Golden Girl by Augustus Saint-Gaudens

The Regilding of Saint-Gaudens’ Diana

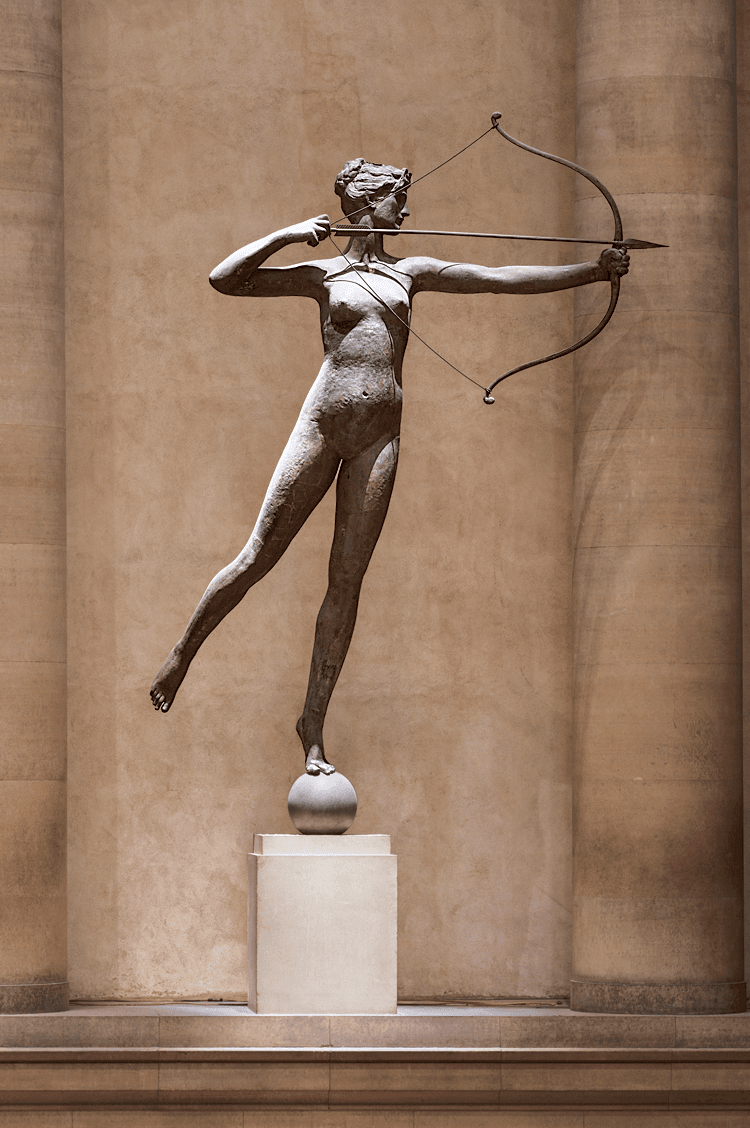

It has been one hundred and twenty years since Diana, lithe goddess of the hunt and the moon was installed atop the tower of New York City’s second Madison Square Garden (Fig.1), then located at Madison Avenue and 26th Street.1 The gilded copper statue, at the Philadelphia Museum of Art since 1932, was designed by Augustus Saint-Gaudens (1848–1907), a good friend and collaborator of the Garden’s architect, Stanford White (1853–1906). White envisioned a glittering icon signaling the location of the most important entertainment emporium of the day, created at a cost of more than $3,000,000 and containing an amphitheater, theater, concert hall, roof garden and café. A 1901 New York City visitor’s guide noted “The structure is popularly regarded as the most beautiful piece of architecture in the city…whether we see it by day, the tower rising against the blue sky and the finial Diana glorified by the sun; or when illumined by night (Fig. 2), the graceful lines of the tower are half-disclosed and half-suggested, and Diana reveals herself to us in the radiance of electric light.” Indeed, Diana was the reigning goddess of lower Manhattan until 1925 when the building was demolished. For seven years she languished in storage until she entered the collection of the Philadelphia Museum of Art, where she has recently undergone conservation efforts to restore her gilded brilliance.

