All That Glitters: Jewelry from New York's Gilded Age

This article was originally published in the Autumn 2015 issue of Antiques & Fine Art magazine.

In the decades following the Civil War, vast sums of money were made in mining, railroads, manufacturing, finance, and commerce. New York City was the epicenter for those involved in such activities. By 1892, one-third of the country’s millionaires resided in Manhattan. For the newly rich, as well as the members of old New York society, the grand homes they began to build in the farther reaches of Fifth Avenue required costly, magnificent interiors and, by extension, equally refined dress and jewelry for stylish entertaining. While many New Yorkers purchased jewelry abroad during their travels, more began to avail themselves of jewelry made in New York, where Gilded Age fortunes led jewelers to create their best works, using the most extravagant materials. In so doing, they ushered in the first truly great era of American jewelry.

Purchases of jewelry were secondary to wearing them, as visitors to New York’s Metropolitan Opera often discovered, for sparkling ornaments made actors out of their owners and created brilliant performances that sometimes outshone those taking place on stage. Many attended the opera simply to glimpse society women wearing their newest jewelry purchases in public; a voyeurism easily achieved with a pair of opera glasses (Fig. 1).

Some enterprising jewelers left their historic locations in lower Manhattan and moved uptown in order to be closer to their patrons. Chief among them was Tiffany & Co. In 1837, Charles Lewis Tiffany and John Burnett Young established a small fancy goods store at 259 Broadway and the business soon expanded to include imported jewelry. In 1848, during the overthrow of French King Louis Philippe I, jewelry purchased from fleeing aristocrats led to Tiffany’s fast-rising reputation as a purveyor of important gemstones. After Tiffany assumed control of the firm in 1853, he renamed it Tiffany & Co. He moved the shop northward several times, following the residential patterns of his clientele. To garner attention, the firm participated in expositions such as the Philadelphia Centennial in 1876, where they received awards for their silver and jewelry. Satellite galleries in Paris (1850) and London (1872) served Americans traveling abroad as well as Europeans who began to appreciate the Tiffany name. Profiting a second time from France’s changing aristocratic fortunes, Tiffany actively participated in the sale of the French Crown jewels in 1887. Bidding for themselves and on behalf of private clients, the firm successfully won one-third of the lots, more than any other competitor.

- Fig. 3: Necklace, Tiffany & Co. (founded 1837), ca. 1890–1895. Platinum, gold, diamonds.

Collection of Dr. Julia A. McMillan and Mr. J. E. Dietz.

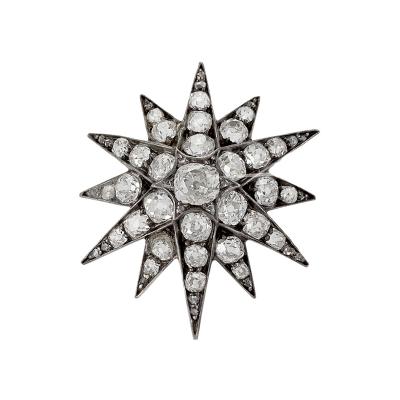

Diamonds formed a major portion of Tiffany & Co.’s sales, as evidenced by one of the only known surviving tiaras by the firm, made for the 1894 wedding of Julia Kemp. Her father, George Kemp, exemplifies the American success stories of the era. He emigrated from Ireland with his widowed mother and five siblings in 1830; by 1858 he was leading a major pharmaceutical firm. Kemp’s home on Fifth Avenue was decorated in the aesthetic style by Associated Artists, the interior design firm founded by C. L. Tiffany’s son, Louis Comfort Tiffany, Lockwood De Forest, Candace Wheeler, and Samuel Colman. By 1894, when his daughter married into an old New England family, Kemp was able to present her with a diamond tiara (Fig. 2). Similarly, diamonds play a central role in an impressive platinum and gold graduated link necklace, originally given a dual purpose with a tiara fitting, now lost. Owned by Julia Dent Grant (1826–1902), widow of Ulysses S. Grant, the 18th president of the United States, the necklace was elegant, if sober, as would have been fitting for a woman in her seventies (Fig. 3).

One of the figures who led the changes in jewelry design and materials at Tiffany & Co. was George Paulding Farnham, who created a series of orchid brooches that caused a sensation at the Exposition Universelle in Paris of 1889. At the time, live orchids were rare and costly specimens that few could afford; as jewelry, they were even more rarified. Farnham captured the delicacy and beauty of each species, breathing life into them with subtly colored enamels and a sprinkling of precious stones (Fig. 4). Farnham was equally adept at designing within the all-white aesthetic of diamonds and platinum, so popular at the turn of the century. It was under his tenure that a diamond spray (Fig. 5), made in 1901 by Tiffany & Co. for the Pan-American Exposition in Buffalo, New York, was purchased by American lawyer and statesman Elihu Root (1845–1937) for his wife Clara Frances Wales Root (d. 1928), probably for their 25th wedding anniversary; Root was Secretary of War under Theodore Roosevelt at the time of this purchase.

