Drawn With Spirit: Pennsylvania German Fraktur

from the Joan and Victor Johnson Collection

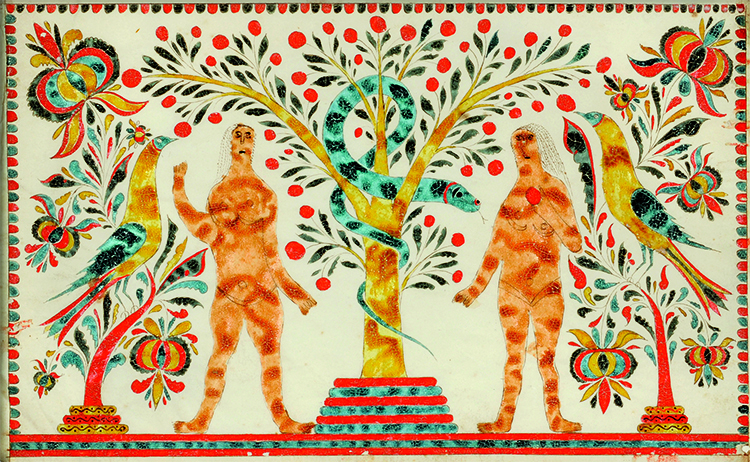

- Fig. 1: Drawing of Adam and Eve, attributed to the Sussel-Washington Artist (active 1760–1785), probably Lancaster County, Penn., ca. 1775.

Watercolor and ink on laid paper, 7¾ x 6½ inches.

This drawing of Adam and Eve (formerly owned by fraktur scholar and collector Donald A. Shelley) is inscribed (translation): “Adam in Paradise. A blind man is a poor man who cannot control his wife. Poor man./Eva the mother. A pious wife is the part of life that man finds but seldom.”

Fraktur—decorated Germanic manuscripts and printed documents—have long been admired as an extraordinarily vibrant and creative art form (Fig. 1). A European tradition brought to America by German-speaking immigrants, who began settling in southeastern Pennsylvania in 1683, fraktur are among the most distinctive and iconic forms of American folk art. The Philadelphia Museum of Art was one of the first major institutions to collect Pennsylvania German fraktur and decorative arts. In 1897, then-curator Edwin Atlee Barber acquired the museum’s first fraktur and, in 1929, the museum opened to the public the first period rooms of Pennsylvania German art. Many of the furnishings were donated by J. Stogdell Stokes, with additional furniture, ironwork, textiles, redware, and other objects acquired from Titus C. Geesey. The museum’s fraktur were never on par with the rest of the collection, but with the recent promised gift of nearly 250 fraktur from the collection of Joan and Victor Johnson (Fig. 2), the museum’s fraktur collection is now one of the finest in the country.

The Johnsons, Philadelphia natives, began collecting fraktur nearly sixty years ago, initially to help fill the walls of a historic farmhouse they bought and restored after their marriage in 1955. Joan, who studied contemporary art at Goucher College, loved the Bauhaus and planned to collect accordingly—but Victor, who worked in the computer industry, didn’t want to live with modern art. When Joan began antiquing with friends in nearby Bucks County, Pennsylvania, she soon became fond of folk art and, increasingly, fraktur.

At the time, fraktur were inexpensive (today, the record price paid at auction for a fraktur stands at $394,000, set in 2004 at Freeman’s Auctions in Philadelphia). Joan began to hone her eye by studying the fraktur collection at the Free Library of Philadelphia, where more than 1,300 examples are housed in the rare books department. Says Joan, “Originally I just bought anything I liked, and then as I became more knowledgeable, I decided it would be fun to have some from Lancaster County, York County, wherever, and the collection just grew from there…”

