International Styles: Reconfiguring the American Wing at The Baltimore Museum of Art

Reconfiguring the American Wing at The Baltimore Museum of Art

Celebrating its 100th anniversary, the Baltimore Museum of Art opens its newly reconfigured American Wing this November. The reinstallation concentrates on particular strengths of the BMA including colonial portraiture, Federal inlaid and painted furniture, American silver, and early twentieth-century modernist paintings. A suite of nine galleries, along with a group of eighteenth-century Maryland period rooms, will feature approximately 850 works in all mediums. Spanning over two centuries, the works range from teaspoons to salon paintings. Integrated painting, sculpture, furniture, silver, ceramics, and glass are interpreted thematically to tell the story of American art within an international context.

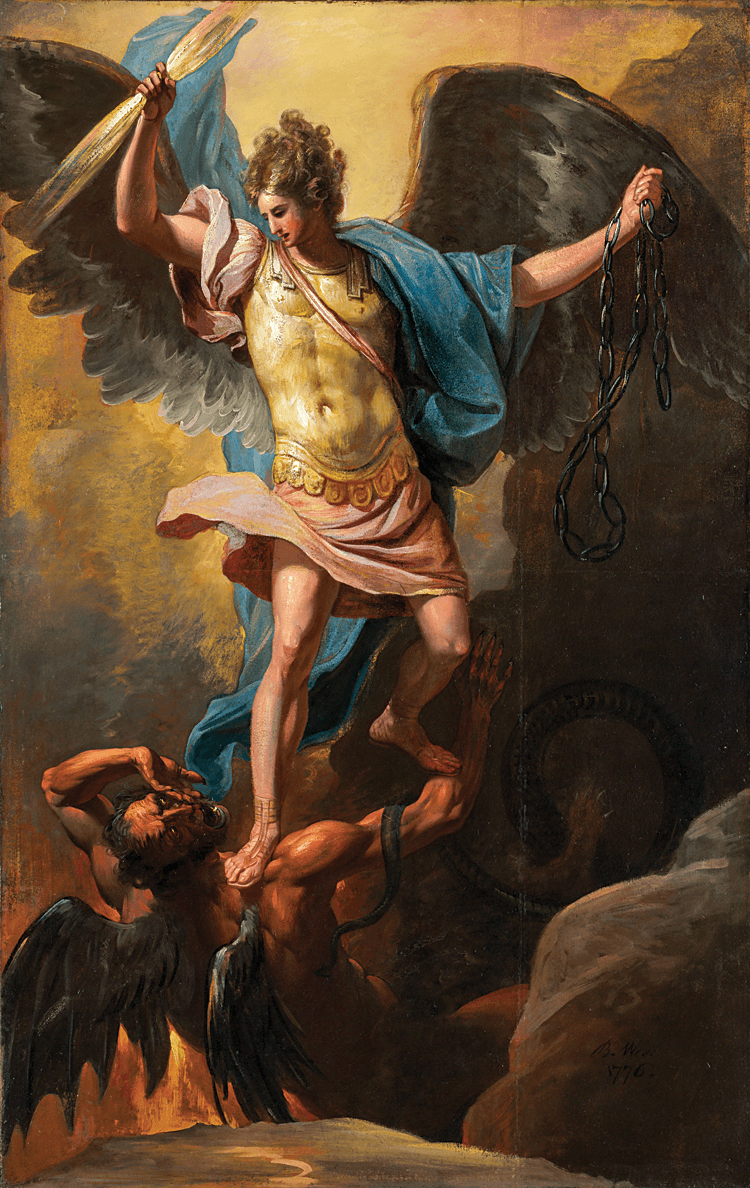

- Benjamin West (1738–1820), St. Michael and Satan, 1776.

Oil on paper mounted on canvas, 46¼ x 29½ inches.

