Havana Modern

The development of modern architecture in Cuba occurred during the first half of the twentieth century, and it was during those years that Cuba accomplished its most unprecedented achievements in both civic and domestic architecture. What is most surprising is that even though Havana has examples of every Western architectural style that exists from the past five hundred years (and many of the Western Hemisphere’s most important monuments from previous centuries), the largest part of Cuba’s capital city was built in the sixty years from independence in 1902 to the mid-twentieth-century revolution in 1959.

Cuba’s early to mid-twentieth-century modern architecture movement can be seen as having two major phases. The first began a few years before World War I and continued to World War II. While it paid homage to Beaux-Arts influences with eclectic Cuban interruptions, it also formulated and developed new design ideas that were expressions of the ever-increasing interest in American engineering techniques and architectural trends. The second phase lasted from World War II to the mid-1960s and, under the impact of rectilinear cubism, emphasized the theories of modernist architects such as, notably, Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, Frank Lloyd Wright, Walter Gropius, and Le Corbusier, the high priest of the genre. By the late 1950s Cuba’s modern movement had reached maturity and ushered in a mature International Style and an assimilation of a repertory of modern regionalist forms. The climax came with the 1959 revolution’s political realignment, which culminated in the closing of Havana’s School of Architecture in 1965.

Havana was Cuba’s center of learning, culture, and architectural experimentation. Regardless of the proliferation of new wealth and construction, much of the earliest twentieth-century architecture was stylistically transitional and continued to pay at least partial allegiance to the historic colonial models and neoclassicism of the previous century. Reconciliation between urban architects who considered themselves early modernists and those who still thought of themselves as traditionalists resulted in a surprising outpouring of architectural styles that became known as Cuban Eclecticism. The island’s leading architects of the day, such as Leonardo Morales, Raúl Otero, Evelio Govantes, Félix Cabarrocas, and Eugenio Rayneri, practiced Cuban Eclecticism. Essentially a “battle of styles,” with every variation of architectural trend that was at the time considered a matter of fashion, was tried or incorporated in residential design, and because of this variety, Havana’s residential architecture was said to be “splendidly encyclopedic.”

- In the first half of the twentieth century the influence of modern American architecture on Havana was most prominent in the construction of the city’s banks, apartment towers, hotels, warehouses, and public buildings, the most famous of which is the Bacardí Building. Completed in 1930, its style moderne decorative surface motifs strongly integrated with the edifice’s interior decor. The Bacardí Building was the headquarters of the Bacardí rum empire. A bronze bat, a Cuban good luck emblem and the logo of the Bacardí firm, crowns the building’s ziggurat-profiled top spire.

Cubans had experienced four centuries of Spanish colonial rule, which ended after Cuba’s third uprising against the crown since 1868, the War of Independence (1895–1898). The actual birth of Cuban independence was delayed for another four years (1898–1902) by the first of two U.S. military occupations of the island. The wars had virtually paralyzed any large-scale construction for decades, and the Cuban republic was faced with the challenging task of forging a new national cultural identity, one based on a more modern civil society.

Although Havana’s School of Arts and Sciences (Facultad de Letras y Ciencias) added curricula in civil engineering, electrical engineering, and architecture in 1900, the advent of the twentieth century did not bring immediate or radical changes in architecture or interior design; rather, there was a transitional period that clung to late nineteenth-century styles, which included neoclassicism, neocolonialism, and a peninsular Beaux-Arts eclecticism. Derived from the academic teaching of the world center for architectural education, the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris, Beaux-Arts architecture typically embraced the styles of antiquity, the Renaissance, and seventeenth- and eighteenth-century France.

Eventually the spread of technology, industrialism, and a desire for the latest in domestic conveniences, together with political, economic, and social changes, launched a new phase of modernity in Havana’s architecture. European and American tastes and ideas embodied the highest aspirations of the twentieth-century modern era and started to infiltrate and influence Cuban architectural education. It also began to liberate Cuban architecture students from the bondage of École des Beaux-Arts teachings. Over time, Beaux-Arts style became less popular and the theories of functionalism, in which form follows function, emerged, spawning a demand for more modernity in domestic as well as civic architecture.