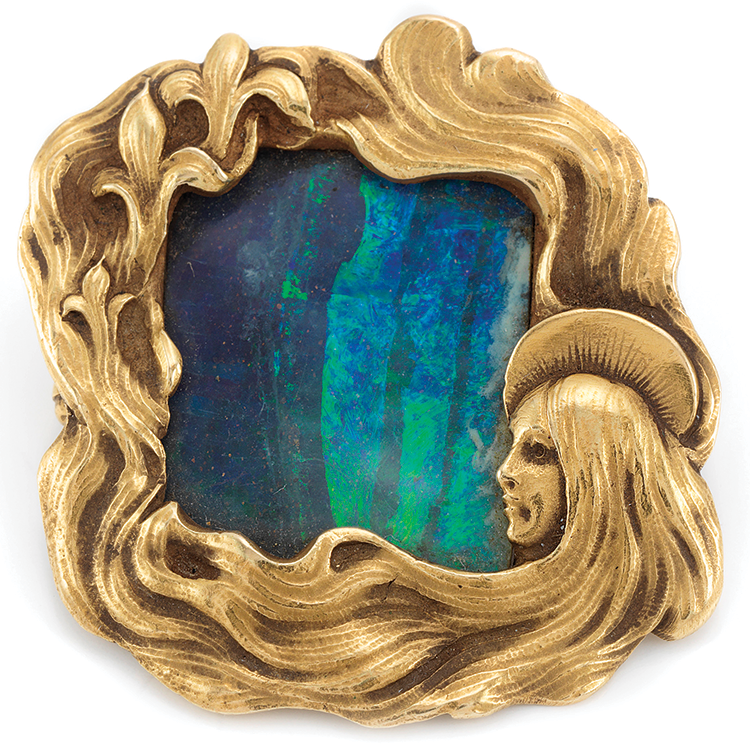

With his superior knowledge of gemstones, wide-ranging intellect, and restless energy, George Kunz enabled Tiffany & Co. to introduce a range of colored gemstones such as sapphires, amethysts, and turquoise to the public (Fig. 6). His gem discoveries enhanced Farnham’s designs, as well as those of Louis Comfort Tiffany, who was a great student of nature and a colorist at heart. With the death of Charles Lewis Tiffany in 1902, the younger Tiffany may have at last felt free to experiment with an art form that had been a central element of his father’s firm. Preferring cabochons to cut stones, L. C. Tiffany sought to create a naturalistic appearance in jewelry whenever possible. He employed enamel to convey color and depth, and gold leaves and tendrils to secure stones, instead of prongs, giving the appearance of brilliant color on a forest floor (Fig. 7).1

A firm also known for its interest in colored gems was Marcus & Co., named for Herman Marcus. Born in Germany, where he learned his trade, Marcus worked for the leading New York jewelry retailer Ball, Black, & Co. before setting out on his own, first with Theodore B. Starr to form Starr & Marcus. At the Philadelphia Centennial, where they exhibited, one reporter noted; “No one who looked upon the glittering array of faceted brilliants exhibited by Starr & Marcus of New York. . . could regret the cutting and polishing process that resulted in the production of these superb jewels.” 2 Marcus later worked in Tiffany’s diamond department and represented the firm at the Paris exhibition. By 1884, he joined Jaques & Marcus (the latter Marcus being his son, William Elder Marcus), which in 1892 became Marcus & Company.

Throughout these changes, Herman Marcus was known for the quality and the range of colored stones that he used, as well as for his curvaceous designs softly ornamented with a graduated, beaded pattern. As Marcus & Co., the firm entered a period of great productivity in which unusual gems such as peridot, boulder opal, jade, and dogtooth pearls were set in elaborate, often interlaced settings (Fig. 8). The firm’s brilliant handling of enamel was second to none in this period. Among the very best of these were translucent plique-à-jour enamels that illuminated naturalistic arrangements of flowers and leaves (Fig. 9).

Theodore B. Starr (1837–1907), an early partner of Marcus, founded his eponymous store in 1877 to rival any in New York for the range and quality of its luxury goods (Fig. 10). Starr was the exclusive representative of Tiffany’s chief silver rivals, Gorham & Co., in the city. The store, which boasted an elevator, was called a “veritable cave of Aladdin.” It featured silver at street level, jewelry on the second floor, and sculpture and clocks on the third.3 In 1911, a larger and more impressive structure was erected uptown at 47th Street and Fifth Avenue, with private jewelry viewing rooms. In 1918 the firm was absorbed by Taunton, Massachusetts, silver manufacturer Reed & Barton.4

One of the most famous early American jewelers was Ball, Black, & Co., whose history extended back to 1801, when it operated as Marquand and Paulding in Savannah, Georgia. By 1810 Isaac Marquand had settled his shop in New York, where it remained through many business partnerships, until 1874, when it became Black, Starr & Frost, with new partners Cortlandt Starr and Aaron Frost. Black, Starr & Frost were among the few American companies to exhibit at the 1851 Crystal Palace in London. From an early location on lower Broadway, the firm moved up Fifth Avenue to 28th Street, in 1876; 39th Street in 1898; and 48th Street in 1912. At the turn of the century their jewelry was best known for its platinum and diamonds, with delicately colored accents using unusual turquoise cabochons and pink conch pearls (Fig. 11 ).

