Modernism Meets Preservation: Katherine Warren in Newport

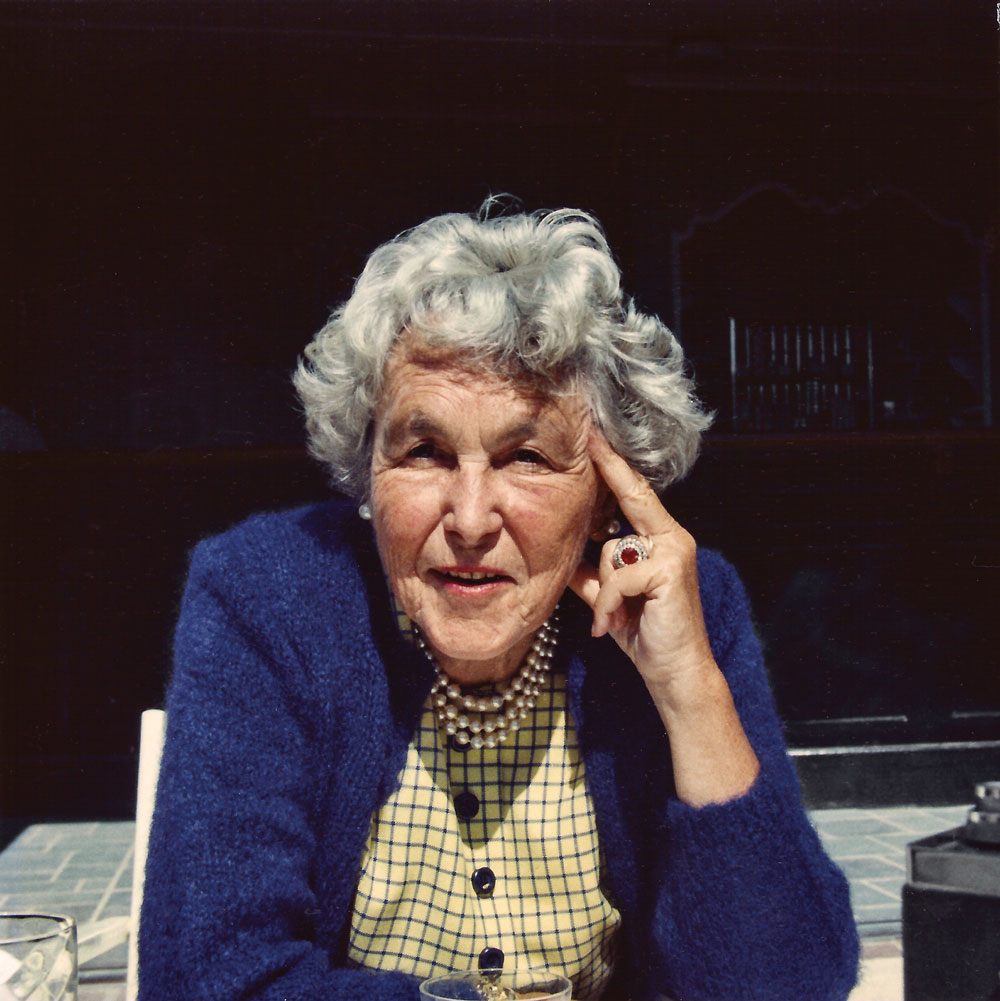

Newport, Rhode Island, is renowned as one of the most historically significant and architecturally intact cities in America. In the years following World War II, this heritage was under siege; post-war economic shifts threatened the city’s historic architecture with demolition and redevelopment. Spearheading the effort to protect Newport’s architectural heritage was Katherine Urquhart Warren (1897–1976) (Fig. 1). She sparked a movement that, over the course of the mid-twentieth century, preserved the full spectrum of the city’s architecture, from its unparalleled collection of colonial houses to its impressive Gilded Age mansions and everything in between. A founding member and the first long-time president of The Preservation Society of Newport County, Warren was masterful at striking a balance between safeguarding the city’s heritage and aiding modern development.

Warren achieved these ends by applying preservation techniques that were on the cusp of contemporary theory and, in many ways, ahead of their time. A forward-thinking approach was innate in Warren; not only was she a prescient preservationist, she was also a prominent patron and leader in the modernist art movement.

Warren’s personal art collection, which she began during the late 1920s, focused on early-twentieth-century European and American art, and encompassed textbook examples of the artistic developments emanating from cubism, including Dada, surrealism, De Stijl, and constructivism. She owned works by artists such as Piet Mondrian, Fernand Léger (Fig. 2), and Pablo Picasso at a time when their style was considered radical and their significance was vastly undervalued.

