Circles of Learning: The Lifelong Collecting Journey of Bertram K. and Nina Fletcher Little

|

| Fig. 1: Cogswell’s Grant, 1728. Located along the Essex River in Essex, Mass. The Littles purchased the farm house and buildings, which sit on 165-acres, in 1937. |

| |

| Fig. 2: This view of the second floor landing at Cogswell’s Grant shows the Littles’ love of color and texture. The double portrait over the desk, purchased from Childs Gallery, is by Royal Brewster Smith. Nina believed that the painting of a gentleman reading, seen in the adjacent bedroom, is the earliest known portrait by Benjamin Greenleaf. |

It's

hard to know who will pick up the collecting bug and why. People often become hooked not only by the objects themselves, but also by the byproducts of collecting—especially the opportunity to gain new knowledge and to engage with new people. This was certainly true for Bertram K. and Nina Fletcher Little, whose renowned collection of American paintings, folk, and decorative arts can still be seen at the late couple’s home, Cogswell’s Grant, in Essex, Massachusetts, owned and operated by Historic New England as a museum (Fig. 1).

The Littles purchased the property in 1937 as a summer home, and for more than fifty years it served as both an impetus and a setting for a growing collection of paintings and objects (Fig. 2). The eighteenth-century house provided an ideal backdrop for the collection, and the working farm maintained the full flavor of life in an earlier era.

In Little by Little (1998), Nina’s memoir describing six decades of collecting, she explains that her interest in antiques was peaked in 1927 after she had spent a rainy afternoon in the Cambridge Public Library thumbing through N. Hudson Moore’s The Old China Book (1903). It is little surprise that this book had such a profound influence. The book’s opening paragraphs seem to speak almost in Nina’s voice, drawing a picture of the course she and Bert were to follow: “To-day, when our watchword seems to be ‘rush,’ when people who would like to pause and bide awhile are swept along with the multitude, the thoughtful person is likely to ask, ‘How can I best withstand the pressure?’ The device which is of the greatest use is the cultivation of a hobby, an intense interest in some particular subject, let it be birds, butterflies, beetles, old laces, engravings, or china.” 1

|

| Fig. 3: One of Nina’s first purchases was this bowl by Enoch Wood & Sons, 1820–1825, H. 2-1/4, Diam. 9-3/4 in., showing Table Rock, Niagara. |

|

| Fig. 4: Rushlight Club members at Cogswell’s Grant in 1952, returning from collecting rush. |

| |

| Fig. 5: Two examples from Bert’s lighting collection, an eighteenth-century rushlight holder, probably New England, and a late-eighteenth-century chandelier with later candlearms, probably New England, both at Cogswell’s Grant. Lighting devices were Bert’s interest more than Nina’s. He focused his collecting on wooden and wrought iron devices. A similar rushlight holder was the symbol of the Rushlight Club, a drawing of one appearing on the cover of their quarterly magazine. The chandelier, possibly made up of old parts, shows the elegance of form that so appealed to the Littles in utilitarian things. |

Nina was particularly entranced by Moore’s description of early American scenes printed on English Staffordshire earthenwares. Shortly after reading about them she purchased one of her first antiques, a transfer-printed bowl with a view of Niagara Falls, identical to one illustrated in Moore’s book (Fig. 3). Nina recalled visiting a small antiques shop in Ipswich, Mass., where she “caught a flash of blue in a shadowy corner. After hesitant investigation, I emerged triumphantly bearing a shallow 9¾" bowl.” 2 She quickly developed a keen interest in blue and white transfer wares and within four years had published her first article on the subject: “Five Unrecorded Subjects in Blue Staffordshire” for The Antiquarian.3 It was to be the first of her more than 150 books and articles on American decorative arts.

