Gertrude Fiske: American Master

|

| Fig. 1: Gertrude Fiske (1879–1961), Saunterers—The Causeway, 1912. Oil on canvas, 20½ x 27 inches. Private collection. |

Gertrude Fiske (1879–1961) was an artistic virtuoso, considered to be one of the boldest and most talented painters of her time (Fig. 1). She was born into a prominent Boston family with direct ties to William Bradford, governor of Plymouth Colony. In 1904, she enrolled at the School for the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, and completed the full seven-year curriculum. The noted Impressionists, Edmund C. Tarbell, Frank W. Benson, and Phillip L. Hale were among her teachers. In addition to her formal studies at the Museum School, Fiske spent her summers in Ogunquit, Maine, in the company of fellow artists who made this seaside enclave their creative space. Among them was Charles Woodbury, whose influence on Fiske’s work cannot be overestimated (Fig. 2).

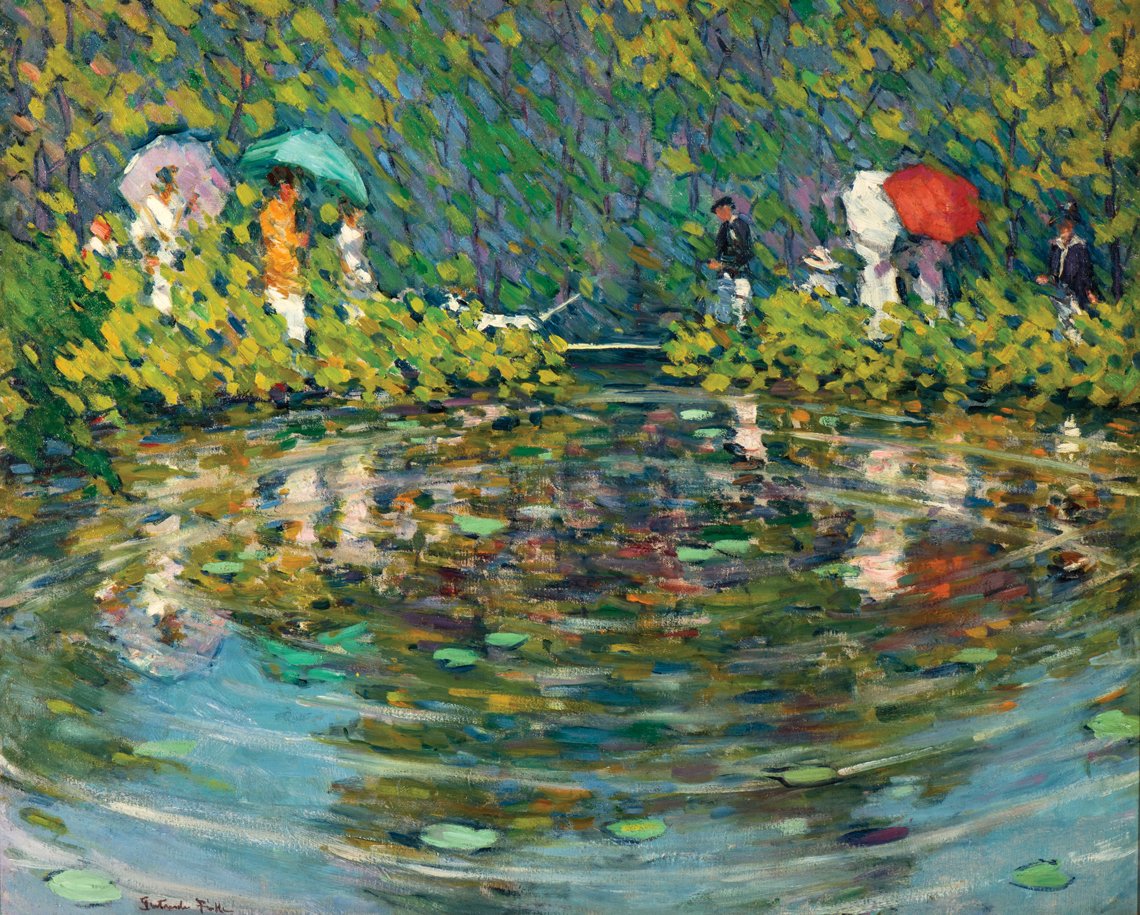

Fiske had the economic freedom to paint full time. Moreover, she had the talent and ambition to pursue this type of career. But most importantly, she had the genius to “see.” She was able to translate light, movement, gesture, and nuance to the delight of the art critics surveying her work in the early years of the twentieth century. The multitude of awards and prize winnings garnered during her career speak volumes for how her work was received. Her paintings resonate today with a bold energy that has not dimmed over time (Fig. 3). Considering the inherent disadvantage women had in the realm of the fine arts in the early twentieth century, Fiske’s success is a benchmark.