The Baltimore Museum of Art: W. Clagett Emory Bequest Fund, in memory of his parents, William H. Emory and Martha B. Emory; Friends of the American Wing Fund; Harriet and Jeffrey Legum Fund; and purchase with exchange funds from bequest of M. Carey Thomas, in memory of Mary Elizabeth Garrett (BMA 1999.67).

Painted a decade after Benjamin West removed permanently from the American colonies to London, this highly finished oil study for an altarpiece features the Archangel Michael grasping a lightning bolt as he tramples evil. Based on a passage from the Bible’s Book of Revelations, the impetus for West’s apocalyptic image was twofold: First, West had absorbed Edmund Burke’s influential treatise, Philosophical Enquiry into the Origin of Our Ideas of the Sublime and Beautiful (1757), which considered how artists might evoke fear and a sense of the supernatural in their work. Second, in 1775, the Master of Trinity College, Cambridge University, who had commissioned the altarpiece from West, was advocating a policy of coercion against the American colonies. As an American expatriate painter, West walked a fine line with his British patrons. Here he lets the viewer decide who was angel and who was devil.

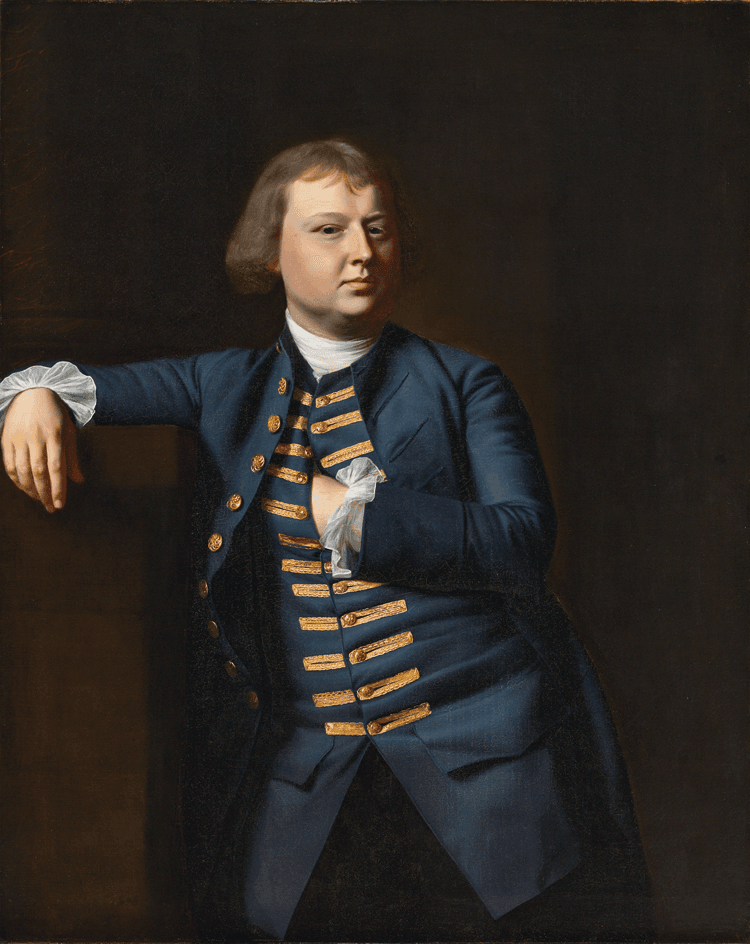

Portraits present sitters as they wish to be perceived. Dressed for success, the up-and-coming Lemuel Cox (1736–1806), a master mechanic, strikes the nonchalant pose of a gentleman, including one hand thrust into his waistcoat in a gesture recommended by etiquette books to express “Decency and genteel Behaviour.” John Singleton Copley based the pose in part on the Apollo Belvedere, a classical sculpture that, from the mid-eighteenth century, epitomized ideals of aesthetic perfection. The year Cox sat for this portrait he designed a yarn processing machine, reducing American dependence on English fabrics amid growing resentment of British taxation on imported goods. Although Cox took the side of the patriots in 1770, he seems to have altered his political views by 1775, when he was briefly imprisoned on suspicion of spying for the British. He left the country shortly thereafter. On his return, Cox’s engineering skills as a bridge designer eventually brought him fame. In 1785–1786, Cox supervised construction of the first bridge to span the River Charles at Boston, Massachusetts. He designed another bridge at Waterford, Ireland, in 1793. Colloquially called Timbertoes, it was as solid as its confidently posed designer, remaining in use into the early twentieth century.

