Cross Country: The Power of Place in American Art, 1915–1950

As the population of the United States shifted from rural to urban by 1920, artists forged new relationships to their national surroundings. Life in the big city, with its bustling crowds and towering skyscrapers, is widely recognized as a key influence in American modernism of the first half of the twentieth century, but artists also sought inspiration from wide open spaces and small town culture across the United States. Cross Country: The Power of Place in American Art, 1915–1950, at the High Museum of Art, Atlanta, brings together works by more than eighty artists who found inspiration beyond the city limits in the first half of the twentieth century. The show includes not only trained painters but also photographers and self-taught artists who were earning major recognition from the American art world for the first time in history.

- Fig. 1: Georgia O’Keeffe (1887–1986), Red Canna, 1919. Oil on board, 13-13/16 x 10-3/8 inches. High Museum of Art, Atlanta; Purchase with funds from the Fine Arts Collectors and the 20th-Century Art Acquisition Fund and gift of the Pollitzer Family in honor of Anita Pollitzer, to whom the artist originally gave this work (1996.18). © Georgia O’Keeffe Museum/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

The invention of the automobile and the creation of the interstate system made it possible for these artists to explore far-flung locales, but they were also encouraged to do so by grants, commissions, the lure of newly established art schools and artist colonies, and various Depression-era government agencies.

Community and Retreat

The support of like-minded friends and colleagues drew artists to informal art colonies in rural locales. One such was the community of Woodstock, in the Catskills Mountains of upstate New York. The painters Yasuo Kuniyoshi and George Ault both began spending time there in the 1930s. Whereas Kuniyoshi embraced the camaraderie of his fellow artists in the community, Woodstock offered Ault a retreat from the pressures of life. Yet examples of their work from Woodstock included in this exhibition emphasize the solitude such retreat could offer.

Not far from Woodstock, along the shores of Lake George at the base of the Adirondack Mountains, Georgia O’Keeffe and her husband, photographer and gallery owner, Alfred Stieglitz, spent long stretches of the summer months at Stieglitz’s family home there. Lake George was where O’Keeffe began to turn her attention to subjects drawn from nature, painting close-up views of flowers, such as Red Canna (Fig. 1), or landscapes, such as Lake George. Stieglitz, too, was inspired by his rural surroundings and began to create a series of abstract photographs that he called Equivalents. With this body of work, made over the course of a decade, Stieglitz demonstrated the expressive power of pure abstraction—representation free of subject matter, but capable of provoking deep emotion.

The circle of artists who gathered around O’Keeffe and Stieglitz at his New York galleries also provided a robust community for the couple. With her good friend Rebecca Salsbury (Strand) James, O’Keeffe first traveled to New Mexico, where she would ultimately settle. James also moved there, and lived among the artists, writers, and photographers who circulated around the magnetic personality of Mabel Dodge Luhan at her home in Taos, New Mexico. Work from the early 1930s by James, painted in reverse on glass, shares affinities with O’Keeffe’s images of flowers from around the same time, suggesting their close personal and artistic relationship.

