Converging Lines: Eva Hesse and Sol LeWitt

Exhibit: Converging Lines: Eva Hesse and Sol LeWitt

When: February 23–May 18, 2014

Where: Blanton Museum of Art, The University of Texas at Austin, 200 East MLK, D1303, Austin Texas

Contact: blantonmuseum.org; 512.471.5482

Long before Eva Hesse (1936–1970) and Sol LeWitt (1928–2007) secured reputations as two of the most significant American artists of the postwar era, they were among each other’s best champions and confidantes. In the late 1950s, Robert Slutzky, an architect who once taught at the University of Texas at Austin, introduced them one evening at a party in New York. Their friendship did not develop immediately; as LeWitt later recalled their initial encounter: “I was sort of wowed by her, but unfortunately she wasn't wowed by me!”

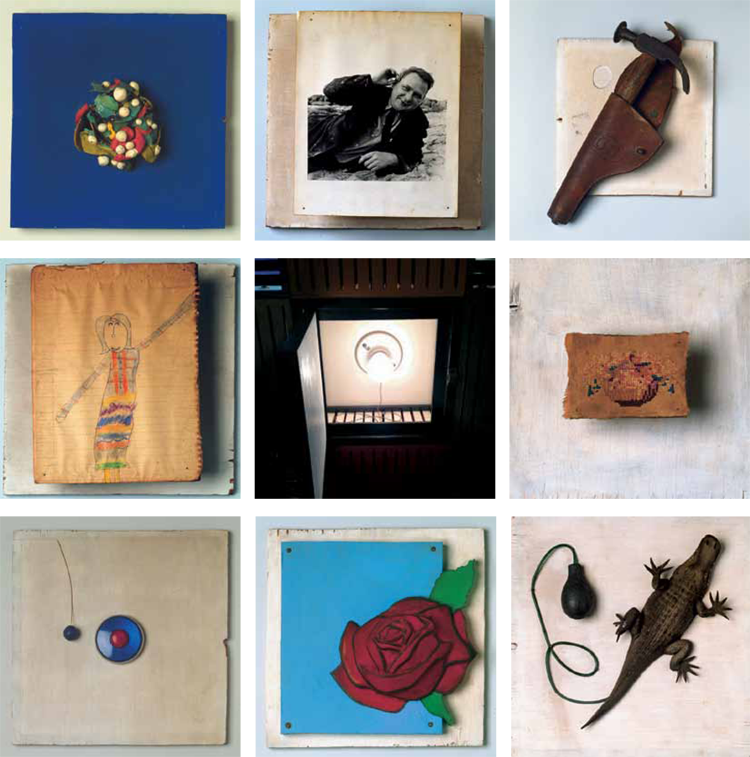

- Fig. 2: Eve Hesse, Untitled, 1967. Acrylic, wood shavings, and glue on masonite with rubber tubing. 12 x 10 x 2-1/2 inches. Yale University Art Gallery; gift of Robert Mangold, B.F.A. 1961, M.F.A. 1963, and Sylvia Mangold, B.F.A. 1961, in memory of Eva Hesse, B.F.A. 1959, and in honor of Helen A. Cooper © The Eva Hesse Estate. Courtesy Hauser & Wirth.

