Four Centuries at Historic New England

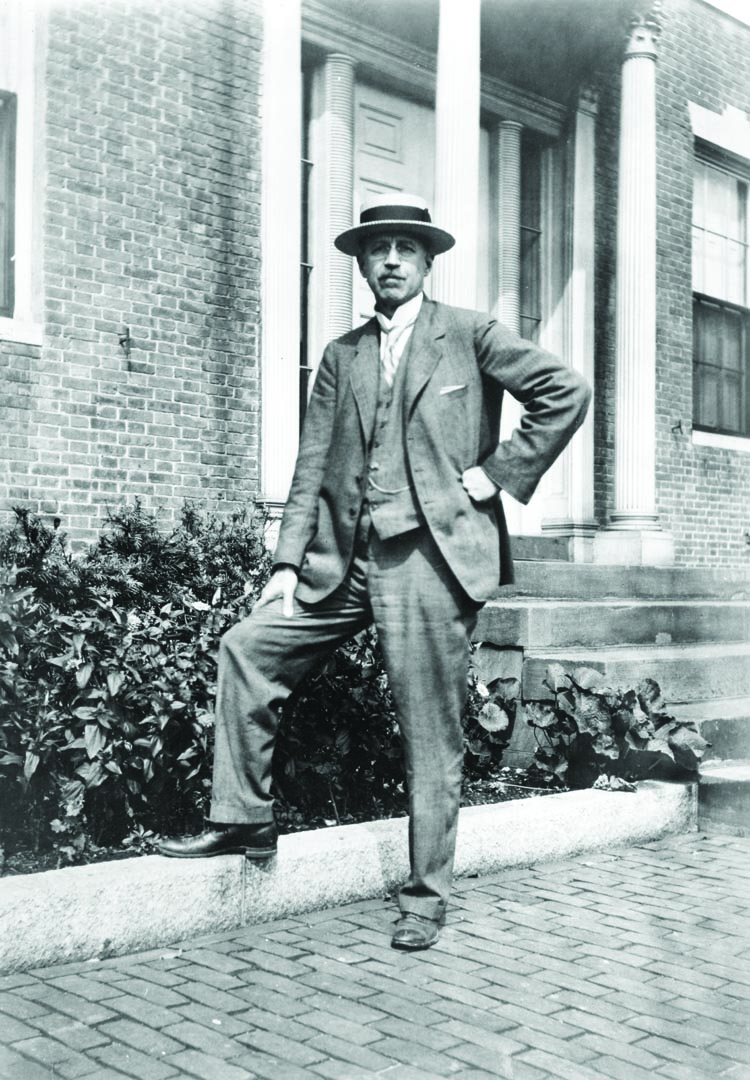

One hundred years ago, Bostonian William Sumner Appleton (1874–1947) (Fig. 1) decided to take a new approach to ensuring the long-term preservation of New England’s old houses. Until that time, efforts had been primarily reactive, with a group of antiquarians springing to action when an ancient structure was being threatened. Sometimes their efforts were successful, but just as often the battle was lost. In 1910, in a bold move, the Harvard educated, financially independent Appleton formed the Society for the Preservation of New England Antiquities—known today as Historic New England––to protect and preserve the architecture, decorative arts, and material culture of the region. During his lifetime the organization became a national leader in the preservation of historic homes.

Historic New England, which celebrates its centennial this year, owns and operates thirty-six historic sites, ranging from modest dwellings to mansions. It also preserves more than 110,000 objects and over a million photographs, architectural drawings, and historic records that tell the story of the New England from its settlement by Europeans through the twentieth century. Below are examples of houses and collections owned by Historic New England that span four states and four centuries of history.

The Seventeenth Century

Jackson House, circa 1664,

Portsmouth, New Hampshire

Appleton had a special interest in the seventeenth-century houses of New England, seeing them as particularly vulnerable because so many were buried under later accretions or were located in impoverished areas in towns. He made it his personal mission to identify and protect those earliest houses, some of which were still lived in by descendants of their first inhabitants. Among these buildings was the circa-1664 Jackson House (Fig. 2), which Appleton had first visited as a college freshman in 1893. Thirty years later, Appleton acquired the house for his fledgling preservation organization. After stabilizing the structure in 1924, he decided to leave the house intact, resisting colleagues’ urgings to restore the house to its earliest appearance (although evidence for the original leaded diamond-paned windows was so compelling that he decided to reproduce them). According to Appleton, the house was one of the best examples of a home that clearly demonstrated the course of its evolution. Defending his decision to preserve the layers of history, Appleton stated, “I much prefer the interesting alteration by some long dead generation of Jacksons.”