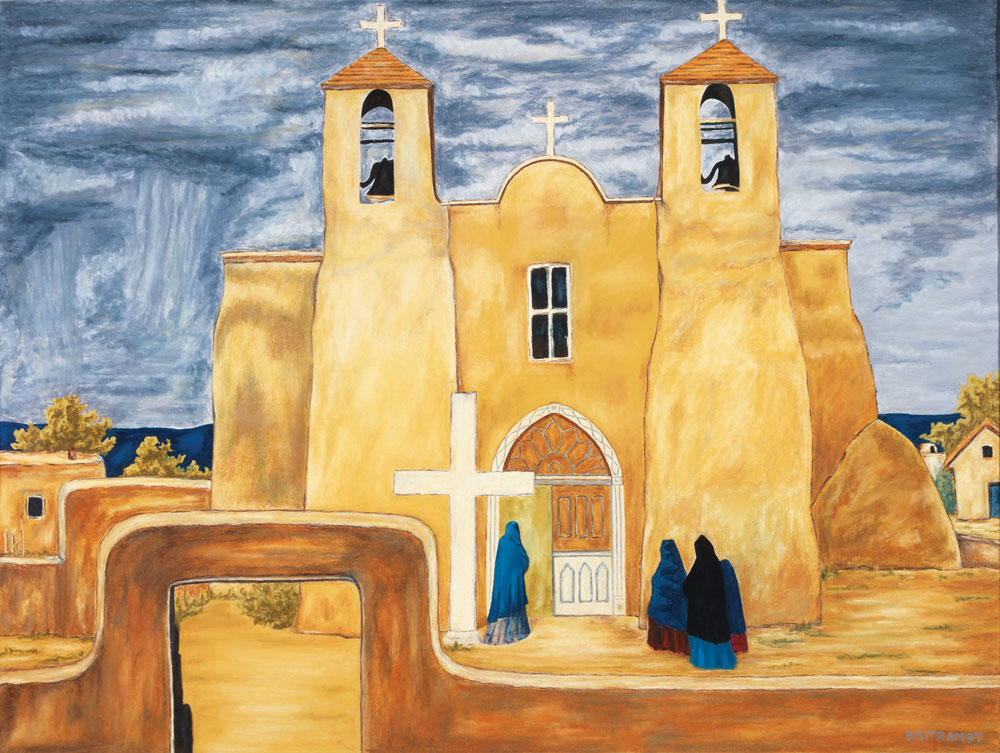

- Fig. 2: Emil Bisttram (1895–1976), Church at Ranchos II, 1937. Oil and pastel on paper, 21 x 27-3/4 inches. Private Collection, Atlanta.

Photographer Ansel Adams spent time with O’Keeffe at Taos, where they both rendered what would become one of the most pictured churches in the American Southwest, the seventeenth-century Mission Church of Saint Francis of Assisi in the village of Ranchos de Taos. Both reveled in the elegant, formal abstractions of the adobe-style architecture. Other artists also noted the church’s role in the local community. One was Emil Bisttram, who had moved to Taos from Chicago to join the active colony of artists working there. He painted several versions of the church that demonstrated the daily function of this famous modernist icon within this sleepy New Mexican village (Fig 2).

