In Plain Sight: Discovering the Furniture of Nathaniel Gould

Research by Kemble Widmer and Joyce King

This archive article was originally published in the Winter 2014 issue of Antiques & Fine Art magazine.

Historians have been studying Massachusetts colonial furniture for more than a century, yet the 2006 “discovery” of three business ledgers kept by Salem cabinetmaker Nathaniel Gould (1734–1781) reminds us of how far we still have to go to fully understand this important craft and its rich history. Gould had been a shadowy figure, little more than a name on a list of craftsmen active in the town in 1762.1 In 1983, when curator Morrison Heckscher noticed Gould’s signature on the much admired desk-and-bookcase in the collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art (Fig. 1), interest grew, but its authenticity was questioned because it was followed by the words “not his work” (Fig. 2). This ambiguity led at least one historian to attribute the monumental desk to another Salem cabinetmaker.2

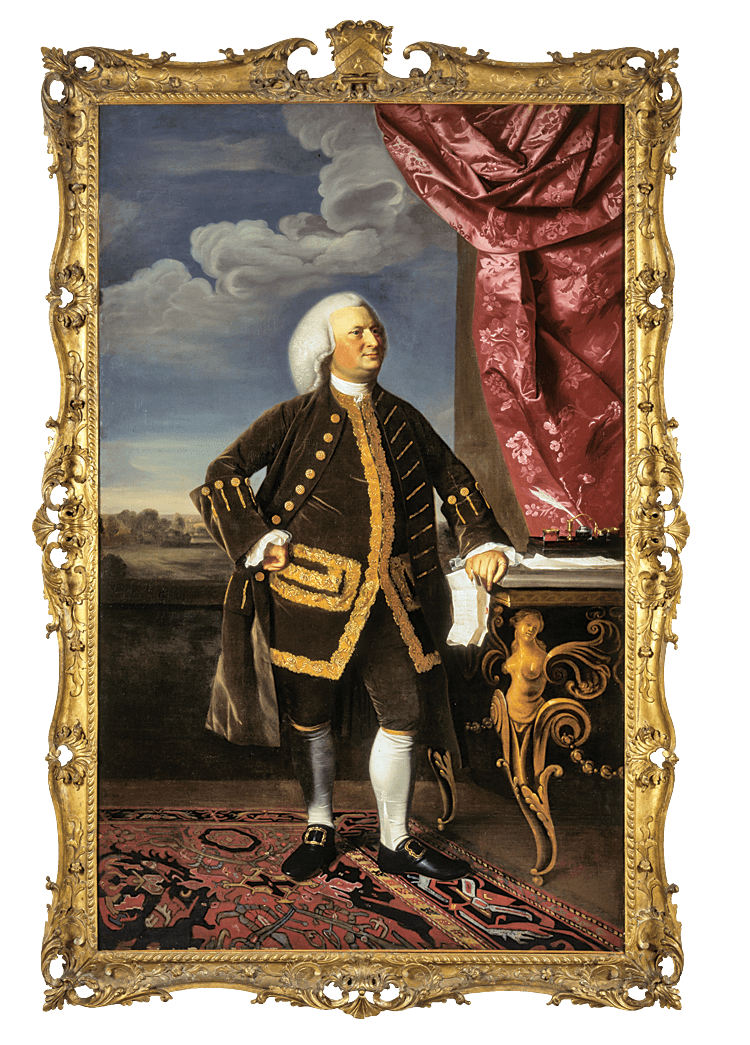

Gould’s ledgers were given to the Massachusetts Historical Society (MHS) in 1834 by Nathan Dane of Beverly, the lawyer who settled Gould’s estate in 1781. In 2006, a citation for them posted online by MHS for the first time was noticed by Joyce King and Kemble Widmer II, leading them to become the first furniture historians to examine the documents. They quickly realized the two day books and an account book constituted the most complete business records known for a New England eighteenth-century cabinetmaking shop. Kept between 1758 and 1783, the ledger entries document the production of almost three thousand pieces of furniture for some five hundred different clients. Among them were many of the leading merchants in the Salem region, such as Jeremiah Lee of Marblehead, then the richest man in the Bay colony (Fig. 3). Gould was clearly the region’s premier cabinetmaker.

