Beyond Tradition

A Folk Art Collection in New Hampshire

Tucked away in a former pasture amid the hills of New Hampshire a Bauhaus-inspired house is the repository of a couple’s carefully gathered American folk art collection. The soaring angles and planes of the structure provide a gorgeous counterpoint to the folk art within. It’s a gemlike setting for a gem of a collection.

The collectors got their start some forty-five years ago; their impetus was the 1961 101 Masterpieces of American Primitive Painting exhibition at The Metropolitan Museum of Art. One look and they were hooked. Their early acquisitions were similar to those of any new collectors: some hits and a few misses. Over time and with careful study, they bought with greater confidence. They credit dealers like the late Albert Force of Ithaca, New York, and Reggie French of Amherst, Massachusetts, among many others, for their early education. They also bought from the Tillou Gallery in Buffalo, New York. The husband says, “In those days you could still drive around the countryside on a free afternoon and find things in country shops. We did and then spent hours in libraries trying to figure out what we had bought.” The couple’s scrupulous research has given them an encyclopedic knowledge of the artists whose work they own. In many instances it was long after their purchase that they identified the artist of the piece.

|

|

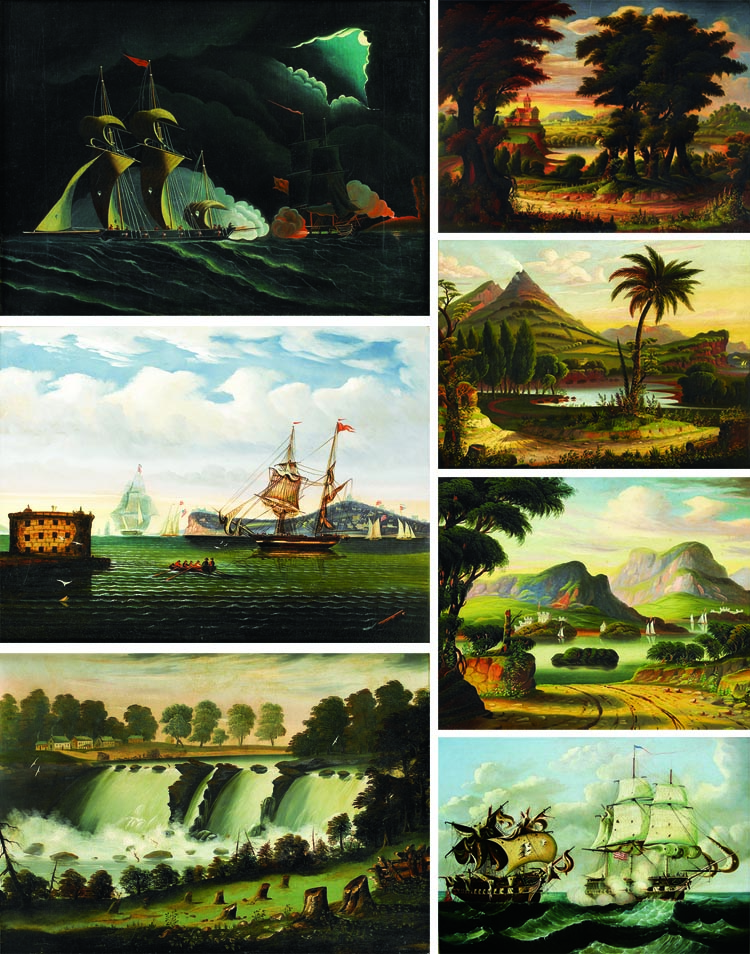

- Among the fourteen paintings by Thomas Chambers (1808–ca. 1866) owned by the couple are: A nocturnal sea battle painted after a James Buttersworth painting; two paintings of Mt. Vesuvius; Castle Island; detail of H.M.S. Macedonian (full view on facing page); Genesee Falls near Rochester New York; and New York Harbor.