In their first flush of wealth, fashionable Marylanders supported a thriving furniture trade. Between 1760 and 1810, about 190 individual cabinetmakers and partnerships were active in Baltimore. One such partnership began when Richard Lawson (1749–1803) arrived in Baltimore, having worked many years for Seddon and Sons, a large London furniture firm. Armed with firsthand knowledge of cutting-edge style and London construction methods, he quickly partnered with John Bankson (1754–1814). Their seven-year collaboration, which lasted until 1792, produced fine Federal furniture with distinctive inlays like the eagle on this desk. Once broadly dated as late as 1810, these pieces are now thought to represent the first manifestations of Baltimore’s significant contribution to inlaid neoclassical furniture.

A study in sumptuous simplicity, this magnificent neoclassical soup tureen is one of the finest known examples of early Maryland silver. Devoid of superfluous ornament, it relies on simplified lines and large reflective surfaces for its powerful visual impact. A cast finial on the lid reiterates the tureen in miniature. Sadly for the corpus of Baltimore Federal silver, the talented Charles Louis Boehme gave up silversmithing sometime around 1812 to pursue other interests.

Painted in Florence, Italy, Thomas Cole’s Wild Scene adapts the compositional strategies of the baroque landscape painter Claude Lorrain (ca. 1600–1682) to an American subject. The BMA’s painting is the precursor to an ambitious project involving five similarly sized canvases depicting the metaphoric rise and fall of a mythic city. Entitled The Course of Empire, the series was meant to illustrate what the artist called “the mutation of earthly things” at a time when many Americans feared that the pastoral prosperity of early nineteenth-century America would give way to economic and political greed, followed by inevitable decay. The first of Cole’s five canvases (all now in the New-York Historical Society) draws on the composition of A Wild Scene, where Native Americans— considered by eighteenth-century Europeans to be living in a natural state free from the corrupting influences of Western civilization—hunt a deer a in the dim light of a stormy dawn in an imagined valley. Cole hoped that the entire project would attract the support of Baltimore patron Robert Gilmor Jr., but Gilmor merely accepted the BMA picture in payment for funds already advanced to Cole for travel.

Painted to suggest the dramatic grain of rosewood, this center table—a newly fashionable form at the turn of the nineteenth century—is all about imitation. Perched on saber-shaped legs, it features hard-edged stencils imitating gilt brass. Fierce winged thunderbolts and stylized palmettes give way to softer stenciled fruit and foliage rendered in muted colors on the deep table skirt. A vivid oak and acorn pattern wreathes the top edge. This decoration frames the main event—a plaster top depicting the temples of Vespasian and Saturn in the Roman Forum. Poetic images of this ancient site had been in print since the mid-eighteenth century. While the pedestal base was made in Baltimore, the plaster top was imported, evidence that American decorative arts were international in scope. The image of romanticized ruins in a Baltimore parlor signaled America’s abiding interest in antiquity. Originally part of an elaborate suite belonging to James Wilson (1775–1851), a wealthy Baltimore merchant, the aggressively ornamented table restates the social and economic confidence of Baltimore’s rising mercantile class as the nation grew toward international power.

- Pair of spill vases depicting “Uncle Tom and Eva” and “The Flight of Eliza,” Limoges, France, 1852–1853.