Among the half a million immigrants who arrived in Cuba during the first quarter of the twentieth century were architects, artisans, builders, and sculptors who had been trained and who had cultivated their trades, talents, and tastes under the mantle of the European modern movement. The newest fashion in design, specifically the Art Nouveau style, arrived from Europe and flourished, especially in Havana, with Catalan, Viennese, Belgian, and French versions in overlapping successions.

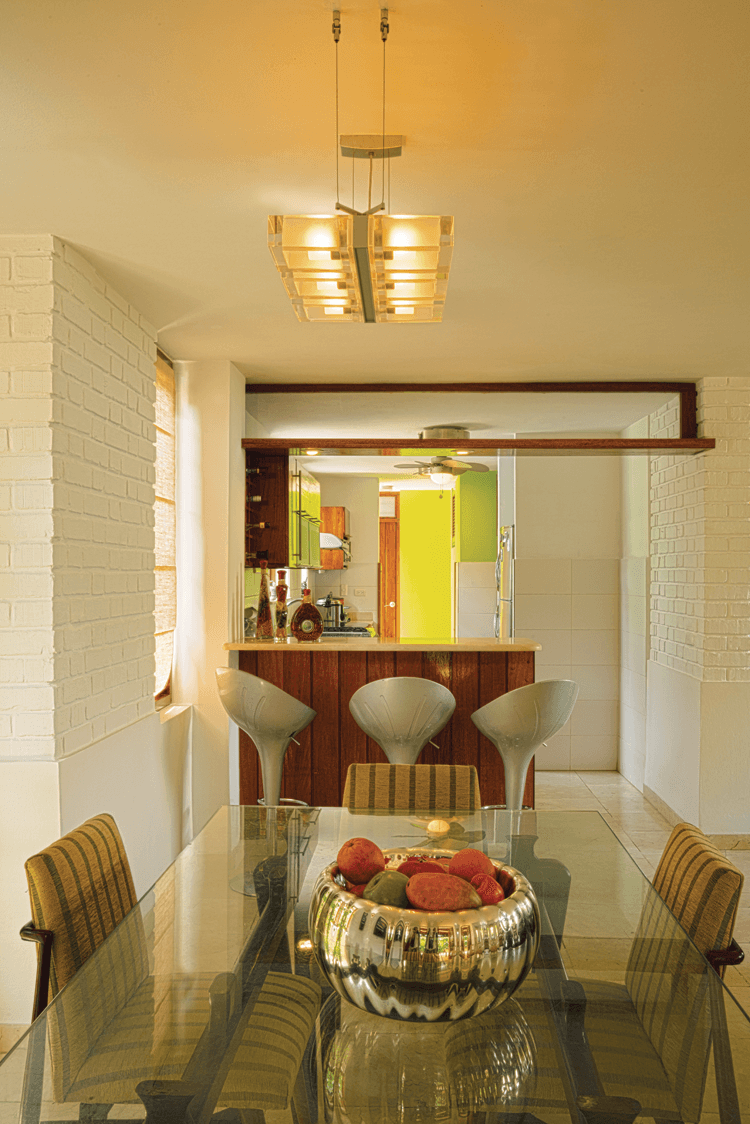

- The Maria de los Dolores Puig house was designed by Mario Romañach and completed in 1955. Although modest in scale, it is typical Romañach in the use of bare bricks and a hidden side entrance. Most of Romañach’s architecture has maturity and confidence somewhat lacking in the work of his Cuban contemporaries.

Art Nouveau, known as modernismo in Spanish and modernista in Catalan, is considered a key element in the beginning of the modern movement in Cuba insofar as it rejected the previous decades’ classical historicism and the eclectic revival styles of the island’s architecture and decorative fashions. Art Nouveau’s popular ornamental and decorative motifs were based on nature and the sensuous, swooping organic curvilinear forms of flowers and plants. The style informed design in masonry, carpentry, stained glass, metalwork, and furniture.

