John Gadsby Chapman and James Kirke Paulding: Painting and Interpreting George Washington’s Virginia in the 1830s

On a warm day in May 1835, John Gadsby Chapman (1808–1889) left the bright Manhattan street for the softly lit galleries of the Eleventh Annual Exhibition of the National Academy of Design. The show’s opening was the twenty-seven-year-old artist’s debut to the New York art world and an opportunity to define his nascent career. Chapman had carefully chosen twelve paintings to showcase his ambitions to the highest level of nineteenth-century fine art: narrative history painting. Two of the pictures were portraits of American heroes: a bust-length President James Madison made during his retirement at Montpelier, and a life-sized portrait of Congressman Davy Crockett as a Tennessee hunter. Even more impressive were seven exquisitely detailed Virginia landscapes originally commissioned by the writer James Kirke Paulding (1778–1860) depicting places intimately related to George Washington’s life: the sites of his birth and boyhood homes (both of which had long since been destroyed); the Fredericksburg house of his mother; a view of his Virginia plantation, Mount Vernon; his tomb; Yorktown seen from a distance; and a recreated view of the bedchamber in which he died. Less than a decade after John Trumbull hung his paintings of the American Revolution in the United States’ Capitol, Chapman too hoped to shape the way his fellow countrymen imagined their history.

|

| Fig.1: John Gadsby Chapman (1808–1889), Baptism of Pocahontas, 1839. Oil on canvas, 12 x 18 feet. Courtesy, Architect of the Capitol. While Pocahontas’ rescue of John Smith would have been a more dramatic subject, Chapman chose her baptism to conform with the narrative of Native-American assimilation elsewhere in the Capitol’s decorative program. |

Expertly executed, well-researched, and detail-rich, the Chapman-Paulding series—the seven pictures exhibited at the National Academy and an additional two paintings presented to Paulding as gifts—testified to the artist’s yearning to paint the narrative of American history. At least initially, they did indeed launch Chapman into the field of history painting: two years after the National Academy exhibition, the federal government commissioned the artist to paint the monumental Baptism of Pocahontas. But when the work was installed in the Capitol Rotunda in 1840, it was met with mixed reviews. Ultimately, Chapman never supported himself as a history painter. Facing financial set-back after personal tragedy, the beleaguered artist spent his last decades painting and etching views of the Roman Campagna and genre scenes of Italian peasants. The Baptism of Pocahontas was his only major history painting.

And yet this is not the sad story of a failed artist. The Chapman-Paulding series did make a significant contribution to how Americans saw their past, if not how Chapman had intended. In a variety of ways, the series fed growing enthusiasm for America’s historic places in the decades that saw the passing of the Revolutionary generation. Through prints and illustrations derived from the works and tales that emerged from Chapman’s research for them, he made tremendous contributions to the development of a popular understanding of the history of the United States. The addition of the series to George Washington’s Mount Vernon’s nineteenth-century collections, purchased in 2017 with the generous support of Lucy S. Rhame and an anonymous donor, prompt a reappraisal of their place in the history of American art.

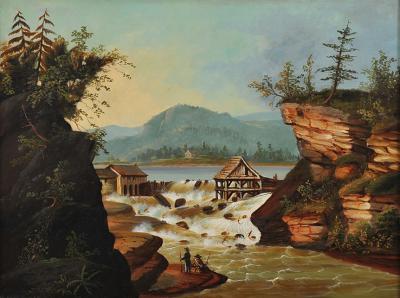

|

| Fig. 2: John Gadsby Chapman (1808–1889), View from the Site of the Old Mansion of the Washington Family [Ferry Farm], 1834. Oil on canvas, 21½ x 29 inches. Mount Vernon Ladies’ Association; Purchased with funds provided by Lucy S. Rhame and an anonymous donor (2017). The Rappahannock River divides the bustling City of Fredericksburg from the site of Washington’s boyhood home in the foreground. While Chapman knew the approximate appearance of the house, he chose to paint the scene and almost all others in the series in the present to emphasize the sense of romantic decay. |

.jpg) | |

| Fig. 3: John Gadsby Chapman (1808–1889), Moore’s House—Yorktown, Va., from The Family Magazine 1, no. 4 (April 1836): 121. Wood engraving, Archives & Special Collections. University of Louisville. The source painting for this engraving is one of two of Yorktown that Paulding commissioned from Chapman specifically for printing. Its mate was the frontispiece for the second volume of Paulding’s Washington biography. |

