John Singer Sargent and His American Contemporaries in Venice

Born to American parents in Florence, Italy, in 1856, John Singer Sargent spent his youth traveling through Europe with his family. From 1874 to 1885 he lived in Paris, receiving formal training in fine art and forming friendships with artists from around the world, including American painters. On visits extending from 1880 into 1881 and again in 1882, Sargent returned to Italy for several months at a time, beginning his mature artistic exploration of the city of Venice. An American art colony had already begun to form there and these artists were joined by painters and printmakers from a number of European nations, as well as artists from various provinces of the newly united Italian Kingdom; and more significantly, a thriving and innovative company of Venetian painters. Moreover, after shaking off Austrian occupation in 1866 and joining the Kingdom of Italy, the somewhat impoverished city-state of Venice began to be home to a group of wealthy Anglo-American expatriates who not only bought up some of the grand palaces of the city, but also immersed themselves in Venetian culture.1 By the last decades of the nineteenth century, Venice had succeeded Rome as a Mecca for international activity.

American painters had been active in Venice since Colonial days; Benjamin West sojourned there in 1772. But the year 1877 marks the appearance of “modern” American art in Venice when realist painter Frank Duveneck (1848–1919) and future impressionists William Merritt Chase (1849–1916) and John Twachtman (1853–1902) arrived in Venice from Munich where they had trained and later worked. Duveneck’s early Venetian paintings have not come to light, but a good number by Chase and Twachtman are known, including the latter’s Venice, Campo Santa Marta (Fig. 1) where the rough, tonal aesthetic bespeaks the modern Munich method, while the choice of deliberately unromantic and nontraditional views of the city foreshadow the approach that later artists such as tonalist painter James Whistler (1834–1903) and Sargent would adopt in their delineations of the city.2

In October 1879, Duveneck, with his Munich students, referred to at the time as his “boys,” had moved permanently from Munich to Italy, holding winter classes in Florence and spending his summers with his students in Venice, where they became close with Whistler. In Venice, Duveneck painted the local working class, his large Water Carriers, Venice (Fig. 4) is a particularly good example,3 as well as canal scenes strikingly similar in technique and mood to those of Guglielmo Ciardi, the leading Venetian painter of such subject matter.

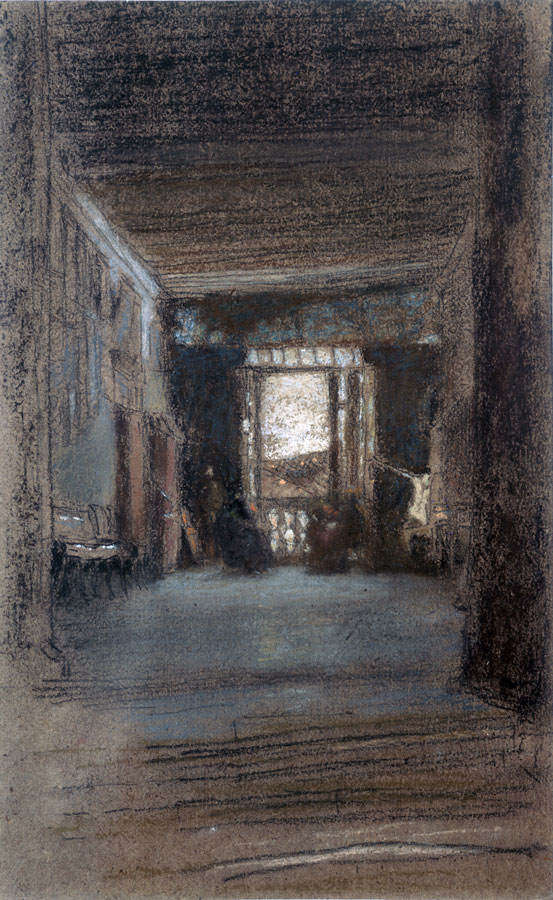

Whistler had arrived in Venice from London for a fourteen month stay in September 1879 on a commission to create a series of etchings for the Fine Art Society. In addition to these prints, he also created a large body of pastels, which also explored picturesque doorways, small canals, back alleys, private courtyards and interiors such as his Palace in Rags (Fig. 2), which is very similar to Sargent’s Venetian Interior (Fig. 3). Some art historians have suggested that both works are situated in the Palazzo Rezzonico where Sargent initially resided when he came to Venice in 1880.4 While there is no firm data that links Whistler and Sargent together during that period, they shared similar subjects and the same social circle. Their paths must surely have crossed at Casa Alvisi where Katharine Bronson, the first of the wealthy American expatriates, had settled in 1876. She quickly became known for her generosity as a hostess to artists of all nationalities, including Sargent and Chase, as well as for her support for the revival of the Venetian lace industry, which became a subject for many of the artists of the period, including Whistler and Sargent.5