|

|

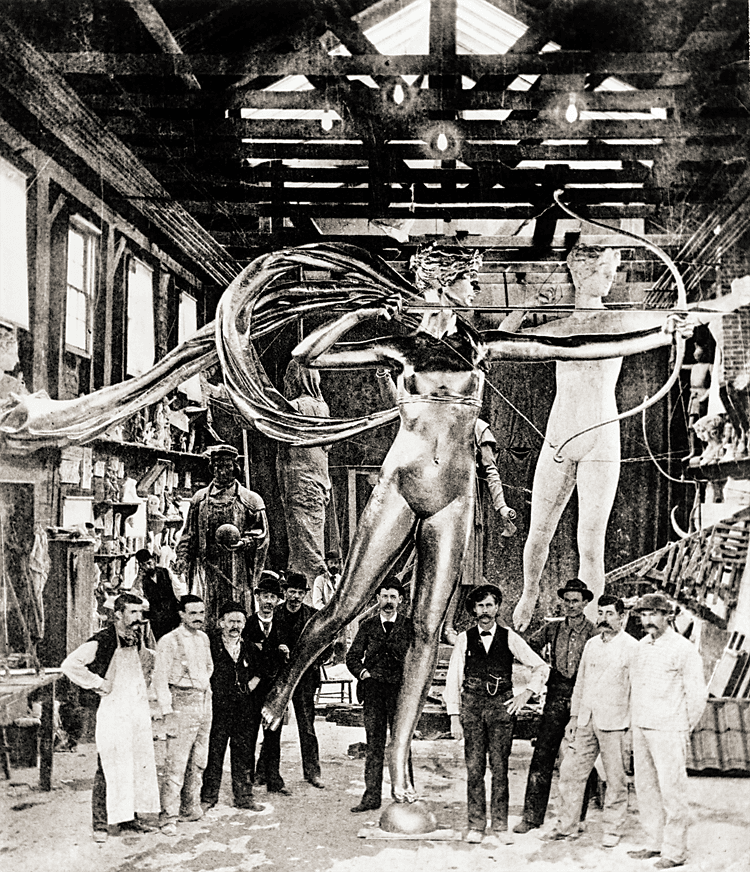

The reason for Diana’s installation was White’s competitive nature. The 300-foot Garden tower drew attention to the venue, making it among the city’s tallest structures. The ever-ambitious White, however, was compelled to compete with Joseph Pulitzer’s newly finished skyscraper for the World newspaper, which at 348 feet was the tallest building in New York. Aiming to have his tower reach higher than Pulitzer’s, he asked Saint-Gaudens to model a female figure as a weathervane finial. The sculptor, already nationally acclaimed, welcomed the opportunity to fashion his first female nude. She was fabricated in hammered and gilt sheet copper by the Mullins Manufacturing Company in Salem, Ohio (Fig. 3). Saint-Gaudens’ first Diana, completed in 1891, was 18-feet in height and deemed incompatible in scale with the tower.2 Two years later it was replaced by a smaller, more elegant version more diminutive by approximately five feet. When she was hoisted in November 1893 she received rave reviews from critics and public alike. Ultimately, Diana never cast her eyes downward toward the World, but she certainly held her own in the city’s skyline.

Saint-Gaudens took pains to double gild Diana to avoid the darkened, corroded surface that befell outdoor sculpture. Her brilliance was magnified by a circle of incandescent lights below her feet. However, her gold coat deteriorated quickly and was almost completely gone by the time she was lowered in 1925. Her arrival at the PMA in 1932 coincided with the Depression, so regilding was not undertaken until recently. Given the debacle over the harsh regilding of the Sherman Memorial in New York in 1934, and again in 1990 (Fig. 4)3, the task to restore gilding to Diana required caution and expertise. With funding from a Bank of America grant, a team of conservators and curators based at the PMA has been able to correct mechanical instabilities, remove corrosion, and restore the traditional gold leaf gilding. The team has used the artist’s original instructions for the gilding and toning of his statues, having learned he preferred a matte surface, and used acids and paints for toning down the gold.4 Given her indoor location, careful toning adjustments plus new lighting and background have given Diana a renewed majestic presence. A veritable symbol of the museum, she now glows as a goddess should (Figs. 5, 6).

Cynthia Haveson Veloric is a researcher in the American Art department at the Philadelphia Museum of Art.

Published in the Autumn 2014 issue of Antiques & Fine Art magazine, in tandem with InCollect.com. The entire issue is available on afamag.com.

2. After removal, the first Diana was exhibited at the Chicago World’s Fair of 1893 and later damaged in a fire. Its whereabouts is unknown. A patinated bronze reduction of the second Diana, made 1893–1894, is

in the collection of The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

3. On both occasions, the gold leaf was not matted or toned down. There was public and professional outcry after both regildings. The Central Park Conservancy completed a third restoration and regilding in fall 2013. They used best practices technically and also adhered to the artist’s original intentions regarding finishes.

4. The PMA has found period letters from Saint-Gaudens to White that include references and instructions for gilding, and evidence is also in the artist’s son Homer’s biography of his father (1913).