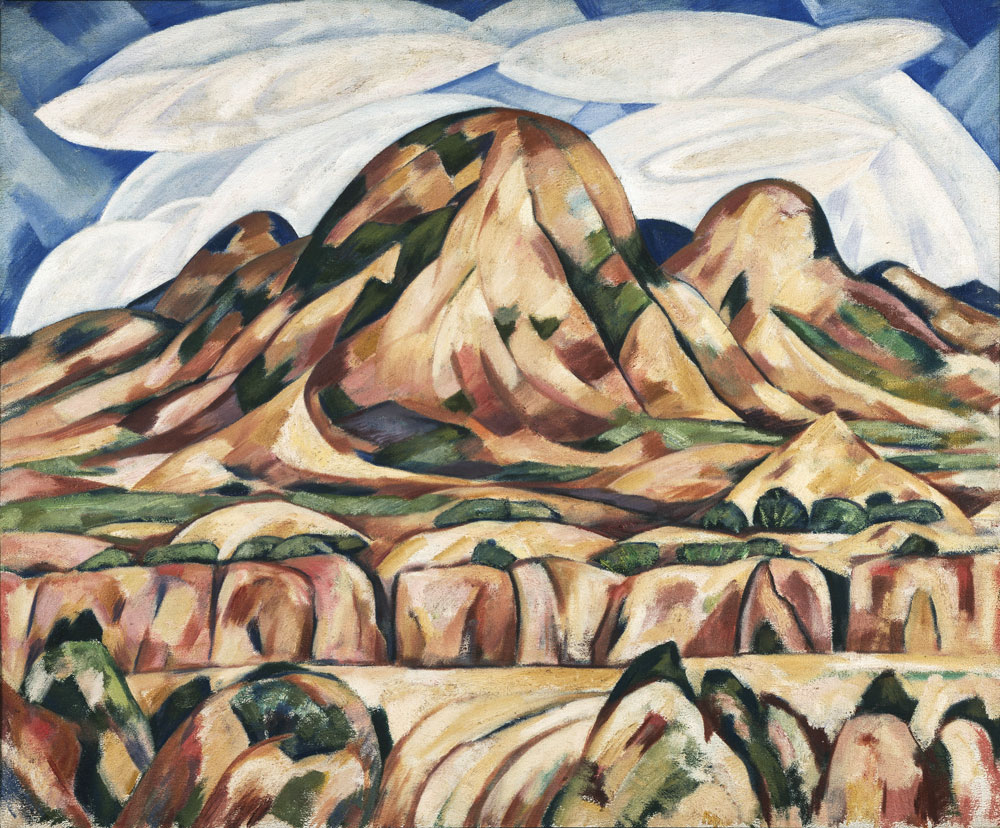

For Marsden Hartley, who travelled to the Southwest in 1918–1919, the region offered not only a break from the pressures of life in Manhattan, but also an opportunity to explore an area rich in history and culture unique to America—“an American discovering America,” as he described it. Hartley was fascinated by Native-American cultures as well as the Southwestern landscape and continued to paint scenes from memory for years after his visit there. New Mexico Landscape (1919–1920) (Fig. 3) as its date suggests, was likely painted from memory upon his return to New York.

Charles Sheeler also engaged with America’s history as a subject for many of his paintings and photographs. Along with his good friend, the artist Morton Schamberg, Sheeler moved into an historic farmhouse in the small Pennsylvania town of Doylestown in 1910, about thirty miles west of Philadelphia. The region had been settled by Germans in the eighteenth century, and many of the old fieldstone farmhouses and traditional furniture and craft began to factor into Sheeler’s work. Though he became well known for his crisp, clean-lined precisionist views of America’s most efficient and modern factories, Sheeler’s renderings of a shadowy old stairwell (Fig. 4) appears equally modern.

Not far from Doylestown, the painter and illustrator N. C. Wyeth worked from his Chadds Ford, Pennsylvania, studio with an art colony comprised of himself and his talented children, Carolyn, Henriette, and Andrew. The Wyeth family’s quiet, rural life both in Pennsylvania and in Maine, where they spent summers, encouraged an atmosphere of creative ingenuity, and by the age of twenty, the young Andrew was already receiving his first acclaim as an artist. In a pair of paintings from 1936, both titled Ridge Church, father and son take on the same subject, a country church in the small town of Glenmere near their Maine home, yet each reveals something of their unique approach.

Foundation Grants

Private organizations like the John Simon Guggenheim Memorial and Julius Rosenwald Foundations, both established in the 1920s, offered fellowships to artists that often supported cross-country travel. Many of the projects they funded engaged with an effort to redefine traditional conceptions of the United States and her people.

