Exhibitions Not to be Missed for June 25 - July 1

MUSEUM CURATORS TEND NOT TO EXERT THEMSELVES quite as much for their summer exhibitions, putting up thematic from-the-collection shows or recent acquisitions shows, but we’ve found a few exhibits for the next week that reflect some curatorial ambition.

|

| |

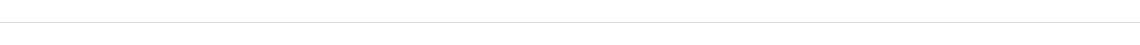

Unknown American makers and Daisy Studio (American, active 1940s). Studio Portraits, 1940s–50s. Gelatin silver prints. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Twentieth-Century Photography Fund, 2015, 2017 (2017.560, 2015.339, 2015.309, 2015.338, 2017.583, 2017.591, 2017.636, 2015.328, 2015.344). |

African American Portraits:

Photographs from the 1940s and 1950s

June 26 – October 8, 2018

On view at The Met Fifth Avenue in Gallery 852

Metropolitan Museum of Art

1000 5th Avenue, New York, NY 10028

Staring is rude, we all know, but artworks and especially photographs let us start with impunity. Who were these people? What were their lives like? Can we imagine ourselves in that setting, wearing those clothes? African American Portraits: Photographs from the 1940s and 1950s is made up of more than 150 portraits of African-Americans from the mid-twentieth century, part of a recent acquisition by The Met. We don’t leave this exhibit knowing too much about these people or who took their photographs, just how some element of the African-American community looked to have themselves portrayed during a time of war, middle-class growth and seismic cultural change.

|

Outliers and American Vanguard Art

June 24 – September 30, 2018

High Museum of Art

1280 Peachtree Street Northeast, Atlanta, GA 30309

What should we call these artists who didn’t study at salons or art schools? Folk artists, primitives, visionaries, naïve or outsider artists, isolates? Self-taught is another term, which may be less opinionated. The High’s term is “outliers,” and that may be fine, too. The work of more than 80 artists, represented by 250 or so paintings and sculptures, form the basis of this exhibition, which was organized by the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C.

|  | |

William Edmondson (American, 1874–1951), Jack Johnson, 1934-1941. Limestone. Newark Museum, Bequest of Edmund L. Fuller, Jr., 1985. William Edmondson attributed his foray into carving, begun after decades of working as a hospital janitor, to a vision from God. In the 1930s, Edmondson went beyond the tombstones he made for fellow Nashvilleans and filled his yard with sculptures of preachers, teachers, nurses, biblical figures, animals, and national celebrities he carved from local limestone. With the support of his black community, local white patrons, and an exhibition at The Museum of Modern Art in New York in 1937, Edmondson came to self-identify as an artist. The MoMA exhibition was the first one-person show by an African American artist in the institution’s history and the first by a self-taught artist. | Edward Hicks (American, 1780–1849), Peaceable Kingdom, ca. 1834. Oil on canvas. National Gallery of Art, Washington, Gift of Edgar William and Bernice Chrysler Garbisch. Peaceable Kingdom demonstrates an early example of a self-taught painter using art as an extension of his religious mission and professional trade. Originally trained as a coach maker and keen on painting elaborate decorations on his work, Edward Hicks fully embraced art making as a tool to support his Quaker ministry at a moment of schism in his religious community. In Hicks’s kingdom on Earth, predator lies down with prey; in the distance, William Penn, Quaker founder of the Pennsylvania colony, signs a treaty with representatives of the Lenape people. Hicks’s rich hybrid of historical and biblical imagery contributed to a revival of his reputation in the 1930s, when he was hailed as an “American Rousseau.” |

