New Discoveries Concerning the Bold Art of John Haley Bellamy

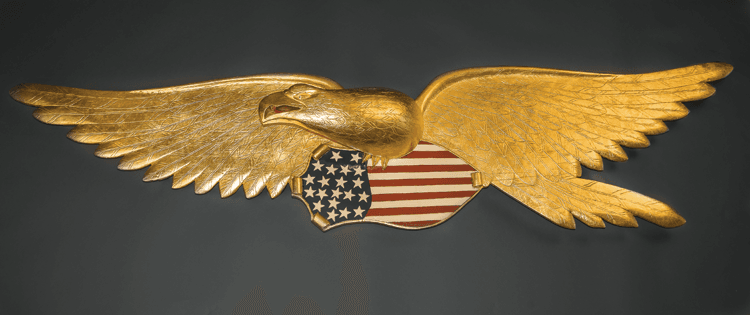

American Eagle

The simple, austere lines and curves that convey the unmistakable sense of steadfast swiftness and strength of a Bellamy eagle—with wings outstretched, often clutching a shield or flags, and brandishing banners—evoke the character and ideals of the American nation in a way no artist prior to its creator, John Haley Bellamy (1836–1914), had envisioned (Fig 1). Not since the 1982 publication of lay historian Yvonne B. Smith’s John Haley Bellamy, Carver of Eagles, has this popular carver’s life and work been examined. This has now changed with the retrospective exhibition and accompanying publication, American Eagle: The Bold Art and Brash Life of John Haley Bellamy, which examines the career of this celebrated American woodcarver in depth.

Hitherto overlooked aspects of his career, involving his crafting of furniture, Masonic-themed carvings, mechanical inventions, and works of pure whimsy present a broader picture of the man, revealing him to have been an infinitely more diverse and talented artist than previously described. Depicted alternately as a disciplined laborer and a helpless drunkard, a manic inventor and an aloof poet, an irresponsible pleasure-seeker and a devoted kinsman, Bellamy’s true life’s story has been obscured by a smokescreen of ribald legends and tall tales (Fig. 2).

The son of a housewright, boat builder, and inspector of timber, Bellamy was born in the seaside community of Kittery, Maine. Through the example of his ambitious father, Charles Gerrish Bellamy, he gained his first exposure to the woodcarver’s vocation. When the time arrived to leave home, John Haley Bellamy apprenticed to an established woodcarver. Despite older claims that Boston woodcarver Laban S. Beecher was his master, Bellamy was actually trained by Samuel Dockum in neighboring Portsmouth, New Hampshire. Dockum was a house and ship carver, who made everything from coffins to rocking chairs to the finish work on many Piscataqua River-built clipper ships. Bellamy’s apprenticeship likely lasted six years; beginning sometime after 1851, when he began working for Dockum at the age of fifteen, to 1857.

- Fig. 4: John Haley Bellamy (1836–1914), Sternboard of Unidentified US Naval Vessel, ca. 1860–1900. Painted pine, H. 17, W. 125½, D. 5¼ in. Collection of Paul DeCoste. Another previously undocumented creation hailing from Bellamy’s naval carving career, this device may have decorated the stern of an American sloop-of-war.