An emanation of and a modernist reaction against the fashionable Art Nouveau style and its gratuitous ornament was referred to as the “new art”—since termed Art Deco—a style generally describing design between the two world wars. The cleaner-lined Art Deco style, or style moderne, as it was called at the time, was associated with a wide variety of decorative arts and luxury works produced during the interwar years. Numerous residential and public buildings in Havana adopted Art Deco aesthetics, ornaments, and decorations in their designs.

The Art Deco style was soon embellished upon, and streamline modern emerged. Streamline was popular in Havana for its blend of modernism, post-Depression pragmatism, and industrial design. Concurrent with this fashion was modern classicism, modern regionalism, and the beginnings of the International Style.

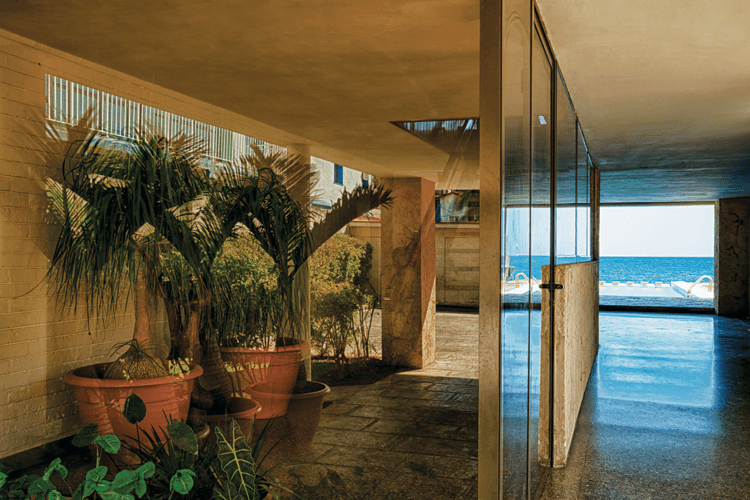

- Architect Miguel Gastón, built this house overlooking the ocean in Miramar in 1952 for himself. Built on Le Corbusier-style pilotis, the elevated second floor contains all the main rooms, leaving the ground floor available for an open porch, carport, and saltwater swimming pool—a design that proves advantageous during hurricane season because of flooding.

By the mid- to late 1940s Cuba had recurring and extended periods of economic prosperity. The island’s newest architecture, now devoid of the reminders of its past colonial baroque, Mudejar, Renaissance, and Beaux-Arts traditions, began to identify itself with the International Style, which disseminated from Europe via the United States. Thanks to the capital investment that continued to accumulate in Cuba after World War II, Havana experienced a second twentieth-century housing boom. Famous architects from around the world such as Walter Gropius, Mies van der Rohe, José Luis Sert, Franco Albini, Richard Neutra, and Philip Johnson visited Cuba, and their influence led to many International Style buildings, characterized by clean, rectilinear designs. (Both Johnson and Mies van der Rohe designed buildings for Havana that, unfortunately, were never realized.)

The International Style’s geometric shapes and bare-of-ornament characteristics gave sections of Havana’s modernist urban landscape the silhouette of shoeboxes on end. The search for new ideas in both architecture and urban planning and the technological developments of reinforced concrete, glass, and steel frames brought about a boom in the development of apartment buildings—especially for the middle classes—starting in the 1940s and continuing through the next decade. As the late Cuban historian Maria Luisa Lobo Montalvo writes, “With regard to individual housing and apartment buildings alike, two distinct architectural trends emerged: one, which we may call ‘modern,’ embraced new criteria of spatial distribution and functional use, but remained ultimately anodyne and expressionless. The other was more properly ‘avant-garde,’ and sought to generate space on the basis of function. It achieved genuine heights of architectural merit by incorporating certain values of our national culture to synthesize a uniquely Cuban architecture….” 1

Havana’s modernity came into its glory and peaked in the 1950s, when the city’s transit tunnels, large-scale hotels, airport, and modern civic center were built. Thousands of homes were designed in the new modern tradition, inherited from the Cuban upper-class architecture that dictated the fashions and was destined to become the style of the petite bourgeoisie.2 Through “cultural seepage”—that which translates the new into the popular—these homes were interpretive modernist designs built in a contemporary fashion but on a much smaller scale in the suburbs of Havana and in cities and towns throughout the island. Of course, other architectural trends surfaced in the 1950s, including modern regionalism, as seen in works by architects Ricardo Porro, Emilio del Junco, Max Borges Jr., and Mario Romañach, all of whom renewed selective colonial traditions and elements within the scope of modernism.