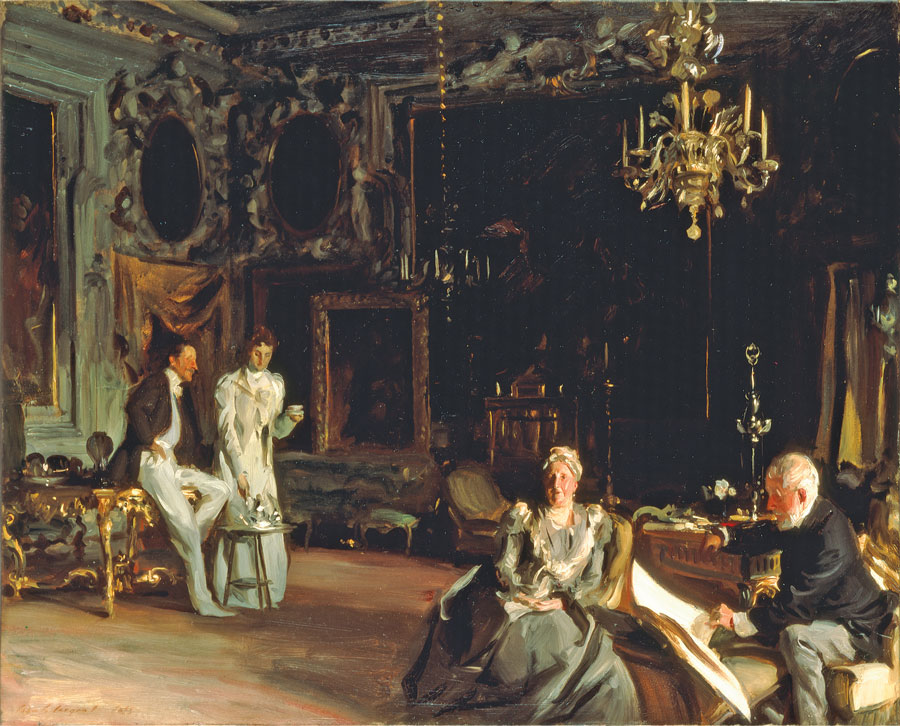

Sargent had greater entrée than his American artist contemporaries into the Anglo-American expatriate society as a result of his friendship with Ralph Wormeley Curtis. Curtis was a professional painter, but his artistic role has been overshadowed by his interaction with the artistic and social communities in Venice. Curtis’s parents, the socially prominent Bostonians Daniel and Ariana Curtis, rented the Palazzo Barbaro in Venice in 1881, and purchased it in 1885. It is where Sargent stayed during his second trip to Venice in 1881–1882, and many American artists were to frequent the Barbaro during the Curtis’s long residence there. The two had studied together in Paris under Carolus-Duran, and Curtis subsequently under Duveneck in Florence in the winter of 1880–1881. As one of the Duveneck boys, Curtis painted James McNeill Whistler at a Party in 1880 (Fig. 5), documenting a social event at Bronson’s Casa Alvisi. His own likeness is best recalled in Sargent’s depiction of Curtis, his wife, and his parents, An Interior in Venice (Fig. 6) painted in 1898 in Venice.

Though Cincinnati’s Robert Blum (1857–1903) had studied with Duveneck on the latter’s brief return to that city in the mid-1870s, he did not follow the master back to Munich. He was the American painter perhaps most often in the city during that decade.6 Among Blum’s best-known Venetian pictures are his views of the great palaces along the canals. Blum’s genre paintings offer a fascinating counterpoint to Sargent’s “black,” hermetic Venetian pictures of the 1880s. Though both artists painted local women engaged in the traditional tasks of bead stringing, Sargent’s dark and mysterious A Venetian Interior (Fig. 7) of circa 1880–1881 could not be more different from Blum’s Venetian Bead Stringers (Fig. 8), painted in 1887. In the same year Otto Bacher, one of Duveneck’s boys, wrote that ”Many of the poorer classes are engaged in the monotonous industry of stringing beads…In common with woman kind they are fond of dress where the taste can possibly be gratified and love of flashy gaudy colors is predominant.”7 This indeed, characterizes Blum’s treatment of the theme in its bright coloration and gaiety of color, in contrast not only to Sargent’s painting, but the etchings of the subject made by both Bacher and Whistler.

