New Discoveries at Historic New England’s Quincy House

During the last three years Historic New England has transformed the Quincy House, in Quincy, Massachusetts, to reflect the period around 1880, when three elderly sisters resided in the historic house. They were the last family members to live at the property before their heirs sold the house and divided up the estate for development. We chose to return the house to that period because one of the sisters, Eliza Susan Quincy, documented the furnishings in a memorandum written in 1879 and had the first floor photographed (Figs. 1, 2). Returning the house to the way it was when the Quincys were living there was a painstaking but fairly straight-forward task. What we hadn’t expected was how much more we would learn in the process about the Quincy family—particularly the women.

The house was built in 1770 by Colonel Josiah Quincy, the first of six generations of Josiah Quincys (Fig. 3). Like their neighbors the Adamses, the Quincys played important roles in the social and political life of Massachusetts. The activities of the men in the family are well known. Two were noted patriots; one was a congressman; three were Boston mayors; one was a president of Harvard; another, a journalist and fervent abolitionist; and another was assistant secretary of the U.S. Navy.

- Fig. 2: Quincy House entrance hall after reinstallation. Only about half of the family’s original furnishings remain at the house. Other pieces are from Historic New England’s collections. We were able to reproduce the wallpaper and floor covering with help from private donations and the City of Quincy’s Community Preservation Act Grants. Photography Timothy R. Tiebout.

The lives of the women are more obscure. And yet it is due in large part to Eliza Susan Quincy that we know as much as we do about her family and about the role that intelligent, articulate, and engaged Quincy women played in the political and cultural life of the region.

Eliza Susan Quincy (1798–1884)

No portrait of Eliza Susan Quincy survives, but she may be the woman seated on the right in a circa-1860 photograph (Fig. 4). Emblematic of her recording of the family’s history is her description of the front hallway in her 1879 memorandum:

The cane furniture in the Hall was brought from China 1790, by Capt. James Magee, the tenant of the house of Mr. Merchant, in Pearl Street Boston when it was bought by William Phillips for his daughter Mrs. Abigail Quincy in 1792. Mrs. Quincy on moving from Federal Street to Pearl Street purchased of Mr. Magee this furniture, also a straw carpet, also on the entry of the house, the first ever brought to Boston, & 4 drawings in Water colors, of views of Canton & its environs, drawn in China. This furniture & these drawings were removed to this house in Quincy in 1805, when the house in Pearl St. was let to Christopher Gore, where they have ever since remained.1

There are tantalizing hints in this description about real estate transactions in Boston in the early years of the Republic and about the early years of the American China Trade. (Captain Magee’s manifest from his China trader, the Astrea, survives at the Massachusetts Historical Society). Eliza Susan’s assertion that the straw matting was the first to be used in Boston suggests the excitement Bostonians felt about new merchandise purchased directly from China.

