, was typically hung over his box.11 The Great Seal had been adopted in 1782 and eagles became popular as patriotic displays in the young Republic. Unlike the Great Seal, the chest’s eagle faces the other direction and has wings inverted rather than displayed. Its origin is a patriotic engraving by James Trenchard (b. 1747) in a 1789 issue of the Columbian Magazine, a popular Philadelphia publication (Fig. 8). Not only are both eagles identical as to direction and inverted wings, but also as to the shape of their legs and how their wing tips protrude beyond the adjacent double lines. The stylized crown or basket intricately inlaid at the base of this chest is similar to motifs drawn by Daniel Schumacher (active 1754–1786) and Johann Konrad Gilbrecht (1734–1812), itinerant fraktur artists who worked at schools and congregations to the north and west of Philadelphia.

The eagle chest was in the Austin and Jill Fine folk art collection, sold in 1987.12 A note tacked to the underside of its lid helps explain the presence of both patriotic and Germanic symbols: “Box from Billmeyer Est. Germantown. Washington slept In the House—over (Inlaid Eagle & 2 Horses).” Washington directed the Battle of Germantown, on October 4, 1777, from the now landmark Michael Billmeyer House.13

In 1783, Billmeyer (1752–1837) and his father-in-law became the de facto successors to the Christopher Saur printing firm, buying its books and equipment. Michael, who was originally from York, moved his printing business into the Billmeyer House in 1789, and lived there through 1831. He became the leading German language printer in America. His clients included everyone from the Pennsylvania Assembly to the Franconian communities in Montgomery and Bucks Counties, whose new hymnbook he printed in 1803. Given the Billmeyer associations with Pennsylvania Germans, Saur, and Washington, it’s not surprising that this chest is inlaid with a federal eagle, a Germanic printer’s tailpiece like Saur’s, and a stylized crown or basket like those on fraktur.

A prominent star of the Ricketts circus also came from York to Philadelphia at about the same time as Billmeyer. John Durang (1768–1822), reputedly the first American-born circus clown and professional dancer, was born in Lancaster and educated at the German school in York before moving at age ten to Philadelphia. Durang also practiced miniature woodworking in Philadelphia. His memoir recounts that he made “a collection of men and women, figures about two feet high…carved out of wood” and “a theatre in miniture [sic].” He started with Ricketts in 1796, initially performing pantomimes and ballets, but soon perfecting his trick riding skills. He was also a sort of jack of all trades at the circus, including “performer, machinist, painter, [and] designer….” 14 But, no link was found between Durang and Billmeyer other than the coincidence of their periods of residence. Durang’s otherwise detailed memoirs do not mention the chests; nor do his drawings of his performances bear resemblance to the inlaid figures. Nonetheless, the accurate depiction on these chests of the figures and their performances suggests that a skilled woodworker with intimate knowledge of the circus, like Durang, could have at least collaborated in their design, if not actually constructing them.

The acrobatic skills of Durang and the other stars of the Ricketts circus are detailed in the third of the group, the chest inlaid with acrobats and horses (Fig. 9).15 Performers in broad-brimmed hats vault over saddled horses with cinches of contrasting woods, clutching reins within fingers individually delineated. Sashes stippled across their waists end in bows lofting behind (Fig. 9a). (Trick riders, not wishing to rely solely on their balance or the centripetal forces of the ring, tucked reins into waist sashes for stability.)

Indistinct prick marks beneath the left acrobat (Fig. 9) are pentimenti of the upended outlines of an earlier horse’s mouth, saddle, and tail. They are barely visible to the naked eye, suggesting that magnified optics, readily available in Philadelphia in this period, may have been used for such detailed work. Not liking how it laid out, the craftsman flipped the wood over to prick out the final design before it was cut and inlaid. These marks are also evidence that the designs were transferred onto the wood matrix by pouncing them through drawings first made on paper or parchment.