While Warren was advised in her collecting by friend and artist Albert Eugene Gallatin, her collection was a product of her own preferences. It was fun, she argued, “to follow the careers of those of [the] time who [would] be the Old Masters of a future day” (Fig. 3).1 Warren’s advocacy of modernist art led to her involvement in a number of arts and cultural organizations. Throughout the 1940s, she was an active member of the Art Association of Newport and periodically curated exhibitions for the museum.2 Simultaneously, she was a prolific donor and keystone of the leadership at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in New York City. She served on the museum advisory committee, board of trustees, and numerous subcommittees and ad hoc groups, becoming influential in the growth of MoMA during its formative years. Her involvement overlapped with renowned figures such as Abby Aldrich Rockefeller, one of the museum’s three founders, and Philip Johnson, founder of the museum’s department of architecture and design.3

Even after resigning from MoMA’s leadership in 1947, Warren maintained ties with the institution, serving on temporary museum committees and lending artwork to exhibitions. Of particular note was MoMA’s 1948 New York Private Collections exhibition, to which Warren loaned a painted wood relief by Jean Arp; bronzes by Constantin Brâncuşi and Gaston Lachaise; and paintings by Juan Gris, Paul Klee, Joan Miró, Piet Mondrian, and Pablo Picasso.4

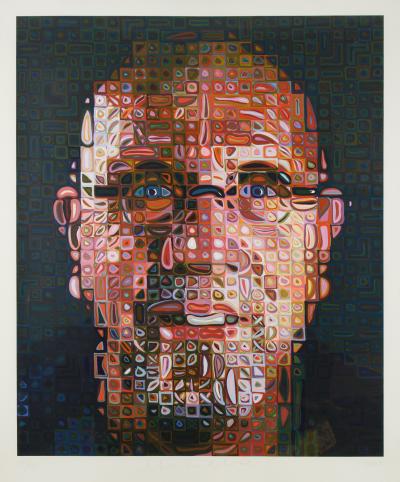

During the early 1950s, Warren became active at the Museum of Art at the Rhode Island School of Design (RISD), serving on the museum committee and RISD corporation for more than fifteen years collectively. She loaned artwork for exhibitions and donated various works, including a painted wood relief by Jean Arp, paintings by Joan Miró and Ilya Bolotowsky, and Woman in a Chair by Pablo Picasso.5 Warren grew to be a respected member of the RISD community and in 1983 the museum curated an exhibition in her honor (Fig. 4).6

Nationally, Warren was part of a small group of adventurous collectors who had the foresight and fortitude to collect contemporary art at a time when its significance and value could not have been anticipated and was, in fact, viewed with much skepticism. Rhode Island, in particular, was reluctant to embrace the modernist art movement. As late as 1968, the director of the Museum of Art at RISD explained that the institution’s “struggle to bring Rhode Island into the mid-20th century [continued] to go very slowly.” 7 Even her family was puzzled by her collection; they could not help but “wonder what she saw in them.” 8 Ultimately, Warren earned respect for her “far-reaching grasp” of the modernist art movement and “unerring eye for great works of art.” Contemporary critics praised her collection itself for being concentrated, specialized, and overall brilliant.9