Over many decades and through numerous editions, the standard contemporary description of and guide to Venice had been William Dean Howells’s Venetian Life, published in 1866.8 The first illustrated edition appeared in 1892, with Venetian scenes by four American painters including Childe Hassam (1859–1935), represented by such works as his Feeding Pigeons in the Piazza (Fig. 9), a lovely, engaging touristic view, based on his only visit to the city in 1883.9 Another artist who participated in this project was Francis Hopkinson Smith (1838–1915), one of America’s leading watercolor painters of the late nineteenth century, who, from the 1880s on, made nineteen visits to Venice. Since Howells’s book was written while Venice was still under Austrian rule, it may be that this involvement encouraged Smith to produce his monumental, twenty-part series of large folios published in 1894–1895 to provide a more up-to-date account of the city, abundantly illustrated with his own watercolors, and later republished in a far smaller format with fewer illustrations as Gondola Days in 1897.10

Hassam’s single visit to Venice took place before he adopted the aesthetics of Impressionism, as was true of Theodore Robinson, and of the two trips John Twachtman made to the city. In fact, the great majority of the major American impressionists took little notice of Venice, the exceptions being two Bostonians, John Leslie Breck (1860–1899), who painted there in 1896–1897, and Maurice Prendergast (1858– 1924), whose beautiful Venetian watercolors were created in the summer of 1898 and on a return visit the following spring and summer. This was unlike the major French Impressionists—Edouard Manet was in Venice in 1875, August Renoir in 1881, and Eugene Boudin, during the last years of his life, made three visits to Venice between 1892 and 1895, while Claude Monet’s visit in late 1908, when he was invited to stay at the Palazzo Barbaro, is well known.11

Among the Anglo-American visitors were Isabella Stewart Gardner and her husband, Jack, who began coming to Venice in 1884, and in 1890 rented the Barbaro from the Curtises for a period almost every year, making five stays in all between 1890 and 1897. Mrs. Gardner purchased a number of works by contemporary Italian artists. Her first purchase was A Venetian Lagoon by Pietro Fragiacomo in 1884. The following year Ralph Curtis advised her to purchase Neapolitan artist Antonio Mancini’s major work The Standard Bearer of the Harvest Festival. In 1895, while staying at the Barbaro, Jack Curtis had his portrait painted by Mancini, a frequent visitor to Venice and a member of the Barbaro circle. The leading Swedish artist of the time, Anders Zorn, painted a portrait of Isabella Gardner standing in the window of Ralph Curtis’s studio in the Palazzo on her visit to Venice in 1894. Ludwig Passini, born and trained in Vienna, and dividing his time between Berlin and Venice, was one of the artists most involved in the expatriate circle, painting portraits of Katharine Bronson and her daughter Edith, as well as of Isabella and Jack Gardner when they were in Venice late in 1892, and also of Sir Henry Layard, who was, with his wife, Enid, the most prominent of the English expatriates.

Unlike other large cities in Italy, Venice did not produce its first major art exhibition until 1887. The Esposizione Nationale Aristica Venezia was held in the Public Gardens, and was a predecessor to today’s Biennales, which began in 1895. Though ostensibly limited to Italian artists, the 1887 show included work by four Americans: Sargent, Curtis, Eugene Benson, and Paul Tilton; with Sargent, Curtis, and Antonio Mancini listing the Palazzo Barbaro as their residence at the time.12 The “hit” of the Exhibition was Ettore Tito’s The Old Fish Market at the Rialto (Fig. 10). Tito was one of the Venetian painters most involved with the Barbaro set and especially with Isabella and Jack Gardner; he made numerous caricatures in Isabella’s guest-book, and in December 1895, Jack Gardner recorded having lunch with Tito and Antonio Mancini. But details of interactions between the American artists and patrons and their Venetian counterparts are few.

With the establishment of the Biennale in 1895, Venice, strangely, seems to have lost some of its appeal as an international art colony, and with the development of new hotels, and its promotion as a resort, it became a destination for tourists rather than artists. Artists continued to visit, but they were more interested in its successive international exhibitions than in the city as a place in which to paint. The wealthy but aging expatriate class became less involved in the artistic affairs of the community; indeed, Katharine Bronson died in 1901.

Sargent was an exception. He returned to Venice in 1902 and visited almost every year through 1913, where he produced a large body of watercolors including the Piazetta buildings facing the water, the palaces and boats on the canals, and especially of Santa Maria della Salute, all dashed off with unparalleled vigor. Sargent’s thematic choices were based on those views that could be painted from his gondola studio, and thus the great Cathedral of St. Marks appears only peripherally in such watercolors as The Piazetta with Gondolas (Fig. 11) of 1911. His unique approach becomes obvious when compared to traditional head-on depictions of St. Marks from Whistler through Prendergast and Englishman Walter Sickert, evidenced by Sickert’s St. Mark’s Venice (Fig. 12) of 1895–1896.

While Venice continued to draw able English watercolorists who provided excellent tourist views of the city, Sickert and Frank Brangwyn were the two primary British artists in residence in Venice after the turn of the century, remnants, with Sargent, of the vigorous artistic international colony that had thrived there in the previous generation. Sickert first visited in 1894 but spent 1903–1904 back in the city, while Brangwyn was in Venice at the same time as Sargent in 1907, supervising the installation of his murals in the British pavilion of the Biennale. Sickert, with his vigorously painted but traditionally composed views of the Salute and St. Marks had little use for Sargent’s “slap dash gouches [sic],”13 which today are unrivaled both in the history of watercolor painting and in a record of early twentieth century Venice.

