Grandeur in the White Mountains: Art, Architecture, and Automobiles

The Collections of William Batterman Ruger, Jr.

- Central to the grand foyer and living room are a set of four chairs with carved and gilded arms in the form of griffins. Made for MGM Studios, the chairs were props in the 1943 movie The Picture of Dorian Gray, starring Hurd Hatfield, an acquaintance of Rugers for many years. A Chippendale looking glass is mounted at the stair landing. Several bronzes by Remington, and Austrian sculptor Friedrich Goldscheider’s (1845–1897) 1890 Lady Walking a Panther on a Floral Leash, are strategically placed for visual effect.

A winding drive leads up to this pale-yellow Victorian house, sitting against a background of open fields with views of the surrounding mountains. The 1872 mansion, with a four-story russian domed tower at its center, is a mixture of Late Gothic, Queen Anne, and Romanesque Revival details.

Its owner, William Batterman Ruger Jr., or Bill Ruger, as he prefers to be called, is the eldest son of William B. Ruger Sr. the legendary gun designer and cofounder of Sturm, Ruger and Company. Since his retirement from the company in 2006, after a forty-two year tenure, Bill Jr. has pursued his many interests in architecture, automobiles, and art.

Bill extends a warm greeting to visitors in the entry hall and main living room of his residence. The substantial space features carved oak beams with large brackets overhead and Tudor paneled walls. Several Remington bronzes are displayed on plinths or tables, and a tondo relief by Augustus Saint Gaudens, depicting Robert Louis Stevenson and his poem Underwoods, is mounted against paneling at the base of the main staircase. Saint Gaudens was a frequent visitor to the house at the turn of the twentieth century, as were such other luminaries as artist Maxfield Parrish, financier J. P. Morgan, and industrialist Cornelius Vanderbilt. Presidents Theodore Roosevelt, Grover Cleveland, Herbert Hoover, Woodrow Wilson and Prince Edward VII toured or hunted in the adjoining parkland and were likely visitors to the mansion.

Doorways opening off the entry hall lead to the front parlor, dining room, kitchen, and sitting room. A hallway, with a classical, geometric aesthetic and blue and golden palette, separates the original house from its 2005 addition. The hallway leads to the barrel-vaulted study, its ceiling covered with twenty-two-karat gold leaf, which reflects the light of several Tiffany lamps, creating a warm glow in the cozy room reminiscent of a railway car. The Vulcan, a statue on the back lawn, is visible through windows.

“I tend to buy objects to be useful and comfortable and that go together attractively, whether they are paintings or furniture or rugs. My motives are mostly creating the atmosphere and total decorative effect of a given room or a given area,” says Ruger, who has focused his art and furniture collections to complement the Victorian residence.

The mansion is an eclectic mix of three different time periods, seamlessly joined together. The oldest section was originally an 1810 farmhouse measuring thirty-by-thirty-feet, where Long Island Railroad magnate and real estate developer Austin Corbin was born. In the 1870s, Corbin returned to his birthplace and purchased his family homestead. He tore down all but his birth room and constructed a rambling Victorian mansion around it. Corbin then built a suspension footbridge across the Sugar River in front of the house—the cable anchors of the footbridge can still be found on the riverbank—to provide access to his private railroad siding near the Northville Depot, where he kept his private railcar. Northville Farm, the name he gave his estate, served as his summer residence and refuge from the heat and humidity of Manhattan.

Over the next twenty years, Corbin bought twenty-five thousand acres of surrounding farmland and established a game preserve called the Blue Mountain Forest Association and sometimes referred to as Corbin Park, which successfully prevented the extinction of the buffalo. The association is now a club of thirty-five, of which Ruger (and his father before him) is a member. Says Ruger, “We don’t have American Bison anymore but…it’s an important habitat that’s part of the greenway from the Monadnock region to the White Mountains.”

