Images of the American People

Small Portraits from 1820 to 1850

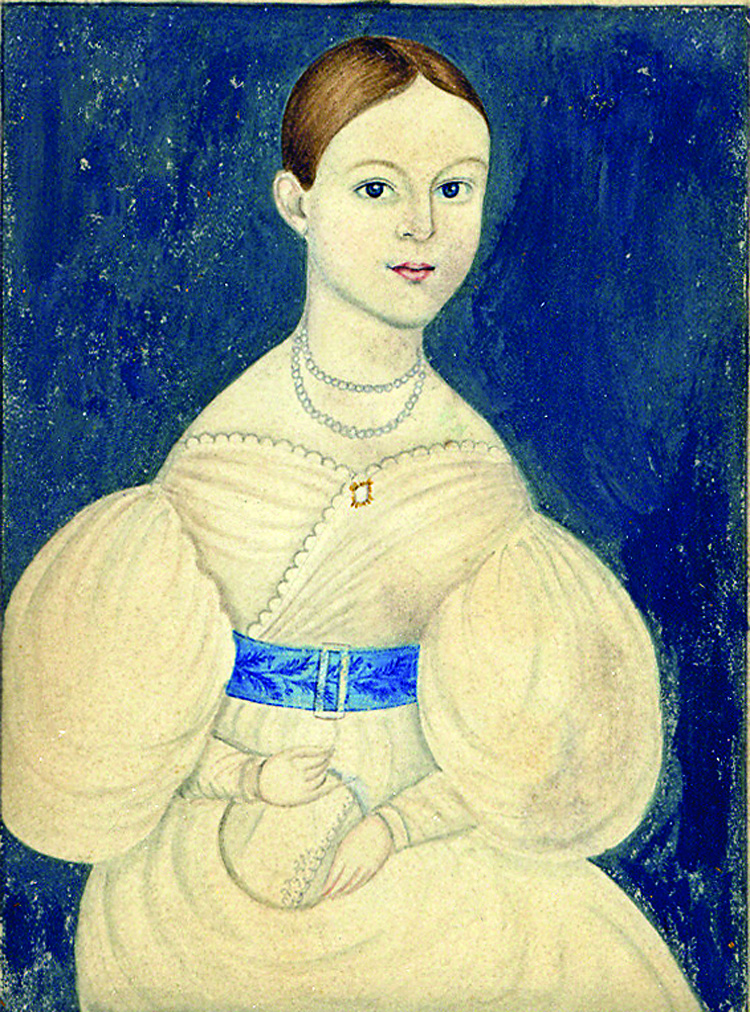

Walk into almost any American antiques show and you will find for sale several examples of a unique portrait style produced in the northeastern United States from approximately 1820 to 1850. These portraits measure only about 3 by 2¾ to 5 by 4 inches, and present the sitter in a tightly cropped image on either a light white cardboard called Bristol board or on paper. In a direct pose, watercolor, ink, or pencil is used to depict the sitter in bold relief using an economy of line. Unwavering light is directed straight onto the sitter without shadow, so the figure appears to be almost self-illuminated. Facial features range from examples left roughly sketched to those minutely finished with delicate color. The sitters are solitary, with emotion and gesturing conspicuously eliminated and, usually, there is no attempt to use background detail to produce an atmospheric space. In a monumental stillness, the sitters seem to be fixed in time with the image so close to the picture plane that the person appears ready to step into the viewer’s world.

Before photography became commonplace, these likenesses were the dominant portrait style in America. Though absent from American art history textbooks, vast quantities of these small portraits were painted by numerous professional artists. Produced in both rural towns and major cities, the importance of these small portraits to the average American was profound and represented the democratization of American art.

This portrait genre has no specific name. Though often called “folk art miniatures,” today the word “miniature” is primarily used to denote a portrait on ivory, which requires different painting techniques, and the term “folk art” fails to adequately describe this style of distinctive portraits. We prefer the term “small portraits.”

