Conversations Around American Gothic

The War took the public’s mind temporarily off art but at its end French artists were sitting on top of the world. U.S. painters, unable to sell at home or abroad, tried copying the French, turned out a profusion of spurious Matisses and Picassos, cheerfully joined the crazy parade of Cubism, Futurism, Dadaism, Surrealism. Painting became so deliberately unintelligible that it was no longer news when a picture was hung upside down.

In the U.S. opposition to such outlandish art first took root in the Midwest. A small group of native painters began to offer direct representation in place of introspective abstractions. To them what could be seen in their own land—streets, fields, shipyards, factories and those who people such places—became more important than what could be felt about far off places. From Missouri, from Kansas, from Ohio, from Iowa, came men whose work was destined to turn the tide of artistic taste in the U.S.

—“Art: U.S. Scene,” Time, December 24, 1934 [Thomas Craven]

In between the World Wars, isolationism led Grant Wood (1891–1942), John Steuart Curry (1897–1946), Thomas Hart Benton (1889-1975), and other painters to reinvent American art by examining scenes from daily life in the United States. Rejecting abstraction as too European and understandable only to cognoscenti, they promoted realism, with its revered history in early American art, as a national style—one with which they could communicate with ordinary Americans. East Coast patrons and critics catapulted them to fame, their depictions of rural and small town life tapping into a desire for something genuine and distinctively American. Although Wood, Curry, and Benton each developed his own style and ideas about what art should be and do, from 1934—the watershed moment when they appeared in the pages of Time as the great triumvirate of the new painting—the three Midwesterners were bound inextricably together.

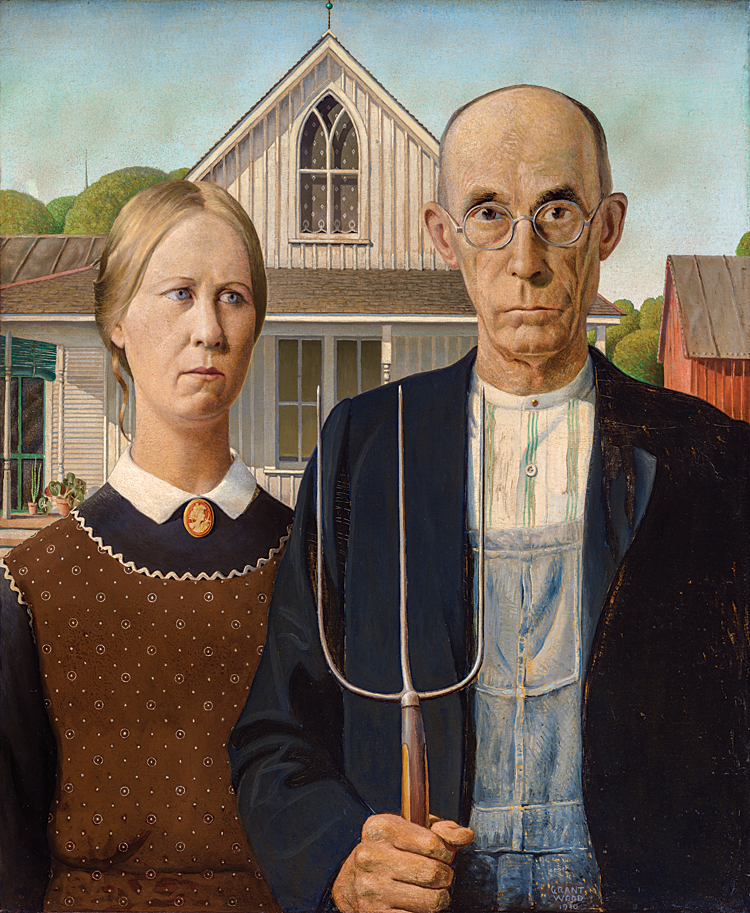

Does American Gothic celebrate America or critique it? Is it ruthless or affectionate? Does it contain religious symbolism? Who are these people and how do we read their expressions? Did Wood rely on stereotypes? Why did this modest painting become so famous, and why has its popularity been so universal and enduring? These questions and many more have intrigued viewers of Grant Wood’s picture for eighty-four years—a testimony to the artist’s ingenuity.