- The kitchen is spacious enough to accommodate a sitting area and a fireplace above which hangs an oil-on-canvas view of the 1812 battle between the U.S. frigate United States and the H.M.S. Macedonian by the English-born American primitive artist Thomas Chambers (1808–ca. 1866) (detail shown lower right on previous page). The artist is a favorite of the couple because of his unique abstract style. A pair of sturdy folk art cast-iron dog-form andirons see heavy use.

The husband says it was never their intention to “build a collection;” rather, they acquired what pleased them. “We’ve always had an interest in modern art and design, and our love of American folk art is an offshoot of that.”

Their New Hampshire home, to which they relocated a dozen years ago after the husband retired, bespeaks the couple’s many interests: it is filled to the rafters with a compelling blend of eighteenth through twenty-first-century portraits and landscapes, ceramics, woodenware, and metalware. Light and shadow from the house’s several levels play on the captivating mix of nineteenth-century and mid-twentieth century furniture that combines beautifully with their collections.

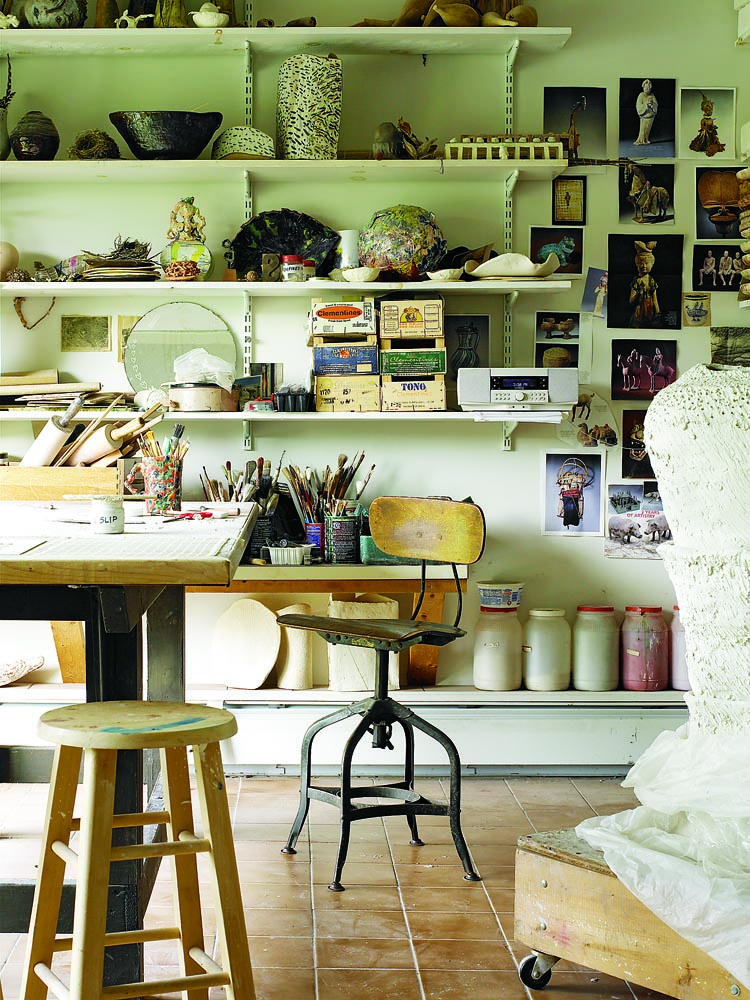

Sprinkled around the house are artworks by the Swiss-born wife, a talented sculptor, ceramicist, and textile artist. She has exhibited and taught sculpture. She confesses to a love of texture that is evident in her work and in the collections that fill the house. Her ceramic bowls in ethereal hues of blue and lavender have an arrestingly tactile grace. Trained in horticulture, she pursued her interest in ceramics when her children were small by taking evening classes. She ultimately achieved a MFA and has received prestigious awards for her work.