What was the impetus behind this new approach to portraiture? As French visitor Alexis de Tocqueville observed when touring the country in 1831 and 1832, “[Americans] may amuse themselves for a while with considering the production of nature, but they are excited in reality only by a survey of themselves.” Oil on canvas portraits, typically measuring about 30 by 25 inches, were intended to dominate parlor walls, displaying the sitter’s gentility and position. These were affordable only to the wealthier spectrum of society. Academic portrait painters often asked $60 to $100, and even non-academic “folk” artists charged between $15 and $30. Miniature portraits on costly ivory generally started at $8. For the average American, small portraits, with prices ranging between $1 and $4, were an affordable alternative. It was not unusual for entire families to have their individual portraits made at the same time. They were the only means ordinary Americans had to preserve an image of themselves and their loved ones. Yet, it was not price alone that gave these small portraits such mass appeal.

Small portraits were novel in terms of the image presented, painting materials used, and the information conveyed about the sitter. A portrait’s small size demanded a close examination that created an intimate personal exchange with the viewer. Additionally, these portraits could be mounted in lockets and worn around the neck, keeping loved ones forever close. They fulfilled a need for sentimental remembrance.

During the 1820s, increased domestic manufacturing made artist’s paints, papers, and brushes more readily available and less expensive. By 1824, in Philadelphia, G. W. Osborne began the commercial production of dried watercolor cakes for the first time in America. These just had to be mixed with water, so artists no longer had to hand grind their pigments.1 Not previously considered appropriate for serious art, small-portrait artists embraced this colorful and painterly media, which allowed a freedom and fluidity previously produced with ink or pencil. Indeed, many small portrait artists simply used pencil, while others combined watercolor, ink, and pencil.

Small portraits also reflected a major transition in how Americans saw facial features as a way to understand an individual’s character. Beginning in the late eighteenth century, the popular theories of physiognomy stated that a person’s character could be read from the facial outline.2 Silhouettes, depicting just the sitter’s profile, became immensely popular and were produced in huge numbers.

Starting in the early 1820s, the new ideas of phrenology, the analysis of a person’s character from an examination of the face and head, gained popularity in America. This initiated a national mania for examining the bumps and shapes of people’s heads to interpret their personality, talents, and health, even suggesting suitable occupations and describing qualities of complimentary potential spouses. A British traveler, Harriet Martineau, remarked that after hearing a phrenology lecture “the great mass of [American] society became phrenologists in a day.”

These ideas also affected artists and their sitters. Small portraits, with their full or side views of the face, provided images that could be examined for a sense of the sitter’s character and living presence. This explains why these portraits do not show emotions or even a smile on the sitter’s face. Instead, they provided an image that revealed the deeper parts of the sitter’s personality that could be read through phrenology. Today, we have to struggle to understand the underlying phrenological meanings that were part of the expressive power of these portraits when they were created.

Americans from all walks of life eagerly sought these small portraits, and numerous artists specialized in their production. Most of the artists were itinerants who found commissions by travelling between cities and small towns. Today, we know the names of many of these artists and the few who have been studied in depth describe the rich cultural and aesthetic heritage that these small portraits fostered.

There were many reasons for becoming a small portrait painter. Economic necessity led Justus Da Lee (1793–1878) to become a professional artist as he was approaching forty years of age (Fig. 1). During the 1820s and early 1830s, he rented a small farm in Cambridge, New York, taught in the local public school, and his household produced significant quantities of homespun textiles for sale.3 Teachers were poorly paid and the new American textile mills and less expensive English imports eliminated the once important homespun industry. Letters between members of the Da Lee family reveal that small portrait production was actually a family enterprise. The letters describe Justus’ younger brother Richard and his son Amon travelling together as itinerants and Justus and Amon working together on the same portrait. On a trip to Utica, New York, during 1839, Justus distributed advertising cards in doorways and returned the next day to show samples. Portraits were $3 for a single or $2.50 each for a couple or family. Each portrait required one or two hours of work, but he kept them several additional days for further embellishment “being determined to give the very best satisfaction.” Working together, the Da Lee family members produced portraits in a remarkably similar style.