In 1965, the Johnsons moved to a sprawling Colonial Revival farmhouse, “Hidden Glen,” designed by architect G. Edwin Brumbaugh, and located in Meadowbrook, north of Philadelphia, where they resided for forty years.1 Now living in center-city Philadelphia, in a modern apartment overlooking Washington Square Park, the Johnsons’ collection was reinstalled in spaces that recreate the look of their farmhouse. In the hallway, a painting by Edward Hicks of the David Twining farmstead hangs over a chest of drawers from the Mahantongo Valley of central Pennsylvania (Fig. 3). To the right, a portrait painted by J. B. Myers, who worked in the Hudson River Valley, hangs above a painted desk made in a German-speaking community of Nova Scotia. Other furnishings are more formal, including the set of four rush seat chairs—attributed to William Savery (1721/22–1787) of Philadelphia—which encircle a gate-leg table (Fig. 4). Through the door to the living room, a desk-and-bookcase is visible. The double-dome top is one of only two known examples of this form to have line-and-berry inlay, a style of decoration associated primarily with Chester County, Pennsylvania. In the den, a dense array of eye-popping fraktur occupies the walls above and to the left of a Windsor settee (Fig. 5). The installations are arranged by Joan, who established her own interior design business—Joan Johnson Interiors—in 1970 and chaired the loan exhibition of the Philadelphia Antiques Show from 1976 to 2012. The group of fraktur in the den is identical to its arrangement in Hidden Glen, of which Joan was particularly fond; the other groupings were rearranged by Joan to suit the new location. Says Joan, “Since the fraktur are small and our walls large, I have enjoyed playing with the arrangements [in both homes]. For me, that has been as much fun as collecting.”

In the dining room, a group of fraktur united by the predominance of bird motifs hangs above a painted chest made in 1797 for Johan Griesmer of Berks County (Fig. 6). For the wall above the headboard of a spectacular painted bedstead in her bedroom, Joan selected a group of fraktur depicting the story of Adam and Eve (Fig. 7). Other groupings have no particular theme other than a pleasing visual combination.

Since their collection’s humble beginnings as something colorful to fill the empty walls of a small farmhouse, the Johnsons have built one of the largest and finest private collections of fraktur in existence. With nearly 250 examples, the collection has major chronological and regional breadth—covering a span of more than a century (from about 1750 to 1875 or so), with pieces from Pennsylvania as well as New Jersey, New York, Ohio, Virginia, and Canada. It also has significant depth, with multiple works by many of the most sought-after fraktur artists—such as Johann Adam Eyer, Samuel Gottschall, Andreas Kolb, Friedrich Krebs, Henrich Otto, Durs Rudy, Johannes Ernst Spangenberg, and the Sussel-Washington Artist—enabling a more nuanced understanding to emerge of how artists took inspiration from one another and how designs were transferred to new locations. In describing their promised gift, Victor Johnson notes that “these works will give people who visit the museum insight into a type of art that isn’t currently represented in depth in its collections.” Adds Joan: “I think that when these pieces are finally hung at the museum, the public will see what an interesting, intelligent, creative group of people the Pennsylvania Germans were…People of German descent are still everywhere in the greater Philadelphia area, and I think they’ll relate to the collection and be proud of their heritage.” The promised gift of the Johnsons’ fraktur collection to the Philadelphia Museum of Art is an incredible legacy from which we will all benefit greatly now and in the years to come.

To celebrate the Johnsons’ promised gift, many of their fraktur will be shown, with a variety of Pennsylvania German decorative arts, including painted furniture, redware pottery, and metalwork, in a major exhibition, Drawn with Spirit: Pennsylvania German Fraktur from the Joan and Victor Johnson Collection, at the Philadelphia Museum of Art from February 1 to April 26, 2015. Two additional, related exhibitions are also on view in the Delaware Valley: A Colorful Folk: Pennsylvania Germans & the Art of Everyday Life, at Winterthur Museum from March 1, 2015 to January 3, 2016; and Quill & Brush: Pennsylvania German Fraktur and Material Culture, at the Free Library of Philadelphia from March 2 to July 17, 2015.

A catalogue of the entire Johnson collection was recently published by the Philadelphia Museum of Art (Yale University Press, 2015). The most comprehensive study of fraktur since the 1961 publication of Donald A. Shelley’s The Fraktur-Writings or Illuminated Manuscripts of the Pennsylvania Germans, the catalogue includes an interview about the collection with Joan and Victor Johnson; an introductory essay that sets the collection in context and highlights major new discoveries; 242 large color plates; and a checklist with detailed catalogue entries and complete translations of each piece.