|

| Fig. 2: Gertrude Fiske (1879–1961), Old Cove, ca. 1922. Oil on canvas, 24 x 30 inches. Collection of Darin R. Leese and Frank E. Vandervort. |

|

| Fig. 3: Gertrude Fiske (1879–1961), By the Pond, ca. 1916. Oil on canvas, 29½ x 36 inches. Private collection. |

| |

| Fig. 4: Gertrude Fiske (1879–1961), Woman in White, ca. 1917. Oil on canvas, 36 x 29 inches. Private collection. |

Boston in Context

In the late nineteenth century, as a reaction to the effects of the Industrial Age in the United States, there was a desire to return to what was considered to have been a more genteel time in America. This desire expressed itself in the Colonial Revival style in architecture, decorative arts, and landscape design. The fine arts seized on this notion nowhere more consistently than in Boston. Tarbell, Benson, and Hale, all promoted some of the ideas of Colonial Revivalism to their Museum School students. They also taught the new Impressionistic methods coming from France. This meant painting en plein air, capturing fleeting moments of light, and using luminous colors. Most importantly, they emphasized the traditional technical skills of drawing and composition, and understanding the past masters. Added to these, were the underlying tenets of the Boston School: to paint genteel subject matter with a conservative approach (Fig. 4).

For women painters in those years, Boston was a paradox. It was at once accepting and even welcoming of female artists. The vast majority of students in the fine art schools were women. And unlike other parts of the country, Boston galleries readily opened their doors to the swell of women painters. But they were encouraged only as long as they stayed within the conventions of the day (Fig. 5). A woman’s success was not necessarily dependent on her talent, but rather on her willingness and ability to “paint within the lines” of social protocol. For instance, rendering the female form in a sophisticated, yet contained and banal manner, was expected from the Boston School. Many women artists resisted this lack of authenticity and sought instead an independent vision.

|  | |

| Fig. 5: Gertrude Fiske (1879–1961), Woman at Work, 1910. Oil on canvas, 23⅜ x 29¼ inches. Private collection. | Fig. 6: Gertrude Fiske (1879–1961), Mary, ca. 1920. Oil on canvas, 40⅛ x 30¼ inches. Davis Museum, Wellesley College; Gift of Andrew Willis, Harold Willis Jr., and Mrs. Gilbert Wilkinson (1969.46). Photo by Steve Briggs. |

Change came to Boston as a result of global events. The heavy toll of World War I meant, among other things, fewer men, which in turn meant women were put to work to replace them. With fewer men, marriage was no longer an inevitability for women. This enabled some women to live alone, or in community with other women, and to pursue their own ambition without society frowning upon these choices. In addition, the Women’s Suffrage Movement gave women a newfound sense of self and empowerment, regardless of their direct involvement with the movement.

The confluence of these events proved to be a turning point for many women who found the confidence to follow their calling. Gertrude Fiske is a prime example of an individual emboldened by her social context. Her daring work is a testament to this tide change. As a result of moving beyond convention, she produced brilliant and unexpected work for a woman in the early years of the twentieth century (Fig. 6).

|

| Fig. 7: Gertrude Fiske (1879–1961), Strollers, 1926. Oil on canvas, 36 x 40 inches. Photo by Jay Willis. |

Painting Women

After graduation in 1914, Fiske continued in the tradition of the Boston School, though by 1916, there was a distinct difference in her treatment of women on the canvas. Gone were the passive, domestic, interior scenes. Many of her models were now painted outdoors, in compelling compositions, revealing a newfound freedom (Fig. 7). Her work expresses a growing shift toward the portrayal of a more self-assured woman, reflecting her own growing confidence.