Biscuit and glazed hard-paste porcelain and gilding. H. 11½, W. 8¾, D. 63⁄16 inches.

The Baltimore Museum of Art: Albert H. Cousins Memorial Fund; and purchased as the gift of Ann Bosworth (BMA 2002.205.1, 2).

Three famous characters from Uncle Tom’s Cabin by Harriet Beecher Stowe embellish these French vases, made to hold spills—slender twists of paper used to light fireplaces. The figures of Uncle Tom and Eva in a garden on one vase, and Eliza escaping slavery across a frozen river on the other, were inspired by printed illustrations for Stowe’s landmark piece of nineteenth-century fiction. An ardent abolitionist, Stowe wrote her text in response to the second Fugitive Slave Act (1850), which diminished the rights of both free and fugitive African Americans and punished anyone who aided runaways. Stowe was partially inspired by the autobiography of Josiah Henson, a slave who fled a tobacco plantation in North Bethesda, Maryland, making his way to Canada in 1830. First serialized in an abolitionist magazine, Stowe’s chapters were published as an illustrated novel in 1852. Translated into many languages, Uncle Tom’s Cabin soon became the second best-selling book in the world after the Bible. The popular novel and its illustrations stimulated numerous spin-offs, including these rare ornamental vases, manufactured in Limoges, a bustling French porcelain manufacturing city that exported quantities of wares to the United States.

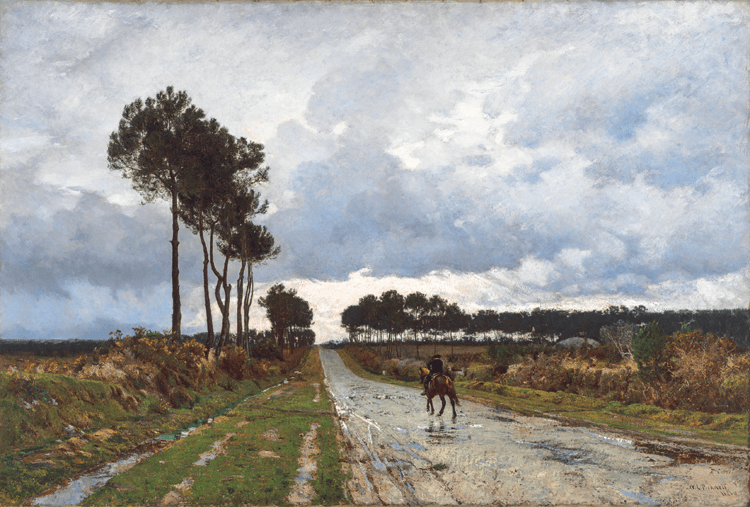

Orchestrated on a grand scale with a somber, silvery palette and an almost brutal painterly surface, William Lamb Picknell’s landscape represents French-influenced American modernist painting at a key point. The dark “Old-Masterish” canvases of the Munich School were giving way to light effects most famously initiated by French Impressionists during the 1870s and early 1880s. Paysage depicts a road leading towards Concarneau in Brittany. Picknell lived in neighboring Pont-Aven, where an American expatriate art colony flourished, led by Robert Wylie. Picknell adopted Wylie’s energetic use of the palette knife to apply swathes of heavy pigment in a manner reminiscent of Gustave Courbet. Despite their size, Picknell’s canvases were painted out of doors, with only minor finishing in a studio. Among thousands of pictures shown at the 1881 Paris Salon, a reviewer for the avant-garde journal Gil Blas singled out Picknell’s Paysage for praise, calling it “superb” and “one of the most remarkable pictures in the exhibition.” A year earlier, Picknell had received honorable mention as a landscape painter at the Paris Salon, the first American ever to be so recognized.