In Plain Sight: Discovering the Furniture of Nathaniel Gould is the Peabody Essex Museum’s retrospective look at a selection of known furniture made in or associated with the Gould shop, including chairs, tables, and a variety of case forms. The exhibition is accompanied by a major publication based on the extensive research conducted by Widmer, King, and Elisabeth Garret Widmer, exploring many aspects of Gould’s furniture production, including design sources, business practices, journeymen, and clients. Three additional essays by noted historians provide a broader cultural context for understanding Gould’s work. It also contains, in a series of appendices, a full transcription of the ledger entries, which will be of enormous value for future research, not only on Gould furniture, but also the social and cultural life of Salem.

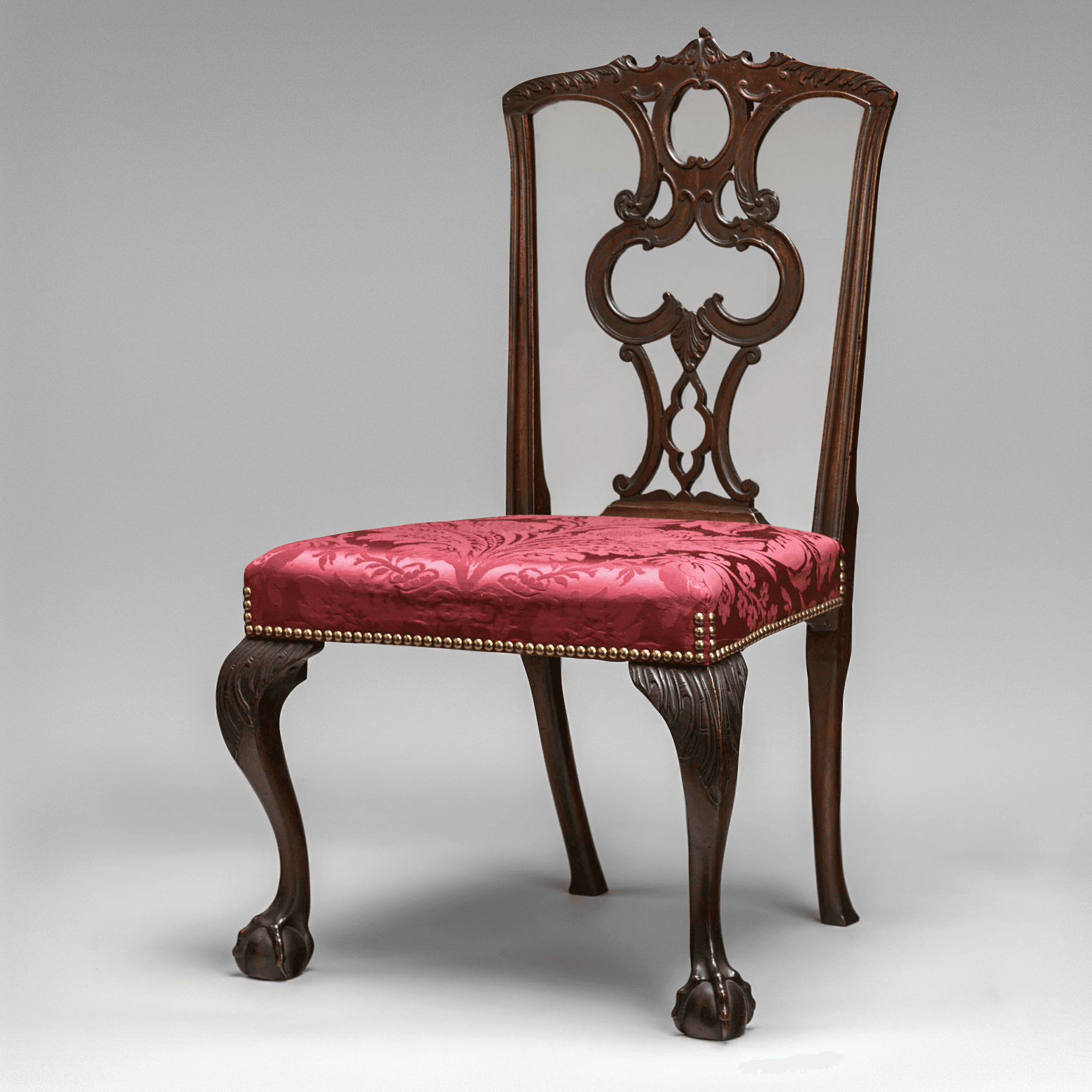

After gleaning a wealth of information from the ledgers, King and the Widmers set out to locate examples of his furniture through genealogical research linking account book entries with the provenance of surviving pieces of furniture in public and private collections. The pair of richly carved side chairs in the Metropolitan Museum for example, long unattributed, has a history of descent in the Benjamin Pickman family of Salem (Fig. 4). The team was able to link the chairs to the August 24, 1770, entry in Gould’s account book for a set of eight carved chairs ordered by Clarke Gayton Pickman of Salem following his marriage to Sara Orne.