The acrobats chest, like the jugglers chest, also has the pointed crown across the heart and, additionally two pyramids, each inlaid with a dot. The latter derive from another symbol on the Great Seal, this one from its reverse: the Eye of Providence. The source likewise appears to be a Trenchard engraving (Fig. 10). As the Eye of Providence is also a Masonic symbol, connoting the all-seeing God, some of these chests may have been made for wealthy equestrian members of the Masonic order. Both Ricketts and Washington fit that description. Indeed, Washington was president of their Philadelphia chapter. Also, part of Masonic ceremony consists of officers covering their hearts with their crowns. But, usually when one sees Masonic emblems on display, it’s not just one, two or three, as here, but a panoply of them.16 So, perhaps the crowns covering hearts on the acrobats and jugglers chests are just further examples of Pennsylvania German iconography. In fraktur, the crown usually appears above the heart, but may have been lowered here to cover the heart in order to make room for the lock escutcheons (figs. 1a, 9a).

Who else might have been possible first owners of these chests? Newlyweds usually got full-sized dower chests, not miniatures. Given the fraktur sources, were they made as elaborate repositories for Geburts or Taufschein (birth or baptismal certificates)? They were not for child play, as too much labor and expense went into making them. Perhaps they were created solely as gifts to circus performers or patrons by a woodworker with connections to the circus, like Durang, who did not ordinarily sell the furniture he made. That might explain why no full-size chests by the same craftsman have turned up and why all of his miniature pieces relate to the circus.

All of the figures and inlaid decoration on these chests appear to have been done freehand, apart from the rings encircling the horses, which were laid out with a compass. (The pivoting mark of the grooving tool that cut the two outer circles is evident under the belly of the acrobat’s horse.)17 Bi-furcated foliate scrolls in the corners are reminiscent of designs found in the relief carving, engraving, and wire inlay on circa 1775–1810 Pennsylvania long rifles. While trades often borrowed designs and techniques from each other, the chests’ designs are far more complex than any found on rifles, so it is doubtful that a gun maker was directly involved in their manufacture. The string inlays are the thickness and width of a playing card: less than .003-inch. As the curves are very tight and without breaks, steam was probably used to bend the inlays into the desired configurations. Whoever cut and set them, the inlays were done so expertly that very few are dislodged two hundred years later. Cross-sections of inlay ending at the top of the scroll board on the jugglers chest reveal troughs that are v-shaped. A very narrow parting tool could have been used to create them, removing just enough wood to accommodate inlay strands, possibly in combination with an engraver’s burin, to enable the very tight curves, especially where interlaced. It is possible the designs on these chests have been borrowed from (or executed by) one of Billmeyer’s contemporaries from the world of Pennsylvania German engraving, like Egelmann, who not only produced books on calligraphy but also printed fraktur.

These chests are remarkable for their inlay and as arguably the earliest representations of the circus in American decorative arts. Given the accuracy of the performers’ feats and dress, their maker either knew the circus first-hand or had access to no longer extant print sources depicting them. Of his identifiable sources, some, such as The Columbian Magazine, were engraved or printed in Philadelphia, but could have been available elsewhere. Moreover, patriotic symbols, such as those from the Great Seal, found their way into both German- and Anglo-work as far away as Harrisburg and beyond.18

Their cabinetmaker—whoever he was and wherever trained—was exceptionally skilled. While his construction methods were not exclusive to the Pennsylvania German tradition, his use of Germanic calligraphic and stylized fraktur motifs, and the Billmeyer provenance to one of the chests, suggest ties to the German printing and fraktur community of greater Philadelphia. Perhaps he also lived in Germantown or its vicinity, or in one of the Franconian communities supplied by Billmeyer. Or, like Durang, he could have moved to downtown Philadelphia from a more distant Germanic community like York or Lancaster. Durang’s talents and the itinerancy of the fraktur artists remind us that gifted individuals could, and did, find opportunities beyond their native communities, bringing with them their skills, wherever learned. The identity of the individual who made these chests remains—for now—a mystery.

There is an ironic and unfortunate postscript to the Ricketts Circus and its founder. Three days after the death of Washington, its most illustrious patron, the circus also perished. A careless carpenter had left a candle burning in the scenery room. The whole caught fire and burned to the ground, on December 17, 1799, leaving Ricketts with a devastating loss of over $20,000. The following year, he was beset by greater misfortune: returning home to England from the West Indies, his ship foundered and Ricketts drowned. But, his legacy as the “Father of the American Circus” survives, as do these chests: “beyond expectation, beautiful, graceful and superb.”