A lazily looping ribbon barely contains a riot of fruits and flowers in Tiffany’s extravagant stained glass composition. It centered a three-piece over-door transom window made for the dining room of Baltimore suffragist and philanthropist Mary Elizabeth Garrett and her partner, Martha Carey Thomas, an American educator, suffragist, linguist, and second President of Bryn Mawr College. Whimsical goldfish, swimming in two suspended circular fish bowls, are easily spotted. More challenging to find are six little blue birds hiding amidst the flower petals. In 1899, Art Nouveau entrepreneur Sigfried Bing exhibited Tiffany’s original cartoon for this window at the Grafton Galleries, London, showing it along with paintings by French Impressionists such as Claude Monet and Camille Pissarro. Indeed, Tiffany’s work was a novel form of painting with light. Skilful artisans, many of them women, created spectacular light effects by plating different pieces of colored glass in layers, following the cartoon. Tiffany himself liked the flower, fish, and fruit design so much that he later replicated it for his personal retrospective gallery of stained glass windows at Laurelton Hall, his Long Island country house.

Starting in the late 1880s, Theodore Robinson made regular visits to Giverny, where the French Impressionist master Claude Monet maintained his studio and famous garden. Inspired by Monet’s work, Robinson frequently chose to paint at sites nearby. Here, he captures a local resident, Père Trognon, watering his horse by a small bridge near the center of the village. Traces of a grid visible through thinly painted passages suggest that Robinson may have used a photograph to arrive at a preliminary composition. The finished canvas exhibits Robinson’s fully developed brushwork and fragile yet vibrant tonalities. The Watering Place was one of the first impressionist paintings to enter a Baltimore collection. Moses Cone provided funds for Etta Cone to purchase this picture at Robinson’s estate sale in 1898.