|

|

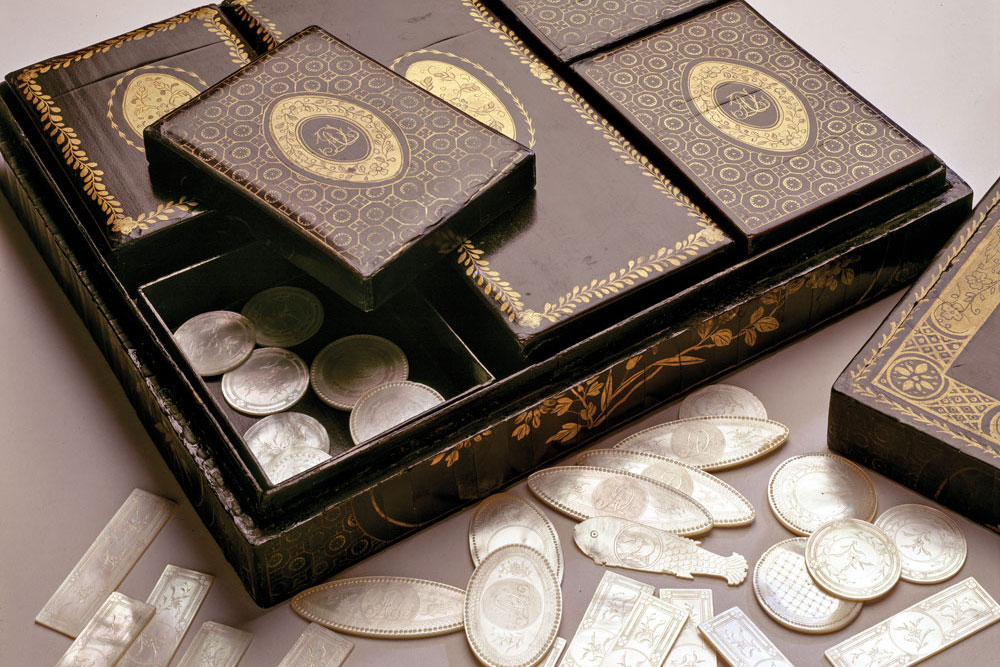

Eliza Susan’s great-uncle Major Samuel Shaw was the commercial agent aboard The Empress of China, the first American ship to reach Canton and set up direct trade relations in 1784. On his three subsequent voyages, he brought back a number of presents for his sister-in-law, Eliza Susan’s grandmother, Abigail Phillips Quincy; a game set with ivory counters with the initials A Q carved into the centers and painted on the lacquer box, and a blue and white porcelain dinner set with Abigail’s initials (Figs. 5, 6).

Because of her father’s prominent role in Boston politics, interactions with leading statesmen and cultural figures occurred throughout Eliza Susan’s life. In her diary, she describes witnessing former President Adams and then President Monroe take their leave of each other while standing in the passageway between the dining room and east parlor of the Quincy’s house in 1817 (Fig. 7). “A President of the United States taking leave, of such a distinguished predecessor, a last farewell, is a very interesting scene.” 2

She was keenly aware of the historical significance of the house in which she lived and even the room in which she slept (Fig. 8). In her mother’s memoir, which Eliza Susan edited and privately published, she wrote: “Dr. [Benjamin] Franklin passed some days with Josiah Quincy in October, 1775; and his apartment, in which these pages were written in 1860, has since been denominated in the family the Franklin Room.” 3 This may have been the room where she helped to research and edit her father’s books: Memoir of the life of Josiah Quincy, Jr., History of Harvard University¸ and Municipal History of the town and city of Boston, all three of which, according to her eulogist, President of the Massachusetts Historical Society Robert C. Winthrop, “owed not a little…to her discriminating care and judgment.” 4 This same person acknowledged that but for the bylaws preventing the admission of women, Eliza Susan Quincy would have been a distinguished member of the Massachusetts Historical Society.

