E. Popeye Reed: American Stone Carver

This archive article was originally published in the Autumn/Winter 2008 issue of Antiques & Fine Art magazine.

E. “Popeye” Reed (1919–1985) was an American original. A self-taught artist who carved in stone and wood, money was never the motive for this native Ohioan. Off-the-grid long before it was fashionable, he made almost everything he owned, down to the stone pipe he smoked. He once confided in an interview, “I’d like to carve till I die. I would just love to be carvin’ right up until the last minute…and say, ‘This is the end of a perfect day.”

I was a graduate student working on my MFA when I encountered Popeye’s work at the Ohio Gallery in 1981. This was Popeye’s first one-man show in Ohio; later that year, he had a one-man show at Equator Gallery in New York, curated by Jeff Way. After I bought a small sculpture on opening night, Popeye approached me and said, “You don’t have to pay these prices, son. Why don’t you come out to my cabin next weekend.” It was the beginning of a wonderful friendship that lasted until his death. A hard worker with an enormous zest for life and a great sense of humor, Reed was a natural at telling stories, which he relayed orally and through his sculpture.

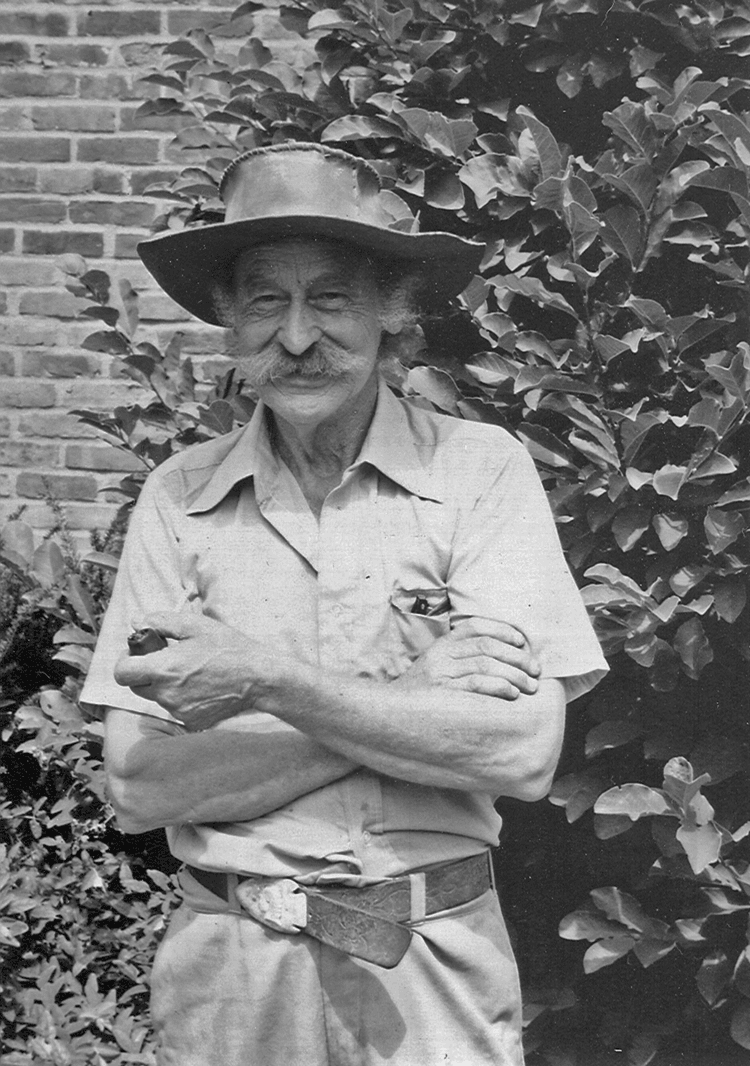

Popeye was the name he preferred—acquired because his forearms bulged with muscles, the result of handling stone—but he was born Ernest Reed in 1919, in Jackson County, Ohio, of Irish and Native-American heritage. He grew up in the Appalachian Hill country, quitting school after the eighth grade. He left home at fourteen, but never wandered far, supporting himself with odd jobs, and eventually ending up as a furniture maker. Popeye had no formal art training, but he had been carving since he was eight years old, mostly wooden animals, and by 1968, was earning a living as an artist. Popeye became a well-known figure in Jackson County, showing his work at flea markets and festivals, including state fairs, where often he could be found demonstrating stone- and wood-carving techniques. In 1980, he was featured in “Folk Art from Ohio Collections,” the publication of the Ohio State Fair.

- E. “Popeye” Reed (1919–1985)

Sphinx, 1968

Carved limestone, 18 x 12 x 5 in.

Courtesy of Mike and Cindy Noland

This winged sphinx is perhaps the most modern of all of Popeye's carvings. The wings act as a design element, and are more like airfoils on a hot rod than a naturalistic detail. Since limestone was not as readily available as native sandstone, Popeye reserved it for special pieces.

