Villains in Power and Freedom From Tyranny: The Magna Carta, the American Revolution, and Massachusetts

On June 15, 1215, in a meadow near London, England, known as Runnymede, a group of rebellious English barons forced King John to agree to a document that, eight hundred years later, remains one of the symbolic foundations of liberty, freedom from tyrannical rule, and the rule of law. Magna Carta (Latin for “Great Charter”) protected the barons against the king’s violation of many of their traditional rights as Englishmen, privileges that they believed King John was trampling upon capriciously.

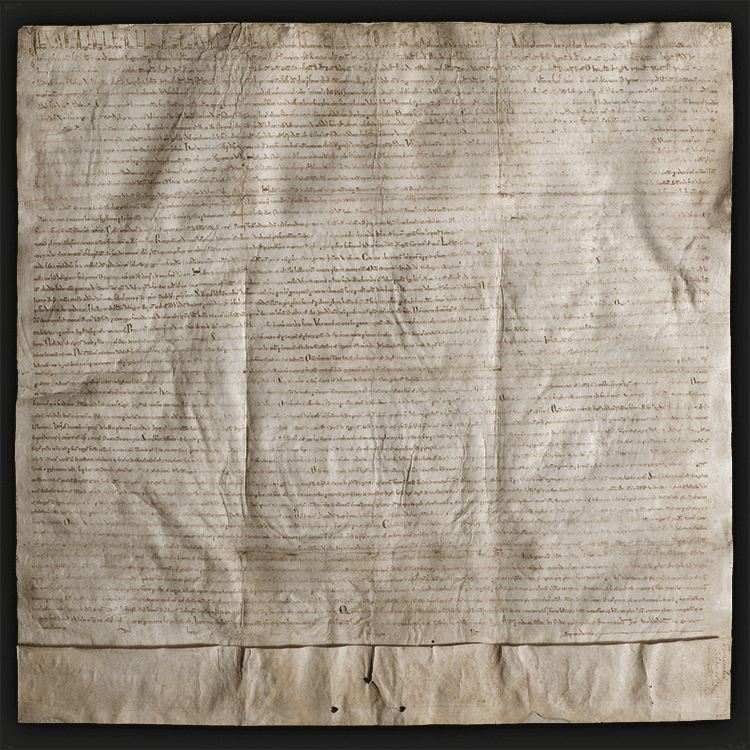

A powerful symbol of human rights and freedom from tyranny, Magna Carta is, surprisingly, an unassuming object itself, lacking calligraphic embellishments and images. Its nearly four-thousand Medieval Latin words, written on parchment (sheepskin), are organized into sixty-three clauses, many of which relate to specific concerns of the thirteenth century, like taxes, inheritance, and the powers of the king. (One even specifies that no person or town can be compelled to build a bridge across a river.) Two clauses—numbers 39 and 40—remain as the foundation of such liberties as due process and trial by jury.

Repudiated by King John (still widely regarded as perhaps the worst English king of all time) within months, Magna Carta had to be revived and reinterpreted throughout the thirteenth century. In all, some two dozen examples of the issues of 1215, 1216, 1217, 1225, 1297, and 1300 survive, including one just recently discovered in an English county archive.

Lincoln Cathedral’s Magna Carta (Fig. 1) is one of only four extant copies (called “exemplifications”) of the official 1215 issue. (At least forty were prepared by the royal chancery.) Originally it bore a wax seal, now lost, indicating the king’s assent to its terms. This copy has remained in the collection of Lincoln Cathedral since its terms were decided upon at Runnymede, and was on loan last summer for a special exhibition at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. It has recently been housed in a magnificent new facility in Lincoln, and has played a prominent role in the many anniversary activities surrounding Magna Carta.