The exhibition Sargent’s Venice was held at Adelson Galleries in New York, January 19 through March 3, 2007, and at the Museo Correr, Venice, from March 24 through July 22, 2007; the latter was the first solo exhibition of the artist in Venice. An accompanying book by the same title from Yale University Press is available wherever books are sold. For more information visit www.adelsongalleries.com or call 212.439.6800.

-----

William H. Gerdts is professor emeritus of art history at the Graduate School of the City University of New York. His article, “American Artists in Sargent’s Venice: An International Milieu,” is published in Sargent’s Venice (Yale University Press, 2006).

This article was originally published in the 7th Anniversary issue of Antiques & Fine Art magazine, which is affiliated with Incollect.com. The entire digitized verrsion of the issue is available on www.afamag.com.

2. The first publication to highlight Twachtman’s Venetian achievement is the recently published book by Lisa N. Peters, John Twachtman (1853– 1902) A “Painter’s Painter.” New York, Spanierman Gallery, L. L. C., 2006. See also Peters’s earlier “Twachtman: A `Modern’ in Venice,” in Irma Jaffe, ed., Insights and Inspiration II: The Italian Presence in American Art: 1860–1920 (New York, Fordham University Press, 1992), 62–81.

3. The primary study of “The Duveneck Boys” is Elizabeth Wylie, Explorations in Realism: 1870–1880. Frank Duveneck and his Circle from Bavaria to Venice. (Framingham, Massachusetts, Danforth Museum of Art, 1989); it is a subject that deserves further scholarly study. For Duveneck’s own work in Venice, probably the best source is Michael Quick, An American Painter Abroad: Frank Duveneck’s European Years. Cincinnati (Cincinnati Art Museum, 1987).

4. For Whistler’s stay in Venice see especially Alastair Grieve, Whistler’s Venice (New Haven and London, Yale University Press, 2000); Margaret F. MacDonald, Palaces in the Night. Whistler in Venice (Berkeley and Los Angeles, University of California, 2001); Erik Denkler, Whistler and his Circle in Venice (London and Washington, D. C., Merrill, in Association with the Corcoran Gallery of Art, 2003).

5. The pictorial (and photographic) images of lace making in Venice are legion. For Bronson’s involvement, see Catherine Cornaro [Katharine Bronson], “The Revival of Burano Lace,” Century Magazine, 23 (January, 1882): 333–343.

6. The definitive study of Robert Blum, unfortunately unpublished, is Bruce Weber, “Robert Frederick Blum (1857–1903) and his Milieu” (Ph. D.

dissertation, Graduate School of the City University of New York, 1985).

7. William A. Andrews, Otto Bacher (Madison, Wisconsin, Education Industries, Inc.), 1973.

8. William Dean Howells, Venetian Life (New York, Hurd and Houghton, 1866); new edition With Illustrations from Original Watercolors [by Childe Hassam, Ross Turner, Rhoda Holmes Nicholls, F. Hopkinson Smith], 2 vols. (Boston and New York, Houghton Mifflin and Company, 1895).

9. All of Hassam’s illustrations for Howells’s volumes may not be directly transcribed from the watercolors he made in 1883, since a number of them are painted in a very dashing and colorful Impressionist mode that Hassam did not adopt until the end of the decade. These may be eworkings of some of his earlier watercolors.

10. F. Hopkinson Smith, Venice of To-Day (New York, H. T. Thomas, 1896); Smith, Gondola Days (Boston and New York, Houghton Mifflin and Company and Cambridge, Massachusetts, The Riverside Press, 1897). Smith had previously devoted four chapters to Venice in Well-Worn Roads of Spain, Holland, and Italy (Boston and New York, Houghton Mifflin and Company, Cambridge, Massachusetts, Riverside Press, 1887).

11. Monet’s three month stay in Venice has received a good deal of attention. See Philippe Picquet, Monet et Venise (Paris, Herscher, 1986); Joachim Pissarro, Monet and the Mediterranean (New York, Rizzoli, 1997).

12. Espozione Nazionale Artistica Venezia 1887 Catalogo Ufficiale (Venezia, Prem. Stab. Tipo-Let. Dell’Emporio, 1887).

13. Sickert had little use for Sargent’s work generally, as he expressed in his article “Sargentolatry,” The New Age (7, May 19, 1910), 56–57. Although their stay in Venice overlapped in 1904–05, Sickert by that time had become less enthusiastic about recording the architecture of Venice, which was commanding Sargent’s attention, and was turning more and more to indoor figure painting.