James Guild (1797–1844) kept a diary from 1818 to 1824, which begins in Tunbridge, Vermont, at age twenty one. After having been an indentured servant since age nine, Guild was determined not to be a farmer and tried various professions before he met a local painter, Edwin W. Goodwin, in Canandaigua, New York. Guild “asked him what he would show me one day for, how to distinguish the coulers [sic] & he said $5, and I consented to it and began to paint.” Guild then stopped by every house he passed and inquired if they wanted a portrait, with the provision that they need not pay if it was unsatisfactory. After three days, he received one dollar for a portrait and considered himself “quite a painter” (Fig. 2). He then moved throughout eastern New York and Vermont searching for portrait commissions. Guild’s diary presents a vivid picture of the loneliness and difficulties of the itinerant artist.4

Several artists produced small portraits in a variety of styles so that they could offer a range of prices to suit every pocketbook. James Henry Gillespie (1793–after 1849) was an English artist who began a decade-long itinerancy in 1832 along the East Coast of the United States with stops in the major cities of Maine, Massachusetts, New York, Maryland, and Pennsylvania.5 He produced portraits in at least six different styles, with prices ranging between 25 cents and $4 for simple silhouettes to carefully finished small portraits in full color. Based on the large numbers found today, Gillespie’s most expensive full-color small portrait appears to have been his most popular (Fig. 3). Initially costing $2 in Maine, by the end of his American itinerancy, he was charging $4 in Baltimore.

