Modern Classicism: The Art of Will Barnet

This archive article was originally published in the Autumn/Winter 2007 issue of Antiques & Fine Art magazine.

Seated at his studio worktable, Will Barnet swivels to study photographs of seven of his paintings, laid out carefully side-by-side for comparison. He is clearly elated. They are assembled with the assistance of Robert Yahner, Will’s studio curator. “Nothing makes me happier than seeing the series displayed this way,” says Will, “unified in the way they relate to each other and their development.”

The progression, beginning with the abstract Big Duluth (1960) and concluding with the figural Three Chairs (1991–1992) is a flawless illustration of the coalescing force connecting works done throughout thirty of his eighty-plus years of painting. The lines, the vertical climbs, horizontal stretches, forms, organization, architectural, and structural elements echo from one work to the others. They are interior landscapes, whose tension and stillness are vital and musical; these paintings are, as Will once described them, “a world in a frame, and the whole world is contained within that frame, not part of the world, the whole world.”

Influenced and inspired by the works of Ingres and Vermeer, Will admits to a fascination with the scope of Vermeer’s paintings. “Vermeer takes a corner of a room and makes the world out of it. If you take one little piece out of a Vermeer painting, you’ve ruined it completely. He goes right to the edge.” And Will prides himself in following suit. “I’m not going against the grain of history; I’m going with it. But I’m adding new dimensions by the way I abstract. And my paintings are not psychological; they’re straight from humanity.”

Will approaches a figurative painting with the same conception as an abstract. They share the same values and express Will’s regard for humans, whether through intimate relationships or broader ones. During the 1960’s, Will felt that representational art was—for him—too obvious. He wanted a more modern reorganization of the physical aspects of the canvas, which was flat and two-dimensional. And he found the work of “realistic” painters to be photographic, highlighting background and perspective. “I don’t think that way at all,” he said, “My work is both visual and conceptual at the same time. What I see seems to spread out, move vertically and horizontally. It has a different position as it moves through the space, and these shapes and forms are configuring a human image, which is reorganized according to the painting, rather than what I see. It’s a transformation from reality to the reality of the canvas.”

Environment and his home life are crucial elements in any Will Barnet painting. Will finds inspiration in events taking place immediately in front of him, rather than in something imaginary. Environment begins the process, the idea, the development. The human figures add a tension and excitement to the pieces. “Tension is very important in my work. And quietness. Without tension, the piece is not alive; it becomes decorative. And it’s not decorative; that’s very important to me.”

Big Duluth (Fig. 1), the abstract in the progression, was created during a period when Will was traveling and exploring the vistas of the Great Lakes. After a residency at the University of Minnesota in Duluth (summers of 1958 and 1959), he was artistically fired by the great landscapes, the night skies and different spheres to be seen at midnight, the colors of the darkness and the density of the water at Lake Superior.

In Will Barnet: Painting without Illusion, Patrick J. McGrady, the Charles V. Hallman Curator at the Palmer Museum of Art, relates that Big Duluth was a turning point for Will. “Barnet derived most of his compositions from the human figure. For the longest time, landscape had bewildered him.” He explains the genesis here of the linear sequence common to all seven paintings: “the arrangement of the abstracted forms facilitates a movement quite distinct. . . .Glowing in chromatic harmony with the disc that heads the painting, this (leg of the form furthest below) disperses the energy with an acute linear deflection to the right and, like its counterpart, out away from the picture plane as well.”

In a 1962 exhibition at the Bertha Schaefer Gallery, Will showed a new direction, on the heels of so many abstracts, when he premiered Mother and Child (1961) (Fig. 2). He explained the painting’s relevance to his body of work in a press release: “There is no ambivalence for me in the fact that the figure has been profoundly transformed, or transposed, with closer reference to its original structure. Nor are there any so-called ‘humanistic’ revelations for the present shift in my work.”

“My interest has been in developing further the plastic convictions which have been evolving in my abstract work; so that a portrait, while remaining a portrait, should become in this sense an abstraction: the idea of a person in its most intense and essential aspect.”

Again Will continued his sweeping lines within the forms, as described by Patrick McGrady: “…nearly all of the painting’s energy initiates near the upper right, with the mother’s left arm. Moving across, the horizontal force lifts slightly at the shoulder, dislodging the head as the weight transfers, where cheek meets hand, diagonally through the right forearm.”

Will’s intent in Mother and Child was to portray a modern Madonna. Modeled on his wife, Elena, and his daughter, Ona, the concept of the child and mother as separate is important. The child is not cuddled; she is an individual within her own orbit. Her raised arm divides her from her mother giving her a freedom, which was an important psychological point for Will—very different from the Old Masters whom he reveres.

“There is a spatial feeling,” says Will, “up and across, up and across. They blend into each other, connect. They’re like iron and steel. I want my painting to have weight and strength. But notice that they’re flat; they don’t try to give you any perspective. You read them as you move around.”

The Blue Robe (1962) (Fig. 3) again conforms to the established composition. Patrick McGrady captures the correspondence: “Although nearly square (just four inches wider than tall), the painting feels abundantly horizontal, due in a large part to the accentuation of the three underlying rectangular bands at each juncture by limbs stretching in either direction. The woman’s right arm is especially dynamic, reaching from as far back as her left shoulder across the entire width of the canvas. Together with the equally forceful weight of her left arm, which anchors the entire right side with the resolve of a Doric column, the woman outlines the parameters of the painting’s action.” Will believes that the sense of movement and excitement (although on a basic two-dimensional plane) gives the painting its tension and passion.