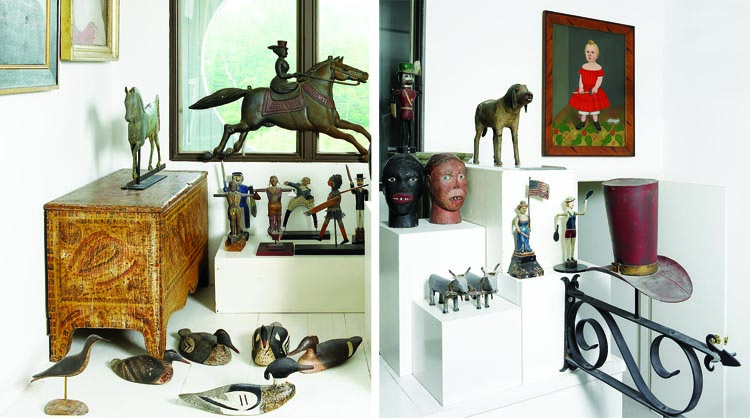

- The couple uses an elevated space above the staircase as a sculpture platform where they display their carved merganser decoys and an index horse, animal figures, whirligigs, and carved heads. The horse and rider in front of the window was an advertising form for the Cincinnati Stove Works. The brown dog from Ohio, circa 1840s, is made of wood with leather ears, a tail, and painted eyes on cloth covered with glass.

Sturtevant Hamblin’s (1817–1884) boy in a red dress plays with a hammer and a toy wagon and stands on a brightly painted floor. The painting hangs above a copper hatter’s trade sign.

From every aspect the house is a visual feast. Color and line, form and texture interact as each object is drawn into the harmonious whole. Art and life intersect here: The joy with which the objects were made and with which the couple assembled them is palpable.

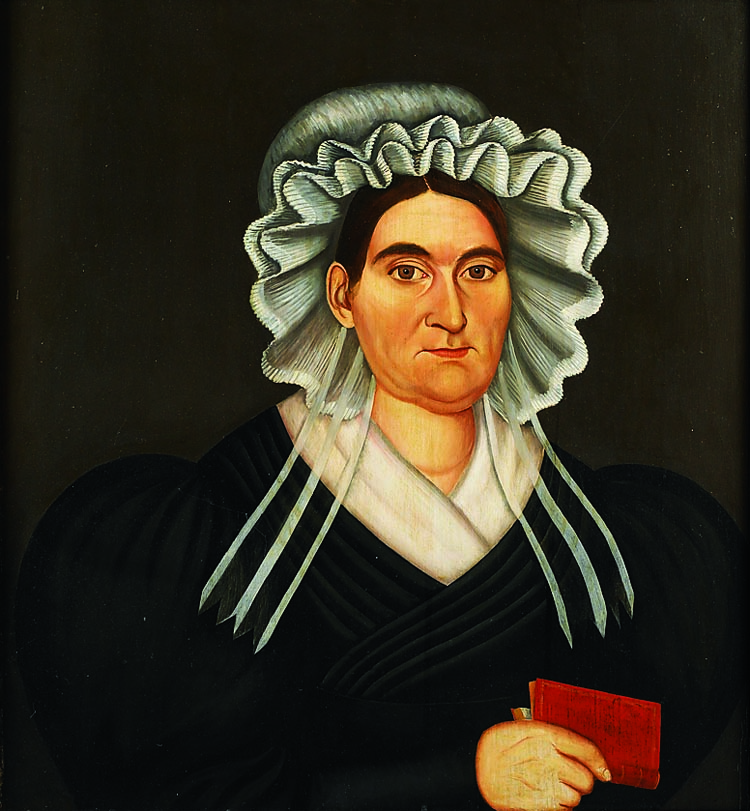

The couple has rarely bought anything they both didn’t like. There are, of course, exceptions. There was the day the husband arrived home from an auction with a portrait that was so heavily overpainted that the wife inquired, “Have you lost your mind?” Not so. It was a portrait on wood panel of Elizabeth Darrow of Holley, New York, signed and dated by Noah North. The husband hoped that the original work might be intact beneath the overpaint. Restoration proved him correct and the couple has lived happily ever after with Elizabeth, portraits of whose mother-in-law and sister-in-law are part of the Shelburne Museum collection.