Early in his career Appleton began collecting architectural fragments that told the stories of the buildings that did not survive or had been dramatically altered. He searched throughout the region for objects that could be traced back to specific houses, like this rare pendant (Fig. 3) that once ornamented the second-story overhang of a seventeenth-century house in Newbury, Massachusetts. Appleton carefully recorded all the information he could find about each artifact, its corresponding house, and the early occupants, to ensure that an object and its history were never separated.

Appleton’s tireless efforts to preserve New England’s history went well beyond buildings to include their contents as well. Because the Jackson House was acquired with no family furnishings, it is shown empty in order to highlight its remarkable architecture (Fig. 4). Appleton’s ideal, however, was to acquire houses that could tell the complete story with generations of accumulated material culture that chronicled the occupants’ lives.

The Eighteenth Century

Sayward-Wheeler House, circa 1718

York Harbor, Maine

Although not directly involved in its preservation, Appleton was certainly familiar with the Sayward-Wheeler House (Fig. 5), for it was well known to antiquarians as early as the 1860s, and an article about the house appeared in Old-Time New England, the Society’s magazine, in 1938. Built in about 1720, the house was occupied by ship owner Jonathan Sayward and his family after 1735. It remained in ownership by Sayward’s descendants until it came to Historic New England in 1977. Described as “perhaps the best preserved household of the colonial era in America,” no other eighteenth-century house in the country can boast a more complete set of original furnishings.

One of Jonathan Sayward’s most prized possessions was the portrait of his daughter painted in 1761 (Fig. 6) by the English-trained artist Joseph Blackburn (1700–1780) who was living in nearby Portsmouth, New Hampshire, at the time. The painting shows a typically idealized image of eighteenth-century womanhood, with Sally, the Saywards’ only child, holding a basket of roses over one arm and a rosebud in her other hand. The painting hangs on the only wall in the house large enough to accommodate it, where it hung in Sayward’s time.

For those living through the early years of the Revolution in America, the future was not at all assured. As an outspoken Tory, Jonathan Sayward found himself stripped of political office, threatened by mobs, and living under virtual house arrest. Small wonder, then, that he suffered from sleeplessness. In his diary for May 12, 1777, Sayward wrote: “I heard the Clock every Hour Last night.” The clock that accompanied his restless nights (Fig. 7) remains in the house, anchored to the wall with the original cast-iron hardware.

At his death in 1797, Sayward left the house and its contents to his grandson, Jonathan Sayward Barrell, who continued the mercantile activities of his grandfather. Severely affected by Jefferson’s embargo and the War of 1812, Barrell went bankrupt and was therefore never able to modernize the house or replace the outdated furnishings of his grandfather. After his death, the property passed to his two unmarried daughters. Their frugal upbringing and their reverence for their venerable ancestor were responsible for keeping the house and its furniture intact.

In the sitting room (Fig. 8), an imported eighteenth-century looking-glass hangs on the original wooden battens, and the room’s cornice molding shows the cuts made to accommodate the mirror’s height. With seemingly reckless disregard for aesthetics, the Saywards also cut down the cornice of the desk and bookcase so that this useful piece would fit into the low-ceilinged room. The set of Queen Anne chairs, still with the leather upholstery purchased by Sayward, remain in place. The gate-leg table in the center of the room, almost certainly locally made, may have been a piece Sayward inherited. The prints over the mantel belonged to Sayward’s granddaughter, while the painting behind the door and the wallpaper and carpet came with later descendants.

The Nineteenth Century

Roseland Cottage, 1846, Woodstock, Connecticut

Like the Sayward-Wheeler House, Roseland Cottage came to the organization long after William Sumner Appleton’s death, and while it is unlikely that he ever knew much about the house, Appleton would have greatly appreciated it. To many of Appleton’s contemporaries, all things Victorian were abhorrent. But he was more broad minded. He acquired Victorian furnishings for the collections and worked strenuously with local groups to save the Morse Libby House in Portland, Maine, from demolition.