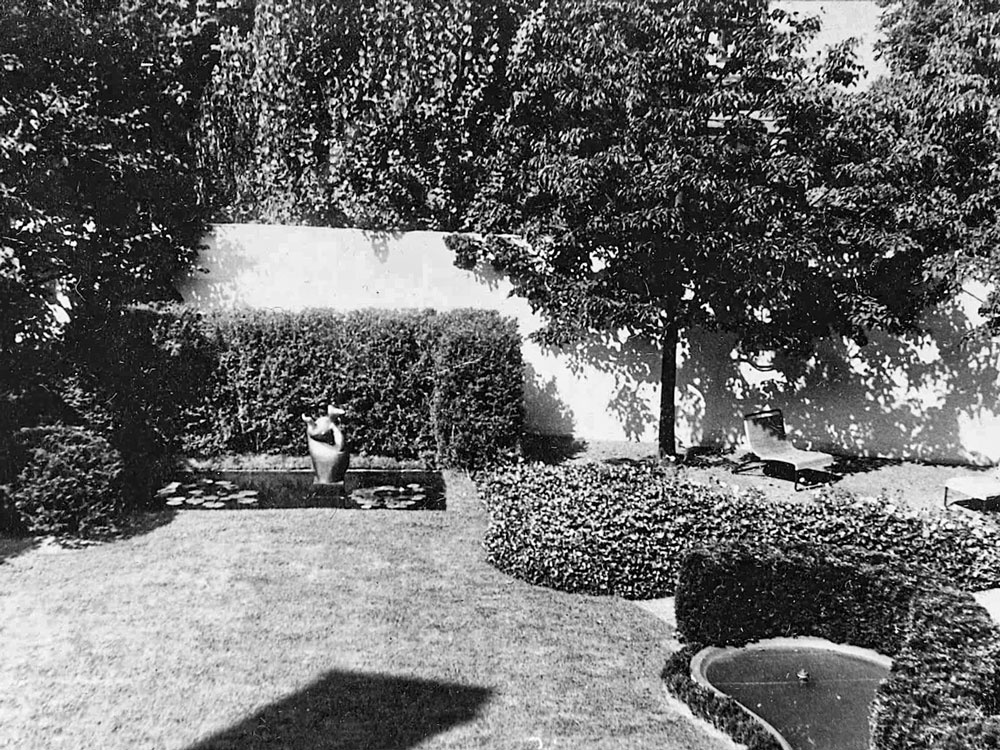

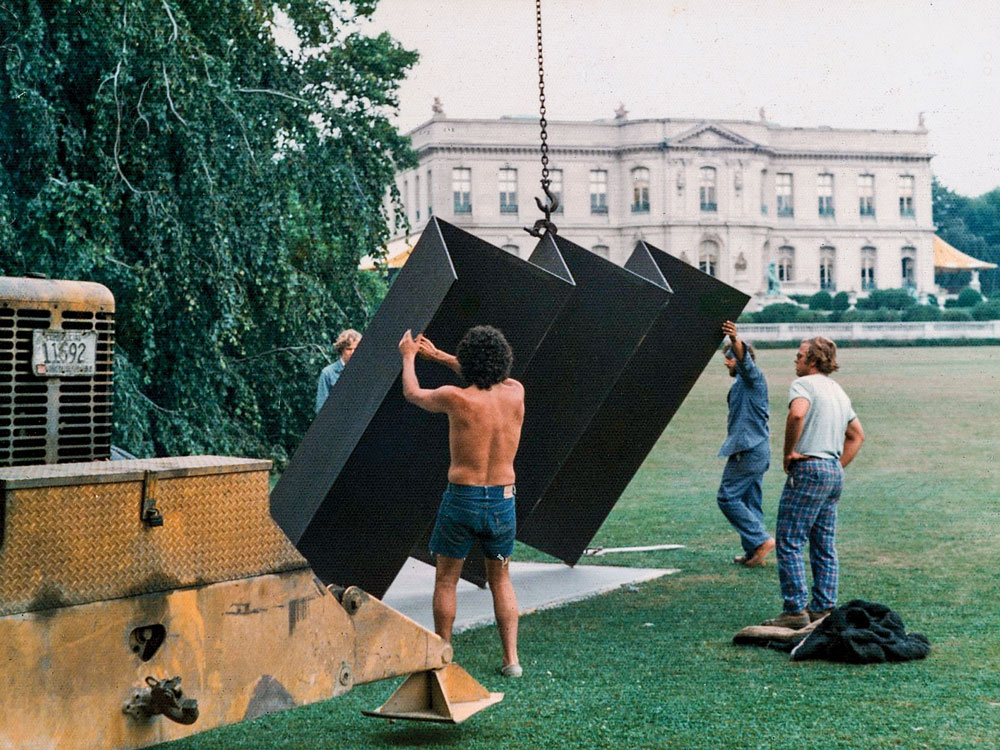

Warren’s passion for modernist art extended beyond fine art. In 1949, she commissioned the nation’s leading modern landscape architect, Christopher Tunnard, to design a garden for her Newport home. Today, it is considered a nationally significant and rare example of modern landscape design, possibly the only surviving commission by Tunnard in America (Fig. 5).10 Warren was also an active supporter of the first Newport Jazz Festival in 1954, when many residents were averse to the city’s “sudden status as a jazz mecca.”11 Similarly, Warren was a major proponent of Monumenta, an outdoor sculpture exhibition that opened in 1974 and featured artists such as Barnett Newman (Fig. 6), David Smith, and William de Kooning. While Monumenta received national attention, it was the victim of criticism and vandalism from the local community.12

Combined, Warren’s personal collection, involvement at various museums, and promotion of contemporary art forms reveal her as a leader in the modernist art movement.

She emerges as part of a larger, national story about the small group of individuals who expanded the public’s perception of modernist art. More tangibly, through her advisory roles and the works she donated, Warren shaped the future of the museums in which she was active as well as their audiences’ understanding of modernist art. In Newport, Warren’s fearless promotion of contemporary art extended the community’s breadth of artistic experiences and knowledge.