The husband says, “It’s hard to know just why one responds to a certain piece of art, but perhaps it is the straightforward design, exuberant color, and linearity with little concern about modeling and perspective that makes the work of American artisan painters so appealing.”

- The owners particularly admire the early and highly detailed Vermont landscapes of the self-taught artist James Hope (1818–1892). They have several examples of his work, including a view of Clarendon Springs (above the Shaker furniture) and one of West Rutland (below right), which is the only one in their collection that is signed and dated (1852). The Scottish-born Hope painted views of Castleton (below left), for nearly twenty five years. The owners are interested in his more naïve work of the 1850s. After he was exposed to the aesthetic of the Hudson River School his work became more academic.

The couple lives with comfortable mid-century furniture in keeping with the house itself, though earlier furniture pieces abound. In a niche in one room a group of carved wood animals reside; on an adjacent wall is a selection of chalkware animals. A painted wood rocking horse stands in the foyer by the steel framed staircases. And the house is replete with portraits by masters from the pantheon of primitive artists—Joseph Goodhue Chandler, Samuel Miller, Zedekiah Belknap, and Susan Waters, among others.

An early purchase was the portrait of two children and their spaniel that the owners attribute to Henry Walton. Walton’s techniques indicate a sophisticated sense of color and form and every inch of the picture makes a statement about the sitters—and the artist. The picture has pride of place in the dining room whose cathedral ceiling is filled with weathervanes. Other objects of interest, aside from the Eero Saarinen (1910–1961) dining table and chairs, are a Mennonite sideboard and paintings by Erastus Salisbury Field and one by Joseph Whiting Stock dated 1843.

The couple is also partial to the marine scenes and landscapes of Thomas Chambers because of his unique abstract style. They own fourteen of his works including an oil-on-canvas view of the 1812 battle between the U.S. frigate United States and the H.M.S. Macedonian that hangs above the fireplace in the kitchen, and a nocturnal sea battle after a James Buttersworth painting.

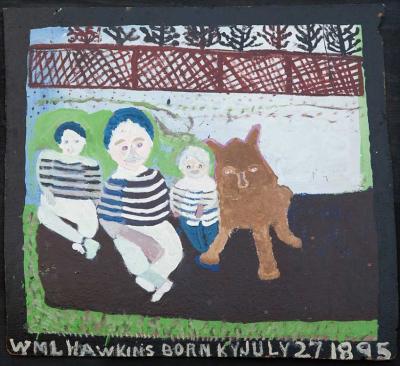

A spacious upstairs landing that overlooks the dining room and leads to the bedrooms and another floor—all of which are filled with paintings—affords multilevel display space. An entire wall is devoted to portraits from the Prior-Hamblin School, including a Sturtevant J. Hamblin portrait of a boy in a red dress and another painting of a boy, this one by George G. Hartwell, in a red dress holding a riding crop. Three portraits—by Royall Brewster, Abiah Warren, and John Usher Parsons—hang on the opposite wall. An adjacent platform is home to a selection of carved birds and animal figures, a group of weathervanes, whirligigs, carved heads, and an impressive hatter’s trade sign from which a glove is suspended.

Despite the fact that the couple has run out of space, the collecting goes on in this house and so does the learning process. The husband says, “We still look. We like to see what’s out there. We visit small libraries and historical societies to learn.” Their eyes and their instincts remain unerring.

This article was originally published in the Summer/Autumn 2006 issue of Antiques & Fine Art magazine. Antiques & Fine Art is affiliated with Incollect.com.