Roseland Cottage, with its distinctive Gothic tracery, stained–glass windows, and unexpected pink exterior is one of northeastern Connecticut’s iconic gems (Fig. 9). Built in 1846 for Henry Bowen and his wife, Lucy, by architect Joseph C. Wells, the house reflects the interest in the Gothic Revival that prevailed in the 1840s. Andrew Jackson Downing’s influential book Cottage Residences (1842) promoted the Gothic style for “men of imagination.”

The Gothic style, with its pointed arches, trefoils and quatrefoils, and its emphasis on extreme verticality, is clearly inspired by church architecture. The owner of a Gothic cottage, or of Gothic-inspired furnishings was signifying an attitude of upright moral virtue and the sanctity of a home. Few were better suited to it than Henry Bowen. He was one of the founders of The New York Independent, a weekly Congregational newspaper that advocated temperance and abolition. His local philanthropy included the restoration of the Woodstock Academy and improvements of the town common, culminating in 1876 with the creation of a pleasure ground, which Bowen donated to the town for public recreation.

The Bowens furnished Roseland Cottage with objects appropriate to its architecture (Fig. 10). The quatrefoils and arches of the suite of walnut furniture made for the double parlors echo the exterior of the house. The walls are decorated with religious and moralistic prints, family portraits, and landscape paintings of the surrounding region. The Lincrusta-Walton wall covering was installed when Bowen and his second wife redecorated in the 1880s.

The furniture includes an astonishingly large parlor suite of more than a dozen pieces—two settees, two window benches, armchairs, side chairs, two footstools—apparently made by the Brooklyn cabinetmaker Thomas Brooks (Fig. 11). In addition, there are hall furniture and bedroom suites in the Gothic style. The crib (Fig. 12), made of mahogany rather than the black walnut of the parlor suite, may have been ordered separately for the Bowens’ oldest child, Henry Eliot Bowen, born in 1845.

The Twentieth Century

Gropius House, 1938, Lincoln, Massachusetts

Another archetypal building in Historic New England’s collection is the Gropius House (Fig. 13). Built by Walter Gropius, founder of the Bauhaus school of design in Germany, the house startled neighbors when it was completed in 1938. Gropius had been invited to Harvard University to teach both faculty and students about his approach to architecture. With a modest budget, he constructed his version of a New England house to serve as a home for his family, a teaching tool for his students, and a calling card for his private practice. He used a combination of traditional building materials and modern technology to create a house made of wood, fieldstone, chrome, and glass block, and helped to usher in a new understanding of modern design in the region. Historian Lewis Mumford wrote in the Gropius’ guest book, “Hail to the most indigenous, the most regional example of the New England home, the New England of a New World.”

The interior of the Gropius House features large windows to take full advantage of the New England landscape (Fig. 14). Gropius designed each room around the Bauhaus-made furniture he and his wife had brought from Germany, which today represents one of the largest collections of original Bauhaus furniture outside of Europe. The majority of the pieces were designed by Marcel Breuer (1902–1981), who ran the Bauhaus furniture workshop from 1925–1928. Breuer’s tubular steel tables (Fig. 15) also served as stools, gliding effortlessly across the floor, and illustrating simplicity, functionality, and economy, the core values of the Bauhaus philosophy.

Gropius developed a deep fondness for Japan after a trip in 1954 and returned several times, bringing back something new each visit. He and his wife particularly loved a pair of stools (Fig. 16) by Sori Yanagi, a designer who worked in Tokyo. In addition to furnishings, the Gropiuses filled their house with paintings and prints from old Bauhaus friends such as Josef Albers (1888–1976), László Moholy-Nagy (1895–1946), and Vasily Kandinsky (1866–1944).

In the mid-1970s, when architecture of the modern movement had fallen out of favor, Gropius’ widow gave the house to Historic New England as a way of continuing her husband’s teaching. It is now the most visited museum in the collection, a fact that would certainly have surprised William Sumner Appleton. Still, he would undoubtedly appreciate that the Gropius House preserves and presents a story that is unique to New England, and part of the continuum that he identified back in 1910, when he set out to protect New England’s cultural heritage for the benefit of future generations.

All images courtesy Historic New England.