What Fiske shows us through her vibrant color pairings and bold compositions are real women in thought-provoking settings. In such paintings as Bettina (Fig. 8), the viewer is drawn to the authority of the sitter’s gaze, the striking palette, and the modern composition. These narratives are pensive, dynamic, and arresting. Bold color choice, matter-of-fact composition, and honesty of posture and gesture legitimize the sitter as a real woman of the time. The genius of this image lies in the balance Fiske created between the highly stylized background and her equally powerful subject. Here, Fiske underscores the place of women in their own right. The brilliant notes of blood-orange and the backdrop of varied, soothing blues and greens create a rich juxtaposition in Zinnias (Fig. 9). The young model in her plain summer dress is in deep thought. The simplicity of her gesture, expression, and composition against a landscape of sparring colors, makes this painting a resounding success.

|  | |

| Fig. 8: Gertrude Fiske (1879–1961), Bettina, ca. 1925. Oil on canvas, 36 x 30 inches. Private collection. | Fig. 9: Gertrude Fiske (1879–1961), Zinnias, ca. 1920. Oil on canvas, 40¼ x 30¼ inches. Collection of Mr. and Mrs. Richard M. Thune. |

Nude in Interior (Fig.10) is a profound and daring piece that speaks to the liberating forces occurring in society at the time and is an example of Fiske’s transition of the female model as moving from object to subject. This image shows the sitter, not as a component of the scene, but as the scene itself. The viewer is drawn to her expression and her body language. As compelling as the subject is, the viewer is directed to the image of the painter at work reflected in the mirror. This is a tool that Fiske used repeatedly to underscore the importance of her trade.

Bird of Paradise, Sleeping Nude (Fig. 11) was both commended and dismissed by critics. Controversial because of its honesty, conservative critics felt it was scandalous, while others praised it for its confidence. Fiske painted several nudes, but none quite as provocative and intimate as this painting. Here, she offers an unusual presentation of a foreshortened figure shown blissfully relaxed and unaware. The warmth of the air and textiles are palpable. Combined, these features create an honest portrayal of a real woman when no one is looking.

|  | |

| Fig. 10: Gertrude Fiske (1879–1961), Nude in Interior, ca. 1922. Oil on canvas, 30 x 36 inches. Private collection. | Fig. 11: Gertrude Fiske (1879–1961), Bird of Paradise, Sleeping Nude, ca. 1916. Oil on canvas, 33½ x 42 inches. Private collection. Photo courtesy of Vose Gallery. |

