Maven of Modernism: Galka Scheyer and the Blue Four

Every artist needs a champion. For Yves Klein, it was Pierre Restany. For Jackson Pollock and practitioners of Abstract Expressionism, it was Clement Greenberg. And, for the “Blue Four”—Lyonel Feininger, Alexei Jawlensky, Paul Klee, and Wassily Kandinsky—it was a gregarious Jewish emigré from Braunschweig, Germany.

A new exhibition at the Norton Simon Museum, in Pasadena, Calif., tells the story of Galka Scheyer (1889-1945), a California-based dealer who was a lifelong proponent of modernism and is credited with establishing a market for the Blue Four by arranging exhibitions, lectures, and publications, as well as negotiating sales on behalf of the group. Along the way, Scheyer helped solidify California’s status as a hub of modern art and gathering place for avant-garde artists from across the world. The new show, “Maven of Modernism: Galka Scheyer in California,” includes a number of examples from her private collection, which was donated to the Pasadena Art Institute in the early 1950s. Taken together, the exhibition is a snapshot of California at a time of creative ferment, when practitioners of modernism converged in the state to negotiate the next phase of the movement.

Galka Scheyer was born Emilie Esther Scheyer in a middle-class Jewish family in Lower Saxony. She studied piano and painting as a young woman but discovered a new vocation after seeing some paintings by Jawlensky at the 1915 “Exhibition of Contemporary Russian Artists,” in Lausanne, Switzerland. (It was Jawlensky who nicknamed her “Galka,” the Russian word for jackdaw, or an inquisitive crow.) Before long, Scheyer had befriended all four members of what became the Blue Four and, on March 31, 1924, she signed a deal with the group to “spread their artistic ideas abroad, especially through lectures and exhibitions.” (The name “Blue Four” is a riff on “Blaue Reiter,” a branch of German Expressionism.) Scheyer settled in California in 1925.

Thus, Scheyer became an evangelist for the four artists, arranging events in Los Angeles, San Francisco, and elsewhere. Before long, she came to be regarded as the doyenne of modernism, a friend to Imogen Cunningham, Edward Weston, Frida Kahlo, Diego Rivera, John Cage, Walter and Louise Arensberg, Josef von Sternberg and Peter Krasnow.