Jay Robert Stiefel is a Philadelphia lawyer and decorative arts historian. He is appreciative to the many individuals and institutions who provided access to their collections and assistance in his research.

This article was originally published in the Summer 2015 issue of Antiques & Fine Art magazine, a digitized version of which is available on afamag.com. Antiques & Fine Art, AFAmag, AFAnews, and AFA Publishing are affiliated with InCollect.com.

2. Isaac J. Greenwood, The Circus, Its Origin and Growth Prior to 1835 (1898; reprinted Washington, DC, Hobby House Press, 1962), 63-64, citing the Memoirs (1824) of clown Jacob de Castro (1758–1815).

3. Dunlap’s American Daily Advertiser (April 4, 1793).

4. The Philadelphia Directory (1794).

5. American Numismatic Society, 1903.27.1.

6. The text of the handbill is reproduced in Andrew Kuntz, “At the Circus: Astley, Ricketts and Durang,” Fiddler Magazine, Vol. 11, No. 1 (Spring 2004).

7. E.g., Carl Friederich Egelmann, Deutsche & Englische Vorschriften für die Jugend (1821).

8. E.g., a bookplate drawn for John Bertsch, in Philadelphia, in 1768, by Sebastian Hinderle, a German émigré who arrived the same year. Approximately 12 x 9 inches, it was exhibited and sold by David A. Schorsch and Eileen M. Smiles at the 2014 Winter Antiques Show, New York.

9. Cf., birth certificates for newborns in various southeastern Pennsylvania counties, ca. 1800, decorated by Johann Jacob Friedrich Krebs (1749–1815) and printed by Jacob Schneider (active ca. 1800), both of Reading, Berks County.

10. The jugglers chest was later in the collection of Violette de Mazia and sold at auction in 1989. Violette de Mazia sale, Christie’s East, New York, April 26, 1989, lot 244. While de Mazia may have acquired the chest directly from Brunner, no confirming documentation has yet been found.

11. Alan S. Downer, ed., The Memoir of John Durang, American Actor (1785–1816) (Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press, 1966), 27.

12. Austin & Jill Fine Auction, Sotheby’s, New York, January 30, 1987, lot 863. Provenance: Billmeyer Estate, Philadelphia; Joe Kindig, Jr., York, Pa.

13. Home to three generations of the Billmeyer family, Freeman’s sold the contents in 1912. The eagle chest may be one of the “2 Toy Trousseau Chests” described in lot 273 in the catalogue. Samuel T. Freeman & Co. (1912). Courtesy of the Germantown Historical Society.

14. Downer, The Memoir of John Durang, 25, 68–69.

15. The chest was sold at auction without provenance. Important Americana, Sotheby’s, January 20–22, 2006, lot 517. The feet and lid are replaced. Inscribed beneath the lid appears to be “Ellie E. Houk.” An individual of that name was elected secretary of the Indiana Convention of the Women’s Relief Group, held April 4–5, 1894, as reported in The National Tribune (Washington D.C., April 26, 1894).

16. Cf., sulfur-inlaid cash box with numerous Masonic symbols, dated 1861, vicinity of Lancaster, Pennsylvania. National Heritage Museum Special Acquisitions Fund (90.3a–b).

17. The spots on the horses could be artistic license or represent dappled breeds. While no specific description of dappled horses for Ricketts or his contemporaries was found, they may have used them. Durang was known to have ridden a bay horse, a breed that sometimes exhibits dappling. There is a watercolor of a lady equestrian performing on a dappled horse in York in 1807. Robert P. Turner, ed., Lewis Miller Sketches and Chronicles (York, Pa: Historical Society of York County, 1966), 62.

18. Cf., tall case clock inlaid with Pennsylvania arms and German motifs and 1815, made by Johannes Paul, Jr., Elizabethville, Dauphin County, Pa. Winterthur Museum.