| |

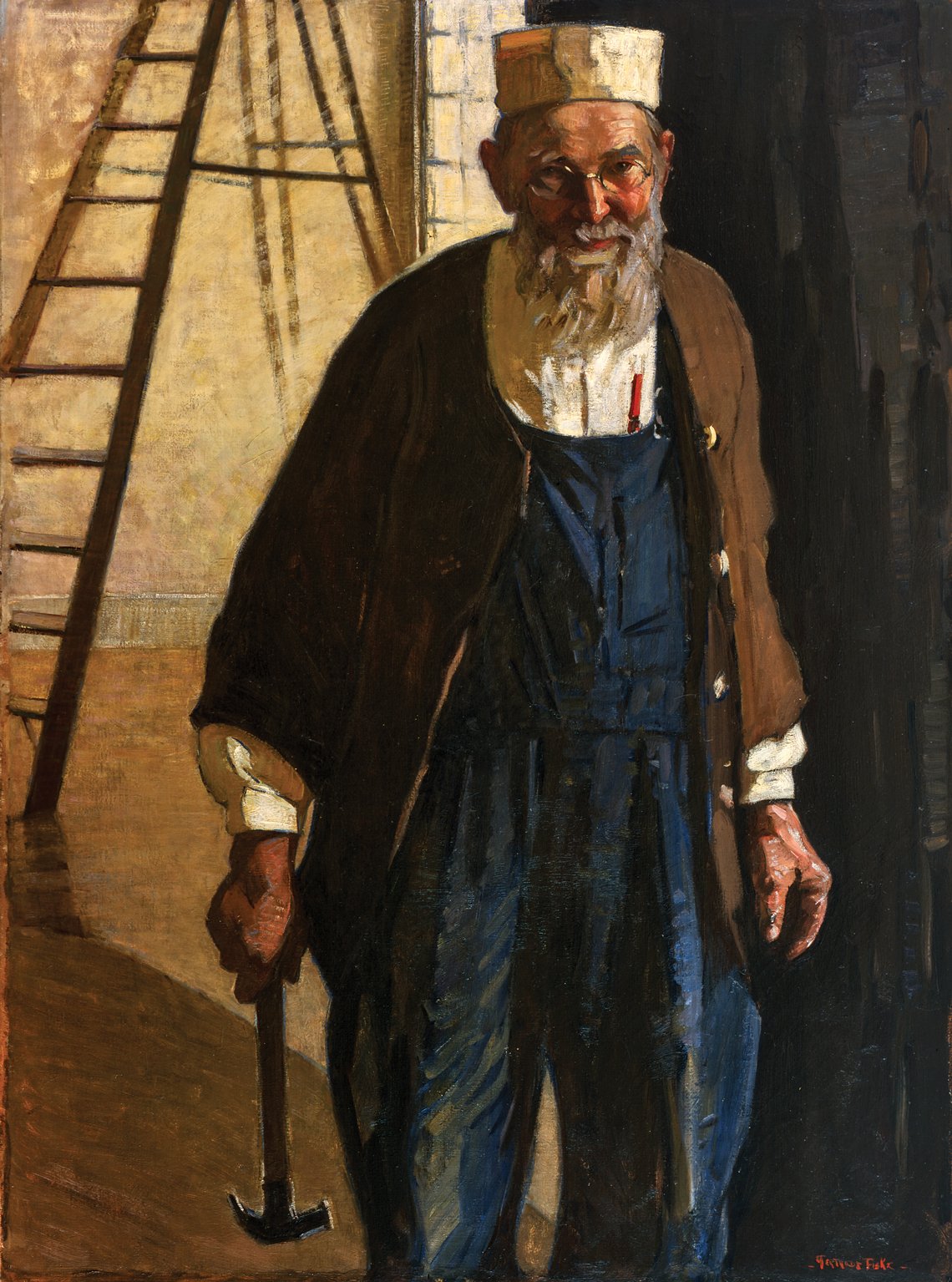

| Fig. 12: Gertrude Fiske (1879–1961), The Carpenter, ca. 1922. Oil on canvas, 54¼ x 40¼ inches. Farnsworth Museum of Art; Gift of the Estate of Gertrude Fiske (66.1529). Photo by Alan Lavallee. |

“A Virile Note”

Toward the end of the nineteenth century, art critics used feminine qualities as the high standard of art. The goal was to convey propriety and style, beauty and refinement. The early years of the twentieth century brought with it a backlash. Fearing an “effeminization of American culture,” art critics began to use and overuse the word “virile,” as they looked for a distinctive American style. Paintings described in this way had a robust quality, with a depth of technique and strong evidence of the artist’s hand.

Not surprisingly, Gertrude Fiske’s work was described as virile. Appointed as the first woman ever to the Massachusetts State Art Commission in January 1930, the Boston Globe described her many achievements and awards, one of which was as “the founder of the Concord Art Association, another virile and high-class organization.” More importantly, they go on to say that Fiske “always had a strong artistic individuality of her own, commenting, “There is a note of personal distinction in all of her work—a virile note” (Boston Globe, January 9, 1930).

It was Charles Woodbury who, as mentor and friend, supported Fiske in her exploration of her authentic and distinct voice in art. He encouraged all of his students to paint the forces they saw in front of them, and the stylistic singularity seen in Fiske’s portraits, landscapes, and figure paintings, shows her response (Fig. 12).

Gertrude Fiske: American Master, will be on view at Discover Portsmouth in Portsmouth, New Hampshire, from April 6 through September 30, 2018. For more information, see www.portsmouthhistory.org. It is accompanied by two companion exhibitions: Sisters of the Brush and Palette, which includes works by Susan Ricker Knox, Anne W. Carleton, and Margaret Patterson, all contemporaries of Fiske, and Seacoast Masters Today, with paintings by Amy Brnger, Pamela duLong Williams, Donna Harkins, and Sydney Bella Sparrow, all of whom work in the vibrant tradition of the arts on the Seacoast.

Lainey McCartney is curatorial associate at the Portsmouth Historical Society and the curator of Gertrude Fiske: American Master. This article is based on Gertrude Fiske: American Master, with Sisters of the Brush and Palette and Seacoast Masters Today, by Lainey McCartney, with contributions by Carol Walker Aten and Richard M. Candee (Portsmouth, N.H.: Portsmouth Marine Society Press, 2018).

Unless otherwise noted, all photographs are by Jeremy Fogg.

This article was originally published in the Summer 2018 issue of Antiques & Fine Art, a fully digitized edition of which is available at www.afamag.com. AFA is affiliated with Incollect.