FRAKTUR

From the earliest known examples that were brought to Pennsylvania by German-speaking immigrants to its evolution over time into a popular icon of American folk art, fraktur has captivated hearts and minds for generations. Known in German as Fraktur, the word is derived from the Latin fractura (breaking), a reference to the broken or fractured style of lettering. The Anglicized term “fraktur” can, technically, refer to any document written or printed in Fraktur lettering, with or without decoration. It was produced in German-speaking areas of Europe from the beginning of the 1500s until the Second World War. The most common type of fraktur made by the Pennsylvania Germans was the Geburts-und-Taufschein, or birth and baptismal certificate. Whether handwritten or printed, these documents typically include extensive genealogical data (child’s name, parents’ names, location and date of birth and baptism, and godparents’ or baptismal sponsors’ names), in addition to decorative motifs such as hearts, flowers, angels, and birds. Their popularity reflects the importance of baptism within the Lutheran and Reformed Church, to which approximately 90 percent of Pennsylvania Germans belonged. Other common types of fraktur made by the Pennsylvania Germans include birth records (used by Anabaptist groups such as the Amish and Mennonites, who did not practice infant baptism), Vorschriften (writing samples), Haus Segen (house blessings), valentines or Liebesbriefe (love letters), New Year’s greetings, religious texts, family records, bookplates, and rewards of merit. Less common were marriage certificates and death memorials.

The Johnson collection includes five fraktur by the so-called Sussel-Washington Artist, whose real name is unknown, but the text and imagery on his fraktur indicate that he was a German immigrant. The striking rendering of Adam and Eve (see fig. 1) shows characteristic features of his work, such as their elliptical eyes, rosy cheeks, and the crosshatching used to conceal their nakedness; here, the crosshatching is used to embellish the fanciful dress worn by the woman riding sidesaddle. Her elaborate outfit is ornamented with a large hat and enormous ruffles at the cuffs of her elbow-length sleeves.

In the late 1700s, some Pennsylvania German families began to migrate to Ontario, Canada, in search of new land. Between 1786 and 1802, at least thirty-three families (most of them Mennonite) moved from Bucks County, Pennsylvania, to an area of the Niagara Peninsula along the Twenty Mile Creek that is now part of Lincoln County, Ontario; in the early 1800s, a number of Lancaster County Mennonites moved to Markham Township, York County; and yet other Mennonite families from Bucks, Montgomery, and Lancaster counties moved to Waterloo County. Many took Pennsylvania-made fraktur with them, which helped establish a vibrant tradition of Canadian fraktur such as this drawing made in 1829 for Catarina Meyer. The large peacocks are particularly reminiscent of those drawn by Johann Adam Eyer on some of his Bucks County fraktur.

This extraordinary drawing of a baptismal scene bears the initials “dR” for Durs Rudy, either Senior or Junior. Theodore or “Durs” Rudy Sr. immigrated with his family in 1803 and settled initially in the Skippack area of Montgomery County. By 1809, the Rudy family had relocated to the Upper Saucon region, now part of Lehigh County. Both Rudy Sr. and his son Durs Rudy Jr. are thought to have taught school and made fraktur; the work of each is at present indistinguishable from one another. The Rudys also made drawings of Adam and Eve, the Crucifixion, the Prodigal Son; birth and baptismal certificates; and metamorphosis booklets (so-called because each booklet can transform into three different scenes by raising or lowering a flap).2

Long known as the Easton Bible Artist because of a bookplate he made for the First Reformed Church in Easton, Pennsylvania, Johannes Ernst Spangenberg was one of the most accomplished fraktur artists working in the Lehigh–Northampton County region. The birth and baptismal certificate for Anna Maria Oberle (b. September 19, 1798) is one of the finest known and best-preserved examples of his work. Its large, full-sheet format enabled Spangenberg to fill the page with birds, flowers, and twelve human figures. Four lively musicians appear among the flowers at the top; at the bottom three couples are dancing, and another couple, the man smoking a pipe, surveys the scene while seated on klismos chairs that have faces on the crest rails. The certificate descended directly in the family until it was acquired by the Johnsons in 2005.