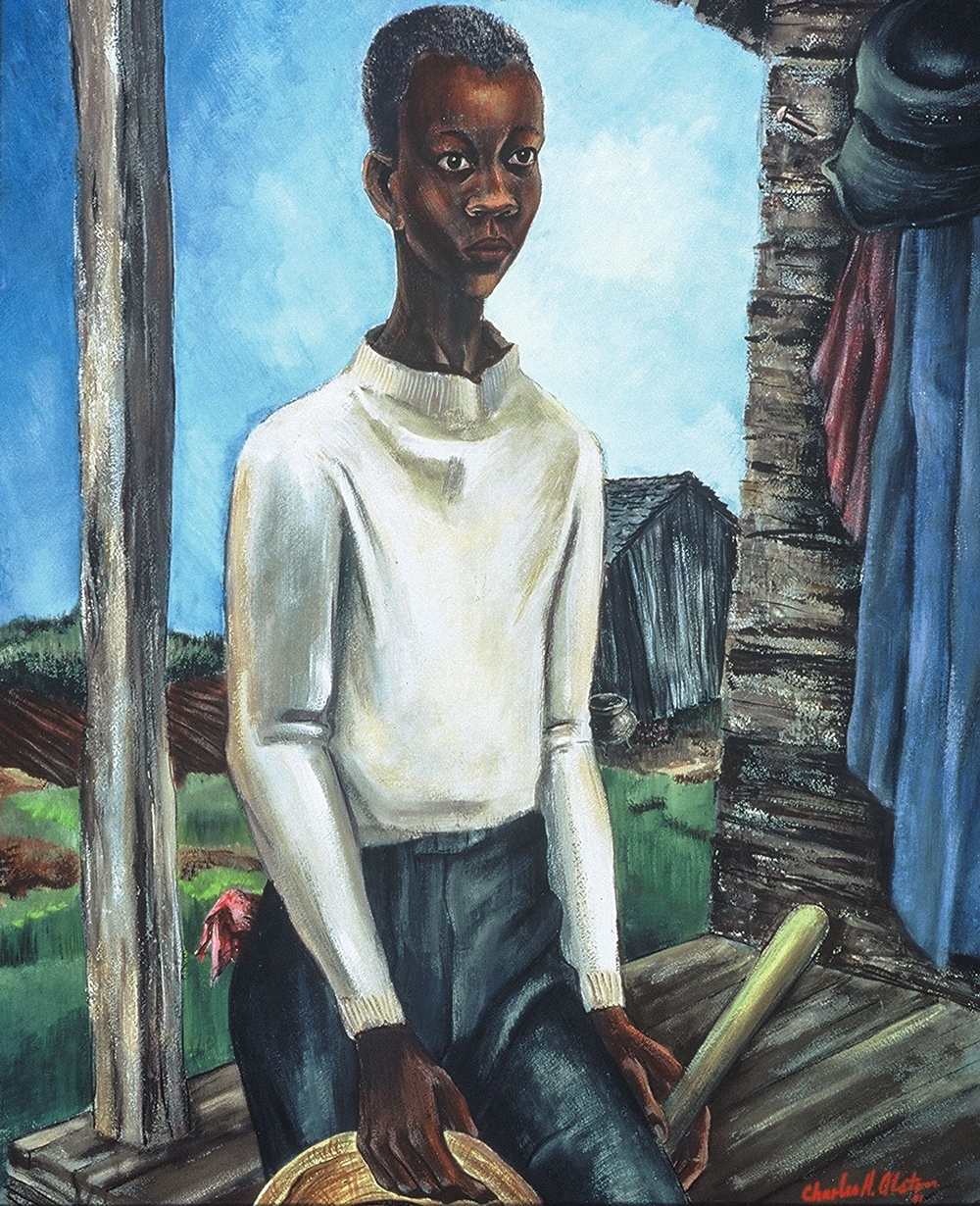

When the painter Charles Alston applied for a Rosenwald fellowship, he framed his project as an opportunity to unseat entrenched American archetypes such as the “middle western White male” epitomized by Grant Wood’s American Gothic (1930). Alston pointed out that such iconic paintings “have never been made about the Negro in the United States. Hitherto, the Negro has been treated individually and sentimentally.” 1 Using his fellowship to travel to the South in 1940, Alston challenged the “sentimental” depiction of Southern black life with works like Farm Boy (Fig. 5). The boy’s stern, faraway expression and an elongated body, which echoes the worn narrow post to his right, suggest the country’s continued reliance on black agrarian labor, even in the contemporary moment long removed from slavery that the boy represents.

- Fig. 6: Jacob Lawrence (1917–2000), Firewood #55, (from The Great Migration series), 1942. Gouache, ink, and watercolor on paper, 22-3/4 x 31 inches. Smithsonian American Art Museum, transfer from the U.S. Information Agency through the General Services Administration © Jacob Lawrence / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

The Rosenwald Foundation was broadly dedicated to advancing opportunities for African Americans in the United States, and its awardees included educators, scientists, and visual arts practitioners regardless of their skin color. As a “crucible of black culture,” the South also attracted white artists like Robert Gwathmey and Lamar Baker, who received Rosenwald grants to travel there in the 1940s.