|

Face to Face: Portraits of Artists

June 26 – October 14, 2018

Philadelphia Museum of Art

2600 Benjamin Franklin Pkwy, Philadelphia, PA 19130

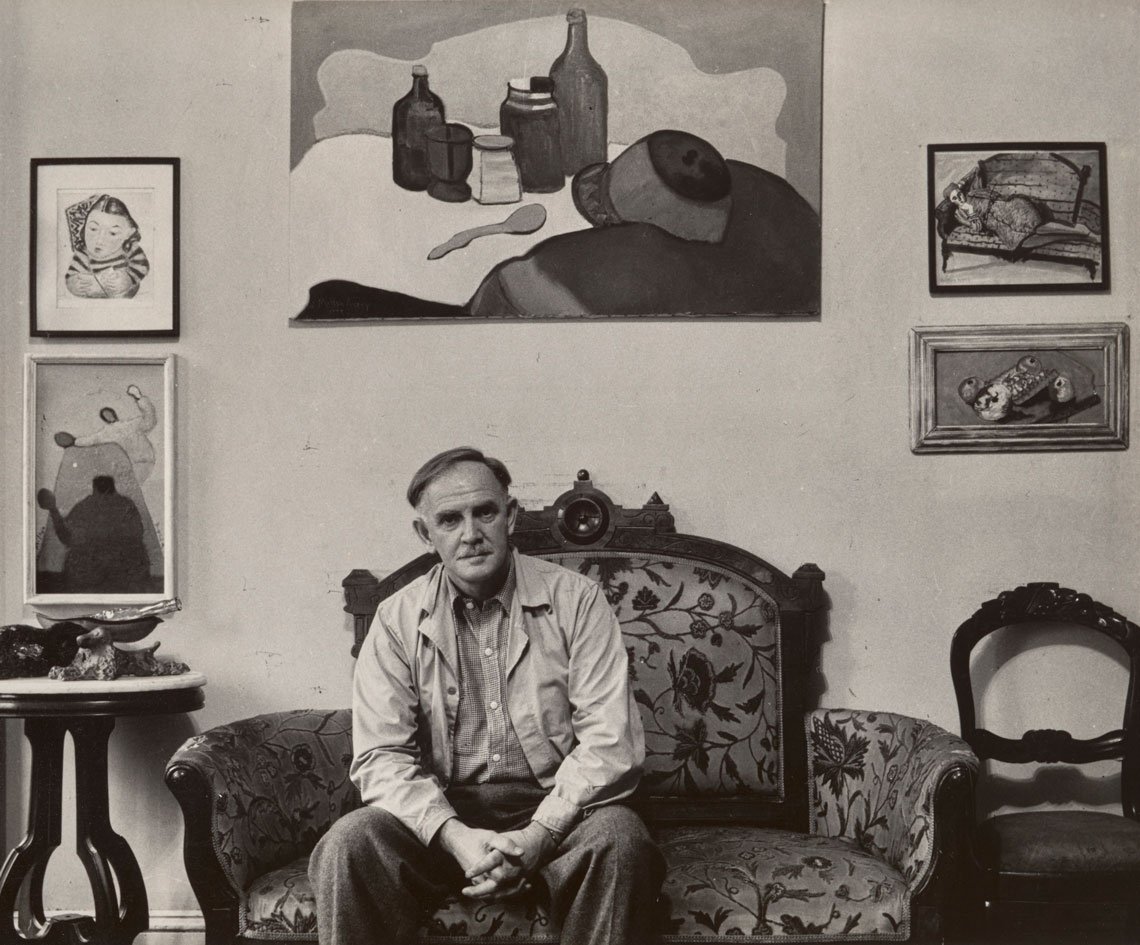

Does it make you appreciate an artist more if you know what he or she looked like? And, by artist, we are not just talking about painters and sculptors but also photographers (Berenice Abbott and Alfred Stieglitz), writers (James Baldwin, Zora Neale Hurston and Eudora Welty) and performers (Ella Fitzgerald, Ethel Waters and Bessie Smith). Still, the emphasis here is on fine artists, such as Milton Avery, Henri Matisse, Isamu Noguchi, Georgia O’Keeffe, Saul Steinberg, Robert Gwathmey, Jacob Lawrence, Marcel Duchamp, Thomas Eakins and Frida Kahlo. In all, more than 100 photographs are part of the display.

