Diversity in a Small Arena: The Contemporary Craft Gallery at the Newark Museum

The Contemporary Craft Gallery at the Newark Museum opened in 1989 as part of the award-winning renovation of the museum complex under architect Michael Graves. The first museum gallery in New Jersey dedicated to the display of modern and contemporary craft, it is not a large space, and, because one must pass through it to get to the north wing elevator, it is commonly referred to as the “elevator gallery.” Since it gets more traffic than almost anyplace else in the museum, it’s a perfect spot for some focused looking.

For my final installation in the Contemporary Craft Gallery before my retirement, I wanted to underscore the diversity of our collections with a survey of the works brought in over the course of my thirty-seven-year career at Newark. Landmark holdings in American craft include masterworks by Native American artists and African-American artists, as well as works by New Jersey’s best-known studio craftspeople such as Ubaldo Vitali and Paul Stankard. The fact that some of these objects, acquired as contemporary, are now seen as “historical,” makes me smile, as I, too, prepare to become a part of history. The installation is on long-term view.

|  | |

| Christine Nofchissey McHorse (b. 1948), (Hopi/Taos) Burgeon, 2015 Coiled micaceous clay, H. 18, L. 10½, W. 10 in. Purchase 2015 Helen McMahon Brady Cutting Fund (2015.15) | Virgil Ortiz (b. 1969), (Cochiti) vessel, 2015 Coiled and painted earthenware, 13 x 11 in. Purchase 2016 Charles W. Engelhard Bequest Fund (2016.25) |

In a corner of the gallery, in separate cases, two works by Southwestern native artists hold a quiet dialogue. Christine Nofchissey McHorse’s Burgeon, brooding and organic, offers an aesthetic counterpoint to Virgil Ortiz’s untitled painted vessel. The conversation is both about the differences between the artists’ Hopi/Taos and Cochiti ceramic traditions and about the role of contemporary Native American potters in the larger world of contemporary ceramics. Newark was purchasing Pueblo pottery as modern pottery before World War I, and presenting it alongside art pottery made in places like Marblehead and Rookwood.

|

| Preston Singletary (b. 1963) Tlingit chest, 2015 Cast and carved glass, H. 19, L. 31, W. 24 in. Purchase 2015 Contemporary Art Society of Great Britain Fund and Mr. and Mrs. William V. Griffin Fund (2015.10 a,b). |

At the entrance to the gallery is a large Tlingit chest of carved glass by Seattle artist Preston Singletary. Newark has been buying modern glass since 1912 and buying Native American craft as modern art since the same year. Singletary’s work is inspired by designs from his Northwest Coast decorative heritage, an example of which is the eighteenth-century carved and painted Tlingit chest in the adjacent gallery: Two different but closely linked expressions of artistic impulse.

|

| Peter Voulkos (1924–2002) plate, 1981 Thrown and altered stoneware, Diam. 22, H. 5 in. Purchase 2002 Membership Endowment Fund, Mrs. James C. Brady Bequest Fund, Charles W. Engelhard Bequest Fund and Dr. and Mrs. Earl LeRoy Wood Fund (2002.23.4). |

That same artistic parallel can be drawn between the art pottery on display within sight of the Contemporary Craft Gallery, and the massive scarred and pummeled plate by Peter Voulkos that hangs on the gallery wall. A revolutionary ceramicist, Voulkos exaggerated forms, replacing functional limitations with a sculptural freedom of expression. I don’t venerate Voulkos as a sculptor; I admire him as a potter. The fact that Voulkos’ pots can be appreciated as art is fine by me. It is his ability to manipulate clay into something powerful and new that touches me. His plate is both sculpture and drawing, in much the same way that the art pottery vases displayed down the hall were seen as both sculptural and painterly a century ago. The desire to be seen as art is not new.