The Johnson collection is particularly rich in fraktur made by the Schwenkfelders, a German-speaking religious sect who settled primarily in what would later become Montgomery County, Pennsylvania. Strong proponents of education, the Schwenkfelders established schools that were open to children of any faith. The curriculum included arithmetic, reading, writing, grammar, and moral instruction, but not religious doctrine. Numerous Schwenkfelder schoolmasters, some of whom were also ministers, made fraktur for their students and family members. The rich color palette and dense foliate borders of this example are typical of fraktur made by David Kriebel, a farmer and Schwenkfelder minister. It is inscribed (translation): “Flowers are not all red. All men hasten toward death. Man cannot remain here, so direct your heart upward, 1802.”

Some of the most spectacular Pennsylvania German fraktur were produced well into the 1800s. Samuel Gottschall, a Mennonite schoolmaster and fraktur artist, taught during the 1830s in a schoolhouse built on land owned by his family in Franconia Township, Montgomery County. His dated fraktur were made between 1833 and 1836; most are dated 1834 or 1835. Samuel’s father, Jacob Gottschall, and brother Martin were also fraktur artists. This incredibly bold and colorful drawing of Adam and Eve is one of his masterpieces; one other example is known but lacks the birds and the Tree of Knowledge with its delightful blue snake. The heavily pooled areas of pigment and the crystalline appearance, likely caused by the use of a thick gum-arabic binder, are typical of Samuel Gottschall’s work. The original owner of this stunning fraktur is unknown, but by the early twentieth century it was owned by the Hagey family of Souderton, Pennsylvania, in which it may have descended. In 1974, this fraktur was shown in The Flowering of American Folk Art exhibition at the Whitney Museum of American Art, New York. It was acquired by the Johnsons in 1981.

Christian Ernst Beschler, who emigrated from Germany in 1764, first settled in Bucks County, where he worked as a schoolmaster. By the 1790s, he had moved to the Mahantongo Valley of central Pennsylvania, where he lived in Upper Mahanoy Township. The reddish-orange, yellow, and black palette of this certificate is typical of his work, as are the toothy unicorns and the clusters of grapes that the parrots and unicorns are eating. Made for Jacob Redinger (b. May 30, 1813), it is inscribed “gemacht von C B” (made by C B), which helped identify Beschler as the artist (previously known as the Sussel-Unicorn Artist).3

Made for Ana Maria Haberak (b. October 23, 1816), this certificate is signed by William Otto—one of four sons of Henrich Otto who followed in their father’s footsteps and became fraktur artists. In the early 1800s, William moved to the Hegins Valley in northern Schuylkill County, where he worked as a farmer, carpenter, and cabinetmaker who made painted furniture as well as fraktur for family members, friends, and neighbors. This certificate includes such typical motifs as women in striped dresses and pinwheel-shaped flowers; William signed and dated it in 1834, some eighteen years after Ana Maria was born.

Boldly drawn and colorfully executed, this fraktur includes motifs that relate to the work of both Andreas Kolb and Johann Adam Eyer. The face at the top peering through the petals above a heart is derived from fraktur by Kolb, and the trumpeting angels are based on those drawn by Eyer. The certificate was made for Rahel Stähr (b. April 9, 1827), whose family lived in Nockamixon Township, Bucks County, where two of Rahel’s siblings were baptized at St. Luke’s Reformed Church. This certificate notes that her maternal grandparents, Johannes and Esther Adams, were also her godparents; they lived in nearby Durham Township, Bucks County.

Lisa Minardi, an assistant curator at Winterthur Museum, is a specialist in Pennsylvania German art and culture.

This article was originally published in the Anniversary 2015 issue of Antiques & Fine Art magazine, a digitized version of which is available on afamag.com. Antiques & Fine Art, AFAmag, AFAnews, and AFA Publishing are affiliated with InCollect.com.

1. When residing in Meadowbrook, the Johnson’s collection was featured as the Lifestyle for this magazine. See “A Fancy for Color and Design: A Collection of Pennsylvania Folk Art (Spring 2004): 34–44.

2. On Durs Rudy’s metamorphosis booklets, see Joan Irving and Lisa Minardi, “A Metamorphosis: The Changing Nature of Fraktur Studies,” Antiques and Fine Art 10, no. 6 (Winter 2011): 327–329.

3. Donald M. Herr, “Christian Beschler: The ‘Sussel-Unicorn Artist,’” Antiques and Fine Art 8, no. 4 (Spring 2008): 150–57.