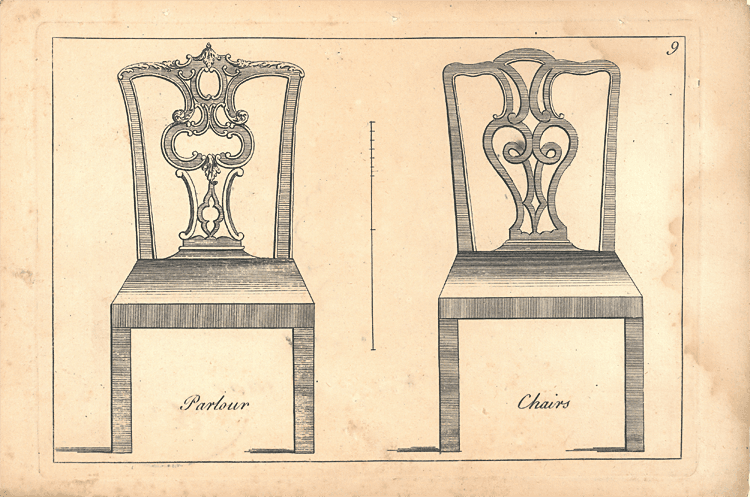

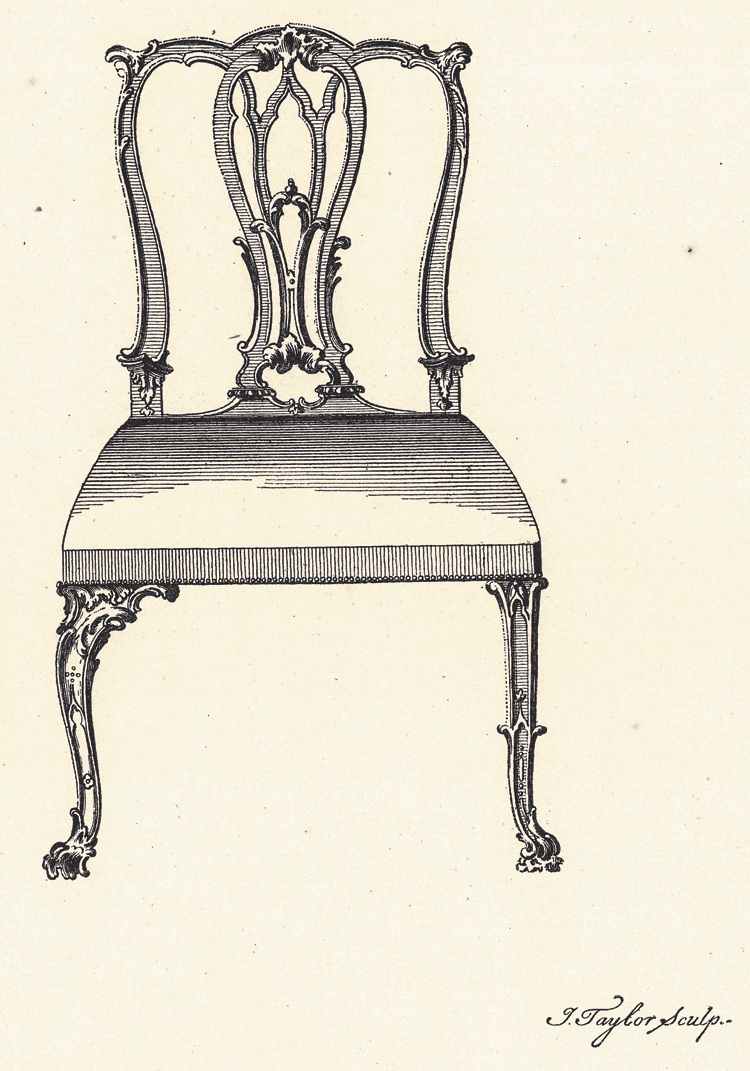

The distinct open-double c-scroll splat on these chairs was copied from a chair design published in London in 1765 by Robert Manwaring (Fig. 5). A copy of the design in the Phillips Library at Peabody Essex Museum, believed to be the copy owned by Gould, has an ink inscription on the back of plate 9 stating “From London 1762,” which suggests Gould owned at least one plate of Manwaring’s Cabinet and Chair-Maker’s Real Friend and Companion well ahead of publication date. He is the only known American chair maker to use this distinct pattern. He also owned a copy of the 1762 edition of Thomas Chippendale’s influential The Gentleman and Cabinet-Maker’s Director, which is listed in the inventory of Gould’s estate. Both of these design sources suggest Gould was keen on keeping pace with current London fashions, an assumption verified by a chair from his shop in the collection of the Winterthur Museum (Fig. 6), which is the only Massachusetts chair to faithfully copy a Chippendale chair design (Fig. 7).

Gould also mastered the fashionable bombé form during his career, evidenced by comparing two chests of drawers done at different times. The earlier example made about 1760 (Fig. 8), is less successful than one done about 1781 (Fig. 9). In the latter, he improved the overall proportion by increasing the height of the drawers and width of the top to match the width of the bombé sides. He also started the curve of the side at the second drawer to eliminate the sharp transition between the straight upper drawers and the curve of the lower drawers seen in the earlier piece.

- Fig. 8: Attributed to the shop of Nathaniel Gould, Bombé Chest of Drawers, 1758–1766. Mahogany and white pine. H. 38⅜, W. 415⁄16, D. 205⁄16 inches.