Perhaps the most famous artistic project funded by a Rosenwald fellowship is The Great Migration (Fig. 6), Jacob Lawrence’s visual epic of how millions of African Americans left the South in the post-Reconstruction era. Lawrence did research for the series at New York’s Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, not far from his home base of Harlem. In fact, until he traveled to the South later in 1941, gathering inspiration for subsequent works, Lawrence’s only experience of the South was imagined, or in his own estimation, felt. “If you weren’t born in the South, your parents were. Your life had a whole Southern flavor; it wasn’t an alien experience to you even if you had never been there,” he said.2

After his service in the National Guard during World War II, Lawrence went on to receive an award from the John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Foundation. The Guggenheim Foundation’s mission was much broader than the Rosenwald’s, and in 1937, Edward Weston became the first photographer to receive a Guggenheim fellowship. Untethered from the need to earn his livelihood through studio portraiture, Weston travelled the American West, generating some 1,400 negatives over 20,000 miles. “I accomplished more than I would have in ten years under ordinary circumstances,” he said.3

Government Funding and Populist Aesthetics

It was another organization, the Farm Services Administration (FSA), that catalyzed the most iconic photographs of the period. The FSA was a New Deal agency that employed dozens of photographers between 1935 and 1945 to document the success of the government’s efforts to resettle displaced farmers and humanize the suffering of millions during the Great Depression. Dorothea Lange traveled through more than twenty states taking thousands of pictures for the FSA, including her portrait Florence Owens Thompson, Human Erosion in California (Migrant Mother) (1936), a work whose deep sadness and humanity resonated with millions of Americans.