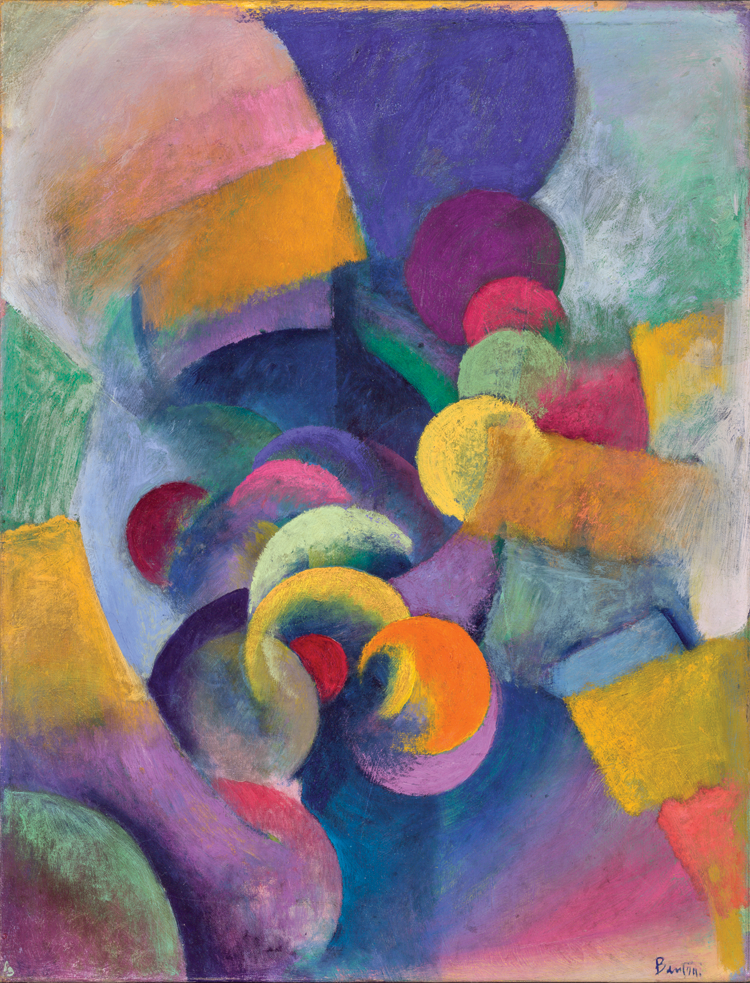

Donated by Baltimore-born cultural commentator H. L. Mencken, Bubbles records Thomas Hart Benton’s interest in “Synchromism,” an experimental form of painting that equated color with sound. Synchromism encouraged painters to compose color harmonies “scientifically,” just as musicians compose music by building sounds into harmonious chords. Benton encountered the movement in Paris and gave it a try. The original frame suggests that he knew about the radical green picture frames used by Impressionists Edgar Degas and Mary Cassatt. When later taste dictated that Bubbles be framed in a more conventional manner, the original molding was covered over with linen and used as a liner rather than being discarded. Conservators found that Benton had painted his frame a muted teal blue, a color that also appears in the picture itself. When displayed within this simple surround, Bubbles is transformed: the entire work looks bigger because the color field has been enlarged.

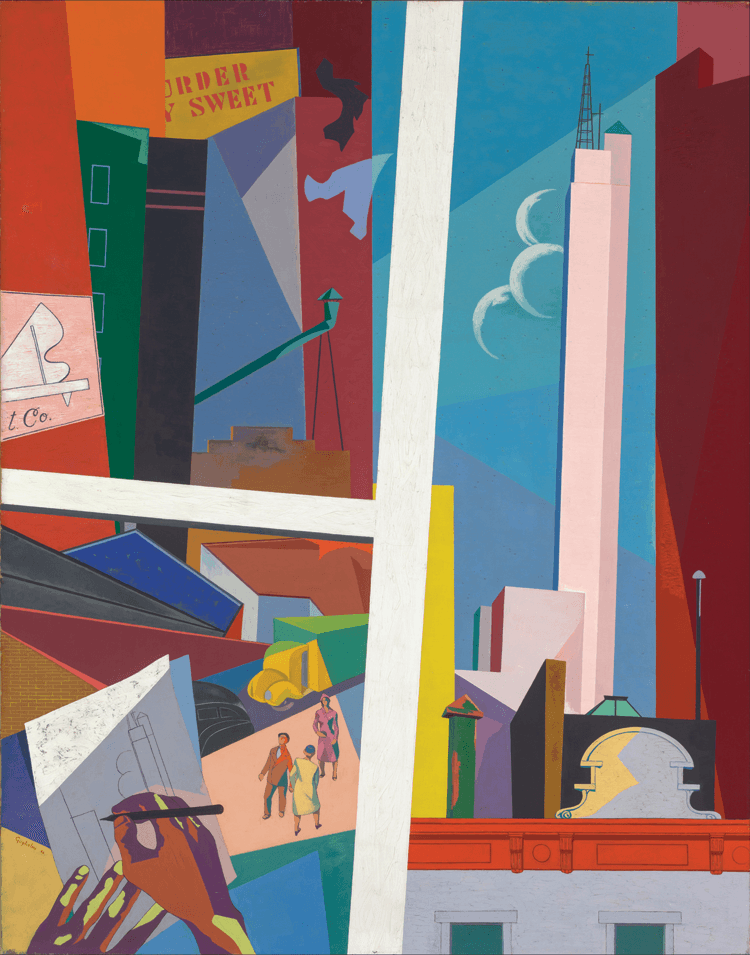

Growing up in an Italian immigrant family in Harlem, New York, Louis Guglielmi watched Manhattan develop and change. His earliest Social Realist urban scenes reveal the impact of hard times during the Great Depression, when he was living hand-to-mouth, working for the Works Progress Administration. This painting is a later autobiographical work that shows a more positive relationship to his adopted city. At bottom left, Guglielmi’s sure hand sketches a view that dominates the right side of the canvas. Here, bold skyscrapers rise to the clouds above the old nineteenth-century buildings, where Guglielmi grew up. One well-dressed pedestrian looks up in awe, while streamlined traffic evokes the rapid pace of city life. Yet the artist still sounds an anxious note. Incorporating fragments of commercial advertising—a technique borrowed from earlier French modernists—he includes not only a piano poster, suggesting music, but also a partially visible red and yellow broadside for a hard-boiled 1944 film noir, Murder, My Sweet, based on a novel by Raymond Chandler.