Courtesy Marblehead Museum and Historical Society, Marblehead, Massachusetts: Gift of Mrs. Francis B. Crowninshield.

Photography by Dennis Helmar Photography; © 2014 Peabody Essex Museum.

The account books also revealed that 45 percent of Gould’s domestic furniture production was to fill wedding orders, a previously unknown pattern of conspicuous consumption. The size of many of these wedding orders is truly impressive, suggesting the sons and daughters of the privileged merchant class were trying to outdo one another when furnishing their first home, all usually paid for by their parents. When Lois Orne married Dr. William Paine of Worcester in 1773, the couple received thirty-seven pieces of new furniture costing just over £120. They received four sets of chairs, seven tables of various sizes and designs, two bedsteads, a desk, and three case pieces for the bedchambers, including the most expensive item, a chest-on-chest, now in a private collection (Fig. 10). Other household items were also acquired when setting up a home; the Paines received numerous pieces of silver table wares made by Paul Revere of Boston, the largest single order of his career, now preserved at the Worcester Art Museum.

Several of the wedding orders also included a desk-and-bookcase, the most expensive item produced by the shop. The Metropolitan’s desk (fig. 1) was ordered by Jeremiah Lee in April 1775 for his new son-in-law Nathaniel Tracy of Newburyport at the time of his marriage to Lee’s daughter Mary. The impressive block-front of the lower case replaced the bombé form as the most fashionable design statement after 1770. Gould was also the major importer of mahogany into Salem, so he was able to retain the best pieces for his most important clients, evident in the dense, close-grained and richly colored wood used to make this exceptional piece.

