Four Centuries of Massachusetts Furniture

On the morning of May 11, 1972, fifty people gathered in the double-parlor of the Higginson House, an elegant Federal dwelling on Boston’s Beacon Hill that serves as the home of the Colonial Society of Massachusetts. The moment marked the start of a two-day conference on Boston furniture of the eighteenth century. Organized by Jonathan Fairbanks, then curator of American decorative arts and sculpture at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, and Walter Muir Whitehill, president of the Colonial Society, the event brought together such seasoned speakers as Richard Randall and Dean Fales as well as four young graduate students from the Winterthur program in early American culture. During the afternoon the conference moved to the Museum of Fine Arts for more presentations and a tour of a small exhibition of Boston masterpieces entitled A Bit of Vanity, Furniture of Eighteenth-Century Boston. The event concluded the next day back at the Colonial Society’s headquarters. Over the next year, speakers turned their talks into papers, and in 1974 the Colonial Society published Boston Furniture of the Eighteenth Century. The volume quickly became a standard reference for anyone interested in early American furniture.

- Fig. 7: Library table, Boston, Massachusetts, ca. 1860. Black walnut; H. 30½, W. 57, D. 42 in. Private collection. Owned by Justin Winsor (1831–1897), the eminent librarian of the Boston Public Library and later Harvard College. The carved faces on the rails depict William Shakespeare, Benjamin Franklin, George Washington, and Daniel Webster.

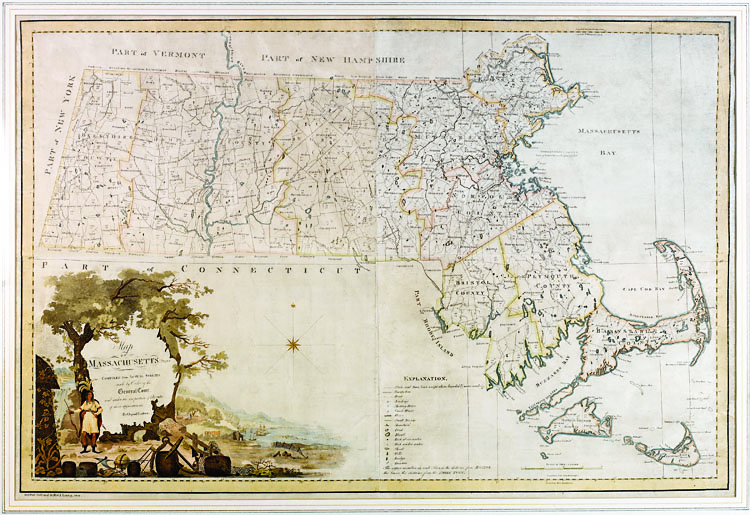

Over the past forty years, Boston furniture has remained a favorite of collectors. Yet, since the Colonial Society’s conference, only one seminar has addressed the subject, and, in that case, only the Federal era. To be sure, research has continued, but the results are widely scattered. In 2010, conversations among a few scholars sparked interest in a fresh look at Boston furniture—one that would consider a broader time period, re-visit past assumptions, and encourage new research. The Winterthur Museum agreed to host the event in 2013, and the Colonial Society kindly offered to serve again as the publisher of the papers. In addition, the Massachusetts Historical Society made its second-floor galleries available as a site for an exhibition of Boston furniture. It soon became clear that other Massachusetts museums had plans of their own for furniture exhibitions. Although the topics varied, they shared a commitment to celebrate the rich history of Massachusetts furniture (Fig. 1). A collaboration began to take shape; the conference and publication spawned a grand consortium. The result is Four Centuries of Massachusetts Furniture.

The project unites eleven institutions in an unprecedented partnership. Winterthur, the Colonial Society, and the Massachusetts Historical Society have joined with the Concord Museum, Fuller Craft Museum, Historic Deerfield, Historic New England, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, North Bennet Street School, Old Sturbridge Village, and Peabody Essex Museum in an ambitious schedule of landmark events, beginning in the spring of 2013. Seven exhibitions, three symposia, two major books, an online database of documented Boston furniture, enhanced cataloging of Massachusetts furniture at participating institutions, and dozens of public programs will provide the public with a visual feast. Tying together this bounty of activities will be a project website, www.fourcenturies.org. Its core components include not only a calendar of activities and links to furniture databases but also several unique educational tools. One such device, a visual timeline from the 1620s to the present, offers an interactive guide to Massachusetts furniture, from the elegant to the everyday. In sum, Four Centuries of Massachusetts Furniture promises to rewrite the record of the Bay State’s craft achievements.