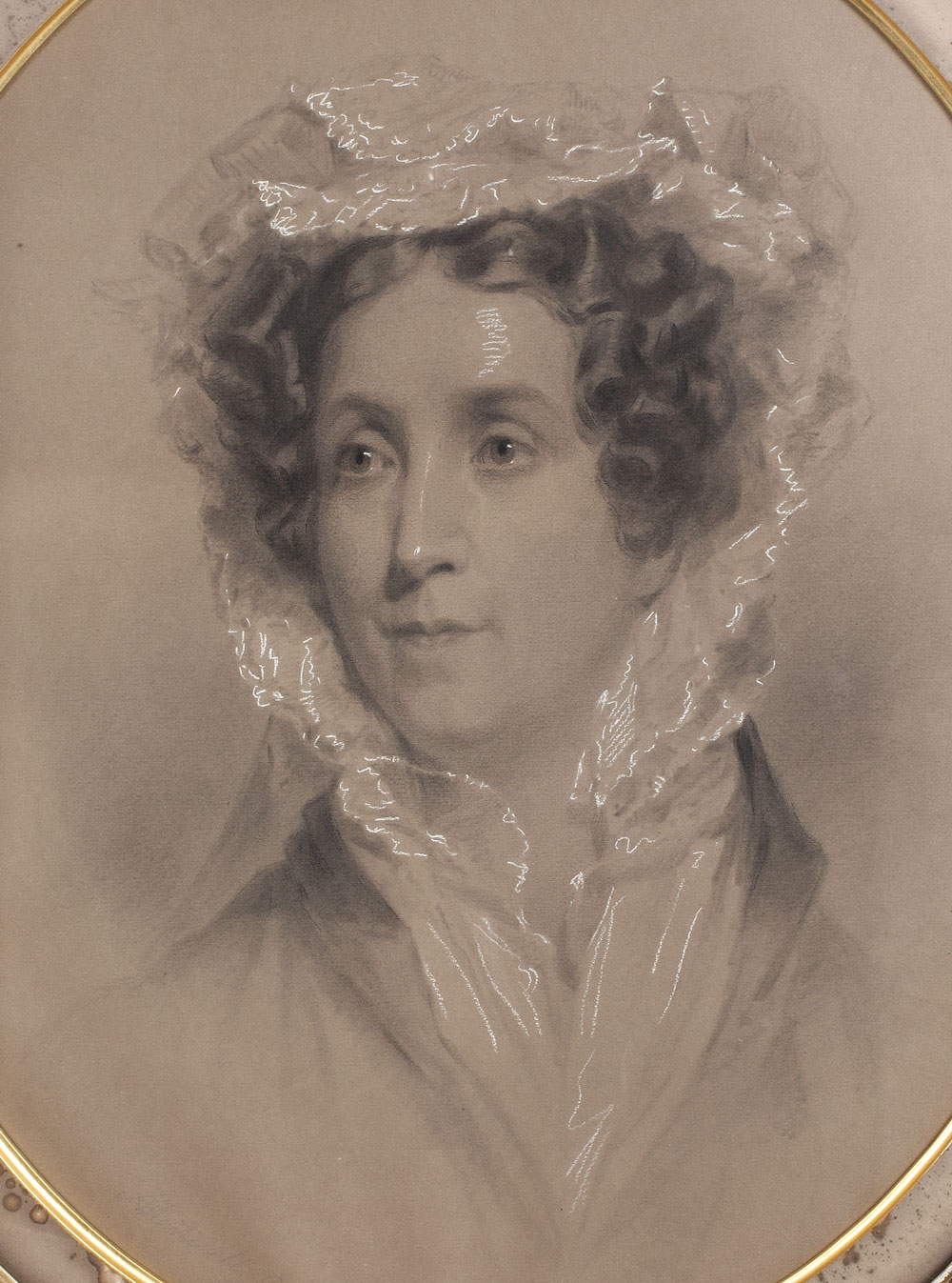

Eliza Susan Morton Quincy (1773–1850)

Eliza Susan Quincy’s mother was an anomaly, a New Yorker in a Bostonian world (Fig. 9). During her first visit to Boston, in 1795, she felt she had stepped back in time. She described attending a service at the Brattle Street Church: “The broad aisle was lined by gentlemen in the costume of the last century—in wigs, cocked hats and scarlet coats. Many peculiarities in dress, character and manners, differing from those of New York and Philadelphia, were very striking to me.” 5

When she married Josiah Quincy III in 1797, Eliza Susan Morton brought few furnishings with her from New York. One of the most poignant survivals is a badly stained print (Fig. 10), one of several that her father, a New York merchant, had imported from England in 1771. During the Revolution, the Morton family fled to New Jersey, first to Elizabethtown, and later, when that town came under threat from the British, to Basking Ridge. Among the few things they took with them was a group of prints that included this one.

Still an infant when war broke out, Eliza Susan Morton barely remembered her father, who died before the war ended.6 As one of the few items she had to remember him by, the print of the Duke of Argyle’s Seat held great significance for her.7 Another freighted object may have been the print of General Washington on the wall in her bedroom. When her family returned to New York after the Revolution, Eliza Susan Morton could recall seeing Washington disembark from his ship in New York harbor when he came to accept the Presidency. Later she watched from a nearby rooftop as he took the Oath of Office. John Adams stood close by and Harrison Gray Otis held the bible. Years later, both would become Mrs. Quincy’s friends.8

Maria Sophia Kemper Morton (1739–1832)

Perhaps the greatest surprise was the discovery that Eliza Susan’s maternal grandmother was a German immigrant who played as active a role in the American Revolution as did her contemporary Quincy relations (Fig. 11). Maria Sophia Kemper was two years old when her parents emigrated from Germany and settled in upstate New York, near Beekman. It wasn’t until she was twelve, when her family moved to New Brunswick, New Jersey, that she first heard English spoken. In New York, where the family eventually settled, Maria met a Scots-Irish soldier named John Morton. Soon after they married in 1761, Morton resigned his commission and became a successful merchant, specializing in the trade of flaxseed exported to Ireland to support that country’s linen industry. As tensions between the British and colonials grew, Morton and his family sided with the patriots. In 1775, when the British naval ship the HMS Asia trained her guns on the city and threatened to fire, Morton loaded one of his vessels with as much from his warehouses as it could carry and sailed it to Philadelphia. He sold the contents and took the money to the Continental Congress, saying that while he was too old to serve, and his sons too young, “he would pay those who could, to the last farthing he possessed.” 9

