Needlework and Their Frames

A WINTERTHUR PRIMER

- Fig. 1: Needlework, Sarah Wistar, Philadelphia, PA, 1752. Without the information inscribed on the original mount, this silkwork picture, recorded as given to the maker’s great-niece Catharine Wistar in 1789, would be anonymous. Sarah and her sister Margaret both attended the Marsh school in Philadelphia. Museum purchase (1964.120.1).

The belief that samplers were rolled up and stored so their stitches could be used as models for future projects persists despite evidence that in the eighteenth and early nineteenth century samplers and silkwork pictures were the equivalent of college diplomas (only more decorative), proudly framed and displayed on the walls of their makers’ homes as evidence of a young woman’s education. Often they were re-framed as fashions changed or the original frames were damaged.

In some cases needlework has been separated from its original mount and frame because the collector or institution focused their interest on the needlework alone. But framed needlework should be viewed as multimedia objects whose frames, backboards, glass, and particularly the original mounts (Fig. 1) can provide crucial information that can help identify and situate the large numbers of anonymous needlework merely catalogued as “English or American.” Reverse painted glass that surrounds many silkworks can often include the title of the print source, the maker, and sometimes the date of the piece, while important family genealogy is often found written on or attached to backboards (Fig. 2).1

Needlework scholar Betty Ring was interested in original frames and produced an invaluable list of looking-glass and frame makers.2 In her many publications she was careful to illustrate original frames and glass where these survived, which has enabled museums, dealers, and collectors to use them as models for new frames when the originals have been lost.

While working on an exhibition about eighteenth-century Philadelphia samplers, I noticed that while there were variations in the frames used, many examples were laced onto cedar boards through holes drilled along all four sides. For comparison, I decided to examine surviving original mounts for a number of embroidered coats of arms worked in Boston in Winterthur’s collection. I noticed that they were consistently nailed to the outside edge of a pine strainer (Fig. 3). Secondary woods on furniture, used for the backs and bottoms of drawers are routinely used by scholars to help identify the regional origin of case furniture. I believe that a study of the original mounts for samplers and silkwork pictures will help us identify the geographical origins of these often anonymous works. But this will only be possible if these parts are recognized as important and saved from destruction or separation from the needlework.

- Fig 3: Strainer for a silkwork coat of arms, possibly wrought by Hannah Hodges, Boston, Mass., 1730–1770. This detail shows the original pine strainer used to mount a coat of arms worked at a school in Boston. Inscribed “By The Name of Hodges and King,” it was probably worked by Hannah Hodges (1779–1792), daughter of Benjamin Hodges and Hannah King (1967.1393). Bequest of Henry Francis du Pont.

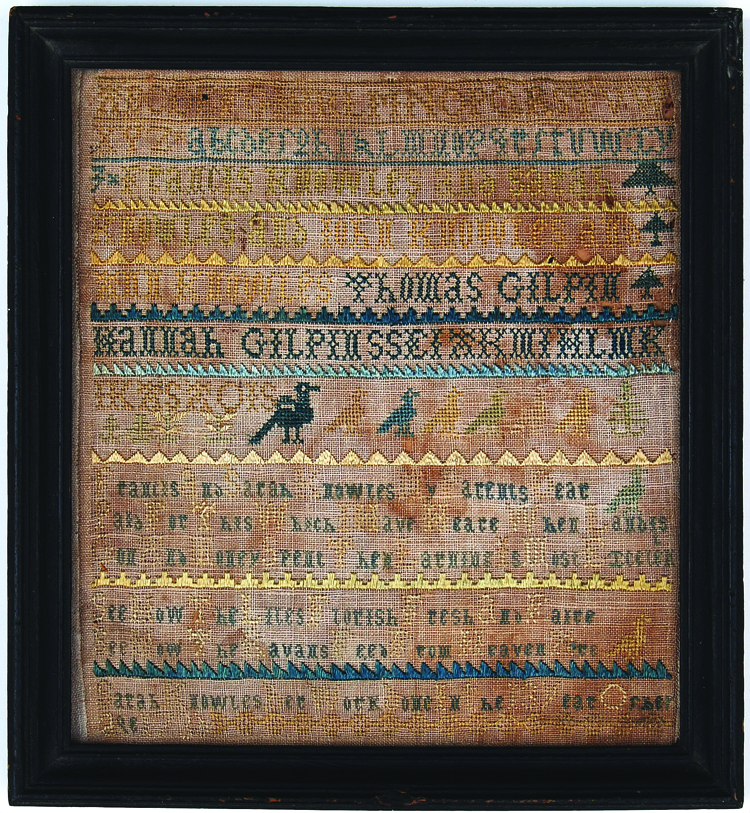

A very plain sampler worked by Philadelphian Sarah Knowles in 1736 is a good example of the significance of mounting materials (Fig. 4).3 The birds worked in cross stitch in the middle band exactly match those found on a sampler wrought by Rebecca Jones in 1750, which Betty Ring tentatively attributed to the Marsh school. Elizabeth Marsh and later her daughter Ann taught needlework from the mid 1720s through the early 1790s.4 The mounting method, however, suggests a different attribution. Instead of being laced through drilled holes like all the other examples known from the Marsh school, Sarah’s sampler was laced across the back of its original cedar mount, with four small pieces of leather adhered over the lacing at each corner to stabilize the structure (Fig. 5). This new evidence suggests that the samplers by Sarah Knowles and Rebecca Jones were worked at the school run by Rebecca’s mother, Mary Porter Jones, also in Philadelphia.5

Conservators have long been concerned that contact with wood causes damage to textiles, but examples of Philadelphia needlework with original mounts show that these were interleaved with either wool flannel (like Sarah Wistar’s birds, which are in excellent condition) or with paper. Experiments undertaken by Joy Gardiner in Winterthur’s textile conservation laboratory has shown that leaving needlework that is in good condition on its original mount will cause no further damage in the future. As a result of her work, conservators today are experimenting with ways to preserve the needlework on their original mounts. When the poor condition of the needlework precludes this option, conservators should photo-document the original mounts.

I plan to build a database about original mounts and frames and would be grateful for information and photographs of original mounts (leaton@winterthur.org).

Linda Eaton is the John L. and Marjorie P. McGraw Director of Collections and Senior Curator of Textiles at Winterthur Museum, Garden & Library.

All images courtesy Winterthur Museum, Garden & Library.

More Winterthur Primer articles are available on Incollect. Visit www.Winterthur.org for a full listing.

This article was originally published in the 14th Anniversary issue of Antiques & Fine Art magazine, a fully digitized version of which is available at www.afamag.com. AFA is affiliated with Incollect.

2. Betty Ring, “Check List of Looking-glass and Frame Makers and Merchants Known by Their Labels,” Antiques (May 1981): 1178–1195.

3. I am grateful to Amy Finkel and Jamie Banks of M. Finkel & Daughter for sharing their research on Sarah Knowles.

4. Betty Ring, Girlhood Embroidery: American Samplers & Pictorial Needlework 1650–1850 (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1993), 335.

5. Rebecca’s sampler has been removed from its original mount so the connection is made through the motifs.