- This magnificent cabinet by Herter Brothers of New York was made for Thurlow Lodge in Menlo, California, 1875. It is the first piece of Herter furniture that Ruger acquired at auction that had been owned at one point by Universal Pictures. The carving, highlighted in gilding, is both organic and architectural. The pier mirror is elaborately carved with cranes standing in reeds and leaves, their posture symbolizing eternal vigilance, with one foot raised and holding a rounded stone (if they sleep, they’ll drop the stone, so must remain awake and on guard). Because of its use as a movie prop, some of its delicate elements were lost; it had also been painted from time to time to achieve specific scenic effects. Research was conducted at the Smithsonian Institution to determine the original finishes, which were restored by conservator and furniture restorer Mark Adam. In the foreground is a gilded center table by Pottier and Stymus, circa 1868. The top is a single large piece of onyx. It was originally commissioned for the Stewart House in lower Manhattan.

With the passing of his father, Austin Corbin Jr. inherited the estate and managed the adjoining Corbin Park until his death in 1938. The property was sold outside of the family in 1940; Bill Ruger acquired it in the 1980s.

Today, Northville Farm spans five hundred acres of woodland forest and rolling meadows bordered by fieldstone walls. In 1989, Mr. Ruger began an extensive and faithful restoration of the mansion and outbuildings. Besides the house itself, this included a four-bedroom guesthouse, a post and beam barn, two large sheds, and a private free standing library building.

In 2005, Ruger added the gallery—a polychrome slate-roofed great room—the gold-leafed, barrel vaulted study—built to house his nineteenth-century art and furniture collection—and a garage and a porch with a balcony. Designed by architect Frederick W. Atherton, the gallery has gilded decorative plaster ceilings and elaborately carved casework. The inspiration for the room, and its focal point, is the 1872–1873 standing cabinet with mirror made by Herter Brothers of New York. This grand statement of opulence was part of the 1872 commission for former California Governor and United States Senator, Milton S. Latham (1827–1882), who had the furniture custom-crafted as a gift for his new bride and their new home, Thurlow Lodge in Menlo, California, purported to be the largest home in California at the time. Unfortunately for Latham, he lost his fortune and died bankrupt in New York at age fifty-four. After Thurlow Lodge was torn down in 1942, the contents of the house went to auction. Universal Pictures and Warner Brothers Studios bought some of the furniture to use as props. The elaborately carved tall cabinet and a set of chairs were featured in the films Ghost and Scarface, and may also have been used for other movies.

Architect and interior designer David Parker, an old friend of Ruger’s, alerted him to the fact that the Herter Brothers cabinet was at auction in San Francisco. Parker purchased the heavily carved cabinet with pier mirror on Ruger’s behalf. It arrived in nine crates. In good condition structurally, considerable work was required to restore its original finish and carvings. When Ruger discovered R. Mark Adams, a conservation and restoration expert who specializes in Herter Brothers furniture, was from the same telephone exchange as his own, Ruger was convinced his acquisition and the room he built to hold it was “meant to be.” After a meticulous five-year restoration, the rosewood, maple, and walnut cabinet with mirror anchors the east end of the gallery. Six additional Herter Brothers pieces, along with a French cabinet, are displayed along the perimeter of the room.

- The Gallery was designed by architect Frederick W. Atherton. The coffered ceiling is decorated in a style derived from the Lockwood Matthews house in Norwalk, Connecticut, decorated by the Herter Brothers firm of New York (active 1864–1906). The ceiling was embellished in this manner so it would be in keeping with the half dozen examples of furniture by Herter Brothers and other firms of the period that are displayed in the gallery. The ceiling details were executed by John Canning Studios of Cheshire, Connecticut, who also worked on restoring the Lockwood Matthews house and is known for restoration of the Grand Concourse ceiling at Grand Central Station in New York and the interior of Radio City Music Hall. The chandeliers are Bohemian crystal from the Czech Republic.

- This 1872 Herter Brothers cabinet is one of four known related pieces. One is in a New York apartment with interiors by David Parker, which was featured in the 13th Anniversary issue of Antiques & Fine Art. Another is in the Los Angles County Museum of Art, and the fourth is in a private collection believed to be undergoing restoration by Mark Adams. The primary woods are American walnut and rosewood, in combination with a rouge griotte marble top and profuse carving, gilding, and inlay work.