|  | |

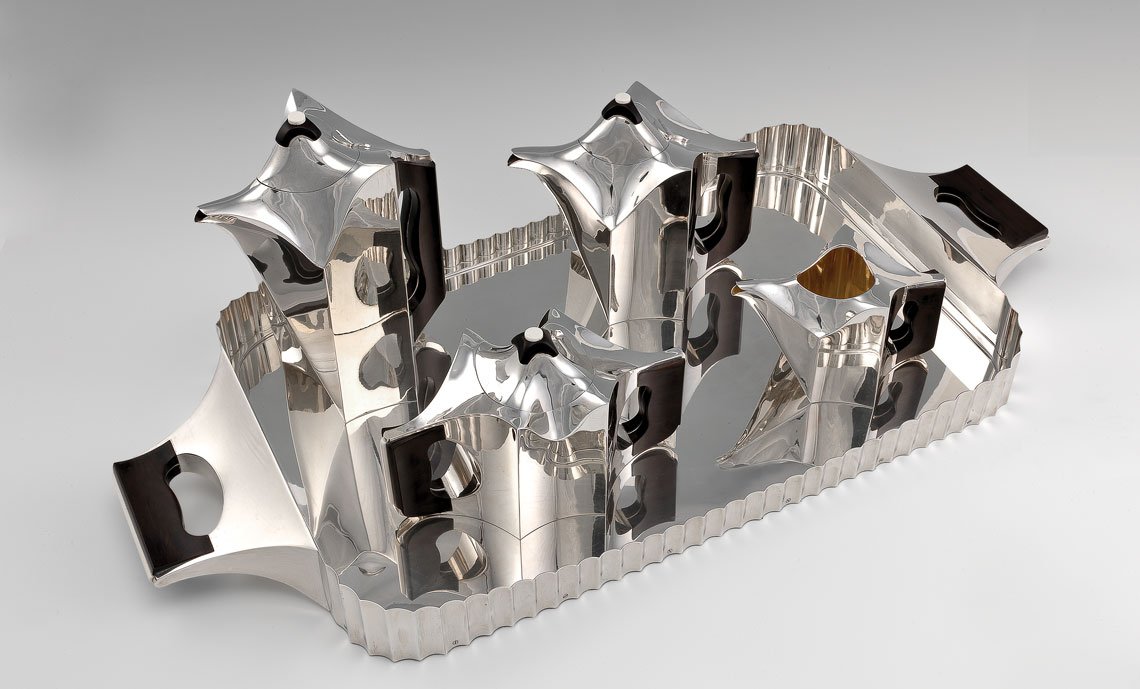

| Ubaldo Vitali, (b. 1944) Anniversary Service, 1984 Silver, ebony, ivory, plastic (tray is 33½ x 15 inches) Purchase 1984 The Members’ Fund (84.1a-f) Photo by Gene Young | Michael Puryear (b. 1944) Arch coffee table, 2007 Bleached and stained ash, H. 15½, L. 48½, W. 27½ in. Purchase 2007 Friends of Decorative Arts (2007.30.2) |

In another corner is the resplendent silver tea and coffee service commissioned from Ubaldo Vitali in 1983 to commemorate the museum’s seventy-fifth anniversary in 1984. It sits on the perfect base for it: the Arch coffee table, by Michael Puryear, made for the gallery, acquired in 2007, and now displayed for the first time. I decided to acquire something by Michael in 2006, when sitting next to him at the American Craft Council’s annual conference in Houston. Michael’s brother, sculptor Martin Puryear, was on stage as the keynote speaker. Newark had just purchased an amazing sculpture by Martin, and the irony that it was he and not Michael on stage speaking to a roomful of craftspeople and curators was not lost on me. Together, Ubaldo’s silver service and Michael’s table share an important message: function does not negate art. If there is one lesson I take away from my decades at the Newark Museum, that’s one I value most.

Ulysses Grant Dietz is chief curator and curator of decorative arts, Newark Museum, Newark, N.J. He retires as of December 31, 2017.

This article was originally published in the Winter 2017 issue of Antiques & Fine Art, a fully digitized edition of which is available at www.afamag.com. AFA is affiliated with Incollect.