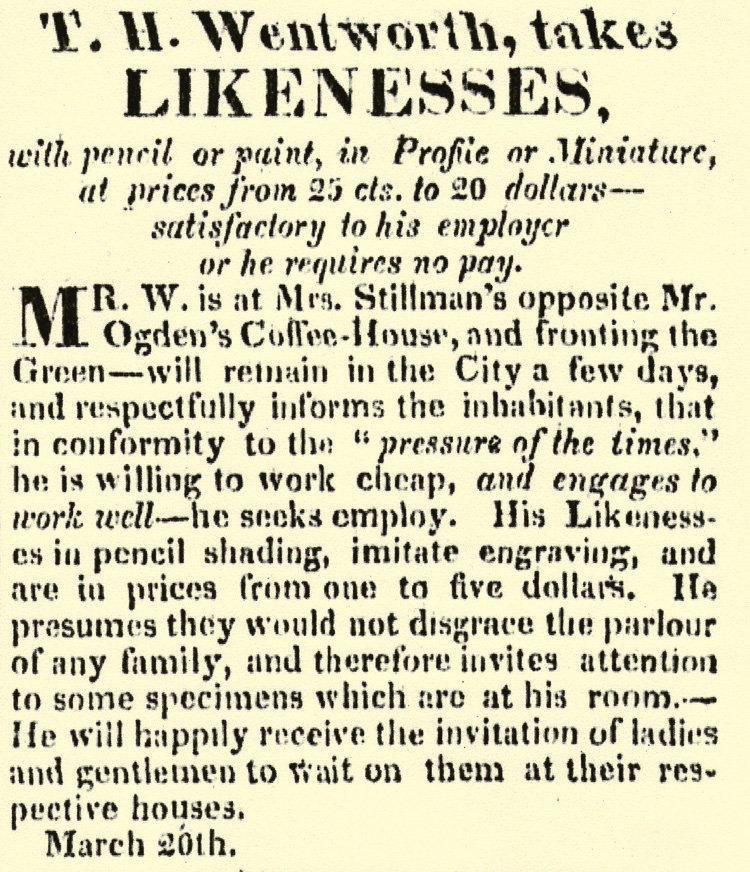

Some artists produced not only small portraits, but any other type preferred by the sitter. In the 1820s, Thomas Hanford Wentworth (1781–1849) traveled throughout Connecticut, New York, and Massachusetts, taking “likenesses at any price that may be desired” (Fig. 4), with portraits from 25 cents to $20 for an oil on canvas painting, and small pencil portraits from $1 to $5. Born in Norwalk, Connecticut, as a young man he moved to England, where he began taking silhouettes, returning home in 1806.6 He occasionally numbered the portraits, with 3,243 noted on the back of one example, providing a glimpse into his productivity. Additionally, he patented and sold a cooking stove, provided art instruction at Sarah Pierce’s Litchfield Female Academy in Connecticut while working on portrait commissions in Litchfield (Fig. 5), and found a ready market for his views of Niagara Falls.

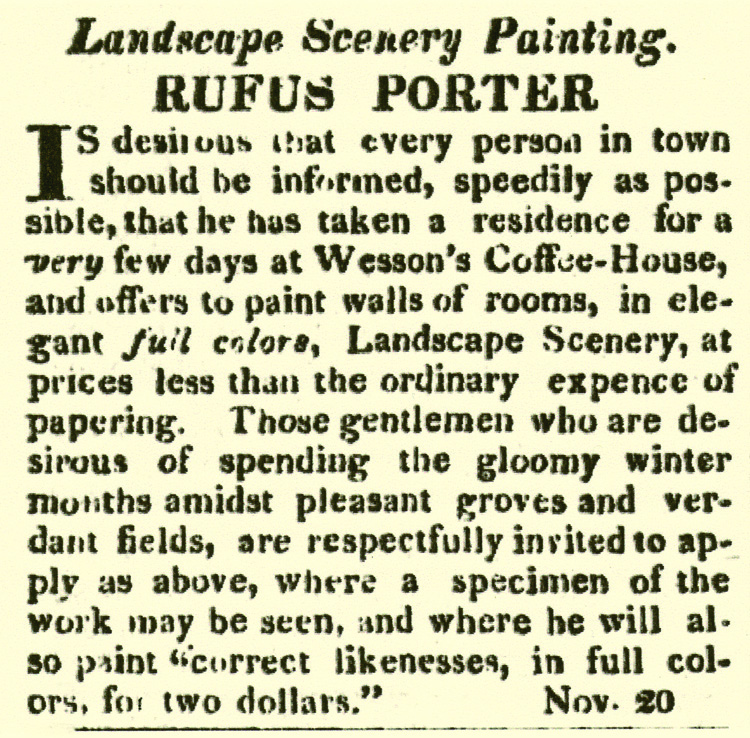

For some artists, producing small portraits was just one of their accomplishments. Rufus Porter (1792–1884), was a quintessential Yankee whose contributions ranged from the artistic to the scientific.7 He advertised silhouettes for 20 cents, side view portraits in full color for $1 or $2, frontal poses at $3, and miniatures on ivory for $8 (Fig. 6). He also used both freehand and stencil techniques to paint fanciful fresco murals of American landscapes on the plaster walls of New England homes (Fig. 7). In 1845, Porter founded Scientific American, which he filled with practical art instruction along with enthusiastic advice for the inventor. Porter’s own inventions included a steam-carriage expected to reach speeds of ten miles per hour, portable fences, and a steam-powered dirigible capable of taking one hundred passengers from New York to California in three days—all completely impractical during his lifetime. The flamboyance of Porter’s life adds to the allure of his small portraits.

Several artists developed quirky styles that make their small portraits readily identifiable. James Sanford Ellsworth (ca. 1802/3–1874) painted stoic New Englanders who appear to be floating on heavenly clouds (Fig. 8). Sometimes the sitter is posed on strange, fanciful chairs that wrap around the figure.8

Many of the small portraits found today are signed by or can be attributed to artists, though the details of their lives remain elusive. Maria Davenport produced especially colorful images (Fig. 9). B. Loves included a colored banner below the sitter inscribed with the subject’s name, age, and date of the portrait (Fig. 10), and often signed the reverse of his portraits so hastily the artist’s name has been interpreted several ways. Amos M. Holbrook and “Jenks” both used flat white paint to oddly accentuate the face (Figs. 11, 12).