Collectors’ Clubs

Early on, the Littles found the perfect arena for learning new information—collectors’ clubs. Describing their collecting in the 1930s, Nina wrote: “[T]he most stimulating development of the decade, as far as we were concerned, was the formation of four different collectors’ clubs in the Boston area from 1932 to 1934. Monthly meetings afforded convenient places to foregather, encouraged the study of unusual pieces from the members’ collections, and provided the opportunity to meet congenial people with whom to exchange ideas and information.” 4 The four clubs were the Early American Glass Club, the Wedgwood Club, the Rushlight Club, and the China Students’ Club. These last two may have been the most pivotal in their collecting lives.

The Rushlight Club, founded in November 1932, was the first of the collectors’ clubs and the model for the others that followed. It started as an informal gathering of eight collectors of early lighting equipment, and Bert and Nina soon became members. Meetings were often held at members’ homes and began with informal discussion over lunch. Members were then called to order by the ritual lighting of a rush, followed by club business and a formal presentation by a member or guest. The Rushlighters met at least twice at Cogswell’s Grant, once in 1952, and once in 1966. On both occasions the day began with members picking rushes in the fields (Figs. 4, 5).

|

| Fig. 6: Tin-glazed earthenware bowl, England, possibly London or Bristol, 1720–1730, H. 7-1/2, Diam. 12-3/4 in. Nina purchased this bowl in 1958 from the renowned New Hampshire dealer Roger Bacon. Always curious and interested in recording an object’s history, she asked Bacon who his English source was and she wrote to the Oxfordshire dealer, who explained he had purchased the bowl at a country house auction near Chepstow, Monmouthshire. He thought the castle decorating the bowl probably represented one of the many castles that lined the Welsh border nearby.7 Nina carefully recorded this information in her collections files. The heavily restored foot in no way detracted from the Littles’ interest in the piece and, as was typical, they preferred to leave the old repair alone rather than restore it. |

While blue and white transfer printed Staffordshire pottery was Nina’s first collecting interest and remained a focus throughout her life, as she learned about different types of ceramics from members of the China Students and Wedgwood Clubs, her interests expanded, adding “depth and variety” to her collection (Figs. 6, 7).5

Friends and Dealers

The Littles also expanded their knowledge through informal gatherings with various people who shared their interests. Their guest book reads like a Who’s Who of the antiques world, with a host of collectors, dealers, and curators recording their visits year after year. Christopher Monkhouse, recently retired from the Chicago Art Institute, remembers when he and three fellow curators would make their annual summer call at Cogswell’s Grant in the 1970s and 1980s. The afternoon would begin with insider gossip, often followed by a house tour, and discussion of the Littles’ recently acquired treasures. Tea was served, as a breeze played an Aeolian harp in an upstairs window and the smell of freshly mown hay wafted into the room as the group talked about exhibitions, research, and publications.6

Among the Littles’ closest friends were Lura and Charles Watkins. Like the Littles, Lura and her husband were active members of collectors’ clubs. And like Nina, Lura Woodside Watkins was a tireless researcher, writing extensively and publishing books on American glass and New England pottery; her Early New England Potters and Their Wares (1950) remains the standard on the subject today (Fig 8).

|  | |

| Fig. 7: In the dining room at Cogswell’s Grant, a Staffordshire cheese dish by James and Ralph Clewes is overshadowed by the Littles’ outstanding collection of American redware displayed on a red-painted hutch. | Fig. 8: Redware pitcher, 1788, possibly North Orange, Mass., H. 7, Diam. 6-1/2 in. This pitcher, because of its dated inscription, “Joseph Goodell 1788,” was a prize for any serious collector of early American pottery. Nina purchased it in 1969 and kept a letter tucked inside it from her friend Lura Woodside Watkins. The letter began with Lura saying how much she had enjoyed dinner with Bert and Nina the previous week, then went on: “I think that pitcher is the finest thing you’ve found. It certainly looks American, too, and could be very early. I hope you’ll be able to look into it further.” 8 Nina did so, and discovered that Joseph Goodell had lived from 1735 to 1829 in Warwick, New Hampshire. His son Zinus and his grandson lived in nearby Orange, Massachusetts, a town known to have had working potteries in the eighteenth century. Her notes end with the question: “Was the jug made in Orange or another local pottery nearby for Joseph Goodell?” 9 |

| |

| Fig. 9: Dealers Rocky and Avis Gardiner unpacking their car at Cogswell’s Grant, August 1949. The Gardiners developed such an acute sense of the Littles’ taste that every October Bert and Nina went to the Gardiners’ booth at the Ellis Memorial Antiques Show in Boston for the Christmas presents they purchased for each other.10 |