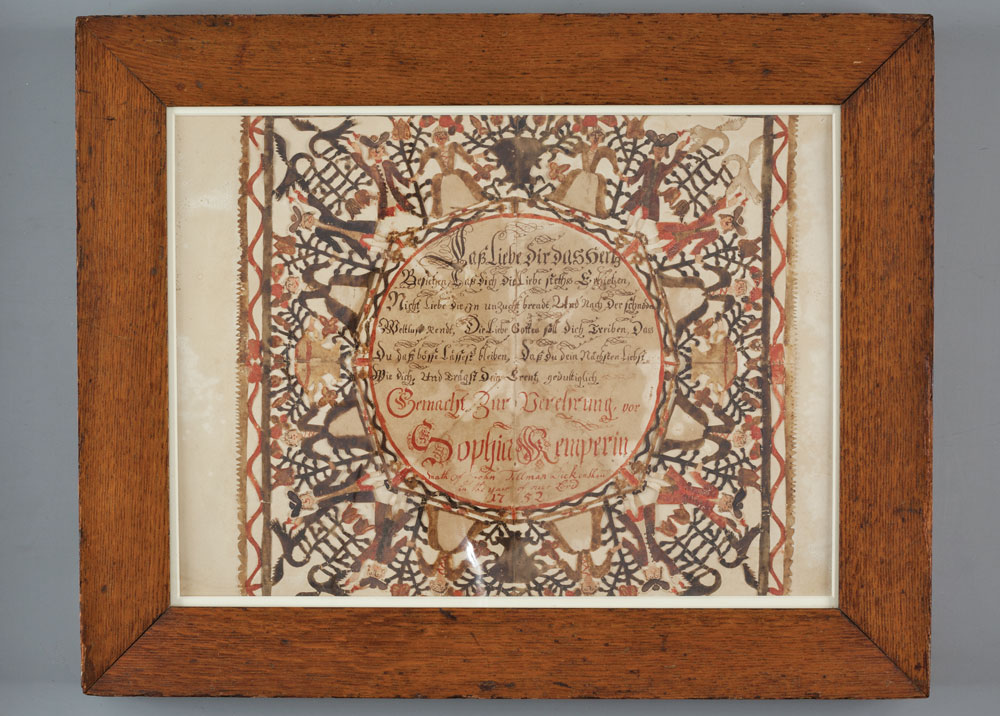

From their exile in Basking Ridge, Maria and her husband supported Washington’s troops in the nearby encampment in Morristown, establishing an army hospital on their land and providing housing for the medical staff. On occasion Washington and members of his staff dined with the Mortons. John Morton died in Basking Ridge in 1781. After the war Maria Morton returned with her family to New York and later moved to Boston to live with her daughter’s family, where, although a strict Calvinist, she “willingly attend[ed] the Unitarian church in Cambridge.” 10 After her death, at age ninety-three, her family discovered a paper squirreled away in what Eliza Susan Quincy described as “the till of her chest.” 11 By this time, 1832, few New Englanders of means were using seventeenth-century chests with tills. It seems likely instead that Maria Morton’s chest was made in the German tradition. The paper, also in the German tradition, was a cut-paper valentine, dated 1752, and inscribed to Maria Sophia Kemper (Fig. 12), likely a tribute from a young German suitor.

When Eliza Susan Quincy’s youngest sister Anna Quincy Waterston traveled with her husband and daughter in 1857 to the village in Germany where her grandmother was born, she wrote back to her sister: “How strangely are all our destinies linked in with those of other days—long, long passed away.” 12

The Quincy House, at 20 Muirhead Street, Quincy, Massachusetts, is open to the public on the first and third Saturdays of the month between June 1 and October 15. For more information call 617.227.3956 or visit www.historicnewengland.org.

-----

Nancy Carlisle is the senior curator of collections at Historic New England.

This article was originally published in the Autumn 2016 issue of Antiques & Fine Art magazine, a fully digitized version of which is available at afamag.com. AFA is affiliated with Incollect.

2. In M. A. DeWolf Howe, ed., The Articulate Sisters (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1946), 22.

3. Memoir of the Life of Eliza S. M. Quincy (Boston: J. Wilson and Son,1861), 92n.

4. “Tribute to Miss Eliza Susan Quincy,” Proceedings of the Massachusetts Historical Society (February, 1884): 33.

5. Ibid, 61.

6. Letter, Eliza Susan Morton Quincy to P. W. Gallaudet, Jan. 7, 1841, in Memoir of the Life of Eliza S. M. Quincy, 261–262.

7. Eliza Susan Quincy, “Memorandum”, 35.

8. Memoir, 50-51.

9. Memoir, 17.

10. Memoir, 224.

11. “Memorandum”, 8.

12. Letter, Mrs. Anna C. L. Q. Waterston to Miss [Eliza Susan] Quincy, July 7, 1857, in Memoir, 267.