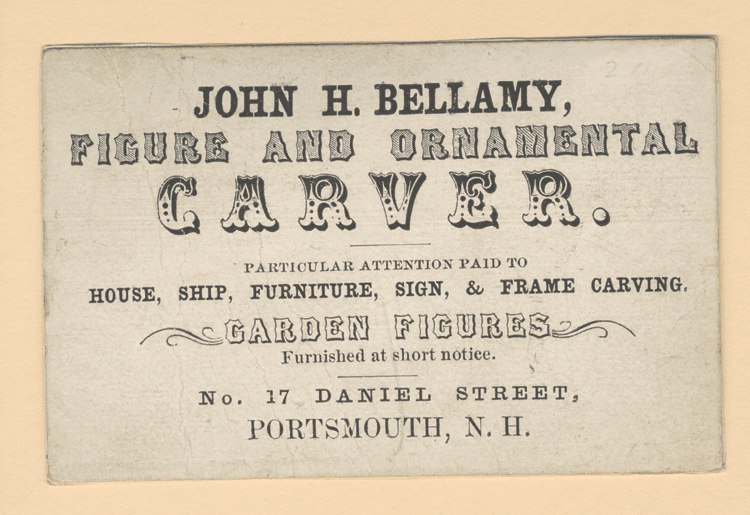

Bellamy launched his woodcarving career in 1859 by establishing a studio at 17 Daniel Street in Portsmouth, in rooms he likely rented from Dockum. His business card advertises a master woodcarver capable of executing the full array of jobs incumbent upon American woodcarvers at that time (Fig. 3). An 1859 newspaper informs us that he was making ship’s figureheads for the shipbuilders of Portsmouth. After brief stints spent in the shipyards of East Boston and Medford, Massachusetts, the epicenter of mid-nineteenth-century shipbuilding in New England, by 1860, Bellamy had left his commercial clientele behind to work as a decorative shipcarver for the United States Navy. Working first at the Portsmouth Navy Yard, then at the Charlestown, Massachusetts, Navy Yard, Bellamy began an association with the navy that lasted as late as circa 1898–1900.

Previously unknown creations recently discovered reveal that from catheads and billetheads to stern boards and figureheads, no facet of a warship’s exterior that could accommodate decorative woodcarving was beyond the reach of Bellamy’s hand (Figs. 4). A particular specialty appears to have been gangway boards: large decorative plaques that lined the sides of a ship’s gangway (Fig. 5).

His most celebrated creation was the USS Lancaster eagle figurehead (Fig. 6). Conceived and carved between December 1879 and August 1881, the majestic eagle is Bellamy’s magnum opus. It is as much a feat of engineering as a work of art, given the challenges of holding intact this three-thousand-pound gilded pine carving with an eighteen-foot wingspan atop the bow of a warship subjected to the unforgiving oceanic environment for over twenty years.