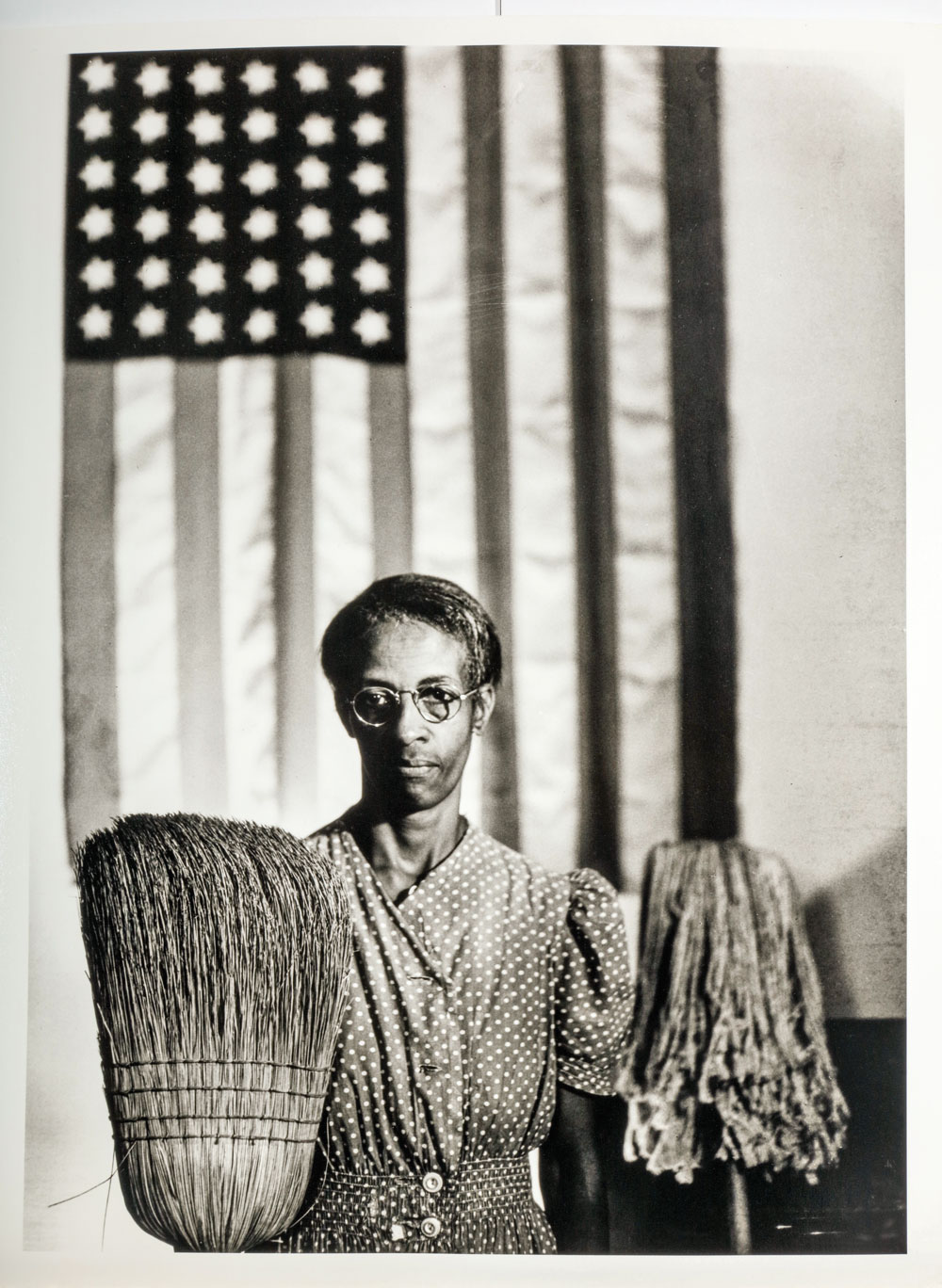

Another iconic image to emerge from an FSA assignment is Gordon Parks’ Ella Watson, American Gothic, Washington, D.C. (1942) (Fig. 7). Parks was from Chicago and the extreme segregation he experienced below the Mason Dixon line fuelled such work. Like Alston’s approach to his African American subject in Farm Boy, Parks’ portrayal of Mrs. Watson was unsentimental and, as its title suggests, a direct response to the national mythology around whiteness embodied by Grant Wood’s American Gothic.