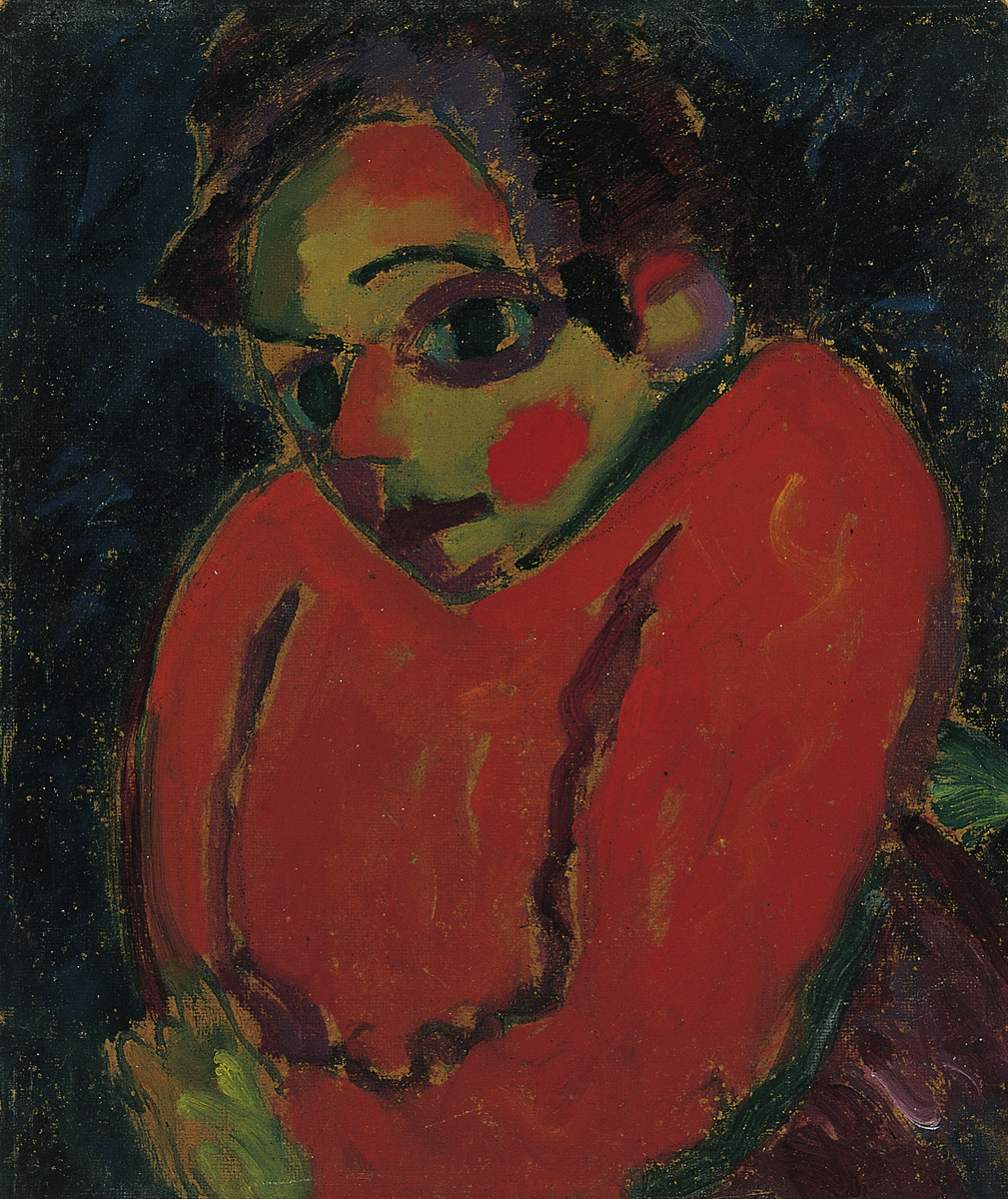

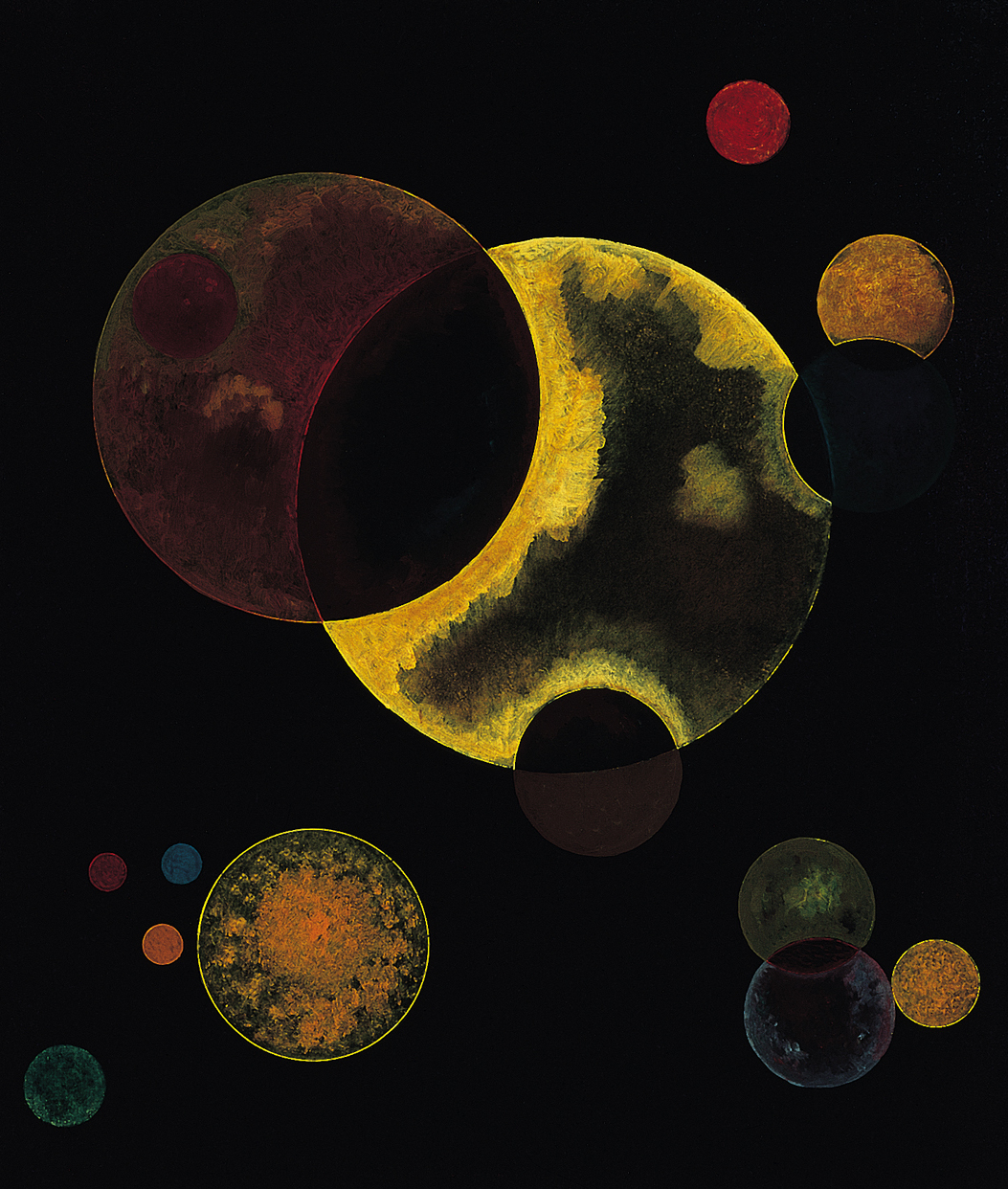

Many of the works on view at the Norton Simon Museum were given to Scheyer in appreciation of her patronage and speak to the close bond between the dealer and members the Blue Four. Jawlensky’s The Hunchback (1917), which shows a youthful figure with rosy cheeks and a bashful expression, was given to Scheyer by the artist and is based on a work she saw at the 1915 exhibition in Lausanne. In similar fashion, Kandinsky’s Heavy Circles (1927), a symphony of circles suspended in ether, was presented to the dealer by Kandinsky as a gesture of friendship. Klee’s Possibilities at Sea (1932) was so admired by Scheyer that she negotiated its purchase from the artist, proclaiming, “It is one of the most amazing pictures I have ever experienced.” And, finally, Feininger’s Untitled (1945), a crudely rendered cityscape under a crescent moon, was given to Scheyer by the artist after he learned of her diagnosis of cancer, writing, “It is enough to make one want to shed tears, when we think of you suffering, with your deep love for Art the only thing that keeps your chin up.”

“Maven of Modernism” was organized by Curator Gloria Williams Sander and will be on view at The Norton Simon Museum until September 25, 2017. For more information, call http://www.nortonsimon.org/.

For more articles on Abstract Expressionism, see:

D. Wigmore Fine Art Spotlights Abstract Expressionist Paul Jenkins, A Master of Color and Flow

Calder and Abstraction: From Avant-Garde to Iconic

Make it New: Abstract Painting from the National Gallery of Art, 1950–1975