Matchsafe Mysteries Illuminated

A WINTERTHUR PRIMER

Recent efforts to identify elephant tusk ivory in Winterthur Museum’s decorative arts collection led to a modest, unadorned box, which appeared to be made of the material. The box is fastened by tiny nickel silver pins and has two short ends that pivot open (Figs. 1, 2). The box is palm-sized with a smooth, dry interior designed to safely hold phosphorus-tipped matches.1 Matchsafes, later also called match boxes or Vesta boxes, were portable containers for small numbers of matches that were sold by merchants in a gross (144), or larger quantities.2 Today we are accustomed to pocket match books or larger boxes of loose wood matches, but, by the mid-nineteenth century when friction matches were perceived a necessity of daily life, matchsafes became the norm.

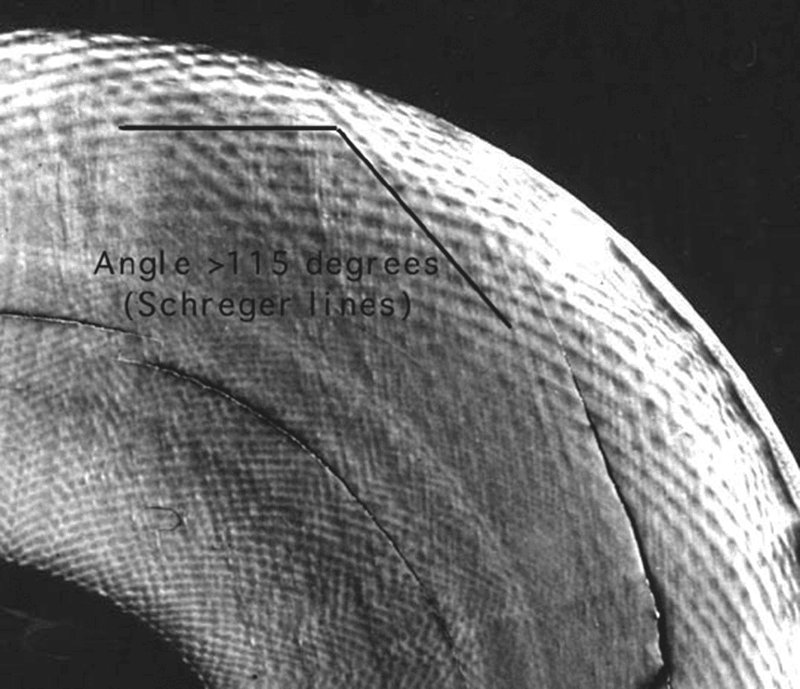

Matchsafes made in Europe and North America survive in durable and precious materials, often the locus of artistic design and ornamentation that wonderfully embellished or disguised their protective functional role.3 This smooth anonymous box, however, offered few clues for its origin or ownership history. To discover more, we asked: “Is it ivory?” and, “what is the dark brown material used for the striker?” Becky Kaczkowski, Winterthur/University of Delaware conservation student, began by visually determining the box material was ivory rather than celluloid or bakelite. She did this in part by looking for the intersecting growth lines (Schreger lines) and cloud patterning unique to elephant ivory, which was present on the box sides and ends (Fig. 3), and by using long-wave ultraviolet light, which causes ivory to fluoresce brightly, unlike synthetic materials.4

To understand the dark striker (Fig. 4), that did not look like the expected worn sandpaper, Ms. Kaczkowski used a variety of analytical tests. Examining a very tiny sample with Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) and gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC-MS), she detected an early form of thermoplastic. (Daguerreotype collectors may recognize a thermoplastic material used for original cases post-dating Samuel Peck’s 1856 invention.) The material is a molded shellac imbedded with gritty particles (wood flour) useful for igniting a friction match. The X-Radiograph image (Fig. 5) clearly shows how the striker and ivory strip supporting it have bowed inward from steady use.

Friction matches and matchsafes were imported by jewelers and merchants as well as manufactured in many states by the time of the Civil War, thus identifying the origin of this ivory box is difficult. Ivory is much rarer than silver, base metals or other materials, but in the late 1800s when ivory seemed plentiful, matchsafes were advertised as sets with ivory cigar cases and holders. The identification of the box’s thermoplastic striker—evidence of adapting the newest technological invention of its time—supports an attribution for American-manufacture.5 Today this matchsafe is displayed in Winterthur’s nautical-themed Counting Room, joining other items made from ivories and exotic materials once deemed necessary in North American culture.

An early appreciation for the novelty of friction matches was captured in 1846 with a droll poem, “Old Times and New” by a Boston lawyer Allen C. Spooner, published repeatedly in American newspapers. The reposing narrator describes his cigar-smoke infused vision of a Mayflower pilgrim ghost suddenly joining him at a cozy fireside:

“…I then took up a bit of stick,

One end was black as night,

And rubbed it quick across the hearth,

When lo, a sudden light!

My guest drew back, uprolled his eyes,

And strove his breath to catch —

‘What necromancy’s that,’ he cried —

Quoth I, ‘A friction match.’”

Ann Wagner is associate curator of decorative arts, Winterthur Museum, Garden & Library, Winterthur, Delaware.

More Winterthur Primer articles are available on Incollect. Visit www.Winterthur.org for a full listing.

This article was originally published in the Summer 2015 issue of Antiques & Fine Art magazine, a digitized version of which is available on afamag.com. Antiques & Fine Art, AFAmag, AFAnews, and AFA Publishing are affiliated with InCollect.com.

2. The earlier term matchsafe was commonly adopted by the 1840s to refer to small boxes (approximately 2 ½ inches long) containing friction matches.

3. For further research, see the extensive collection of matchsafes at Cooper-Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum, some of which are published in Deborah S. Shinn, Matchsafes (Smithsonian Institution, 2001).

4. See Edgard O. Espinoza and Mary-Jacque Mann, Identification Guide for Ivory and Ivory Substitutes, (Washington, DC: World Wildlife Fund and Traffic, 2000). Additionally, irregular cracks in ivory caused by temperature and humidity change over time appear differently than the surface cracks and crazing on modern materials and fakes.

5. For a similar matchsafe, see: Cooper-Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum, 1980-14-1289. In 1878 an ivory cigar set was presented to a steamship captain (inauspiciously named Captain H. H. Drown) and engraved with his monogram. Online source: Cincinnati Daily Gazette (February 11, 1878), 7.