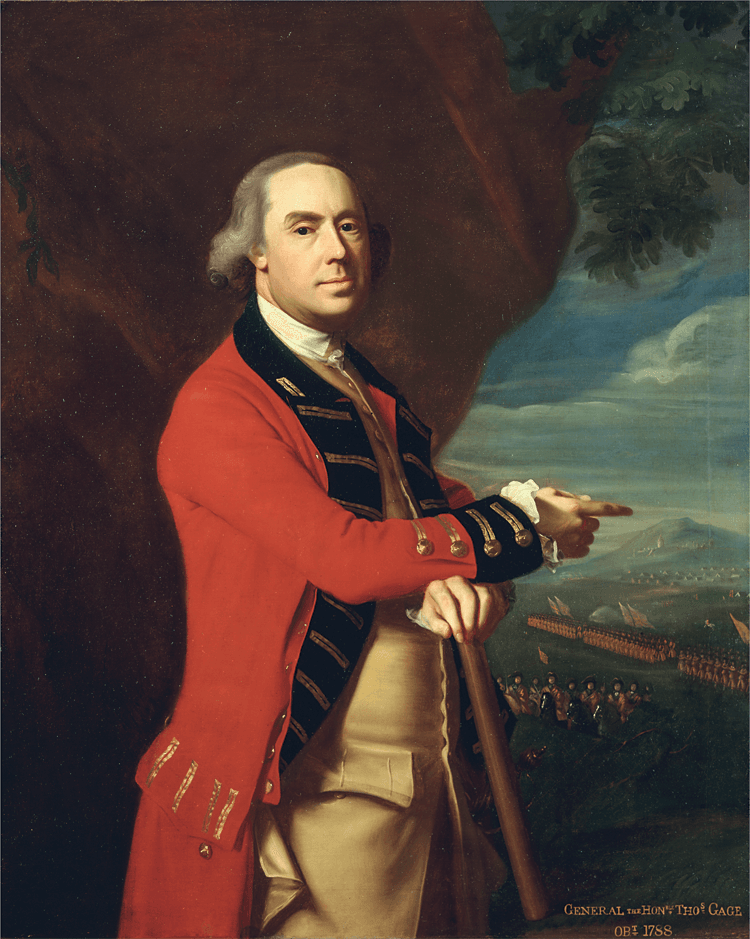

Gould was an astute businessman and was able to sustain his shop during a tumultuous era. He remained politically neutral during the Revolutionary conflict, serving clients on both sides. His most important Loyalist client was General Thomas Gage (Fig. 11), head of the British forces in New England, who ordered thirteen pieces of furniture from Gould in 1774 to furnish his summer headquarters in the Robert “King” Hooper mansion in Danvers, Massachusetts. Gould was also involved in the furniture export business, a trade that was generally thought to have started much later in Salem. Local vessels carried 616 pieces of furniture made in the Gould shop or purchased by Gould from subcontractors for resale to southern ports and the Caribbean as venture cargo. Desks made entirely of cedar were the most popular export item because the distinct smell of the wood repelled wood-eating insects, so prevalent in tropical regions.

There is much more to learn about Gould’s furniture production, with examples of many of the forms he produced yet to be located. Possessing extraordinary skills as a cabinetmaker and with a refined sense of design, he was able to craft furniture of exceptional beauty, such as the desk-and-bookcase made for the Cabot family (Fig. 12), a piece that ranks among the very best produced in New England during the colonial period.

In Plain Sight: Discovering the Furniture of Nathaniel Gould is at the Peabody Essex Museum, Salem, Mass., from November 15, 2014, to March 30, 2015. For information call 978.745.9500 or visit www.pem.org.

Dean Lahikainen is the Carolyn and Peter Lynch Curator of American Decorative Art at the Peabody Essex Museum, Salem, Mass.

This article was originally published in the Winter 2014 issue of Antiques & Fine Art magazine, a digitized version of which is available on afamag.com. AFA is affiliated wiht Incollect.

2. See Kimble Widmer II and Joyce King’s, “The Documentary and Artistic Legacy of Nathaniel Gould,” in American Furniture (2008): 1–25, and In Plain Sight: Discovering the Furniture of Nathaniel Gould (Salem, Mass.; Peabody Essex Museum, 2014).