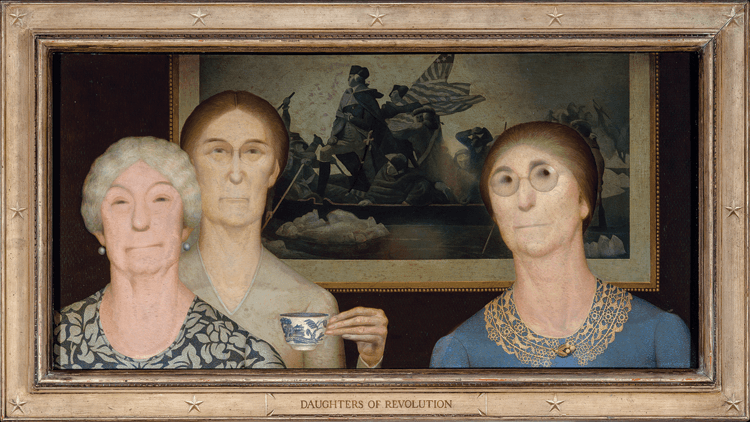

The colonial teas hosted by the Daughters of the American Revolution every year on Washington’s Birthday, and the festivities in 1932 that marked the bicentennial of the first president’s birth, inspired Wood’s clever exposé of patriotism taken to extremes. Wood designed and painted the frame with illusionistic stars and the picture’s title. He eliminated “American” from the organization’s name, both expanding the painting’s meaning beyond its specific circumstances and underscoring its ironic tone.

Curry’s double portrait of his parents evokes the homespun qualities widely associated with the American farmer. It also suggests that the virtues of rugged hard work and determination make the comforts of home possible. These included modern conveniences: the telephone and radio that made farmers who were formerly isolated part of a community. Curry’s father’s concerned expression seems to forecast the impending financial crisis that would soon destroy this fragile prosperity.

Curry saw heroism in acts of daily life, such as a father protectively ushering his family into a storm shelter as a menacing twister approaches. An outgrowth of his early work as an illustrator, Curry’s narrative painting style reveals a flair for drama and storytelling details, such as the varied reactions of the animals and the eerie atmosphere he captured in this painting. Completed just after the stock market crash, Tornado’s apocalyptic view of the world suited the national mood.

The Kansas-born Curry painted this breakthrough picture in his Connecticut studio from memories of his childhood. After a New York Times critic praised Baptism in Kansas, patron Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney offered the artist a stipend and purchased the painting for her new Whitney Museum of American Art in New York. Residents of his home state, on the other hand, viewed Curry’s work as a betrayal; to them he was an outsider who ridiculed Kansans by bringing their idiosyncrasies to light.

In Appraisal, Grant Wood exposed the absurdity of one of the common myths about rural America: that the countryside is populated with naïve bumpkins. Wood’s farm woman has a savvy look, as she negotiates the sale of a chicken to an expressionless woman from the city. The profile of the city dweller mirrors that of the bird. Wood himself appears to have identified with the farm woman, yet he took advantage of such stereotypes when fashioning his public persona: he and Curry posed for Time magazine wearing denim overalls.

The exhibition Conversations Around American Gothic marks a historic partnership between the Cincinnati Art Museum and the Art Institute of Chicago, institutions holding two of Grant Wood’s most celebrated paintings: Daughters of Revolution and American Gothic. Anchored by these two icons, this tightly focused exhibition features works selected for the stories they tell individually, collectively, and in comparison with one another. Comparisons of these paintings of the American heartland aim to stimulate conversation about stereotypes, nationalism, urban versus rural life, humor versus sincerity, shifting definitions of “realism,” and why a painting of a farmer and his daughter standing before a Gothic Revival cottage became one of the most widely recognized American paintings of all time.

To highlight Wood’s genius and intentions, the exhibition takes a close look at Daughters of Revolution, the painter’s incisive statement about the folly of excessive patriotism. Wood deemed this painting his only satire and dared not ask anyone to pose (except for the hand), for fear of offending his models. The painting evolved from a run-in with the Daughters of the American Revolution, who ignited a furor over the German manufacture of a commemorative window he had designed for the new Cedar Rapids Veterans Memorial Building. In the painting, Wood highlights in fine detail the foreign origins of all we deem “American,” including a teacup in the wildly popular Blue Willow pattern, an English design based on Chinese motifs. In the background behind the smug matrons appears one of the ubiquitous engravings after Washington Crossing the Delaware, the iconic 1851 painting created in Dusseldorf by the German-born artist Emanuel Leutze. The irony of Wood’s own enterprise—as a European-trained painter seeking to invent an American style by drawing upon the example of the Northern Renaissance masters—did not escape the artist; lessons he learned abroad supported his firm belief that the painting of local subjects and fostering of regional art centers would lead to American art of national significance.

Conversations Around American Gothic is on view at the Cincinnati Art Museum through November 16, 2014.

For more information, visit www.cincinnatiartmuseum.org or call 513.721.ARTS.

Julie Aronson is curator of American paintings, sculpture and drawings at the Cincinnati Art Museum.

This article was originally published in the Winter 2014 issue of Antiques & Fine Art magazine, a digitized version of which is available on afamag.com. InCollect.com is a division of Antiques & Fine Art, AFAnews, and AFA Publishing.