J. M. Crowley combined art instruction with the production of small portraits executed in pencil. Raised in Newark, New Jersey, Crowley spent his career moving and re-establishing his drawing school every few years in the major East Coast cities (Fig. 13).9 Wonderful examples of the genre by still anonymous artists continue to be regularly found (Fig. 14).

From approximately 1820 to 1850, small portraits were a major aspect of America’s artistic accomplishment. Capturing the endearing likenesses of the family, they were the portraits of the heart for the average American. Starting in the early 1840s, small portraits were replaced by daguerreotypes, which provided images that were novel, less expensive, and more precise. Soon, the era of the small portrait ended and the local small portrait painter and constant flow of itinerants through every village disappeared. A portrait painted by a professional artist again became a high priced luxury item meant to prominently display the sitter’s status. American portrait painters were never again to have such an accepted and understood position in the everyday life of the average American. Today these small portraits offer us a remarkable glimpse of how a generation of Americans and their loved ones wished to be remembered.

Suzanne Rudnick Payne, Ph.D., and Michael R. Payne, Ph.D., research early American folk artists and are members of the American Folk Art Society. This is the ninth article they have published on early American artists.

2. Ellen G. Miles, Saint-Memin and the Neoclassical Profile Portrait in America, (Washington: National Portrait Gallery and the Smithsonian Institution Press, 1994), 44-59.

3. Suzanne Rudnick Payne and Michael R. Payne, “To Please The Eye: Justus Da Lee and His Family,” Folk Art, vol. 29, no. 4 (Winter 2004-2005): 46–57; the New York State Census, 1825 and 1835; and Joan R. Brownstein and Elle Shushan, “Side Portrait Painters: Differentiating the Da Lee Family Artists,” The Magazine Antiques (July/August, 2011): 154-161.

4. Arthur Kern and Sybil Kern, “James Guild Quintessential Itinerant Portrait Painter,” The Clarion, (Summer 1992): 48–57; and Arthur W. Peach, ed., From Tunbridge, Vermont to London England—The Journal of James Guild, Peddler, Tinker, Schoolmaster, Portrait Painter from 1818 to 1824,

vol. V, no. 3 (Montpelier: Proceedings of the Vermont Historical Society, September 1937): 249–314.

5. Suzanne Rudnick Payne and Michael R. Payne, “Six Choices for the Sitter-James H. Gillespie (1793–after 1849),” Antiques and Fine Art, vol. 8, no. 6 (Summer/Autumn 2008): 200–205. We provide here new information that James H. Gillespie’s middle name was Henry, he was born in Perth, Scotland, married Louisa Temple of London, and had two children. His son, James, who was a tailor, appears to havebeen with the artist while he resided in Boston.

6. Arthur Kern and Sybil Kern, “Thomas Hanford Wentworth: Little-Known Early American Limner,” Folk Art, vol. 27, no. 3 (Fall 2002): 54–61.

7. Jean Lipman, Rufus Porter Yankee Pioneer, (New York: Clarkson N. Potter, 1968); and Deborah M. Child, “Thank Goodness for Granny Notes: Rufus Porter and His New England Sitters,” Antiques and Fine Art, vol. 10, no. 4 (Summer/Autumn 2010): 190–195.

8. Lucy B. Mitchell, “James Sanford Ellsworth 1802/3–1874,” American Folk Painters of Three Centuries, Jean Lipman and Tom Armstrong, editors (New York: Hudson Press, 1980), 70–73.

9. Michael R. Payne and Suzanne Rudnick Payne,manuscript in preparation.