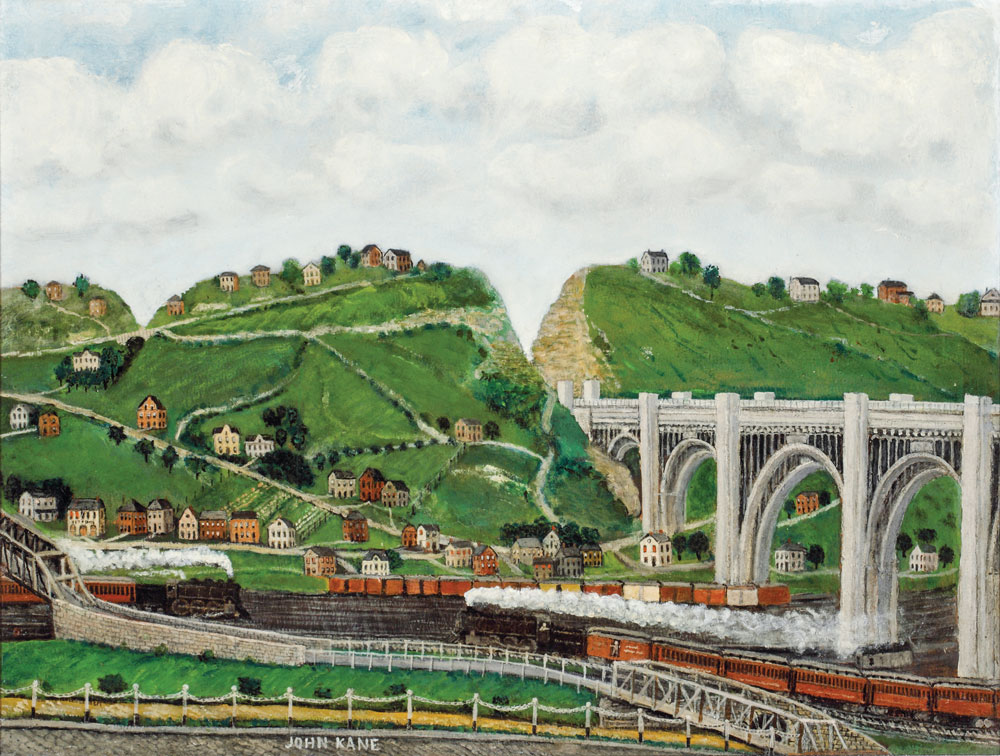

Also employed as a photographer by the FSA, Ben Shahn traveled extensively through the South and Midwest capturing everyday life on film that he would often adapt to other media. In Farmers (1943), Shahn revisits a moment he observed during the public auction of a farm, as three farmers inspect a piece of old equipment and worry over the fate of their own enterprises. Shahn was also among the thousands of artists paid by the government to create murals, easel paintings, and sculpture through the New Deal-funded Federal Art Project. The FAP’s approach to the artist as a “cultural worker” contributed to what art historian A. Joan Saab has called a “desacralization of culture” in the 1930s.4 In other words, there was a shift away from the concept of the artist as a rarefied being toward a more populist ideal of the artist. This trend dovetailed with an enthusiasm for the work of untrained artists, both historical folk artists and living self-taught artists, which gained momentum after 1927, when John Kane was included in the Carnegie International. Kane, a Scottish-American immigrant who was then working as a housepainter in Pittsburgh, created lushly detailed paintings of the heavily industrialized city’s raucous landscape (Fig. 8).