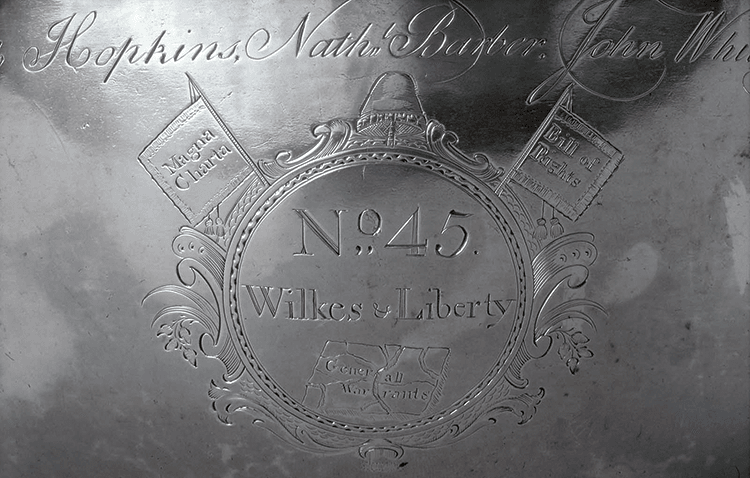

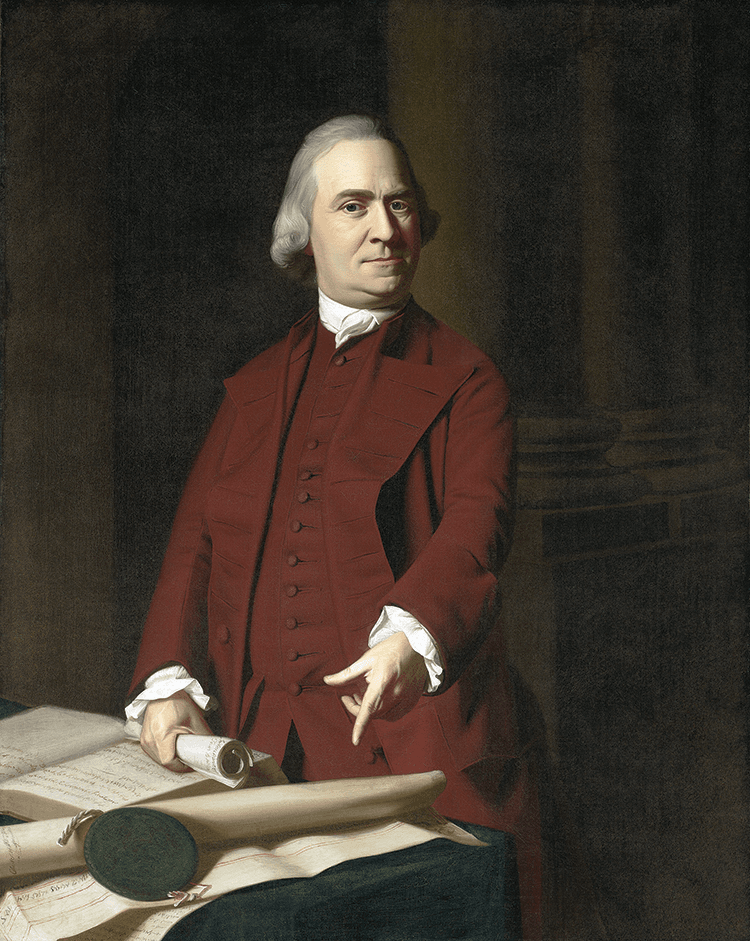

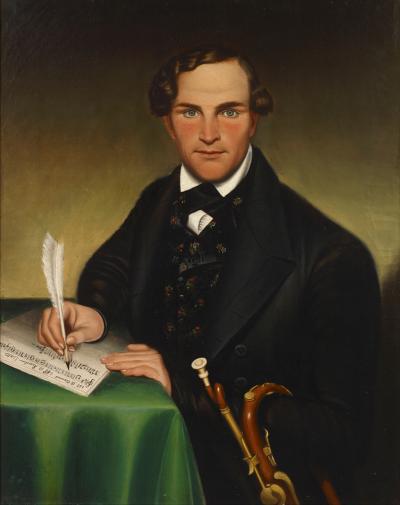

Magna Carta’s importance was revived in the seventeenth century in England, and it formed the cornerstone for the English Bill of Rights, adopted in 1689. By the mid-eighteenth century, Magna Carta was in the forefront of the minds of the American colonists, for whom it was a living, potent document. Patriots in Massachusetts believed, for example, that the principles it embodies and ensures were being violated by the English monarchy. Additionally, Paul Revere’s Liberty Bowl (Fig. 2) includes many references to symbols of liberty, including a flag engraved “Magna Charta” (Fig. 2a), as the document was called at that time. Samuel Adams (Fig. 3) believed that the Massachusetts Charter of 1691 was “as sacred [to Bostonians] … as Magna Carta is to the People of Britain.” It was the essential precursor to the rights asserted and protected in the Declaration of Independence, as well as in the United States Constitution and its own Bill of Rights, and was referenced repeatedly by the Founding Fathers, including Thomas Jefferson and John Adams (Fig. 4).

As the nineteenth century progressed, the guarantees promised by Magna Carta were applied to a widening circle of citizens, as is the American fashion. Paul Cuffe (or Cuffee), the free son of a West African father and Native American (Wampanoag) mother, was a Quaker mariner from Westport, Massachusetts (Fig. 5). In 1780, on behalf of the former slaves of Dartmouth, he and his brother John petitioned the Massachusetts General Court to give African Americans and Native Americans the right to vote or, failing that, to stop taxing them without representation. Citing the Revolution and echoing the liberties ensured by Magna Carta, the Cuffes argued that “many of our colour … have cheerfully entered the field of battle in the defence of the common cause … against a similar exertion of power [in regard to taxation].” Their petition was unsuccessful, but the Massachusetts Constitution of that same year would soon be interpreted as giving equal rights and privileges to all male citizens of the state.