- This circa-1868 French cabinet is by Charles Guillaume Diehl (1811–1885), with bronze inlay and white marble top. There is a similar cabinet in the Musée d’Orsay in Paris. The museum provided assistance for this example in guiding the replacement of some minor losses to the gilded bronze. The two sculptures to the left are from the Japanese Meiji period (1868–1912). The medium size stalking panther, is by Alexander Proctor (1860–1950). The top central painting, Off the New England Coast, is by nineteenth-century Florida artist Laura Woodward (1834–1926).

- The carved walnut Herter Brothers chairs are from the 1872 Thurlow Lodge commission. They were acquired from Warner Brothers Studios. Believed to be from a set of eight, another of the chairs is in the Chrysler Museum in Norfolk, Virginia, and a further two are at Stamford University.

Ruger chooses paintings he considers attractive, serene, or scenic, and that fit in with the overall décor, regardless of whether the artists are well known or not. Some, such as those on the right wall, have a New Hampshire subject or are by local artists, and consequently have a cultural, historic, or artistic relevance to the house. On the opposite wall hang works by Massachusetts artist Charles Edwin Lewis Green (1844–1915). The collection also includes paintings by Hudson River Valley artists Albert Bierstadt, Alfred Thompson Bricher, Laura Woodward, and Levi Wells Prentice.

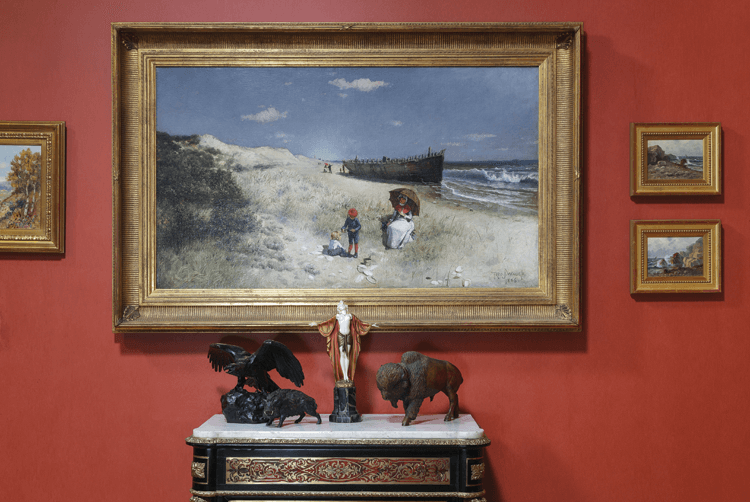

- This delightful beach scene is by Frederick Judd Waugh (1861–1940). A native of New Jersey, Waugh painted abroad before settling in Provincetown, Massachusetts. He is best known for his seascapes. Centered on the cabinet is the 1925 Ferdinand Preiss (1882–1943) sculpture, Spring Awakening, of ivory and polychrome bronze. The bronze Eagle is by Antoine Louis Barye (1795–1875). The wooden carved buffalo and small bronze wild boar with ivory tusks are by artists unknown and represent two of the animals that once thrived in the adjacent Corbin Park hunting preserve.

- This 1872 Renaissance-Revival cabinet is part of the Herter Brothers commission for Thurlow Lodge, the Menlo Park, California, mansion of Milton Slocum Latham, since razed. The cabinet, along with several other Herter Brothers objects in the collection, was later owned by Warner Brothers Studios. Mr. Ruger acquired the objects at auction in New York. Generally in good condition, losses to areas of finish, gilding, and carved details have been restored.

- The serene image, Flute Serenade (1885) by De Cost Smith (1864–1939), is centered above the folio cabinet. Smith, who was raised in western New York, formed an acclivity for native peoples. During his travels, he painted western tribes, learned several native dialects, and wrote about his experiences.