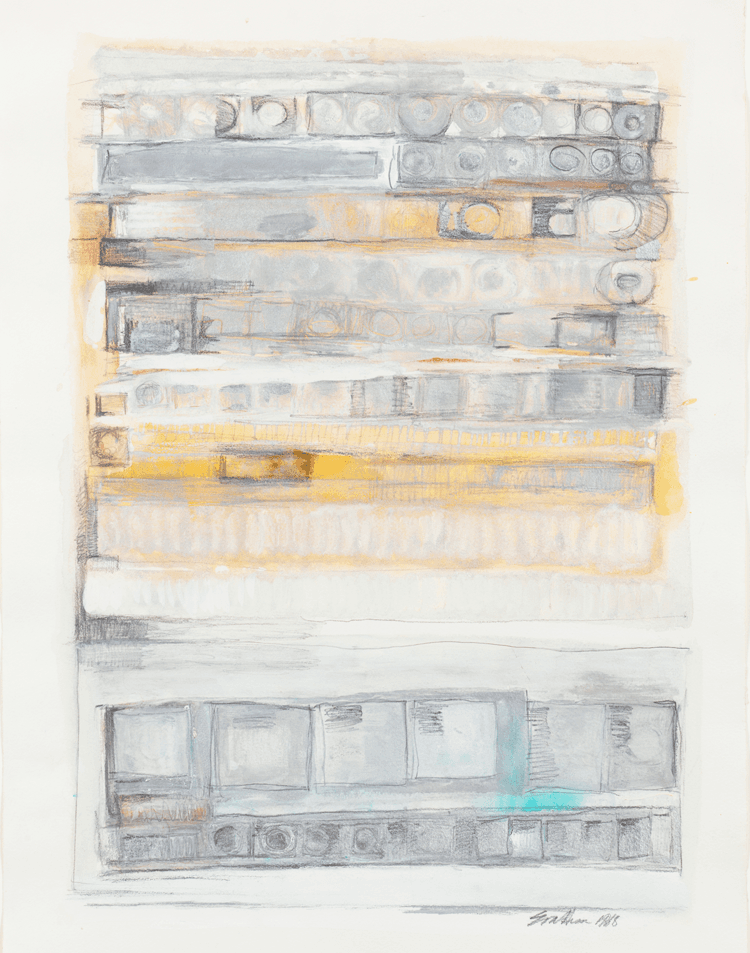

In the 1960s, however, Hesse and LeWitt forged a close bond after they became neighbors in the Bowery neighborhood of lower Manhattan. The friendship that ensued shaped their lives and their art in profound and reciprocal ways. LeWitt’s explorations of repetition and seriality, his use of graph paper as a support for his drawings, and his practice of having his sculptures professionally fabricated would all be adopted by Hesse. In turn, Hesse's sculptures, made with flexible materials such as rope, latex, string, and rubber tubes, inspired LeWitt to embrace the possibilities of art that changes each time it is displayed. This notion provided a crucial impetus for the more than 1,200 wall drawings that LeWitt produced in his long career, which vary each time they are drawn, depending on the latitude afforded to drafters by LeWitt’s instructions and the changing physical conditions of the walls upon which they are made.

Sometimes a single work of art can be the catalyst for an entire exhibition. Such is the case with Converging Lines. LeWitt’s Wall Drawing #46 (Fig. 1) inspired the idea for this exhibition. While in Paris in May 1970, LeWitt conceived the wall drawing as a tribute to Hesse in response to learning that she had passed away from a brain tumor in New York at the age of 34. Covering the entire surface of a wall with irregular (or “not straight,” as he called them) pencil lines—the first such wall drawing he ever made—he invoked the soft, pliable materials that wrap around, protrude, or dangle from so many of Hesse’s sculptures (Fig. 2). As LeWitt later explained: “I wanted to do something at the time of her death that would be a bond between us, in our work. So I took something of hers and mine and they worked together well.”

Wall Drawing # 46 was more than just a poignant gesture of affection and admiration, however. It also represented a pivotal turning point in LeWitt’s career. The not straight line became a key motif of LeWitt’s personal lexicon for the remainder of his life; he incorporated it in nearly one hundred wall drawings and countless works on paper. It also led to the development of significant bodies of later work, including his many wavy line gouaches and the Scribble drawings he made in the last years of his life (Fig. 3). LeWitt made Wall Drawing #46 in Hesse’s honor but in many ways the not straight line was arguably one of her biggest gifts to him.

Among the greatest satisfactions of curating exhibitions are the unexpected discoveries research yields along the way. The exhibition may have begun with Wall Drawing #46 as its inspiration, but it reveals many unexpected facets of their friendship as well. Here is a sampling of a few of my personal favorite findings:

• I’m always interested in the early lives and day jobs of artists. LeWitt worked as a receptionist at the Museum of Modern Art in the early 1960s, an experience that had a huge impact on his personal and artistic life. But what I didn’t realize until working on this exhibition is that in the mid-1950s, at the same time, Eva Hesse and Sol LeWitt both worked for Seventeen magazine, the first magazine in the U.S. dedicated to teenagers.

While they didn’t actually meet until later on (perhaps because LeWitt worked freelance), I made a startling and happy discovery in the Hesse Archives at Oberlin College when I examined the September 1954 issue of Seventeen magazine. In the corner of a lengthy article on Hesse—the first bit of press attention she received—an illustration of an elaborately decorated birthday cake caught my eye (Fig. 4). Beneath the illustration was a small but very familiar signature: LeWitt’s. How fitting that these two artists, who went on to become champion pen pals, met on a page before they met in person.

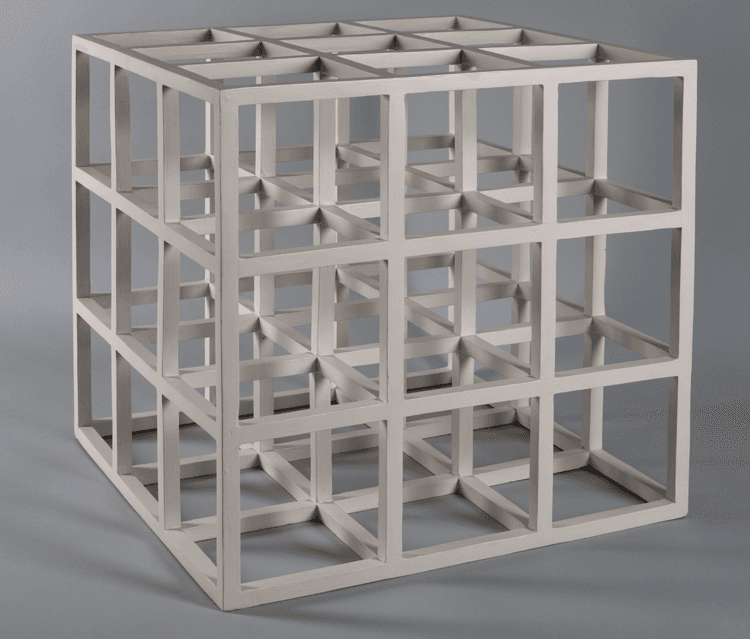

• Exhibition research always involves going down rabbit holes. This show was a full-fledged warren. The work of art I researched most extensively (translation: was obsessed by) is Nine Boxes, a colorful structure that LeWitt made in 1963 out of painted, slatted wood (Fig. 5). It is reproduced in color and discussed at length for the first time in the Converging Lines catalogue.