In 1781, Theodore Sedgwick, a young lawyer on his way to a distinguished career as a Massachusetts attorney and politician, argued successfully in the trial of Brom & Bett v. J. Ashley Esq., that his clients Elizabeth Freeman, often known as Mumbet (Fig. 6) and “Brom” were not the property of the defendant, John Ashley. Citing the new Massachusetts Constitution of 1780 (drafted by John Adams) and its Bill of Rights, which asserted that all individuals were born “free and equal, and have certain natural, essential, and inalienable rights,” Sedgwick and his fellow lawyer Tapping Reeve convinced the jury that Mumbet and Brom should not be returned to Ashley but should be freed. Sedgwick later became a justice of the Supreme Judicial Court, which played an essential role in ending slavery in Massachusetts.

The link between Magna Carta and the governing principles of the United States has remained so strong that, following the assassination of President John F. Kennedy in 1963, the British government erected a monument in his memory at Runnymede. Today, Magna Carta is still cited by politicians, legal historians, judges, and others as the ultimate source of protection against arbitrary rule and what Paul Revere’s Liberty Bowl refers to as “the insolent menaces of villains in power.” Its powerful symbolic significance has been extended to many issues pertaining to equal rights under the law, for women, immigrants, enslaved peoples, and many others as its legacy continues in the twenty-first century.

Gerald W.R. Ward is the Senior Consulting Curator and the Katharine Lane Weems Senior Curator of American Decorative Arts and Sculpture Emeritus, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, and is also serving his second term as a State Representative in New Hampshire. He was the Museum’s curator for the exhibition “Magna Carta: Cornerstone of Liberty,” held July 2–September 1, 2014, and organized by the MFA in partnership with the Massachusetts Historical Society and Lincoln Cathedral. The exhibition was also generously supported by the Commonwealth of Massachusetts. He is grateful to Patrick McMahon, Peter Drummey, and Anne Bentley for their assistance with the exhibition.

This article was published in the Autumn 2015 issue of Antiques & Fine Art magazine, a digitized version of which is available onAFAmag.com. Antiques & Fine Art and AFAmag are affiliated with InCollect.com.