Although the 1959 revolution did not immediately cause a complete break with Cuba’s modern architecture movement, more than two-thirds of Cuba’s successful professional architects elected to leave the island. The substantive end came with the Cuban government’s order in 1965 to abandon construction of the partially built National Schools of Art because of ideology. This marked a shift of focus in the direction of low-cost prefabricated housing and eventually a Soviet-style “brutalism” of rough, exposed concrete surfaces.

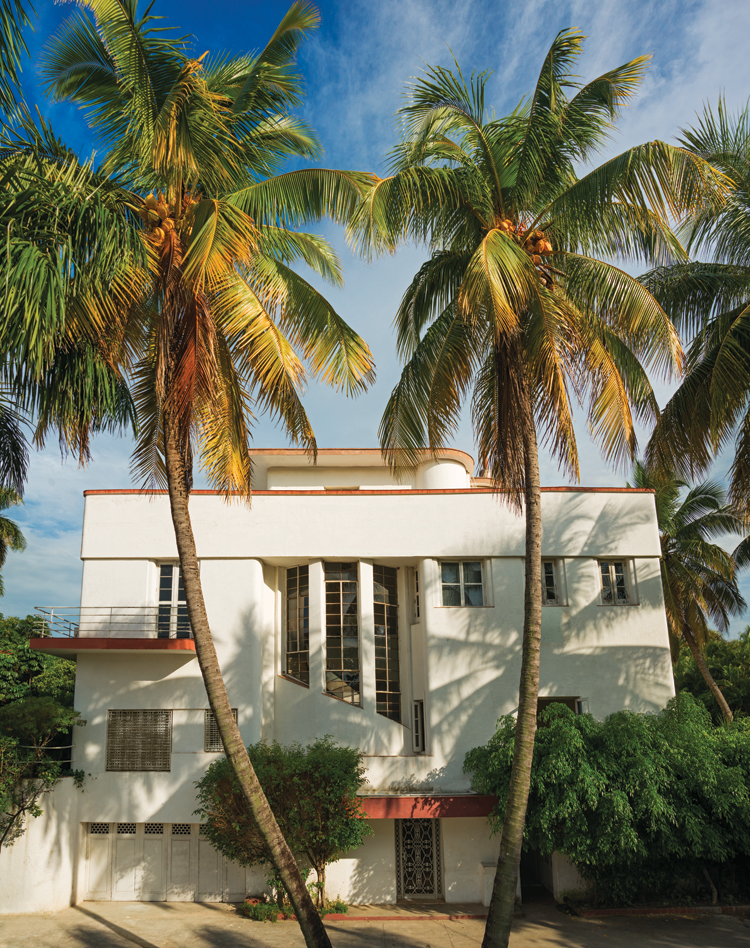

- The house of Timothy James Ennis was designed by Ricardo Porro and built in 1957. It displays strong Le Corbusier influence and is the last private residence Porro built in Cuba. The Ennis house is an example of organic expression that follows the styles of modernism and postmodernism, especially in the handling of surfaces and space.

Michael Connors is the author of numerous books on the architecture, interiors, and history of the Caribbean, British West Indies, and Cuba.

This article was originally published in the Winter 2014 issue of Antiques & Fine Art magazine, a digitized version of which is available on afamag.com. InCollect.com is a division of Antiques & Fine Art, AFAnews, and AFA Publishing.

2. Ricardo Porro, “Vila Villegas, La Havane,“ in L’archtectura d’aujourd’hui. No. 350 (Jan./Feb. 2–4): 71.