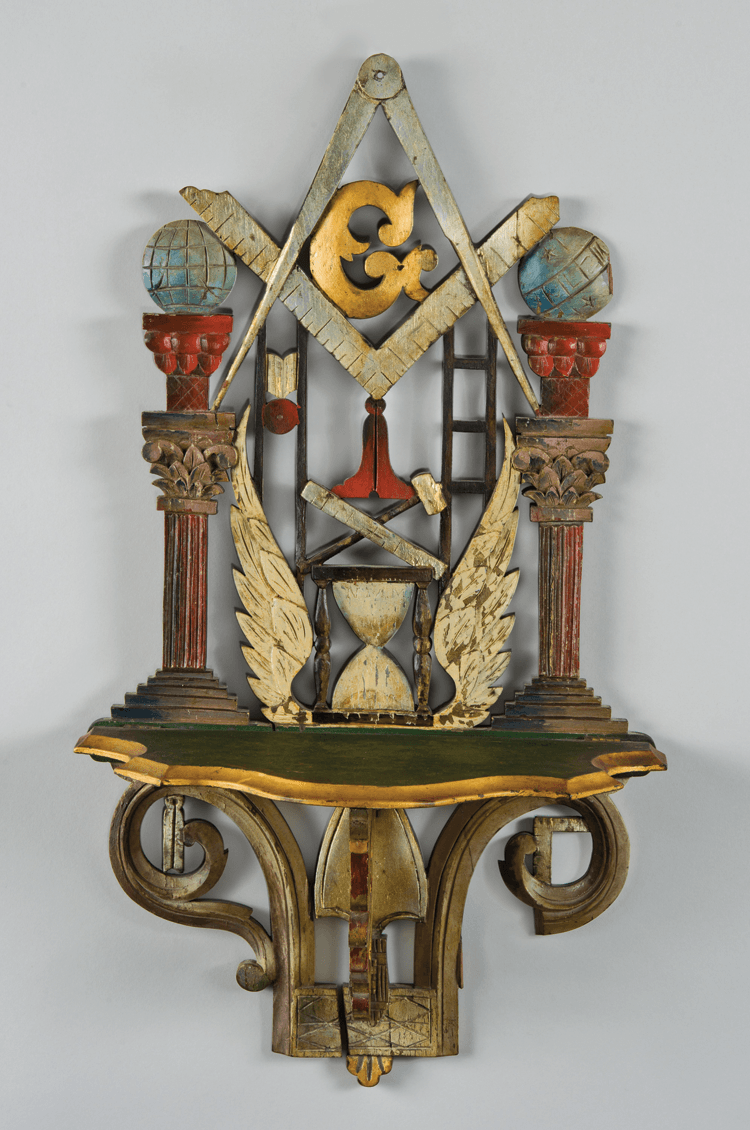

- Fig. 7: Titcomb & Bellamy, painted Masonic what-not shelf, ca. 1866–72. Painted walnut, H. 22, W. 12, D. 6½ in. Private collection. Courtesy, Allan Katz Americana. Photography by Gavin Ashworth. To date this newly uncovered what-not shelf is the only piece of its kind known to have a complete paint treatment contemporary to the time of its creation. It may have been painted for display in the window of the Titcomb & Bellamy shop.

Due to long bouts of unemployment between projects in the post-Civil War navy yard, Bellamy partnered with a fellow navy-yard worker in July of 1866 to form Titcomb & Bellamy, “Makers of Emblematic Frames and Brackets.” Located at 11 City Square, Charlestown, Massachusetts, on the first floor of a Masonic lodge, the firm sought to cash in on a post-Civil War resurgence of membership in fraternal organizations (particularly Freemasonry). Bellamy designed and produced a wide array of frames, clock cases, and what-not shelves replete with the symbols of Freemasonry (Fig. 7). His partner, David A. Titcomb, sold them to a dozen states stretching from Vermont to Florida, and as far west as Mississippi.

Personal letters to and from Bellamy reveal he employed apprentices in his Charlestown studio, and in times of high demand, even his father and younger brother Elisha (himself a master woodcarver), in the production of these designs. Close investigation reveals that they were mass-produced, constructed by use of nascent assembly line methods, using mechanical scroll saws and patterns to ensure uniformity of design and rapid production.

Bellamy had sold his interest in Titcomb & Bellamy and returned to the Piscataqua region by September of 1872. With the experiences gained from running his fast-paced, profitable workshop and recognizing the economic opportunity of the region’s blossoming tourism industry, Bellamy embarked in a new direction. The patriotic American eagle promised him a wider audience and greater sales than his fraternal carvings ever could.

Bellamy’s first eagle carving commissions were for large eagles in the round or long, wide forms for commercial and civic clients. Placed conspicuously in areas of high traffic, these eagles provided Bellamy with an income and popularized another type of eagle carving he had conceived in Charlestown. Known today as the “Bellamy eagle,” these two-foot-wide painted plaques are among the most celebrated and instantly recognizable pieces of Americana (Fig. 8).

Easily transportable, affordably priced (only one or two dollars apiece), and sporting any number of political, fraternal, religious, holiday, and personal sentiments, from “Don’t Give Up the Ship,” to “Merry Christmas!” (Fig. 9). The Bellamy eagle easily appealed to a wide and diverse clientele.

Like his Masonic-themed carvings in Charlestown, Bellamy employed nascent assembly line production methods for optimum mass-production—reducing details, streamlining, and deconstructing the eagles down to their most basic components. In crafting these birds, Bellamy harkened toward the minimalism found in the coming century’s works of modern art. Consisting of four pieces held together with a minimum of hardware, they were easy to craft and his shop was able to fill orders ranging from five to seven hundred at a time for local patrons like Portsmouth brewer Frank Jones, and those further afield, like the Manhattan Storage & Warehouse Company of New York City. Once again he hired his father, brother Elisha, and probably his younger brother, Charles Jr., to help with the volume of eagle carvings produced from 1872 to the early years of the twentieth century.