Will’s affinity for Italians, and in particular the Italian film “L’Aventura,” created the concept for Sleeping Child (Fig. 4), where a woman (possibly, he thinks) modeled after Anna Magnani exerts a physical presence through the use of her arms. “The painting is not about the costumes,” says Will, “even though the robes add the form. Elena was combing her hair one day, and I made a lot of drawings. This painting is a synthesis of many of those drawings. The way the arm comes up and crosses over—it continues that line we’ve spoken about in this series; all these paintings have the same context. The scale is distorted. That’s what Ingres did all the time. He would take tremendous liberties with the form underneath before he’d finish a painting. I have taught generation after generation that in the Old Masters’ paintings realism covered abstraction.”

The deep moods, poetic elements, musicality, line, elegance and strength of a Will Barnet work are as noteworthy as its absence of melancholy. While reflective, the paintings are peaceful.

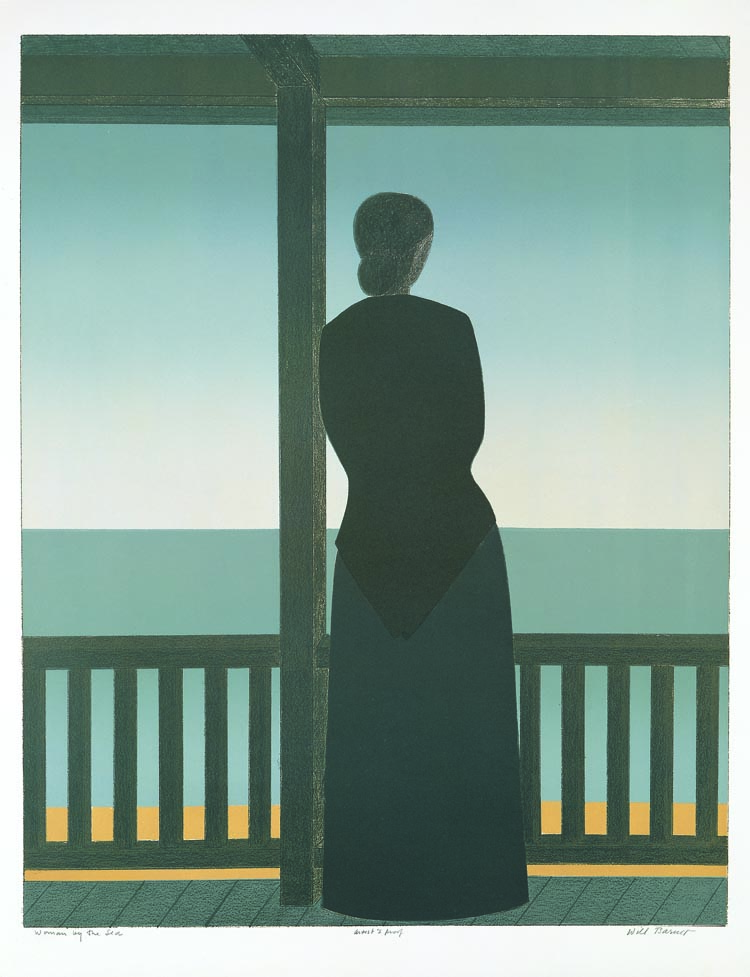

Will’s pallet is continually reinvented, with the creation of a new color taking days. The brilliance and significance of his vivid hues is never more evident than in the Maine series. Woman and the Sea (1972) (Fig. 5) is a perfect illustration of Will’s use of color to stimulate mood. Gail Stavitsky, curator of two of Will’s shows at the Montclair Art Museum, writes in her book, Will Barnet: A Timeless World, that “The subtly simplified figure—evocative of Seurat’s women—is imbued with a sense of strength, grace, monumentality, and universality that is anchored by the strong perpendicular organization of the porch architecture, contrasting values of light and dark, as well as the horizon…. A specificity of time and place is suggested by the cool greys and weighty blues of Maine, as well as the solitary figure’s scarf shielding her from the coldness of the sea and the atmosphere.”

In Stavitsky’s commentary on Early Morning (1972) (Fig. 6), with its dazzling lemon yellow sky, she says “The small figure (Elena) is part of a total landscape/vista seen at another time of day as the morning light is just about to break. The radiant quality of light, subtle atmospheric effects, quietude, and vast, boundless space of this work suggest the impact of the 19th century luminist painters in America.”

Possibly the most difficult, and active, of the paintings in the series is Three Chairs (1991–1992), featuring Will’s wife, Elena; daughter, Ona; a grandson and granddaughter; and family pets. “I started out with three chairs, nobody in them,” he says. “I was thinking about what to do with them. I thought about having them be alone, without anybody. Sometimes it’s wild, you know, what happens. I put a figure in, then another, then others, and a dog and a cat. On Elena’s tapestry is a portrait of me. All of a sudden, it became a unified exciting imagery of three chairs being occupied by human beings and animals, with background and the structure of the porch. These are elements of nature.”

Will’s philosophical “Master” is Spinoza, who he is fond of quoting. “Spinoza said that there is only one God, and that is nature. And that’s what I believe in very strongly, nature. Who we are, where we come from, we don’t know. But I’ve worked all these years, each period with its own elements, but with a basic structure that Bob has assembled here. I consider it all figurative, even Big Duluth. It’s painting, and it’s Spinoza— nature and God. There they are.”

This article was originally published in the Autumn/Winter issue of Antiques & Fine Art magazine. AFA is affiliated with Incollect.