|  | |

| Milton Avery, 1944, by Arnold Newman. Gelatin silver print, image and sheet: 7-11/16 × 9-11/16 inches, mount: 16-15/16 × 14 inches. Philadelphia Museum of Art: Gift of R. Sturgis and Marion B. F. Ingersoll, 1945. | Isamu Noguchi, c. 1941-1945, by Arnold Newman. Gelatin silver print, image: 7-7/16 × 9-1/2 inches, sheet: 7 15/16 × 10 inches, mount (primary): 9 × 11 inches, mount (secondary): 16-15/16 × 13-7/8 inches. Philadelphia Museum of Art: Gift of R. Sturgis and Marion B. F. Ingersoll, 1945. |

|

|

| Rana Begum, No. 161, 2008; Paint on powder-coated aluminum, 98-1/2 in. high, 16 sections. Photo by Philip White. |

Heavy Metal — Women to Watch 2018

June 28 – September 16, 2018

National Museum of Women in the Arts

1250 New York Ave NW, Washington, DC 20005

Museums, especially those that exhibit contemporary art, have taken it upon themselves to inform visitors which artists the curators favor, the most notable example of this being the Whitney Biennial. The National Museum of Women in the Arts has its own series of shows, called Women to Watch, which is now in its fifth installment. This exhibition features sculpture and jewelry, as well as other uses of iron, steel, bronze, silver, gold, brass, tin, aluminum, copper and pewter. Among the featured artists from the United States, Europe, Central and South America are Cheryl Eve Acosta, Rana Begum, Carolina Rieckhof Brommer, Lola Brooks, Paula Castillo, Charlotte Charbonnel, Venetia Dale, Petronella Eriksson, Susie Ganch, Alice Hope, Leila Khoury, Holly Laws, Blanca Muñoz, Beverly Penn, Serena Porrati, Alejandra Prieto, Kerianne Quick, Carolina Sardi, Katherine Vetne and Kelsey Wishik

|

| |

| |

| Thomas Jayne and author Edith Wharton. |

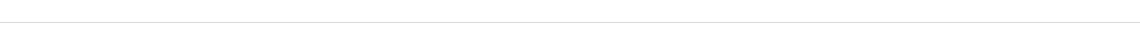

Classical Principles for Modern Design

June 28

The Mount

2 Plunkett Street, Lenox, MA 01240

Not an exhibition but a talk by Thomas Jayne, founder and principal of Jayne Design Studio and author of the recently published Classical Principles for Modern Design: Lessons from Edith Wharton and Ogden Codman’s The Decoration of Houses (Monacelli Press, 2018). Appropriately, this talk will be about the author Edith Wharton, and it will take place at The Mount, the home and grounds of writer Edith Wharton (1862-1937) in Lenox, Massachusetts, whose books were quite popular during her heyday (royalties paid for the house and its furnishings, no mean feat for a woman author) but less so now. The books most associated with The Mount are The Age of Mirth (1905) and Ethan Frome (1911), which she wrote there. The Age of Mirth tells a story of gilded age Manhattan, where she had lived off and on for much of her life before moving to Europe permanently in 1911. Visitors come to The Mount as much to learn about or honor the author as to see the place itself. Just like her good friend and fellow author Henry James, Edith Wharton had traveled extensively in Europe and developed a strong affection for European gardens and great houses. Certain architects of the day are associated with her house, but Wharton is believed to have contributed much of the design. Her 1897 book The Decoration of Houses expressed many of her ideas about functionality, proportion and symmetry, and Wharton “poured her heart and soul into The Mount,” said Susan Wissler, The Mount’s executive director. “The house and grounds are autobiographical and provide a window into her mind and passions. She didn’t live here that long, only three months a year for nine years, but the issue is not where she laid her head.” Thomas Jayne will focus on the influence Edith Wharton has had on the history of interior design and discuss the timelessness of the principles found in Wharton’s book.