Yet even while producing some of his more elaborate eagle plaques (Fig. 10), Bellamy also toiled as a house carpenter, fashioning interior and exterior decorative carvings for Portsmouth and Kittery homes. He also carved furniture and works of pure whimsy.

In his day, John Haley Bellamy was a literate poet and urbane raconteur who enjoyed close personal friendships with many of the leading writers and artists of his day, including Winslow Homer, William Dean Howells, and the incomparable Mark Twain. The last of his nine siblings to pass away, his hands gnarled with arthritis, his mind deteriorating with age, in February 1911, Bellamy was deemed legally incompetent and forced to reside with a cousin in Portsmouth; he died from a stroke on April 5, 1914.

Nowadays, carvings that Bellamy charged one dollar for easily fetch as much as $160,000 at auction, and larger pieces have sold for $660,000. His was an artistic vision that has defied changing temperaments and fashions. To gaze into the fierce eye of a Bellamy eagle is to look into the very soul of the American nation.

The exhibition Bold & Brash: The Art of John Haley Bellamy, is on view at the Portsmouth Historical Society’s Discover Portsmouth Center, New Hampshire, through October 3, 2014 (www.PortsmouthHistory.org); an exhibition catalogue is available. On display are more than one hundred Bellamy carvings and numerous artifacts—from his earliest known drawings executed in childhood to his final creation fashioned in 1912—drawn from nearly forty public and private collections and many not publicly exhibited since Bellamy’s time.

James A. Craig (www.jamesacraig.com) is the author of American Eagle: The Bold Art and Brash Life of John Haley Bellamy and curator of Bold & Brash, the Art of John Haley Bellamy.

Coastal Copyists and Inspired Imitators: the Art of Bootlegging Bellamy

Given the financial success John Haley Bellamy reaped with his widely popular eagle carvings, it was inevitable that other Portsmouth-area woodcarvers should take up their tools and craft their own facsimiles of the Bellamy eagle. In a tribute to the Bellamy eagle’s enduring appeal, this tradition of copy work continued well into the mid-twentieth century. Here are the most prominent.

No. 1

Ivah W. Spinney (1881–1963)

A native of Portsmouth, New Hampshire, Ivah W. Spinney appears to have begun actively carving in the waning years of Bellamy’s career. Spinney’s creations demonstrate an obvious debt of influence to Bellamy’s eagles. Spinney owned at least one Bellamy eagle, now in the collection of the Portsmouth Athenaeum, which inspired some of his own carvings.

No. 2

Captain Edward H. Adams (1860–1951) and E. Cass Adams (1892–1959)

Residents of Adams Point in nearby Durham, New Hampshire, this father and son team whittled a wide assortment of carvings, including adept copies of the classic Bellamy eagle. Derived from an in-depth study of Bellamy’s handiwork, Edward Adams hand carved his eagles; his son Cass applied the paint that brought them to life.

No. 3

Walter Ketzler (1893–1986)

An immigrant from Barmen, Germany, Walter Ketzler arrived in New York in 1922 to work as a sign and interior painter in Brooklyn. By 1955, he was working in Portsmouth, living with his wife and son in Eliot, Maine. A skilled professional decorator and cabinetmaker, Ketzler is known to have carved his inspired copies of the Bellamy eagle as a gift for clients, and even went so far as to teach others in his method of copying Bellamy’s handiwork.