At first glance, Warren’s interest in both modernist art and historic preservation seems incongruous, as preservation is so often viewed as the antithesis of modernism. Even Warren acknowledged the complexity of her dual interests. She explained: “As much as I admire the beauties of the past, especially as represented by Newport’s sturdy little houses, which are so exactly right for their time and place, if I were to build a house now I would feel I must be true to my own time, and I would make it as starkly modern as possible. For there is no progress if we only copy the past.” 13 This embrace of the avant-garde shaped Warren’s preservation approach.

In Newport, she pushed the boundaries of contemporary preservation practice, shifting the local preservation paradigm from one that focused on colonial architecture, landmark protection, and house museums to one that embraced a broader range of architectural styles, the historic urban environment as a whole, and the vital role heritage played in the city. This ushered in a new era of preservation that influenced all subsequent efforts to protect and promote the community’s architectural heritage, making historic Newport what it is today.

From a national perspective, Warren’s approach in Newport did not mimic any one of the quintessential preservation examples at the time, such as Colonial Williamsburg or Charleston, South Carolina. Instead she drew from these communities and applied the practices and theories they represented in a new way. Warren also introduced ideas and approaches that were far ahead of their time. Her emphasis on protecting architecture in living memory, engaging the community, diverging from the museum model, and using preservation as a tool for economic and community revitalization all anticipated modern preservation ideals. Warren, as a result, emerged among the field’s pioneers as more than an equal, but as a thought-leader in twentieth-century preservation practice.

Warren viewed her historic preservation efforts in Newport as a “pioneer job” and believed that success could only be obtained through courage and vision.14 Conversely, she advocated that the city’s future would only be assured through its past.15 Warren’s marriage of heritage and modernism dispels the long-held misconception that the two are mutually exclusive and, moreover, that preservation is a barrier to change. Warren’s exemplary life and work are explored further in A Passion for Preservation: Katherine Warren and the Shaping of Modern Newport, written by Alyssa Lozupone and published by Applewood Books in cooperation with The Preservation Society of Newport County.

-----

Alyssa Lozupone is the preservation policy research specialist for The Preservation Society of Newport County and the author

of A Passion for Preservation: Katherine Warren and the Shaping of Modern Newport (2015).

This article was originally published in the Autumn 2016 issue of Antiques & Fine Art magazine, a fully digitized version of which is available on afamag.com. AFA is affiliated with Incollect.

2. Annual meeting minutes of the Art Association of Newport, 1940–1949, Newport Art Museum.

3. MoMA Press Release Archives, 1920–1997, Museum of Modern Art Online Archives,; “Katherine Warren, Founder of Preservation Society, Dies,” Newport Daily News (Newport, RI), 19 April 1976.

4. “Selections from 6 New York Private Collections,” 16 July 1948, MoMA Press Release Archives 1929–1997; Howard Devree, “Personal Choices,” New York Times (New York, NY), 25 July 1948.

5. Letter to Katherine Warren from Daniel Robbins, 8 February 1967, Mrs. George Henry Warren Jr. Papers; Letter to Katherine Warren from John Maxon, 16 December 1957, Mrs. George Henry Warren Jr. Papers; Letter to Katherine Warren from John Maxon, 20 May 1959, Mrs. George Henry Warren Jr. Papers. All papers in RISD Museum.

6. RISD Museum, Katherine Urquhart Warren Collection.

7. Letter to Katherine Warren from Daniel Robbins, 17 July 1968, Mrs. George Henry Warren Jr. Papers, RISD Museum.

8. George H. Warren (son of Katherine Warren) in discussion with the author, 19 September 2013.

9. Letter to Anne Urquhart from Stephen E. Ostrow, 20 April 1976, Mrs. George Henry Warren Jr.Papers and Katherine Urquhart Warren Collection, ii; RISD Museum.

10. David Jacques, Landscape Modernism Renounced: The Career of Christopher Tunnard (1910–1979) (New York, NY: Routledge, 2009), 174.; [Charles Birnbaum?], “Newport Discoveries: A Rare Christopher Tunnard Garden Reappears,” The Cultural Landscape Foundation, 18 August 2010, http://tclf.org/content/newport-discoveries-rare-christopher-tunnard- garden-reappears.

11. Deborah Davis, Gilded: How Newport Became America’s Richest Resort (Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, 2009), 185.

12. Monumenta, ed. Sam Hunter (Newport, RI: Monumenta Newport Inc., 1974), 1; William Crimmins (Monumenta organizer) in discussion with the author, 10 February 2014.

13. “University Women Hear Talk.”

14. “City Architectural Treasures Priceless, Emphasizes Chorley,” The News, 26 March 1947.

15. “Newport Historic Treasures Cited,” Newport Daily News (Newport, RI), 25 April 1952.