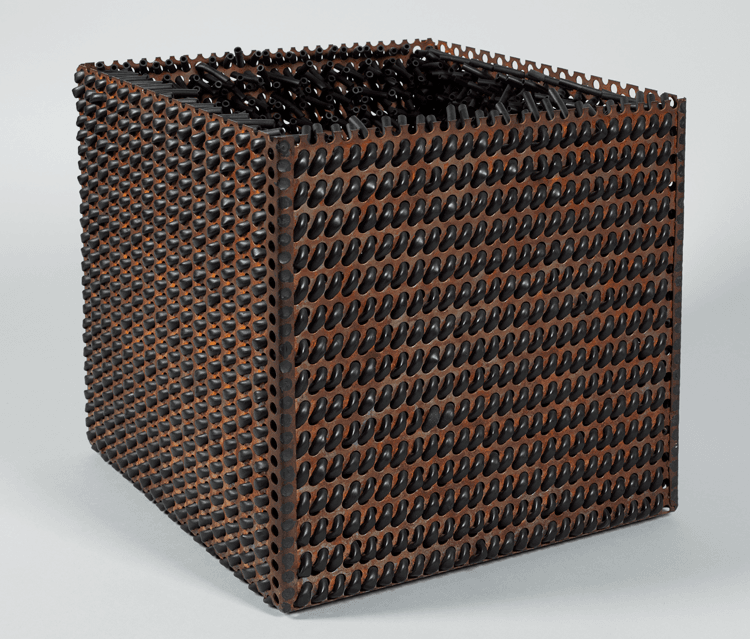

- LeWitt’s impact on Hesse’s, Accession V, a galvanized steel and rubber sculpture, responds to LeWitt in its use of the cube (a quintessential LeWittian and Minimalist form), such as his 3 x 3 x 3; the sculpture also marks one of Hesse’s first attempts at working with outside fabricators, a practice commonly used by LeWitt at the time.

I became intrigued by the work after seeing a tiny black-and-white image of it in LeWitt’s 1978 MoMA catalogue. The medium line revealed that each of the nine boxes contained a work by other artists. While I was initially disappointed to learn that Hesse was not one of the contributors, I quickly became fascinated by what it did contain. LeWitt filled the structure with miniature works of art by friends and family members and flashing bulbs that offer brief glimpses of what’s inside (Fig. 5a). Among the contents are a blue sculpture made out of Play-Doh by Robert Ryman and needlepoint bowl of fruit embroidered by LeWitt’s beloved aunt. Tom Doyle, Hesse’s husband at the time, contributed a hammer in a Civil War holster and the minimal pièce de resistance at the center of the box is a single light bulb provided by none other than Dan Flavin. In the catalogue, I connect this work not only to LeWitt’s community at the time but also to a widespread craze for boxes among artists (including Hesse) in the 1960s, and LeWitt’s interest in play and hidden forms.

• Anyone who was lucky enough to call LeWitt a friend knows that he was a first-rate correspondent. Just as his wall drawings kept art students around the world busy, the copious number of postcards and letters he wrote kept the United States Postal Service in business. Thirty-nine postcards that LeWitt sent Hesse are reproduced in the exhibition and it’s accompanying catalogue. LeWitt’s warmth and dry sense of humor really come through in the postcards he dispatched Hesse from around the globe. He sent her an image of sand dunes from Morocco, lobster traps in Maine, and a roaring hippopotamus in the Netherlands. My personal favorite is a Smithsonian Museum postcard he sent of a mummified bull (Figs. 6, 6a) that looks possessed by the devil, with the succinct, tongue-in-cheek message: “Dear Eva, I hope this doesn’t scare you.” I also love the way he opens a 1967 postcard to her, informing her that this is the second postcard he has sent her from Germany, whereas “Dan Graham has only one.”

In organizing this show, I was also struck by a few sobering realizations. LeWitt first publicly exhibited his art in a group show in New York in 1964, when he was 36-years-old. That may seem like a pretty unremarkable fact in and of itself, but it is humbling to consider this relative to the fact that Eva Hesse passed away at the age of 34. She accomplished an astonishing amount as an artist in such a short time.

Both Hesse and LeWitt helped us reconsider what art could be. As Converging Lines demonstrates, the greatness they achieved was in part due to the support and inspiration they gave one another.

—

Veronica Roberts is the curator of modern and contemporary Art, Blanton Museum of Art, University of Texas at Austin.

-.png)

,-May-19_Cover.png)

,-May-19.png)

.png)