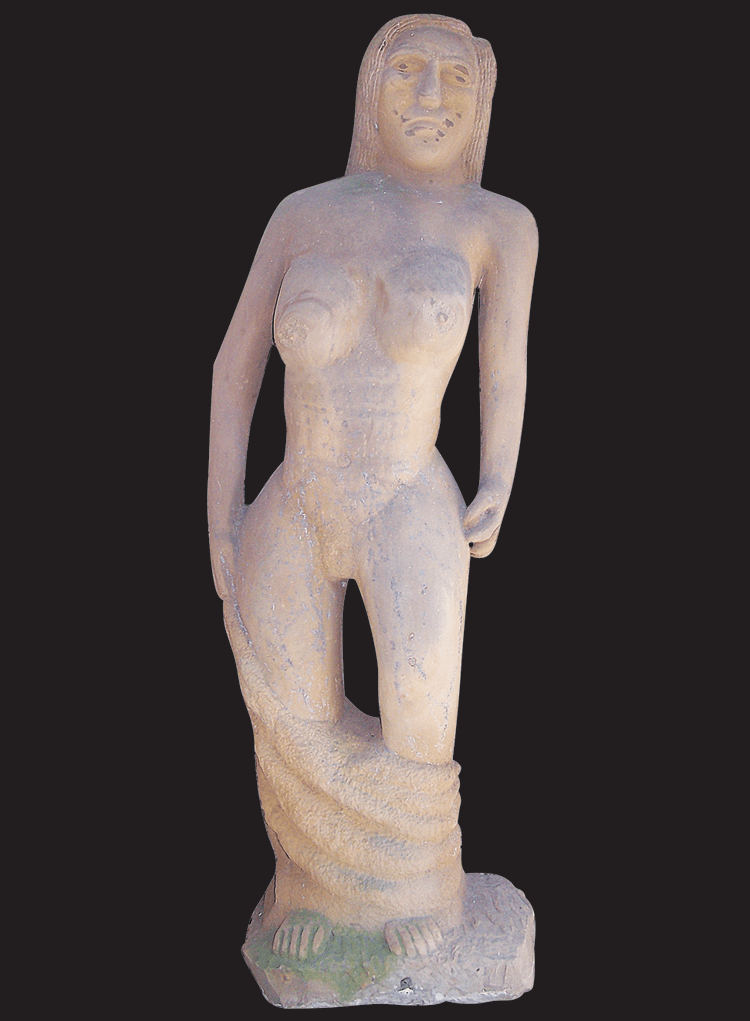

- E. “Popeye” Reed (1919–1985), Large Mermaid, 1980

Carved sandstone, 10 x 18 x 4 in.

Courtesy of Mike and Cindy Noland

Mermaids were a favorite carving subject for Popeye. He liked the myth of the half fish and half human creature, and developed his own version of the mermaid form. He carved them in different positions, but this is his most frequently seen pose. He also carved some in wood, including a flying mermaid with butterfly wings.

- E. “Popeye” Reed (1919–1985)

Adam and Eve, 1975

Carved limestone, 24 x 18 x 7 in.

Courtesy of Mike and Cindy Noland

Popeye liked to talk about how man and woman were created to work as a team. In this carving of Adam and Eve, their heads are combined as one, showing, in effect, that they have one mind. The composition is very modern in its use of negative space and in the way the figures together create a triangle.

- E. “Popeye” Reed (1919–1985)

Angel Relief with Self-Portrait, ca. 1973

Carved marble, 12 x 12 x 12 in.

Courtesy of Jeff Way and Carolyn Oberst

This is one of Popeye’s rare relief carvings in marble.The figure on the left is Popeye in his typical carving stance. The angel is bestowing on him his carving skills and artistic vision. In his lap is a stone ball representing the Earth. A second angel is reaching up to a duck, an emblem of good luck for Popeye. The border is etched with symbols that Popeye frequently used to represent himself in his work. He said they were spiritual symbols, and either couldn’t or wouldn’t say what they meant.

Sandstone became his signature material. Many of the larger pieces were from old building and bridge foundations from the Jackson County area. Often weighing several hundred pounds and extremely dangerous to move, Popeye would drag these pieces home on his homemade tractor, using old car tires to cushion the stones on a trailer. When he had them where he could work on them, he would split them into a workable size. He used a traditional carving technique of drilling holes and then pounding wedges in the holes until the stone split. It was a slow but exact way of sizing the stone. He would hold the stone between his knees when he carved, for most people a very uncomfortable way to work, but it suited Popeye. He would wet the sandstone down in order to minimize the dust and to make it softer to carve. He made or modified all of his stone carving tools. I remember one very impressive drill that he had made from an electric washing machine motor. It had no on-off switch, he just plugged it in when he wanted to work with it; he laughed when I pointed out how dangerous it was. In winter he worked in wood when it was too cold to work outside on stone.

Old books on mythology, ancient cultures, and the Bible were among the sources Popeye mined for his works, which ranged in size from less than a foot to five feet in height. About his influences, outsider-art expert Lyle Rexer has said, “Reed did what so many American artists have done in the face of extremely tenuous connections to a wider cultural and historical tradition — he made it up. He developed a formal approach all his own, bordering on abstraction, and incorporated all the motifs that came his way, from popular figures to religious icons, from imaginary creatures to beasts of the field. He was ambitious in the way Walt Whitman and Jackson Pollock were ambitious — to contain multitudes, to tell it all.”

My last visit with Popeye was in 1984 shortly before I moved with my family to Chicago. I soon got word that Popeye was in the hospital with terminal brain cancer. He died a few months later, posthumously receiving the Governor’s Award for the Arts in Ohio. Though he never realized his dream of having a big museum show, his work is in several major museum collections, including the American Folk Art Museum in New York. His reputation continues to grow.

—

Michael Noland is an artist, collector, curator, and speaker residing in Illinois.

This archive article was originally published in the Autumn/Winter 2008 issue of Antiques & Fine Art magazine.