- Joseph Cornell (1903–1972), Untitled (Ligne Ostende-Douvres), ca. 1956.

Wood, nails, glass, cork, silver, metal, plastic, paint, paper, 8⅜ x 18⅛ x 39⁄16 inches.

The Baltimore Museum of Art: Purchased as the gift of Charles W. Newhall III and Nancy L. Dorman, and with exchange funds from bequest of Saidie A. May (BMA 2000.152).

Using found objects gathered in and around New York City and composing them carefully in a box of his own construction, Joseph Cornell followed the Surrealist principle of irrational juxtaposition. Cornell’s balls, bracelets, butterfly imagery, and broken goblets evoke a nostalgia that softens their unsettling combination. Here, the phrase Ligne Ostende-Douvres implies travel across the English Channel between Ostend, Belgium, and Dover, England. Cornell’s friend Robert Motherwell mused, “What kind of man is this, who . . . has reconstructed the nineteenth-century ‘grand tour’ of Europe for his mind’s eye more vividly than those who took it, who was not born then and has never been abroad . . . ?” Recalling his familiarity with multiple modernist movements, Motherwell marveled at Cornell’s ability to “incorporate this sense of the past in something that could only have been conceived of at present.”

In the late 1700s, a rising mercantile class helped to position Baltimore as a crossroads of international trade. These sophisticated consumers strove to demonstrate their New World position and welcomed newly arrived silversmiths, cabinetmakers, and painters who drew upon then-current European fashions. The museum’s collections—and the colonnaded Beaux-Arts structure designed by John Russell Pope in 1929 to house them—reveal this rich artistic legacy of the neoclassical tradition. Maryland’s lasting involvement with neoclassical aesthetics in art, architecture, and decoration continued well into the twentieth century.

As the United States became a growing economic power in the nineteenth century, artists took a more conscious international stance, studying and traveling abroad, and developing international connections and ambitions. Landscape painting became the dominant mode of expression in mid-nineteenth-century American art, translating earlier Italian compositional strategies into views of America’s vast, unspoiled wilderness. During these years, Americans experienced nature not only through paintings, but also via the founding of the national park system, the growth of natural history museums, and expanding tourism.

With the nation’s post-Civil War prosperity came the recognition by both artists and their patrons of the need for rigorous training in European capitals. American expatriates entered the mainstream of realist and impressionist developments abroad. Others translated their European experience into providing artistic training back in the United States. Decorative arts, often designed by European immigrants and displayed in world fairs, reflected the meeting of cultures, the allure of objects from distant parts, and the use of historic designs to temper the shock of social, economic, and technical change. New money, new technological developments, and new audiences conspired to make the late nineteenth century an arena in which the decorative arts achieved critical and commercial success on a par with architecture, painting, and sculpture of the period. During the twentieth century, Baltimore’s taste for modernity continued with avid interest in European and American avant-garde painting, demonstrated in the BMA’s public exhibition record as well as the activities of prominent local collectors.

Together, the works housed in the BMA form part of a century-old theater of memory that is the ultimate legacy of any public art collection. The doors of the Dorothy McIlvain Scott American Wing open to the public on November 23, 2014. Admission is free. For information, visit www.artbma.org or call 443.573.1700.

Dr. David Park Curry is senior curator of decorative arts, American painting, and sculpture at the Baltimore Museum of Art.

This article was originally published in the Winter 2014 issue of Antiques & Fine Art magazine, a digitized version of which is available on afamag.com. InCollect.com is a division of Antiques & Fine Art, AFAnews, and AFA Publishing.