The Littles also worked closely with dealers. Eventually a core group formed, many becoming friends. Among these were Rockwell and Avis Gardiner of Stamford, Connecticut, who were invited to Cogswell’s Grant each year for a weekend visit (Fig. 9). After one visit, Rocky wrote in the guest book: “Each visit enriches us in friendship and knowledge.”

Charles and Ellie Childs were also dealers who became longtime friends, and their Childs Gallery on Newbury Street in Boston was the source of many of the Littles’ prized objects. In the 1960s, when Charles Childs was thinking about retirement, he hired Carl Crossman as an assistant and eventually sold the gallery to him in 1969. Subsequently, Carl became a close friend of Nina’s and continued to find objects for the Littles’ collection, including a pair of portraits by Ammi Phillips, which Nina felt were the greatest pair she’d ever seen (Figs. 10, 11).

As much as they learned from others, Nina and Bert learned most from each other; their collection, research, and legacy were the products of a lifelong partnership. They died within months of each other in early 1993. While the collections from their home in Brookline were the material of two legendary sales at Sotheby’s, their collections at Cogswell’s Grant remain intact. One of thirty-seven properties belonging to Historic New England, Cogswell’s Grant is open to the public, Wednesday to Sunday, between June 1 and October 15. For information call 978.768.3632 or visit www.historicnewengland.org.

|  | |

| Figs. 10, 11: Col. Joseph Dorr and Sarah Bull Dorr, Ammi Phillips, Hoosick Falls, N.Y., 1814–16. Oil on canvas. H. 40, W. 33 in. In 1969, soon after Carl Crossman took over Childs Gallery, a couple from Hoosick Falls, New York, brought these two portraits into the showroom on Newbury Street in Boston. Carl identified the paintings immediately as by Ammi Phillips. He took them to Nina, who reportedly said that although she did not care for Phillips’ work, these were among the greatest portraits she had ever seen. When he delivered the paintings to her home in Brookline, Nina, knowing that Bert would complain that there was no place to put the portraits, asked Carl to hide them in an upstairs bedroom. Packing to go to Cogswell the following spring, Nina sent Bert to retrieve the paintings, knowing by then it was too late to return them. Bert’s role was to be the voice of reason. As Nina once jokingly told Carl, “If I listened to Bertram K. Little, I wouldn’t own a thing!” 11 | ||

|

| The Littles purchased the shirred rug in front of the fireplace from their friend, the Connecticut dealer Mary Allis. They copied the lines of an eighteenth-century wallpaper valance and used reproduction wallpaper to create the valance that now hangs on the bed in the forefront. |

|  | |

| Young Girl, possibly Jane Hutch or Hutchins, attributed to Zedekiah Belknap (working ca. 1810–1850), 1810–20. Oil on panel. H. 24, W. 17-3/4 in. Nina Little acknowledged that Zedekiah Belknap’s paintings are uneven, although she found his portraits of children to be “delightfully naïve.” | Weathervane cock, possibly Bethel, Maine, area, late eighteenth century. H. 22, W. 34 in. When the Littles discovered that this “dignified” cock had supposedly come from a steeple in West Bethel, Maine, they headed north to learn more. Nina noted “This turned out to be one of our unsuccessful quests, although we met many kind people who tried to be of help.” |

|

| Many of the Littles’ collecting interests are present in this bedroom: early portraits, hooked and woven rugs, early furniture, painted chests (on the far right), lighting, decoys, and redware, used in this case, undrilled, as a lamp. |