No. 4

Artistic Carving Co. of Boston

While an older Artistic Carving Company provided architectural carvings in Boston in the 1890s, the manufacturer of mid-century eagles seems to have begun in 1923. John Seibert and Arthur L. Wertz were the owners of this 21 Wareham St. business. Following the Second World War, a surge in national patriotism led the Artistic Carving Company to churn out a wide assortment of reproductions of nineteenth-century American eagle carvings, including some designs original to Bellamy himself. Manufactured in a purely industrial environment, these carvings have deceived many an untutored eye, leading them to believe that they were actual Bellamy creations.

No. 5

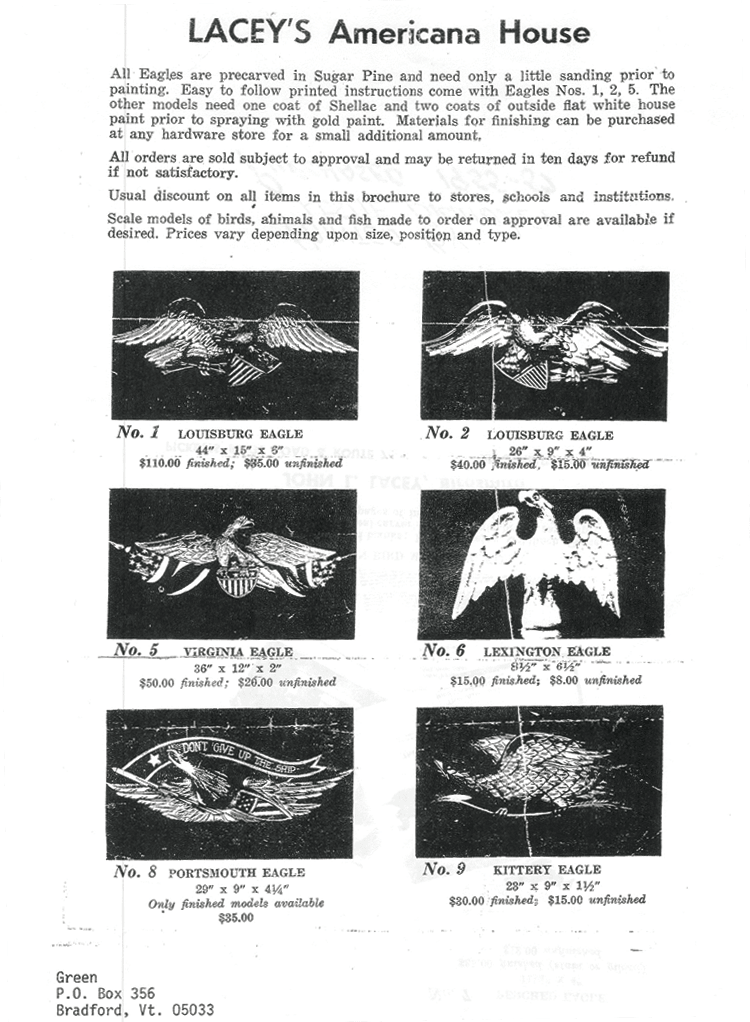

Lacey’s Americana House

Located in Ridgefield, Connecticut, in the 1950s. Lacey’s Americana House offered a wide assortment of eagles rendered in a number of patriotic poses little different from those of the Artistic Carving Company. Machine cut from boards of sugar pine and sold to the public in an unpainted, unvarnished state, two of these kits have undoubtedly caused much confusion for untutored Bellamy collectors. Fittingly titled the “Portsmouth Eagle” and “Kittery Eagle,” these two models further illustrate how enterprising companies eagerly produced facsimiles of Bellamy’s handiwork.

This article was originally published in the Autumn 2014 issue of Antiques & Fine Art magazine, a digitized version of which is available at afamag.com. InCollect.com is a division of Antiques & Fine Art, AFAnews, and AFA Publishing.

![Fig. 8: John Haley Bellamy (1836–1914), “Health to the Navey!” [sic] eagle, ca. 1872–1900. Painted pine, 9 x 26 in. Private collection. Photo by Ralph Morang Photography.](../sites/uploads/fig0083.png)