- revious page: One of numerous bronzes in the collection, this equestrian statuette is by Alexander Proctor (1860–1950), who spent the summer of 1903 or 1904 in Croydon, New Hampshire, near Ruger’s home. The Morgan horse, after which Proctor’s statuette is modeled, was owned by Austin Corbin Jr. who lived in this house at the time. The sculpture was cast at the Gorham Foundry in Providence, Rhode Island.

Directly above Proctor’s bronze, is a circa 1880s beach scene by New England painter Alfred Thompson Bricher (1837–1908), who specialized in coastal scenes. Surmounting the Bricher is Adirondack Lake, a work by New York artist Levi Wells Prentice (1851–1935), known for highly finished still life paintings and landscapes.

Referring to another Herter piece, Ruger notes, “I purchased the Herter Brothers cabinet with the rouge griotte marble top from Margot Johnson. This cabinet is very much like a cabinet from the 1872 Herter Brothers Thurlow Lodge commission, but is larger and more elaborate.” The remaining Herter Brothers furniture in the gallery was purchased at auction at Bonhams in New York City, and incredibly includes pieces from the 1872 Thurlow Lodge commission—a folio cabinet, a pair of large carved chairs, and a small lamp stand. A Herter Brothers pedestal in the form of carved birds was also acquired from Bonhams, but is not believed to be from Thurlow Lodge, though it is of the same grand American Renaissance-revival style.

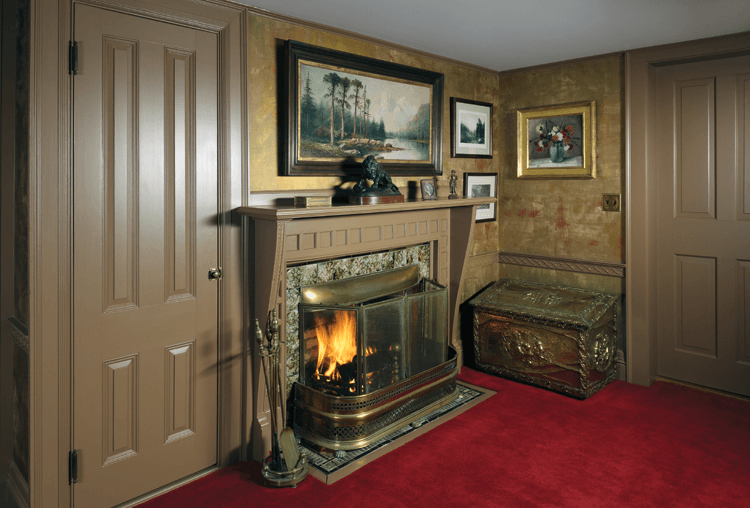

On the gallery wall directly opposite the large Herter Brothers cabinet with mirror is a fireplace with over-mirror designed by Atherton. The carvings and decorative motifs used in the fireplace surround echo those found in the tall cabinet, while the hearth is of the same rouge griotte marble as used on the cabinet noted previously, a smaller cabinet, and a nightstand. Both the mirror in the fireplace and the grand cabinet with mirror are perfectly aligned so that the room and pair of ten-foot crystal chandeliers reflect each other into infinity.

Not all of the furnishings in Ruger’s collection were bought at auction. Some were inherited from his mother, including an 1870 Alfred Thompson Bricher painting, a pair of nineteenth-century reproduction Louis XVI gilded chairs she obtained at an MGM Studios auction, and two Turkish chairs and sofa from the 1870s, which Ruger upholstered in three complementary patterns.

From his father, Ruger inherited a Tiffany floor lamp with a bronze patina finish and the 1903 Alexander Proctor statuette of The Warrior on Horseback. “My late father was most interested in the history and artistic achievements of this period in America and they also represent my own interest in American art and history of the time.”