Another Broadway-based jeweler was Dreicer and Co. (1868–1926), whose first street-level shop was opened at 6 John Street near this thoroughfare by Jacob Dreicer and his wife Gita. The couple emigrated from Russia in 1866 and both were knowledgeable about gems before their arrival in Manhattan. Esteemed for the high quality of their gemstones, and for selling diamonds and pearls rendered in articulated platinum mounts, Dreicer’s skill was in his rapid interpretation for his American patrons of the latest styles in Paris, particularly at Cartier.5 Pearls were a special passion for Jacob Dreicer, who created large, matched ropes by painstakingly assembling them over time. Dreicer’s first shop was located beside Delmonico’s, where the jeweler dined and cultivated a wealthy clientele.6 In 1885 the firm moved to Fifth Avenue, at 30th Street, and later farther north, to 46th Street. In addition to opening a store in Chicago, the firm also operated seasonal shops in such fashionable watering holes as Saratoga Springs and Palm Beach.

- Fig. 10: Theodore B. Starr, Inc. (New York City, 1862-1918), retailer; glass probably by Thomas Webb & Sons, (Amblecote, England, 1837 to 1990), Swan-billed flask, 1885-1900. Cased and engraved glass, silver. L. 8¼ in. Courtesy of the Museum of the City of New York, Gift of Miss Maude Lacey (38.13.1a-b).

Jewelry designer Frank Walter Lawrence (1864–1929) enjoyed a successful career conjuring imaginative compositions, often with Egyptian and mythological motifs, using colored stones, ancient glass, and horn, as well as gold (Fig. 12). He apprenticed in New Jersey with Durand and Company (1869–1936), and with Jaques and Marcus (ca. 1882–1892) in New York before opening his first Manhattan location at 857 Broadway in 1889. Four years later, at 41 Union Square, he served a clientele less interested in diamonds and pearls than jewelry inspired by history, texture, and color. Craftsmanship and imagination, as opposed to the monetary value of jewelry, was a theme he promoted in his writing.7

Gustav Manz (1865–1946) executed a number of Lawrence’s designs (see figure 12). A talented, if unappreciated jeweler, Manz is known today because of his surviving drawings and ephemera, now stored at Winterthur Museum.8 Born in Stuttgart, Germany, near Pforzheim, a major gem-cutting and jewelry center, Manz learned his craft there and then traveled to Paris, England, and South Africa before arriving in Manhattan in 1893, where he became a manufacturing jeweler for many American firms. Manz fashioned jewelry in a wide range of styles for Tiffany & Co., Marcus and Co., Black, Starr, & Frost, and Gorham, among many others. The Manz papers have allowed us to better appreciate the contributions of Manz, on whose work the reputations of many well-known firms are based.

As America entered World War I, many jewelry houses faltered. Today, except for Tiffany & Co. and a recently revived Black, Starr & Frost, none of the firms mentioned here are extant. However, their fine ornaments remain to remind us of the skill, passion, and talent of the Gilded Age jewelers.

Gilded New York: Design, Fashion & Society, is on view at the Museum of the City of New York through January 2016. A catalogue edited by Donald Albrecht and Jeannine Falino, published by The Monacelli Press, can be ordered through the Museum’s shop at 917.492.3330 or at www.mcny.org.

Jeannine Falino, an independent curator, is co-curator of Gilded New York: Design, Fashion & Society.

This article was originally published in the Autumn 2015 issue of Antiques & Fine Art magazine, a digitized version of which is available on afamag.com. Antiques & Fine Art, AFAmag, AFAnews, and AFA Publishing are affiliated with InCollect.com.

2. Edward Strahan, Walter Smith, and Joseph M. Wilson, Masterpieces of The Centennial International Exhibition Illustrated (Philadelphia: Gebbie & Barrie, 1876), 460.

3. “A cave of Aladdin,” Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper, Issue 1213, December 28, 1878, p. 290; “Art in a jewelry store,” New York Times, April 16, 1881, p. 8.

4. “Fine Example of Business Architecture, The New Building of Theodore B. Starr, Inc., at Fifth Avenue and Forth-seventh Street, an illustration of what may be achieved along artistic lines,” Town and Country 66:31 (October 14, 1911), p. 60–61.

5. Hans Nadelhoffer, Cartier, (San Francisco, CA: Chronicle Books, 2007), 29.

6. E.D. Dakin, “Pearls Before House Wreckers, The Closing of Dreicer & Co. . . . ,” New York Herald Tribune (January 30, 1927): 9, 29.

7. Frank Walter Lawrence, “Craftsmanship Versus Intrinsic Value,” The Craftsman Vol. 4:3 (June 1903): 181–185. Janet Zapata, “The jewelry and silver of F. Walter Lawrence,” Antiques, Vol. 165: 4 (April 2004):124–133.

8. Courtney Bowers [Marhev], “Where Credit Is Due, The Life and Jewelry of Gustav Manz,” Antiques 177:5 (September/October 2010):168–175.