|

The project kicks off with the Winterthur Furniture Forum (March 6 through 8, 2013). Thirty experts will assemble for lectures, workshops, and tours, to examine Boston furniture from the 1630s to the Civil War. A special exhibition of the best Boston furniture at Winterthur complements the conference and highlights such treasures as a rare seventeenth-century leather chair with original upholstery (Fig. 2) and grand bombé desk and bookcase (Fig. 3). After the conference, work will begin on preparing a selection of the papers for publication in the Colonial Society’s volume, Boston Furniture, 1630–1830.

During September 2013, a round of exhibitions in Massachusetts will begin, starting at Historic Deerfield and continuing in October with successive openings at the Massachusetts Historical Society, Fuller Craft Museum, Concord Museum, and Old Sturbridge Village. The display at Historic Deerfield, Furniture Masterworks: Tradition & Innovation in Western Massachusetts, examines regional identity. Seating and case furniture made in Massachusetts before the 1840s is as varied as the consumers and the craftsmen who created it. From Beacon Hill to the Berkshires, the extremes test the richness of the whole. Yet, the great variety in the Bay State’s furniture making begs the question: Why is the furniture so different statewide in each period from the seventeenth into the nineteenth centuries when so many other cultural, social, economic, and political traditions appear unified? There are at least two answers to that question. The first rests with the power of family networks in its control of mores and standards, capitalization of tools and labor, and accepted beauty and functionality. The second lies in the natural power of the landscape in its ability to feed, sustain, transport, and protect. The furniture-making traditions in western Massachusetts (Figs. 4 and 5) are the perfect laboratory for exploring the impact of family and landscape on the appearance of manmade goods. Through a wealth of diverse objects, Historic Deerfield will chronicle the changing face of regional expression over two centuries.

In early October 2013, the Fuller Craft Museum examines a far different subject. MASS Made: Contemporary Studio Furniture of the Bay State considers furniture making in Massachusetts over the past half century. Striking examples that document the continued production of custom furniture in the Colonial Revival style will face off against the free-spirited work of individual studio artists (Fig. 6). In addition, the exhibition will trace the impact of two influential initiatives: the cabinet and furniture-making program at North Bennet Street School and the program in artisanry begun at Boston University in 1975 and later moved to the University of Massachusetts, South Dartmouth.

Topics in the other exhibits range from rarely seen Boston furniture in private collections (Fig. 7) to the distinctive output of two Federal period craftsmen, William Munroe of Concord (Fig. 8) and Nathan Lombard of Sturbridge and Sutton, Massachusetts (Fig. 9).

A final exhibition, slated to open at the Peabody Essex Museum in 2014, examines the career of the eminent Salem cabinetmaker Nathaniel Gould (Fig. 10). His sophisticated bombé and block-front case furniture (Fig. 10) ranks among the finest offerings by any artisan during the 1760s and ’70s.

Four Centuries of Massachusetts Furniture is a unique achievement. Never before have so many august institutions in the Northeast joined forces to study, publish, display, and promote a single topic in the field of American art. The subject of Massachusetts furniture is a fitting one. Arguably no state has left a more remarkable legacy—from the earliest products of newly arrived immigrants in the 1620s and ’30s to the outstanding work of present-day studio furniture makers. We invite you to enjoy these groundbreaking events. Don’t settle for one or two. Make a pilgrimage to them all.

Four Centuries of Massachusetts Furniture is a collaborative venture of the Colonial Society of Massachusetts; Concord Museum; Fuller Craft Museum; Historic Deerfield; Historic New England; Massachusetts Historical Society; Museum of Fine Arts, Boston; North Bennet Street School;

Old Sturbridge Village; Peabody Essex Museum; and Winterthur Museum, Garden & Library.

This article was originally published in the Summer 2015 issue of Antiques & Fine Art magazine, a digitized version of which is available on afamag.com. Antiques & Fine Art, AFAmag, AFAnews, and AFA Publishing are affiliated with InCollect.com.