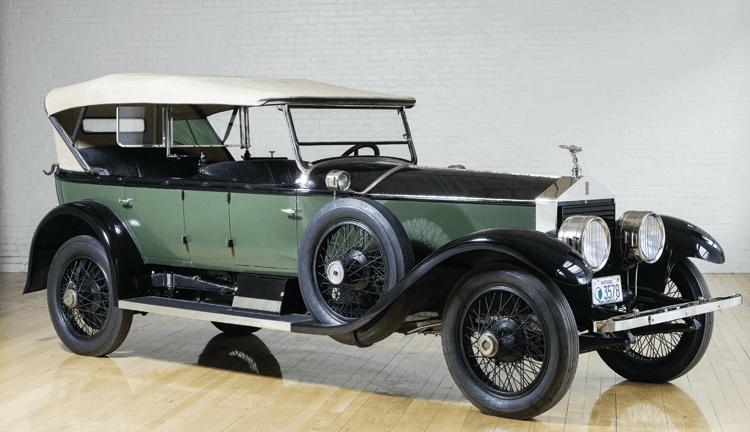

Also acquired from his father was Ruger’s early affinity for classic cars and all things mechanical. His passion for cars began with the restoration of a 1933 Buick engine at age twelve. At age fourteen, young Ruger bought a 1924 American-LaFrance fire engine and restored the engine himself. He has since driven it many happy miles. “I had it completely restored cosmetically about ten years ago. It remains quite gorgeous and very much like an old friend,” he says.

- The most imposing features of the west end of the gallery are the grand fireplace with mantel and the 1877 Steinway piano with rosewood case, a late example of the “square grand” form. Often played by some of Ruger’s friends, he added an electro-mechanical player to broaden its entertainment possibilities.

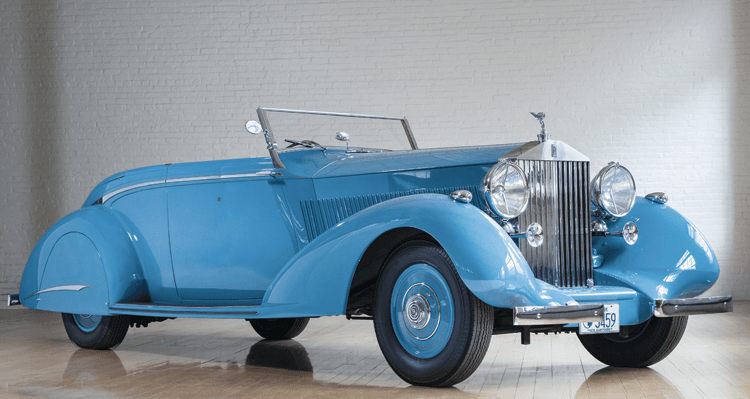

At one time Ruger had more than forty-five vintage vehicles. In order to purchase his first house, he sold a couple of Rolls Royces and Bentleys. In the 1980s, he resumed collecting, thoughtfully curating the collection so that he now has twenty classic cars, fire engines, and motorcycles, including a 1925 Rolls Royce Silver Ghost, three American-LaFrance fire engines, a 1924 and 1939 Packard, a Pierce Arrow, a rare four door Oldsmobile convertible, and a 1923 Stanley Steamer, the oldest of his cars. The premier vehicle in his automobile collection is a turquoise blue 1937 Rolls Royce Phantom III Thrupp & Maberly Drophead Coupe built for the last Maharaja of Darbanga, India. It has a unique disappearing top and Sports Torpedo Cabriolet coachwork. In 2012, it was winner in its class at the Pebble Beach Concours de Elegance in California.

Unlike some collectors who admire their prized possessions passively, Ruger uses his. Last summer, for instance, he toured the vicinity of Stowe, Vermont, in his Stanley Steamer, covering 100–125 miles a day. The course followed secondary and dirt roads similar to the type of road traversed when these cars were first built. “It makes you think it could be 1920 as you drive along past barns and silos, stonewalls, and farm houses. It’s very much like being transported away from modern influences,” says Ruger.

The quest for great cars, furniture, or artwork all involves research, restoration, and appreciation. When asked which pieces are his favorites, Ruger instantly responds, “All of them.”

Originally published in the Summer 2014 issue of Antiques & Fine Art magazine in tandem with InCollect.com. A digitized version of the entire issue is available on www.afamag.com.