|

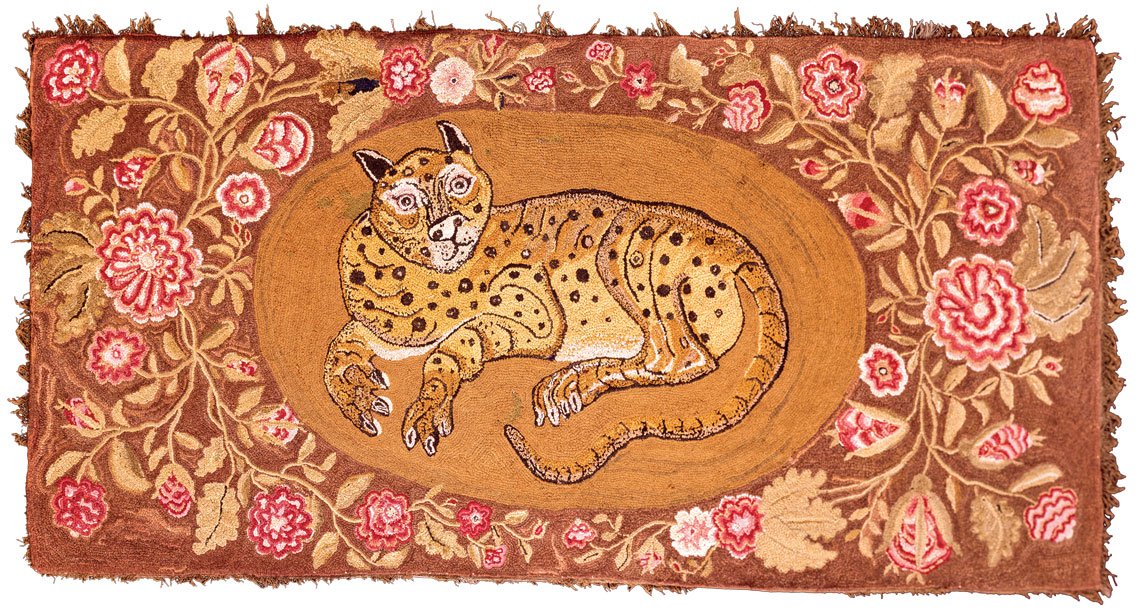

| Hooked rug, probably Vermont, 1850–1890. Wool, jute, linen. H. 34-1/2, W. 67 in. The Littles began collecting hooked rugs in the 1920s and had been doing so for more than forty years by the time they found this one in Ashley Falls, Vermont. Nina admired the “unconsciously humorous” leopard “sprawling nonchalantly.” |

Nancy Carlisle is senior curator of collections, Historic New England.

This article was originally published in the Autumn 2017 issue of Antiques & Fine Art magazine, a digitized version of which is available at afamag.com. AFA is affiliated with Incollect.

2. Nina Fletcher Little, Little by Little: Six Decades of Collecting American Decorative Arts (New York: E. P. Dutton, Inc., 1998), 2.

3. “Five Unrecorded Subjects in Blue Staffordshire: A Collector Assigns Marked Specimens of Three American Views and Two Genre Subjects of ‘Old Blue,’” The Antiquarian, March, 1931.

4. Little by Little, 25.

5. Little by Little, 30.

6. Christopher Monkhouse, interview with Nancy Carlisle, July 7, 1995. These visits occurred in the late ’70s and ’80s, and included Monkhouse, then curator of decorative arts at the Museum of Art, Rhode Island School of Design; Morrison Heckscher from the Met; Wendy Cooper, then at the MFA Boston; and Peter Spang, curator at Historic Deerfield.

7. Roger Warner to Nina Fletcher Little, April 9, 1958. Bertram K. and Nina Fletcher Little papers, Historic New England Library and Archives. Hereafter Little family papers.

8. Lura Woodside Watkins to Nina Fletcher Little, September 2, 1969. Little family papers.

9. Little family papers.

10. Carl Crossman, interview with Nancy Carlisle, July 7, 1995.

11. Ibid.