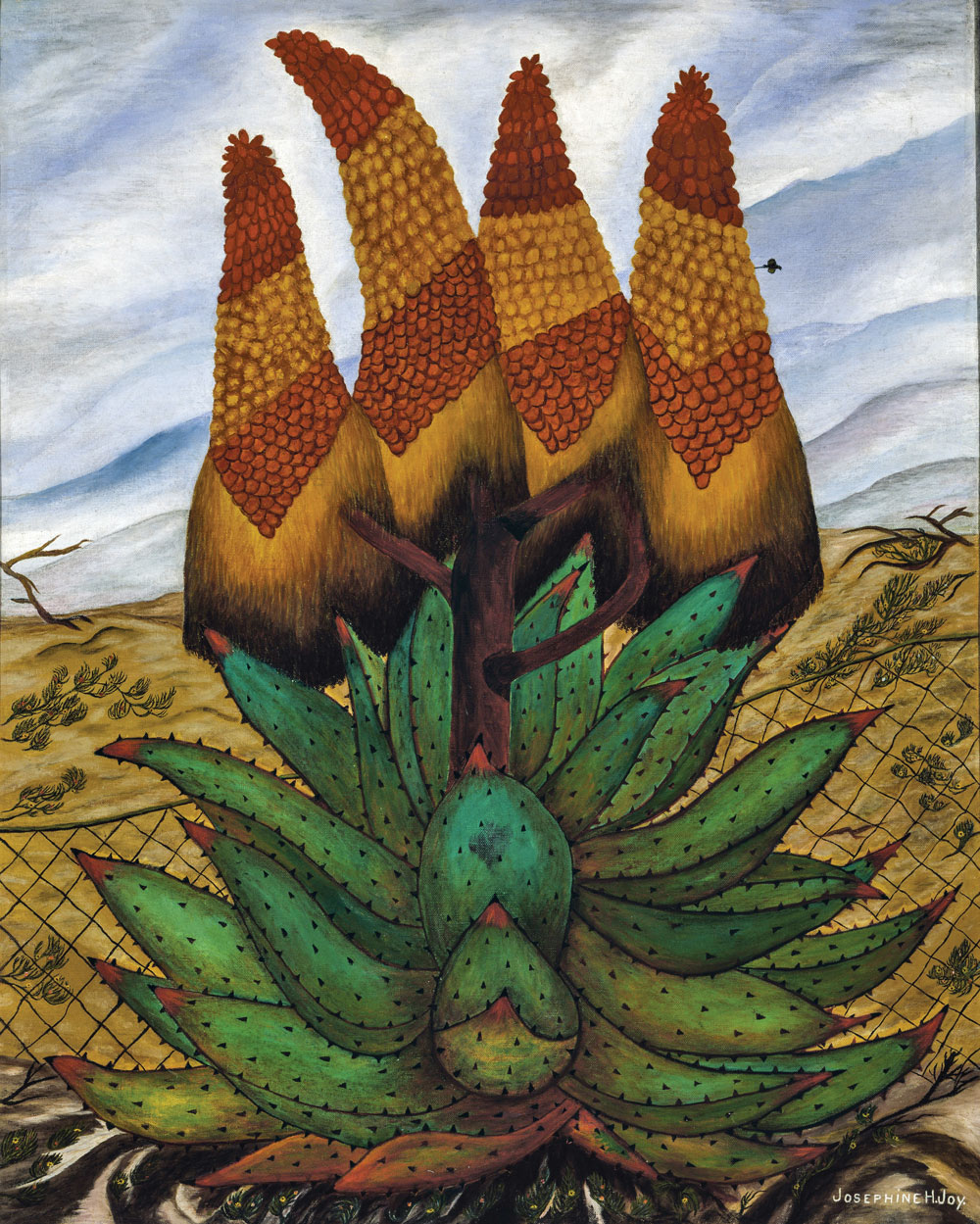

A decade after Kane’s debut at the Carnegie, MoMA presented a solo exhibition for the Nashville sculptor William Edmondson, who turned the detritus of his gentrifying neighborhood first into tombstones for his African-American community, and later into sculptures such as Nurse (1930s) (Fig. 9). Edmondson exhibited his sculpture in his yard, creating a menagerie that by 1940 was a pilgrimage site for photographers like Edward Weston. Edmondson was one of at least half a dozen self-taught artists employed by the FAP in the late 1930s and early 1940s. Others included Josephine Joy, who painted hundreds of works for the FAP, like Aloes (1935–1938) (Fig. 10), a work whose flattened perspective and vibrant palette exemplify how self-taught artists anticipated formal trends in modernism such as direct carving, skewed perspective, and expressive color, one reason for the popularity of self-taught artists at this time. Another was how they represented the “common man,” a potent identification in an era that, as many of the works in the exhibit show, saw a broadening of the people, places, and things that represented the United States.

Cross Country: The Power of Place in American Art, 1915–1950 is on view from February 12 through May 7, 2017, at the High Museum of Art, Atlanta. An expansion of the Brandywine River Museum of Art’s Rural Modern: American Art Beyond the City, Cross Country presents more than two hundred artworks, including more than seventy from the High’s permanent collection. For more information call 404.733.4400 or visit www.high.org.

-----

Stephanie Mayer Heydt is the Margaret and Terry Stent Curator of American Art, and Katherine Jentleson is the Merrie and Dan Boone Curator of Folk and Self-Taught Art, at the High Museum of Art, Atlanta.

This article was originally published in the 17th Anniversary issue of Antiques & Fine Art magazine, a fully digitized version of which is on afamag.com. AFA is affiliated with Incollect.

2. Smithsonian American Art Museum, “Web Text for Bar and Grill, 1941, by Jacob Lawrence,” accessed November 7, 2016, http://americanart.si.edu/collections/search/artwork/?id=79031.

3. Edward Weston, “Photographing California,” Camera Craft 46, February 1939, no. 2, p. 46.

4. A. Joan Saab, For the Millions: American Art and Culture Between the Wars (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2009), 17.