In 1835, Chapman had every reason to believe that he would be the next great painter of the United States’ short but storied past. He was one of the first American artists trained in Rome, having spent three years drawing classical sculpture, copying Old Masters, and painting the Italian countryside. The revered statesman of American painting, Thomas Sully, had encouraged the artist at a very young age. Most importantly, Chapman had a pedigree that aligned him closely with those in power: born in Washington, D.C., his grandfather had owned several of the largest hotels in the capital area, including Alexandria’s Gadsby’s Tavern, often frequented by George Washington himself. He counted on his long-exposure to the region’s elite to guide his brush and palette to distinguished federal commissions.1

It was James Kirke Paulding who emerged as Chapman’s most important patron. Paulding was associated with the circle of writers who contributed to the Knickerbocker magazine often known as the “Knickerbocker writers.” The group included such authors as William Cullen Bryant, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, and Washington Irving. While little remembered today, Paulding was well known in the period for his romantic blend of American history and fiction similar to the work of James Fenimore Cooper. Paulding’s own aim in his writing was to forge a new American literature. He commissioned the young Chapman to paint nine Virginia landscapes just two years after the artist’s return from Italy. Supported almost entirely by Paulding for more than a year, Chapman exercised the research skills of a history painter in service of the author’s latest venture: a biography of George Washington for young readers that would reveal the private man behind the public figure. Distancing himself from Mason Locke Weems’ infamous cherry tree tale, Paulding sought “authentic” stories about Washington’s character. With his close connections to the Washington family and strong Virginia roots, Chapman proved the ideal candidate for the project.

|

| Fig. 4: John Gadsby Chapman (1808–1889), Tomb of Washington, 1834. Oil on canvas, 21½ x 29 inches. Mount Vernon Ladies’ Association; Purchased with funds provided by Lucy S. Rhame and an anonymous donor (2017). By the time Chapman painted the tomb in which George Washington was initially buried at Mount Vernon, the family had moved Washington’s body to a new tomb and the earlier sepulcher was left in a state of romantic decay. |

|

| Fig. 5: John Gadsby Chapman (1808-1889), Distant View of Mount Vernon, 1834. Oil on canvas, 21½ x 29 inches. Mount Vernon Ladies’ Association; Purchased with funds provided by Lucy S. Rhame and an anonymous donor (2017). The fishermen in the foreground are the focal points of this picture rather than the mansion, allowing Chapman to demonstrate his talents for painting the effects of light on sky and water. |

The Chapman-Paulding paintings did not form a single cohesive narrative, but together served two distinctive purposes: Chapman received the opportunity to create a higher form of art, while his research fed Paulding’s new stories about Washington’s life. Chapman supported Paulding’s commitment to romanticized depictions of real places intended to draw the country’s “attention and its efforts to our own history, tradition, scenery, and manners, instead of foraging in the barren and exhausted fields of the old world.”2 Both men celebrated the unique Virginia landscape in much the same way that Thomas Cole and others were beginning to interpret the Hudson River Valley.

.jpg) | |

| Fig. 6: John Gadsby Chapman (1808–1889), Residence of Washington, Mount Vernon, from The Family Magazine (New York: Redfield & Lindsay, 1837), 281. Wood engraving. Boston Athenaeum. Chapman used the subjects of the paintings commissioned by Paulding as source material for simpler illustrations in popular magazines. |

Along with each painting, Chapman generated extensive notes describing the site itself, the research process he undertook, and any anecdotes that Paulding might find useful. Unfortunately, this documentation apparently only survives in one instance: a draft retained in Chapman’s papers of an 1833 letter he sent to Paulding detailing his trip to George Washington’s boyhood home. Among the inhabitants of nearby Fredericksburg, Chapman found a man who had been raised in the house and remembered its appearance. The painter detailed his conversation with the man, who appeared ashamed of the “miserably constructed & shabby house” in which he and the great Washington had lived.3 In Paulding’s two-volume biography, The Life of Washington, published two years later in 1835, the author transformed Chapman’s account into a lesson for his readers, believing that knowledge of Washington’s humble childhood would supplant the assumption that “rank, and birth, and wealth, and power are indispensable requisites to great virtues and glorious actions.”4

The paintings themselves also served in the illustration of Paulding’s publications on Washington’s life. When doing so, he often added details or cropped the content to enliven the images and to relate them more directly to the text. In his engraving of his painting of Washington’s birthplace for the title page, Chapman emphasized the rising sun and inserted a plaque installed at the site by George Washington Parke Custis in 1816. Chapman’s paintings (and surely his descriptions) of Yorktown also provided the raw material for Paulding’s 1835 article in The Family Magazine. Paulding praised the treatment of the building in which the ending of the Revolution was negotiated as evidence of Americans’ honest relationship with the landscape. Even though the house had hosted such a momentous event, it had been returned to its former use as a farmhouse in an actively cultivated field, just as Americans had experienced the sweet taste of victory and returned to their agrarian lifestyles. Chapman added a resting cow to the engraving that accompanied Paulding’s evocative description, emphasizing the bucolic atmosphere.

|

| Fig. 7: John Gadsby Chapman (1808–1889), Residence of Washington’s Mother at Fredericksburg, Virginia, 1834. Oil on canvas, 21½ x 29 inches. Mount Vernon Ladies’ Association; Purchased with funds provided by Lucy S. Rhame and an anonymous donor (2017). Mary Ball Washington, mother of George, became an icon of republican motherhood in the early nineteenth century and her house became a site of pilgrimage. |

Paulding’s commission launched Chapman’s career as an illustrator. The Washington biography proved popular, and in 1838, Paulding employed Chapman to illustrate his lavish A Gift from Fairy Land, published in New York in 1838 by D. Appleton & Co. The author also pushed the young artist to achieve his greatest ambition: along with Chapman’s boyhood friend and then Virginia Congressman, Henry A. Wise, Paulding helped Chapman to secure the commission for the massive Baptism of Pocahontas. But, as noted previously, the project was not to be a success. The loss of three children in two years and mounting debts led Chapman to rush to complete the project in order to collect the $10,000 commission in 1840. The painting ultimately found only lukewarm reception, as Chapman’s choice of subject lacked the drama and imagination of the others in the Rotunda.5

Despite ultimately falling short of his expectations, Chapman—along with Paulding—did significantly shape the ways in which mid-nineteenth-century Americans saw their past. The Chapman-Paulding series marked a turning point for how Americans remembered historic places. They claimed that the American landscape was worthy of art and literature because of both its beauty and its history. Chapman’s images and Paulding’s words also fueled the nation’s realization of the vanishing of its material past. In a review of Chapman’s work at the National Academy, one critic wrote of the painting of Washington’s birthplace: “The house is no more!—why could it not have been preserved as a shrine of the patriotick [sic] pilgrim!”6 In time, the romantic reverence expressed in Chapman’s works turned to activism as Americans sought not only to remember their past, but also to preserve it. First came Mount Vernon: with public concerns for the plantation’s future erupting over the state of the hero’s tomb in the 1830s, Chapman’s various depictions of the sepulcher, the house, and its famous landscape illustrated the growing interest in the place and the belief in its centrality to the formation of Washington’s character. Engraved in numerous popular histories and magazines, Chapman supplied a demand for images that climaxed in the formation of the Mount Vernon Ladies’ Association of the Union and its successful nationwide fundraising campaign in the 1850s to purchase the property and open it to the public. Chapman’s depiction of the Fredericksburg home of Washington’s mother prefigured efforts to save the house by sixty years. Paving the way for the Colonial Revival to come, the Chapman-Paulding series fueled the nation’s love for its own story.

Lydia Mattice Brandt is associate professor of art and architectural history at the University of South Carolina in Columbia, S.C. Adam T. Erby is associate curator at George Washington’s Mount Vernon.

This article was originally published in the Winter 2017 issue of Antiques & Fine Art magazine, a fully digitized version of which is available at www.afamag.com. AFA is affiliated with Incollect..

2. James Kirke Paulding to Thomas W. White, March 7, 1834, in James K. Paulding, The Dutchman’s Fireside: A Tale, ed. William I. Paulding (New York: Charles Scribner and Company, 1868), ix.

3. John Gadsby Chapman to James K. Paulding, November 11, 1833, Chapman Family Correspondence and Other Documents, 1791–1898 (MSS 0048), Special Collections and Archives, University of California, San Diego. The authors are grateful to Cassandra Good for alerting them to this collection.

4. James Kirke Paulding, The Life of Washington, vol. 1 (New York: Harper & Brothers, 1835), 19–21. The author appears to have conflated Washington’s birthplace and boyhood home, as his description of the house corresponds most directly with the description Chapman recorded of Ferry Farm, rather than the 18th-century appearance of the birthplace.

5. Robert S. Tilton, Pocahontas: The Evolution of an American Narrative (Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press, 1994), 116–124; John Gadsby Chapman, “Memoranda of Pictures & c.,” 37–79, McGuigan Collection, Milford, Pa. The authors are grateful to Mary K. and John F. McGuigan Jr. for access to the artist’s account books and other papers in their collection.

6. “Original Notices of the Fine Arts, The Artists’ Studio,” The New-York Mirror 12, no. 38 (March 21, 1835): 301.